Abnormal Development - TORCH Infections

| Embryology - 19 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| Educational Use Only - Embryology is an educational resource for learning concepts in embryological development, no clinical information is provided and content should not be used for any other purpose. |

Introduction

Congenital infections, collectively grouped under the acronym TORCH for Toxoplasmosis, Other organisms (parvovirus, HIV, Epstein-Barr, herpes 6 and 8, varicella, syphilis, enterovirus) , Rubella, Cytomegalovirus and Hepatitis. Several additional infections should now be added to this category such as: varicella virus, parvovirus, and Zika virus,

Note some of these infections have additional pages and also see related pages on maternal hyperthermia and bacterial infections.

Materal effects should really be called environmental (in contrast to genetic) removing the association of mother with the deleterious agent. Accepting this caveat, there are several maternal effects from lifestyle, environment and nutrition that can be prevented or decreased by change which is not an option for genetic effects.

Finally, when studying this topic remember the concept of "critical periods" of development that will affect the overall impact of the above listed factors. This can be extended to the potential differences between prenatal and postnatal effects, for example with infections and outcomes.

| Abnormality Links: abnormal development | abnormal genetic | abnormal environmental | Unknown | teratogens | ectopic pregnancy | cardiovascular abnormalities | coelom abnormalities | endocrine abnormalities | gastrointestinal abnormalities | genital abnormalities | head abnormalities | integumentary abnormalities | musculoskeletal abnormalities | limb abnormalities | neural abnormalities | neural crest abnormalities | placenta abnormalities | renal abnormalities | respiratory abnormalities | hearing abnormalities | vision abnormalities | twinning | Developmental Origins of Health and Disease | ICD-11 | ||

|

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: TORCH Infections |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

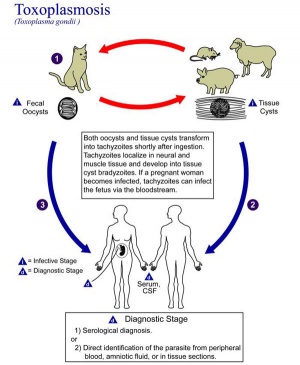

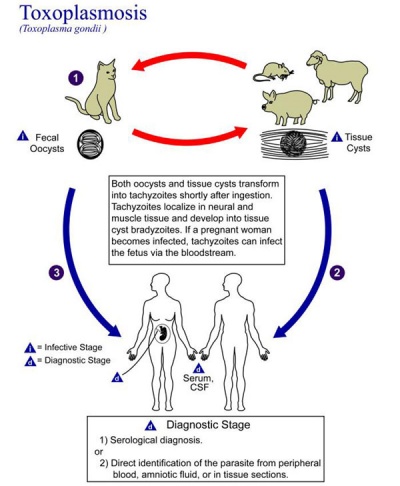

Toxoplasmosis

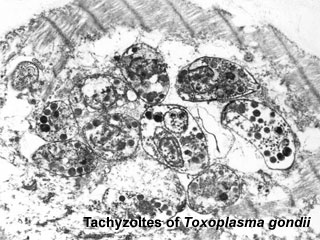

The causal agent of Toxoplasmosis is the protist Toxoplasma gondii. This unicellular eukaryote is a member of the phylum Apicomplexa which includes other parasites responsible for a variety of diseases (malaria, cryptosporidiosis). The diagnosis and timing of an infection are diagnostically based on serological tests.

|

|

| Toxoplasmosis lifecycle | Toxoplasma tachyzoites |

Recent findings suggest that pre-pregnancy immunization against toxoplasmosis may not protect against reinfection by atypical strains.

- Links: Toxoplasmosis

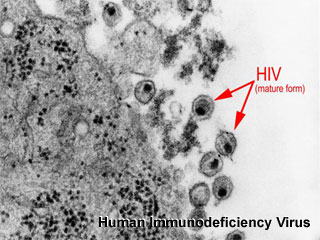

Other Organisms

A general term covering a ranges of viruses: parvovirus, HIV, Epstein-Barr, herpes 6 and 8, varicella, syphilis, enterovirus.

Links: Abnormal Development - Viral Infection

Rubella

Rubella virus (Latin, rubella = little red) is also known as "German Measles" due to early citation in German medical literature. Infection during pregnancy can cause congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) with serious malformations of the developing fetus. This association between infection and abnormal development was first identified in 1941.[9] The type and degree of abnormality relates to the time of maternal infection.

|

|

| Infant rubella virus | Rubella virus (electron micrograph |

- Links: Rubella Virus

Cytomegalovirus

|

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV, Greek, cyto = "cell", megalo = "large") or Human Herpesvirus 5 (HHV-5) is a member of the herpes virus family. A viral infection that causes systemic infection and extensive brain damage and cell death by necrosis. HCMV infection is ranked as one of the most common infections in adults, with the seropositive rates ranging from 60–99% globally. In Western countries, adults with advanced AIDS prior to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) this virus also a cause of blindness (CMV retinitis) and death in patients. |

|

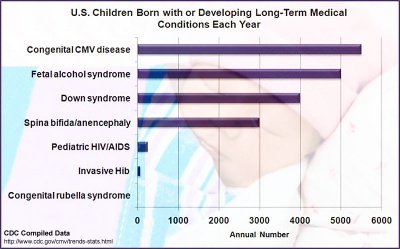

Estimated annual number of United States children with long-term sequelae caused by various disease conditions.[10] Congenital cytomegalovirus data are from a literature review, with varying collection periods spanning multiple years. Assumes 4 million live births per year and 20 million children less than 5 years of age. Where applicable, numbers represent means of published estimates. All estimates should be considered useful for rough comparisons only since surveillance methodology, time periods, and diagnostic accuracy varied by study. |

|

- Links: Cytomegalovirus | Torch Infections | Trisomy 21 | Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

Hepatitis

|

Hepatitis (inflammation of the liver) is caused in humans by one of 7 viruses (A, B, C, D, E) with the 2 additional F has not been confirmed as a distinct genotype; and G is a newly described flavivirus.

"All of these viruses can cause an acute disease with symptoms lasting several weeks including yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice); dark urine; extreme fatigue; nausea; vomiting and abdominal pain. It can take several months to a year to feel fit again." (CDC text). Virus particles measure 42nm in overall diameter and contain a 27nm diameter DNA-based core. |

Hepatitis Transmission Risk to the Fetus

- Hepatitis A - Fetal transmission of virus occurs with extreme rarity.

- Hepatitis B - Can occur as a consequence of intrapartum exposure, transplacental transmission, and breastfeeding.

20%–30% of HBsAg-positive/HbeAg-negative women will transmit virus to their infants. 90% of HBsAg- and HBeAg-positive women will transmit virus to their infants. Immunoprophylaxis at birth with both HBIG and Hepatitis B vaccine within 12 hours of birth decreases the risk of transmission. Passive (HBIG) and active immunization is 85%–95% effective in preventing neonatal HBV infection.

- Hepatitis C - The overall risk of transmission is approximately 5%–10% with unknown maternal viral titers.

All pregnant women with HCV should have viral titers performed.

Data: Hepatitis and reproduction[11]

- Links: Hepatitis Virus

References

- ↑ Borges M, Magalhães Silva T, Brito C, Teixeira N & Roberts CW. (2019). How does toxoplasmosis affect the maternal-foetal immune interface and pregnancy?. Parasite Immunol. , 41, e12606. PMID: 30471137 DOI.

- ↑ Chen L, Liu J, Shi L, Song Y, Song Y, Gao Y, Dong Y, Li L, Shen M, Zhai Y & Cao Z. (2019). Seasonal influence on TORCH infