Musculoskeletal System - Limb Development

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Introduction

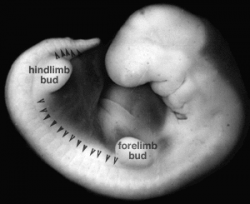

The early "limb bud" consists of a simple ectoderm cover with a mesoderm core that vascularises and both somite mesoderm and nerves invade. Generally the upper limb develops before the lower limb, and in the case of birds and bats then develops as a wing. Externally the structure of the limb is established by the end of the embryonic period (week 8), except for nails and hair. Internally limb tissue differentiation (bone, muscle) continues through the fetal period and into postnatal development.

Limb development has been studied in the embryo extensively as a model for how limb pattern formation, limb axis, is established. For example, in the chicken the early limb bud was modified and transplanted to identify key signalling regions. Then beads coated with specific factors were used and finally genetic modification of animal models. Note that pattern formation signals differ from those required for overt tissue differentiation.

The mesoderm forms nearly all the connective tissues of the musculoskeletal system. Each tissue (cartilage, bone, and muscle) goes through many different mechanisms of differentiation. The musculoskeletal system consists of skeletal muscle, bone, and cartilage and is mainly mesoderm in origin with some neural crest contribution.

Somites appear bilaterally as pairs at the same time and form earliest at the cranial (rostral,brain) end of the neural groove and add sequentially at the caudal end. This addition occurs so regularly that embryos are staged according to the number of somites that are present. Different regions of the somite differentiate into dermomyotome (dermal and muscle component) and sclerotome (forms vertebral column). An example of a specialized musculoskeletal structure can be seen in the development of the limbs.

Skeletal muscle forms by fusion of mononucleated myoblasts to form mutinucleated myotubes. Bone is formed through a lengthy process involving ossification of a cartilage formed from mesenchyme. Two main forms of ossification occur in different bones, intramembranous (eg skull) and endochondrial (eg limb long bones) ossification. Ossification continues postnatally, through puberty until mid 20s. Early ossification occurs at the ends of long bones.

Musculoskeletal abnormalities and limb abnormalities are one of the largest groups of congenital abnormalities.

Development of the other parts of the appendicular skeleton, shoulder and pelvis, are described on separate pages.

| Musculoskeletal Links: Introduction | mesoderm | somitogenesis | limb | cartilage | bone | bone timeline | bone marrow | shoulder | pelvis | axial skeleton | skull | joint | skeletal muscle | muscle timeline | tendon | diaphragm | Lecture - Musculoskeletal | Lecture Movie | musculoskeletal abnormalities | limb abnormalities | developmental hip dysplasia | cartilage histology | bone histology | Skeletal Muscle Histology | Category:Musculoskeletal | ||

|

| Factor Links: AMH | hCG | BMP | sonic hedgehog | bHLH | HOX | FGF | FOX | Hippo | LIM | Nanog | NGF | Nodal | Notch | PAX | retinoic acid | SIX | Slit2/Robo1 | SOX | TBX | TGF-beta | VEGF | WNT | Category:Molecular |

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Limb Embryology | Limb Development | Limb Axis Development |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

Textbooks

Moore, K.L., Persaud, T.V.N. & Torchia, M.G. (2015). The developing human: clinically oriented embryology (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders.

| ||||

|

Schoenwolf, G.C., Bleyl, S.B., Brauer, P.R., Francis-West, P.H. & Philippa H. (2015). Larsen's human embryology (5th ed.). New York; Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

|

Objectives

- Identify the components of a somite and the adult derivatives of each component.

- Give examples of sites of (a) endochondral and (b) intramembranous ossification and to compare these two processes.

- Identify the general times (a) of formation of primary and (b) of formation of secondary ossification centres, and (c) of fusion of such centres with each other.

- Briefly summarise the development of the limbs.

- Describe the developmental abnormalities responsible for the following malformations: selected growth plate disorders; congenital dislocation of the hip; scoliosis; arthrogryposis; and limb reduction deformities.

Development Overview

Below is a very brief overview using simple figures of 3 aspects of early musculoskeletal development. More detailed overviews are shown on other notes pages Mesoderm and Somite, Vertebral Column, Limb in combination with serial sections and Carnegie images.

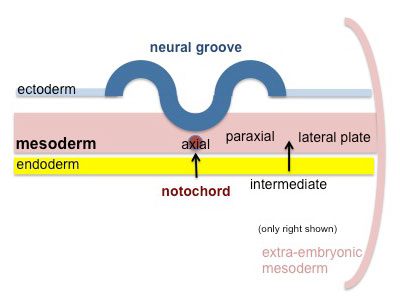

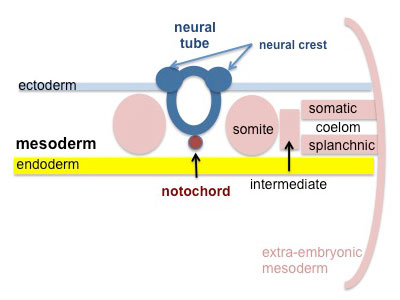

Mesoderm Development

|

Cells migrate through the primitive streak to form mesodermal layer. Extraembryonic mesoderm lies adjacent to the trilaminar embryo totally enclosing the amnion, yolk sac and forming the connecting stalk. |

|

Paraxial mesoderm accumulates under the neural plate with thinner mesoderm laterally. This forms 2 thickened streaks running the length of the embryonic disc along the rostrocaudal axis. In humans, during the 3rd week, this mesoderm begins to segment. The neural plate folds to form a neural groove and folds. |

|

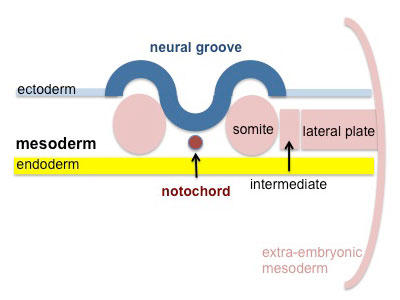

Segmentation of the paraxial mesoderm into somites continues caudally at 1 somite/90minutes and a cavity (intraembryonic coelom) forms in the lateral plate mesoderm separating somatic and splanchnic mesoderm.

Note intraembryonic coelomic cavity communicates with extraembryonic coelom through portals (holes) initially on lateral margin of embryonic disc. |

|

Somites continue to form. The neural groove fuses dorsally to form a tube at the level of the 4th somite and "zips up cranially and caudally and the neural crest migrates into the mesoderm. |

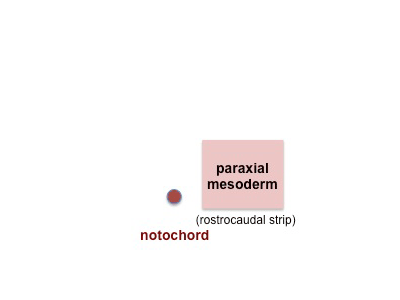

Somite Development

|

Mesoderm beside the notochord (axial mesoderm, blue) thickens, forming the paraxial mesoderm as a pair of strips along the rostro-caudal axis. |

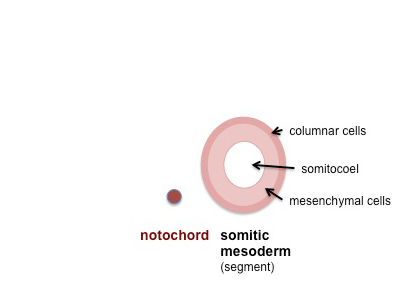

|

Paraxial mesoderm towards the rostral end, begins to segment forming the first somite. Somites are then sequentially added caudally. The somitocoel, is a cavity forming in early somites, which is lost as the somite matures. |

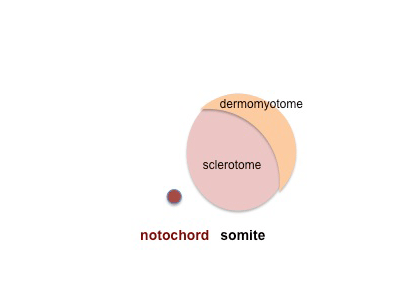

|

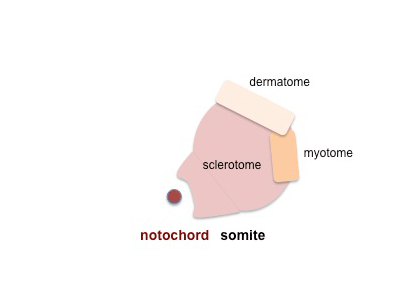

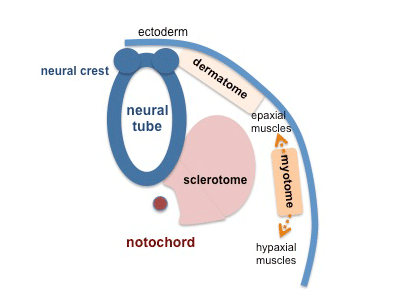

Cells in the somite differentiate medially to form the sclerotome (forms vertebral column) and dorsolaterally to form the dermomyotome. |

|

The dermomyotome then forms the dermotome (forms dermis) and myotome (forms muscle).

Neural crest cells migrate beside and through somite. |

|

The myotome differentiates to form 2 components dorsally the epimere and ventrally the hypomere, which in turn form epaxial and hypaxial muscles respectively. The bulk of the trunk and limb muscle coming from the Hypaxial mesoderm. Different structures will be contributed depending upon the somite level.

Limb skeletal muscle arises from the hypomere region of the myotomes adjacent to the developing upper (C5-C8) and lower (L3-L5) limb buds. |

Limb Axis Formation

Four Concepts - much of the work has been carried out using the chicken and more recently the mouse model of development.

- Limb Initiation

- Proximodistal Axis

- Dorsoventral Axis

- Anteroposterior Axis

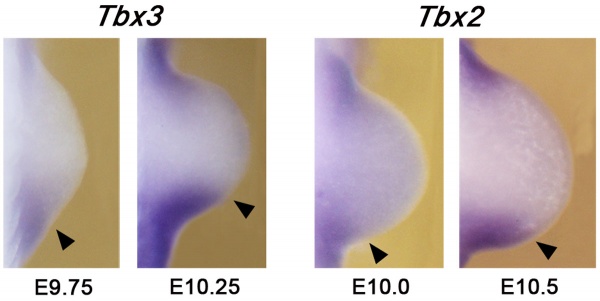

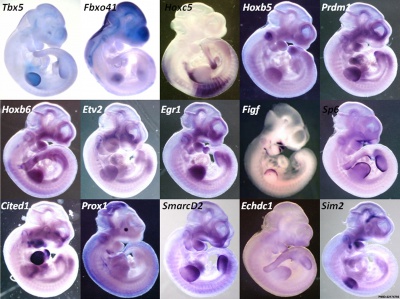

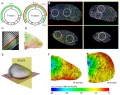

Mouse limb Patterning Images

- Mouse Limb Images: Tbx3 and Tbx2 forelimb E10 | Alx3 and Gli3 forelimb E10 | Fgf and Hox forelimb E10.5 | Bmp4 forelimb E11.5 | Bmp4 hindlimb E11.5 | Shh forelimb E11.5 | Fgf8 hindlimb E11.5 | Sox9 forelimb E12.5 | Msx2 forelimb E12.5 | Shh hindlimb E12.5

- Links: Fgf | Hox | Shh | Sox | Limb Development | Mouse Development

| More about Axis Development | |

|---|---|

The following links are to more general information about whole body axis development and anatomical planes.

|

Limb Initiation

- Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) coated beads can induce additional limb

- FGF10 , FGF8 (lateral plate intermediate mesoderm) prior to bud formation

- FGF8 (limb ectoderm) FGFR2

- FGF can respecify Hox gene expression (Hox9- limb position)

- Hox could then activate FGF expression

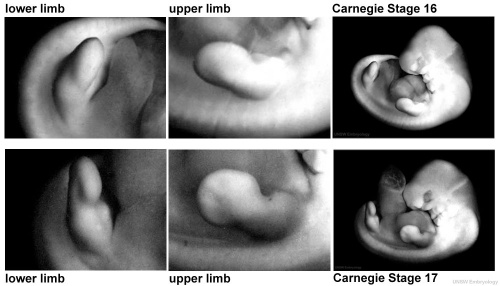

Note that during the embryonic period there is a rostrocaudal (anterior posterior) timing difference between the upper and lower limb development

- this means that developmental changes in the upper limb can precede similar changes in the lower limb (2-5 day difference in timing)

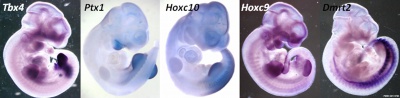

Limb Identity

Forelimb and hindlimb (mouse) identity appears to be regulated by T-box (Tbx) genes, which are a family of transcription factors.

- hindlimb Tbx4 is expressed.

- forelimb Tbx5 is expressed.

- Tbx2 and Tbx3 are expressed in both limbs.

Related Research - [22] | Development 2003 Figures | Scanning electron micrographs of E9 Limb bud wild-type and Tbx5del/del A model for early stages of limb bud growth | PMID: 12736217 | Development 2003 Figures

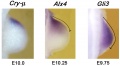

Tbx3 and Tbx2 expression in E9.75 to 10.5 wild-type mouse embryonic forelimb.[19]

Body Axes

- Anteroposterior - (Rostrocaudal, Craniocaudal, Cephalocaudal) from the head end to opposite end of body or tail.

- Dorsoventral - from the spinal column (back) to belly (front).

- Proximodistal - from the tip of an appendage (distal) to where it joins the body (proximal).

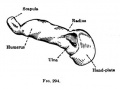

Proximodistal Axis

- Apical Ectodermal Ridge (AER) formed by Wnt7a

- then AER secretes FGF2, 4, 8

- stimulates proliferation and outgrowth

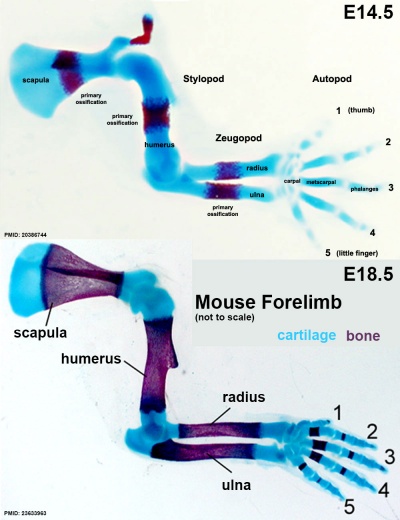

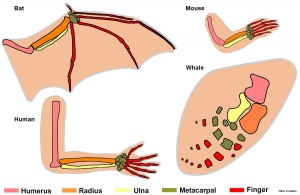

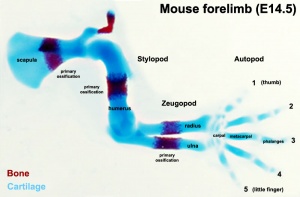

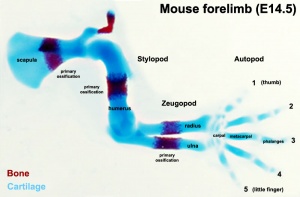

The developing limb can be described along the proximodistal axis as having three main regions:

- Stylopod - the proximal region the limb, the skeletal component of the upper limb (forelimb) is the humerus, and for the lower limb (hindlimb) is the femur.

- Zeugopod - the mid-section of the limb , the skeletal components of the upper limb (forelimb) are the radius and ulna, and for the lower limb (hindlimb) are the tibia and fibula.

- Autopod - the distal region the limb, the musculoskeletal component of the upper limb (forelimb) is the hands, and for the lower limb (hindlimb) is the foot.

Dorsoventral Axis

- Somites - provides dorsal signal to mesenchyme which dorsalizes ectoderm

- Ectoderm - then in turn signals back (Wnt7a) to mesenchyme to pattern limb

Wnt7a

- name was derived from 'wingless' and 'int’

- Wnt gene first defined as a protooncogene, int1

- Humans have at least 4 Wnt genes

- Wnt7a gene is at 3p25 encoding a 349aa secreted glycoprotein

- patterning switch with different roles in different tissues

- mechanism of Wnt and receptor distribution still being determined (free diffusion, restricted diffusion and active transport)

One WNT receptor is Frizzled (FZD)

- Frizzled gene family encodes a 7 transmembrane receptor

Fibroblast growth factors (FGF)

- Family of at least 17 secreted proteins

- bind membrane tyrosine kinase receptors

- Patterning switch with many different roles in different tissues

- FGF8 = androgen-induced growth factor, AIGF

FGF receptors

- comprise a family of at least 4 related but individually distinct tyrosine kinase receptors (FGFR1- 4) similar protein structure

- 3 immunoglobulin-like domains in extracellular region

- single membrane spanning segment

- cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain

Anteroposterior Axis

- Zone of polarizing activity (ZPA)

- a mesenchymal posterior region of limb

- secretes sonic hedgehog (SHH)

- note digit 1 (thumb/big toe) is the only digit that forms independent of SHH activity.

- apical ectodermal ridge (AER), which has a role in patterning the structures that form within the limb

- majority of cell division (mitosis) occurs just deep to AER in a region known as the progress zone

- A second region at the base of the limbbud beside the body, the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) has a similar patterning role to the AER, but in determining another axis of the limb

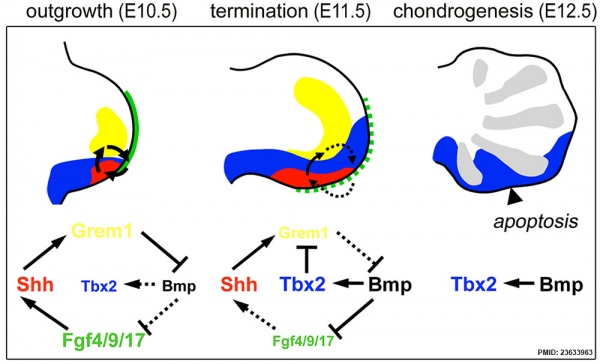

Hindlimb Tbx2 model[24]

- HAND2 - upstream of SHH controls expression of genes in the proximal limb bud.[25]

- anterior/posterior polarity of limb bud mesenchyme (affecting Gli3 and Tbx3 expression).

- TBX3 - required downstream of HAND2 to refine posterior Gli3 expression boundary.

Week 5

|

|

|

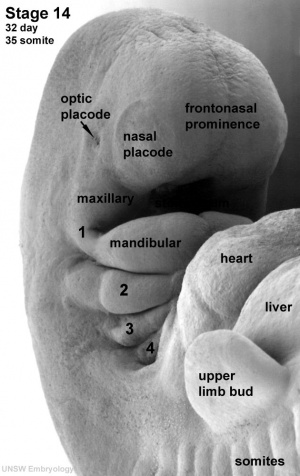

| Carnegie stage 13 | Carnegie stage 14 | Carnegie stage 15 |

|

- Links: Week 5 | Carnegie stage 13 | Carnegie stage 14 | Carnegie stage 15

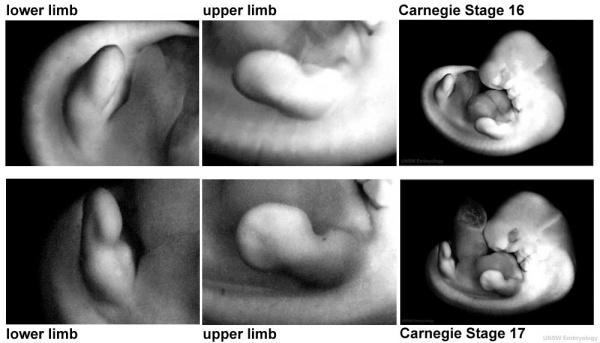

Week 6

Digital rays become visible on the upper limb.

- Links: Week 6 | Carnegie stage 16 | Carnegie stage 17

Week 7

|

|

| Carnegie stage 18 | Carnegie stage 19 |

Digital rays become visible on the lower limb.

- Links: Week 7 | Carnegie stage 18 | Carnegie stage 19

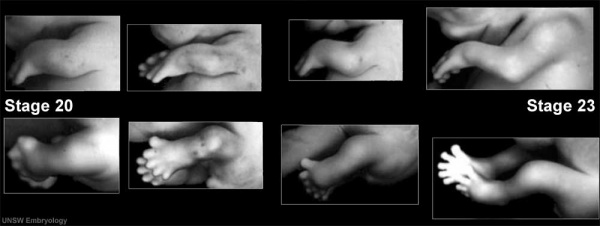

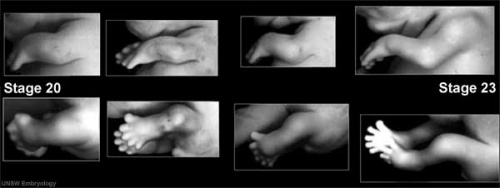

Week 8

- Links: Week 8 | Carnegie stage 20 | Carnegie stage 21 | Carnegie stage 22 | Carnegie stage 23

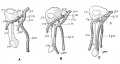

Limb Rotation

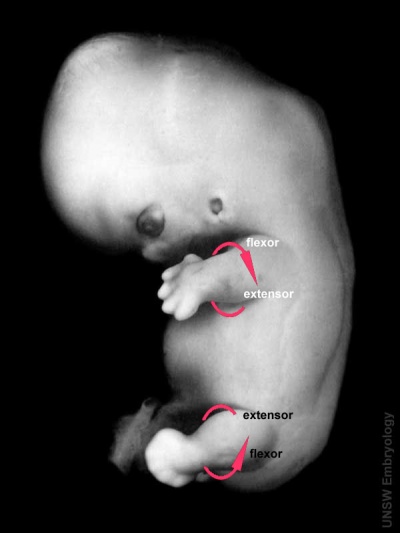

Human Embryo (Carnegie stage 19) showing direction of limb rotation. |

| |||||||||||||||||

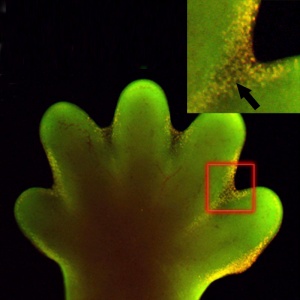

Interdigital Apoptosis

Early development of both the hand and foot appear initially as "paddles" at the end of the upper and lower limb respectively. As they continue to grow the digits (fingers and toes) are initially "webbed" together and the cells in the webbing die by programmed cell death to form the separate digits, this process is described as interdigital apoptosis.

Interdigital apoptosis, like general limb growth, occurs first in the upper limb and then later in the lower limb.

- Links: apoptosis

Fetal Growth

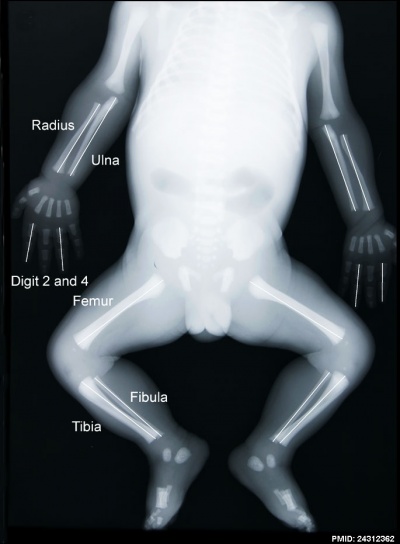

Fetal limb X-ray[26] |

Embryonic period - the external appearance of both the upper and lower limb has been formed.

Play the associated animation to observe the relative change in limb dimensions.

|

Limb Vessels

Lower Limb

These figures by Senior are from an historic 1919 study.[27]

- Lower Limb (1919)

| Carnegie Embryos - Senior (1919) - Lower Limb Blood Vessels | ||

|---|---|---|

| Embryo CRL | Collection | Catalogue No. |

| 6.0 mm+ | Carnegie Institution, Embryological Collection (C.T.E.C.) | 1075 |

| 8.5 mm+ | Cornell University, Embryological Collection (C.E.C.) | 9 |

| 12.0 mm+ | Cornell University, Embryological Collection (C.E.C.) | No. 3. |

| 12.0 mm+ | Minnesota, Embryological Collection (M.E.C.) | H. 16 |

| 14.0 mm | Cornell University, Embryological Collection (C.E.C.) | 5 |

| 17. 5 (?) | Harvard University, Embryological Collection (H.E.C.) | 839 |

| 18.0 mm | Carnegie Institution, Embryological Collection (C.I.E.C.) | 409 |

| 22.0 mm | Cornell University, Embryological Collection (C.E.C.) | 1 |

| Note: The following embryos have been studied, the right having been reconstructed in all cases. The embryos of which both lower limbs have been reconstructed are marked with an "+" | ||

| Reference: Senior HD. The development of the arteries of the human lower extremity. (1919) Amer. J Anat. 22:1-11. | ||

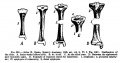

Limb Bone

Bone formation within the limb occurs by endochondral ossification of a pre-existing cartilage template. Ossification then replaces the existing cartilage except in the regions of articulation, where cartilage remains on the surface of the bone within the joint. Therefore bone development in the limb is initially about cartilage development or chondrogenesis.

|

|

| Upper Limb | Lower Limb |

|---|---|

| Arm Ossification | Leg Ossification |

| Mall (1906)[29] |

In addition, there are two quite separate aspects to this development.

- Pattern - where the specific regions will commence to form cartilage, which will be different for each cartilage element.

- Chondrogenesis - the differentiation of mesoderm to form cartilage, which will be essentially the same program for all cartilage templates.

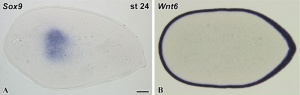

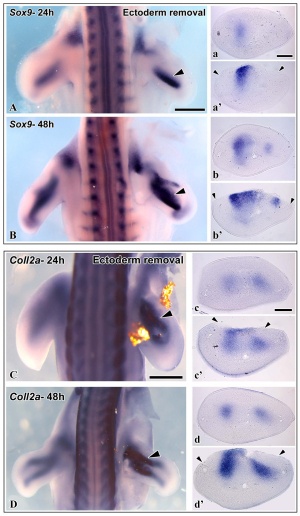

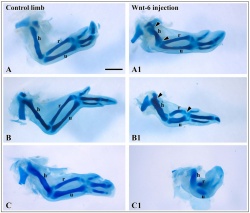

A recent study has identified that the overlying limb surface ectoderm potentially inhibits limb early chondrogenesis through Wnt6 signaling.[28]

Upper Limb Ossification

| Table Of Ossification Of The Bones Of The Superior Extremity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (Days and weeks refer to the prenatal, years to the postnatal period.) | |||

| Bone | Centres | Time of appearance of centre | Union of primary and secondary centres; remarks. |

| Clavicle | Diaphysis | 6th week | There are two centres in the shaft, a medial and a lateral. These blend on the 45th day (Mall). Shaft and epiphysis unite between the 20th and 25th years. |

| Sternal epiphysis | 18th to 20th year | ||

| Scapula | Primary centres: | The chief centre appears near the lateral angle. The subcoracoid centre appears at the base of the coracoid process and also gives rise to a part of the superior margin of the glenoid fossa. The coracoid process joins the body about the age of puberty. The acromial epiphysis centres (two or three in number) fuse with one another soon after their appearance and with the spine between the 22nd and 25th years (Quain); 20th year (Wilms). The subcoracoid and the epiphysis of the coracoid process, the glenoid fossa, the inferior angle, and the vertebral margin join between the 18th and 24th years in the order mentioned (Sappey). | |

| 1. That of the body, the spine, and the base of the glenoid cavity. | 8th week (Mall)2 | ||

| 2. Goraooid process | 1st year | ||

| 3. Subcoracoid | 10th to 12th year | ||

| Epiphyses: | |||

| Acromial epiphyses | 15th to 18th year | ||

| Epiphysis of the inferior angle. | 16 to 18th year | ||

| Epiphyses of the vertebral border. | 18th to 20th year | ||

| Epiphyses of upper surface of coracoid. | 16th to 18th year. | ||

| Epiphysis of surface of glenoid fossa. | 16th to 18th year. | ||

| Humerus | Diaphysis | 6th to 7th week (Mall) | The epiphyses of the head, the tuberculum majus and the tuberculum minus (the last is inconstant) unite with one another in 4th-6th year and with the shaft in 20th-25th year. The epiphyses of the capitulum, lateral epicondyle, and trochlea unite with one another and then in the 16th-17th year join the shaft. The epiphysis of the medial epicondyle joins the shaft in the 18th year. |

| Epiphyses: | |||

| Head | 1st to 2d year | ||

| Tuberculum majus | 2d to 3d year | ||

| Tuberculum minus | 3d to 5th year | ||

| Capitulum | 2d to 3d year | ||

| Epioondylus med | 5th to 8th year | ||

| Lateral margin of trochlea | 11th to 12th year | ||

| Epicondylus lat | 12th to 14th year | ||

| Radius | Diaphysis | 7th week (Mall) | The superior epiphysis and shaft unite between the 17th and 20th years. The inferior epiphysis and shaft about the 21st year (Pryor); M 21st year, F 21st-25th year (Sappey). Sometimes an epiphysis is found m the tuberosity (R. and K.) and in the styloid process (Sappey). |

| Epiphyses: | |||

| Carpal end | F 8th month - M 15th month (Pryor) | ||

| Humeral end | 6th-7th year | ||

| Ulna | Diaphysis | 7th week | The centre for the shaft of the ulna arises a few days later than that for the radius. The proximal epiphysis is united to the shaft about the 17th year; the inferior epiphysis between the 18th and 20th years; F 20th - 21st years, M 21st - 24th years (Sappey). There is sometimes an epiphysis in the styloid process (Sohwegel) and in the tip of the olecranon process (Sappey). |

| Epiphyses: | |||

| Carpal end | F 6th-7th year - M 7th-8th year (Pryor) | ||

| Humeral end | 10th year | ||

| Carpus | Os capitatum | F 3d-6th month M 4th-10th month | The navicular sometimes has two centres of ossification (Serres. Rambaud and Renault). Serres and Pryor have described two centres of ossification in the lunatum. Debierre has described two centres in the pisiform, one in a girl of eleven, the other in a boy of twelve. The OS hamatum may have a special centre for the hamular process. Pryor has found two centres in the triquetrum. Pryor (1908), describes the centres of ossification of the carpal bones as assuming shapes characteristic of each bone at an early period. |

| Os hamatum | F 5th-10th month M 6th-12th month | ||

| Os triquetrum | F 2d-3d year M about 3 years | ||

| Os lunatum | F 3rd-4th year M about 4 years | ||

| Os naviculare | F at 4 years, or early in 5th year M about 5 years | ||

| Os mult. maj. | F 4th-5th year M 5th-6th year | ||

| Osmult. min. | F 4th-5th year M 6th-6th year | ||

| Os pisiforme | F 9th-10th year M 12th-3th year | ||

| Metacarpals | Diaphyses | 9th week (Mall) | The centres for the shafts of the second and third metacarpals are the first to appear. There may be a distal epiphysis for the first metacarpal and a proximal epiphysis for the second. Pryor (1906). found the distal epiphysis of the first metacarpal in about 6 per cent, of cases. It is a family characteristic. It arises before the 4th year and unites later. Pryor found the proximal epiphysis of the second metacarpal in six out of two hundred families. It unites with the shaft between the 4th and 6th-7th year; sometimes, however, not until the 14th year. In the seal and some other animals all the metacarpals have proximal and distal epiphyses (Quain). The epiphyses join the shafts between the 15th and 20th years. There may bean independent epiphysis for the styloid process of the 5th metacarpal. The epiphysis of the metacarpal of the index finger appears first. This is followed by those of the 3d, 4th, 5th, and 1st digits. |

| Proximal epiphysis of the first metacarpal | 3d year | ||

| Distal epiphyses of the metacarpals | 2d year | ||

| Phalanges | Diaphyses | 9th week (Mall) | |

| First row | Proximal epiphyses | 1st-3rd year (Pryor) | The shafts of the phalanges of the second and third fingers are the first to show centres of ossification. The phalanges of the little finger are the last, the epiphysis in the middle finger is the first to appear. This is followed by those of the 4th, 2d, 5th, and 1st digits. |

| Middle row | Diaphyses | 11th-12th week (Mall) | The centres in the shafts of this row are the last to appear. The epiphysis of the phalanx of the middle finger is the first to appear. This is followed by those of the ring, index, and little finger (Pryor). |

| Proximal epiphyses | 2nd-3rd year | ||

| Terminal row | Diaphyses | 7th-8th week | The terminal phalanx of the thumb is the first to show a centre of ossification in the shaft. This is the first centre of ossification in the hand. It is developed in connective tissue while the centres of the other phalanges are developed in cartilage (Mall). The epiphysis of the ungual phalanx of the thumb is followed by those of the middle, ring, index, and little fingers. The fusion of the epiphyses of the phalanges with the diaphyses takes place in the 18th-20th year. |

| Proximal epiphyses | 2nd-3rd year | ||

| Sesamoid bones | Ossification begins generally in the 13th - 14th years, and may not take place until after middle life (Thilenius). For table of relative frequency in the embryo and adult see p. 385. | ||

M = male F = female.

| |||

Lower Limb Ossification

| Table Of Ossification Of The Bones Of The Inferior Extremity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (Days and weeks refer to the prenatal, years to the postnatal period.) | |||

| Bone | Centres | Time of appearance of centre | Time of fusion: general remarks |

| Os coxae | Os ilium | 56th day (Mall) | The rami of the ischium and the pubis are united by bone in the 7th or 8th year (Quain) ( 12-14 year Sappey). In the acetabulum the three hip bones are separated by a Y-shaped cartilage until after puberty. In this cartilage between the ilium and pubis the "os acetabuli" appears between the ninth and twelfth years. This bone, variable in size, forms a greater or less part of the pubic portion of the articular cavity. Leche (1884). Krause (1885), and many others consider it primarily an independent bone. About puberty between the ilium and ischium and over the acetabular surfaces of these bones small irregular epiphyseal centres appear. The os acetabuli becomes imited to the pubic bone about puberty and soon afterwards the acetabular portions of the ilium and ischium and the ischium and pubis begin to become united by bone. The acetabular portions of the pubis and ilium are unite a little later. Osseous union takes place earlier on the pelvic than on the articular surface of the acetabulum. The union of the several primary centres and the epiphyses is usually completed about the twentieth year. |

| Os ischii | 105th day (Mall) | ||

| Os pubis | 4th to 5th fetal month | ||

| Os acetabuli. | 9th to 12th year | ||

| Epiphyses:

Those of the acetabulum |

Soon after puberty | ||

| Crest of ilium | Soon after puberty | Fuses with main bone 20th to 25th year | |

| Tuberosity of ischium | Soon after puberty | Fusion begins in the 17th year and is completed between the 20th and 24th years (Sappey) | |

| Ischial spine | Soon after puberty | 18th to 20th year (Poirier). | |

| Ant. inf. spine of ilium | Soon after puberty | 18th to 20th year (Poirier) | |

| Symphysis end of os pubis (1 or 2 centres) | 18th to 20th year (Sappey) | After the 20th year | |

| Femur | Diaphysis | 43d day (Mall) | |

| Epiphyses:

Distal end |

Shortly before birth1 | 20th to 24th year | |

| Head | 1st year | 18th to 19th year | |

| Great trochanter | 3d to 4th year (Osseous granules soon after birth, (Poirier) | 18th year | |

| Small trochanter | 13th to 14th year

8th year (Sappey) |

17th year (Quain)

Proximal epiphysis 18th to 22d year (Poirier) | |

| Patella | 3d to 5th year | The osseous patella reaches its definitive form soon before puberty | |

| Tibia | Diaphysis | 44th day (Mall) | |

| Epiphyses:

Proximal end |

About birth | 19th to 24th year (Sappey) | |

| Distal end | 2d year | 16th to 19th year | |

| Tubercle (occas.) | 13th year | Fuses with epiphysis of the proximal end and then with this to the diaphysis | |

| Fibula | Diaphysis | 55th day (Mall). | |

| Epiphyses:

Distal end |

2d year | 20th to 22d year | |

| Proximal end | 3d to 5th year | 22d to 24th year | |

| Calcaneus | Chief centre | 6th fetal month | The chief nucleus is endochondral. A periosteal nucleus appears frequently in the 4-5 fetal month (Hasselwander) |

| Epiphysis (distal end) | 10th year (Quain)

7th-8th year ( Sappey) |

15th-16th year (Quain)

16th-18th year (Poirier) M 17-21, average 20 years F 13-17, average 16 years (Hasselwander) | |

| Talus | 6th fetal month (Hasselwander) | In the 7th-8th year the posterior part of the talus, the os trigonum, is frequently ossified from a special centre (v. Bardeleben). It fuses about the 18th year. | |

| Cuboid | About birth | ||

| Cuneiform III | 1st year | ||

| Cuneiform I | 2d-3d year | ||

| Cuneiform II | 3d-4th year | ||

| Navicular | 4th-5th year | ||

| Metatarsals | Diaphyses | 8th-10th week | According to v. Bardeleben a second centre of ossincation appears much later than the primary in the navicular, and finally about the time of puberty a medial epiphyseal centre arises. |

| Epiphyses | 3d-8th year | The centre for the 2d metatarsal usually appears first, then come the 3rd, 4th, 1st and 5th. The epiphysis of the 1st metatarsal appears at the proximal end of the bone: the other epiphyses arise at the distal ends of the metatarsals. There may be a distal epiphysis in the first metatarsal also.2 In some instances a proximal epiphysis is formed on the tuberosity of the fifth metatarsal (Gruber). The epiphyses unite with the shafts in the 17-21 year in males and in the 14-19 year in females. (Hasselwander). | |

| Phalanges: | |||

| Terminal row | Diaphyses | 58th day (Mall) | |

| Epiphyses (distal) | 4th year | M 13-23, average 16-21 year.

F 13-17, average 14-17 year (Hasselwander). | |

| Middle row | Diaphyses | 4th-10th fetal month | |

| Epiphyses | 3d year | M 15-19 year

F 13-16 year (Hasselwander) | |

| Proximal row | Diaphyses | 3d fetal month | |

| Epiphyses | 3d year | M 15-17 year.

F 14-15 year (Hasselwander) The centres for the shafts of the phalanges often appear double, one for the dorsal and one for the plantar surface. The centres for the medial phalanges in each row usually appear before the more laterally placed centres. The centre for the 5th terminal phalanx appears much later than the other centres in this row (Mall). According to Rambaud and Renault the epiphyses arise each from two centres which fuse together. In the terminal phalanx of the great toe the ossification centre of the epiphysis often appears as early as the second or even the first year. (Hasselwander) | |

| Sesamoid bones of the great toe | M 14th year

F 12th-13th year |

Ossification may begin in the 8th year in females, in the 11th in males (Hasselwander). | |

M = male F = female. | |||

Links: cartilage | bone | bone timeline

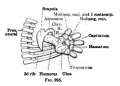

Shoulder and Pelvis

The skeletal shoulder consists of: the clavicle (collarbone), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the humerus. Development of his region occurs through both forms of ossification processes.

The skeletal pelvis consists of: the sacrum and coccyx (axial skeleton), and pelvic girdle formed by a pair of hip bones (appendicular skeleton). Before puberty, he pelvic girdle also consists of three unfused bones: the ilium, ischium, and pubis. In chicken, the entire pelvic girdle originates from the somatopleure mesoderm (somite levels 26 to 35) and the ilium, but not of the pubis and ischium, depends on somitic and ectodermal signals.[30]

- Links: Shoulder Development | Pelvis Development

Limb Skeletal Muscle

Embryonic skeletal muscles arise from the somite myotome region giving rise to myogenic progenitor cells.

In the chicken, myotome growth initially occurs by a contribution of myogenic progenitor cells from the medial border of the dermomyotome. Then later by progenitors from all four borders of the dermomyotome, with the medial and the lateral borders of the somite generate the epaxial and hypaxial muscles.[31] Depending on the somite level within the body (trunk), limb or between the limbs, myotome cells will then give rise to limb and trunk muscles respectively.[32]

- limb level somites - cells from the hypaxial (ventrolateral) lips of the dermomyotome delaminate and migrate into the limb bud to form the musculature of the limbs.

- between the limbs somites - cells delaminate from the edges or lips of the epithelial dermomyotome to form the subjacent postmitotic myotome, which gives rise to trunk muscles.

Myogenesis

- Early myogenic progenitor cells in the dermomyotome can be initially identified by the transcription factor Pax3.

- Subsequent myogenic program development then depends on the myogenic determination factors (Myf5, MyoD, and MRF4), both Myf5 and MyoD are expressed in the limbs.

- Final differentiation of these cells into post-mitotic muscle fibers in the limb bud is regulated by another myogenic determination factor, Myogenin.

(Some of the above text modified from[32])

- Links: Muscle Development | 1910 Limb Muscles

Wing as Limb Model

- chicken wing easy to manipulate

- removal, addition and rotation of limb regions

- grafting additional AER, ZPA

- implanting growth factor secreting structures

Mouse Limb Model

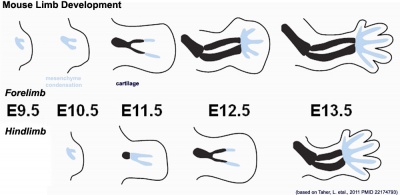

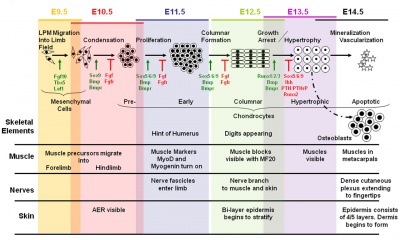

|

|

| Mouse limb skeleton cartoon[17]

Fore-limb and hind-limb buds for stages E9.5 to E13.5. Hindlimbs are morphologically delayed by about half a day.

|

Change in cell types and tissue formation as a function of mouse developmental stage.[17] |

Forelimb

Mouse forelimb cartilage and bone (E14.5 E18.5)

Hindlimb

- Links: Mouse Development

Bat Limb Model

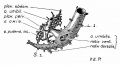

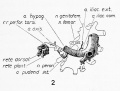

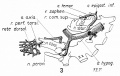

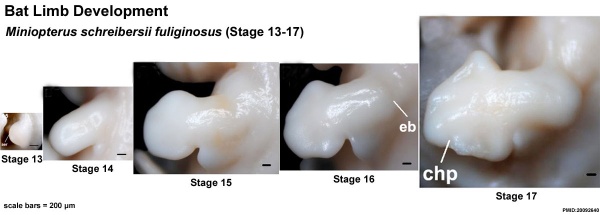

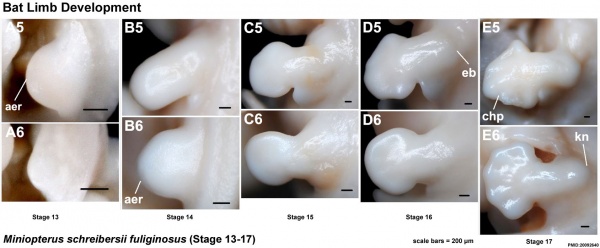

Images of the bat embryo Miniopterus schreibersii fuliginosus at embryonic Stages 13-17.[33]

(aer - apical ectodermal ridge; chp - chiropatagium; eb - elbow; kn - knee)

- Links: Bat Limb Development | Bat Development

Molecular

Fibroblast Growth Factors

| Human FGF Family | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Links: Fibroblast Growth Factor

Bone Morphogenetic Protein

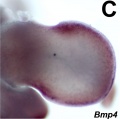

- Bmp2, Bmp4 and Bmp7 - co-required in the mouse AER for normal digit patterning but not limb outgrowth[35]

| Human BMP Family | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Links: Bone Morphogenetic Protein

T-box Transcription Factors

Hand2

The HAND2 gene encodes a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH).

- Links: Fibroblast Growth Factor | sonic hedgehog | Wnt | Hand2 | OMIM

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kicheva A & Briscoe J. (2010). Limbs made to measure. PLoS Biol. , 8, e1000421. PMID: 20644713 DOI.

- ↑ Jhanwar S, Malkmus J, Stolte J, Romashkina O, Zuniga A & Zeller R. (2021). Conserved and species-specific chromatin remodeling and regulatory dynamics during mouse and chicken limb bud development. Nat Commun , 12, 5685. PMID: 34584102 DOI.

- ↑ Bastida MF, Pérez-Gómez R, Trofka A, Zhu J, Rada-Iglesias A, Sheth R, Stadler HS, Mackem S & Ros MA. (2020). The formation of the thumb requires direct modulation of Gli3 transcription by Hoxa13. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , 117, 1090-1096. PMID: 31896583 DOI.

- ↑ Atsuta Y, Tomizawa RR, Levin M & Tabin CJ. (2019). L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel CaV1.2 regulates chondrogenesis during limb development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , 116, 21592-21601. PMID: 31591237 DOI.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Davey MG, Towers M, Vargesson N & Tickle C. (2018). The chick limb: embryology, genetics and teratology. Int. J. Dev. Biol. , 62, 85-95. PMID: 29616743 DOI.

- ↑ Rhodes CS, Matsunobu T & Yamada Y. (2019). Analysis of a limb-specific regulatory element in the promoter of the link protein gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. , 518, 672-677. PMID: 31470976 DOI.

- ↑ Potuijt JWP, Baas M, Sukenik-Halevy R, Douben H, Nguyen P, Venter DJ, Gallagher R, Swagemakers SM, Hovius SER, van Nieuwenhoven CA, Galjaard RH, van der Spek PJ, Ahituv N & de Klein A. (2018). A point mutation in the pre-ZRS disrupts sonic hedgehog expression in the limb bud and results in triphalangeal thumb-polysyndactyly syndrome. Genet. Med. , , . PMID: 29543231 DOI.

- ↑ Ohmura Y, Morokuma S, Kato K & Kuniyoshi Y. (2018). Species-specific Posture of Human Foetus in Late First Trimester. Sci Rep , 8, 27. PMID: 29311655 DOI.

- ↑ Nakamura T, Gehrke AR, Lemberg J, Szymaszek J & Shubin NH. (2016). Digits and fin rays share common developmental histories. Nature , 537, 225-228. PMID: 27533041 DOI.

- ↑ Masselink W, Cole NJ, Fenyes F, Berger S, Sonntag C, Wood A, Nguyen PD, Cohen N, Knopf F, Weidinger G, Hall TE & Currie PD. (2016). A somitic contribution to the apical ectodermal ridge is essential for fin formation. Nature , 535, 542-6. PMID: 27437584 DOI.

- ↑ Keenan SR & Beck CW. (2016). Xenopus Limb bud morphogenesis. Dev. Dyn. , 245, 233-43. PMID: 26404044 DOI.

- ↑ Huettl RE, Luxenhofer G, Bianchi E, Haupt C, Joshi R, Prochiantz A & Huber AB. (2015). Engrailed 1 mediates correct formation of limb innervation through two distinct mechanisms. PLoS ONE , 10, e0118505. PMID: 25710467 DOI.

- ↑ Tickle C. (2015). How the embryo makes a limb: determination, polarity and identity. J. Anat. , 227, 418-30. PMID: 26249743 DOI.

- ↑ Mayeuf-Louchart A, Lagha M, Danckaert A, Rocancourt D, Relaix F, Vincent SD & Buckingham M. (2014). Notch regulation of myogenic versus endothelial fates of cells that migrate from the somite to the limb. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , 111, 8844-9. PMID: 24927569 DOI.

- ↑ Kozhemyakina E, Ionescu A & Lassar AB. (2014). GATA6 is a crucial regulator of Shh in the limb bud. PLoS Genet. , 10, e1004072. PMID: 24415953 DOI.

- ↑ Christen B, Rodrigues AM, Monasterio MB, Roig CF & Izpisua Belmonte JC. (2012). Transient downregulation of Bmp signalling induces extra limbs in vertebrates. Development , 139, 2557-65. PMID: 22675213 DOI.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Taher L, Collette NM, Murugesh D, Maxwell E, Ovcharenko I & Loots GG. (2011). Global gene expression analysis of murine limb development. PLoS ONE , 6, e28358. PMID: 22174793 DOI.

- ↑ Boehm B, Westerberg H, Lesnicar-Pucko G, Raja S, Rautschka M, Cotterell J, Swoger J & Sharpe J. (2010). The role of spatially controlled cell proliferation in limb bud morphogenesis. PLoS Biol. , 8, e1000420. PMID: 20644711 DOI.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Galli A, Robay D, Osterwalder M, Bao X, Bénazet JD, Tariq M, Paro R, Mackem S & Zeller R. (2010). Distinct roles of Hand2 in initiating polarity and posterior Shh expression during the onset of mouse limb bud development. PLoS Genet. , 6, e1000901. PMID: 20386744 DOI.

- ↑ Satoh A, Makanae A & Wada N. (2010). The apical ectodermal ridge (AER) can be re-induced by wounding, wnt-2b, and fgf-10 in the chicken limb bud. Dev. Biol. , 342, 157-68. PMID: 20347761 DOI.

- ↑ Dai M, Wang Y, Fang L, Irwin DM, Zhu T, Zhang J, Zhang S & Wang Z. (2014). Differential expression of Meis2, Mab21l2 and Tbx3 during limb development associated with diversification of limb morphology in mammals. PLoS ONE , 9, e106100. PMID: 25166052 DOI.

- ↑ Agarwal P, Wylie JN, Galceran J, Arkhitko O, Li C, Deng C, Grosschedl R & Bruneau BG. (2003). Tbx5 is essential for forelimb bud initiation following patterning of the limb field in the mouse embryo. Development , 130, 623-33. PMID: 12490567

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Bandyopadhyay A, Tsuji K, Cox K, Harfe BD, Rosen V & Tabin CJ. (2006). Genetic analysis of the roles of BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7 in limb patterning and skeletogenesis. PLoS Genet. , 2, e216. PMID: 17194222 DOI.

- ↑ Farin HF, Lüdtke TH, Schmidt MK, Placzko S, Schuster-Gossler K, Petry M, Christoffels VM & Kispert A. (2013). Tbx2 terminates shh/fgf signaling in the developing mouse limb bud by direct repression of gremlin1. PLoS Genet. , 9, e1003467. PMID: 23633963 DOI.

- ↑ Osterwalder M, Speziale D, Shoukry M, Mohan R, Ivanek R, Kohler M, Beisel C, Wen X, Scales SJ, Christoffels VM, Visel A, Lopez-Rios J & Zeller R. (2014). HAND2 targets define a network of transcriptional regulators that compartmentalize the early limb bud mesenchyme. Dev. Cell , 31, 345-57. PMID: 25453830 DOI.

- ↑ ten Broek CM, Bots J, Varela-Lasheras I, Bugiani M, Galis F & Van Dongen S. (2013). Amniotic fluid deficiency and congenital abnormalities both influence fluctuating asymmetry in developing limbs of human deceased fetuses. PLoS ONE , 8, e81824. PMID: 24312362 DOI.

- ↑ Senior HD. The development of the arteries of the human lower extremity. (1919) Amer. J Anat. 22:1-11.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Geetha-Loganathan P, Nimmagadda S, Christ B, Huang R & Scaal M. (2010). Ectodermal Wnt6 is an early negative regulator of limb chondrogenesis in the chicken embryo. BMC Dev. Biol. , 10, 32. PMID: 20334703 DOI.

- ↑ Mall FP. On ossification centers in human embryos less than one hundred days old. (1906) Amer. J Anat. 5:433-458.

- ↑ Malashichev Y, Christ B & Pröls F. (2008). Avian pelvis originates from lateral plate mesoderm and its development requires signals from both ectoderm and paraxial mesoderm. Cell Tissue Res. , 331, 595-604. PMID: 18087724 DOI.

- ↑ Gros J, Scaal M & Marcelle C. (2004). A two-step mechanism for myotome formation in chick. Dev. Cell , 6, 875-82. PMID: 15177035 DOI.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Giordani J, Bajard L, Demignon J, Daubas P, Buckingham M & Maire P. (2007). Six proteins regulate the activation of Myf5 expression in embryonic mouse limbs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , 104, 11310-5. PMID: 17592144 DOI.

- ↑ Wang Z, Han N, Racey PA, Ru B & He G. (2010). A comparative study of prenatal development in Miniopterus schreibersii fuliginosus, Hipposideros armiger and H. pratti. BMC Dev. Biol. , 10, 10. PMID: 20092640 DOI.

- ↑ Yu SR, Burkhardt M, Nowak M, Ries J, Petrásek Z, Scholpp S, Schwille P & Brand M. (2009). Fgf8 morphogen gradient forms by a source-sink mechanism with freely diffusing molecules. Nature , 461, 533-6. PMID: 19741606 DOI.

- ↑ Choi KS, Lee C, Maatouk DM & Harfe BD. (2012). Bmp2, Bmp4 and Bmp7 are co-required in the mouse AER for normal digit patterning but not limb outgrowth. PLoS ONE , 7, e37826. PMID: 22662233 DOI.

Reviews

Glimm T, Bhat R & Newman SA. (2020). Multiscale modeling of vertebrate limb development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med , 12, e1485. PMID: 32212250 DOI.

Feneck E & Logan M. (2020). The Role of Retinoic Acid in Establishing the Early Limb Bud. Biomolecules , 10, . PMID: 32079177 DOI.

Tickle C. (2015). How the embryo makes a limb: determination, polarity and identity. J. Anat. , 227, 418-30. PMID: 26249743 DOI.

Cotney J, Leng J, Yin J, Reilly SK, DeMare LE, Emera D, Ayoub AE, Rakic P & Noonan JP. (2013). The evolution of lineage-specific regulatory activities in the human embryonic limb. Cell , 154, 185-96. PMID: 23827682 DOI.

Wagner GP & Vargas AO. (2008). On the nature of thumbs. Genome Biol. , 9, 213. PMID: 18341703 DOI.

Hill RE. (2007). How to make a zone of polarizing activity: insights into limb development via the abnormality preaxial polydactyly. Dev. Growth Differ. , 49, 439-48. PMID: 17661738 DOI.

Articles

Satoh A, Makanae A & Wada N. (2010). The apical ectodermal ridge (AER) can be re-induced by wounding, wnt-2b, and fgf-10 in the chicken limb bud. Dev. Biol. , 342, 157-68. PMID: 20347761 DOI.

Galli A, Robay D, Osterwalder M, Bao X, Bénazet JD, Tariq M, Paro R, Mackem S & Zeller R. (2010). Distinct roles of Hand2 in initiating polarity and posterior Shh expression during the onset of mouse limb bud development. PLoS Genet. , 6, e1000901. PMID: 20386744 DOI.

Stefanov EK, Ferrage JM, Parchim NF, Lee CE, Reginelli AD, Taché M & Anderson RA. (2009). Modification of the zone of polarizing activity signal by trypsin. Dev. Growth Differ. , 51, 123-33. PMID: 19207183 DOI.

Rodríguez-Niedenführ M, Burton GJ, Deu J & Sañudo JR. (2001). Development of the arterial pattern in the upper limb of staged human embryos: normal development and anatomic variations. J. Anat. , 199, 407-17. PMID: 11693301

Search PubMed

Search April 2010

- Limb Development - All (776) Review (108) Free Full Text (196)

- apical ectodermal ridge - All (95) Review (2) Free Full Text (31)

- zone polarizing activity - All (15) Review (2) Free Full Text (7)

Search Pubmed: Limb Development | apical ectodermal ridge | zone polarizing activity | limb bud skeletal muscle

Additional Images

Historic Images

- Limb Images: 274-278 Spinal Column and Lower Limb | 279-284 Lower Limb | 285-288 Knee | 289 Os Coxae | 290 Femur | 291 Tibia | 292 Fibula | 293 Foot | 294 | 295 | 296 | 297 | 298-299 | 300 Forearm and Hand | 301 Upper Limb Joints | 302 Clavicle | Upper Limb Ossification 1 | Upper Limb Ossification 2 | Bone Development Timeline

- Skeleton and Connective Tissues: Connective Tissue Histogenesis | Skeletal Morphogenesis | Chorda Dorsalis | Vertebral Column and Thorax | Limb Skeleton | Skull Hyoid Bone Larynx

Keith, A. (1902) Human Embryology and Morphology. London: Edward Arnold. Chapter 20. The Limbs

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- Embryo Images - apical ectodermal ridge | AER and vascular channel

- The Jackson Laboratory - Mouse Strains - Limb Patterning Defects

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Musculoskeletal System - Limb Development. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Musculoskeletal_System_-_Limb_Development

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G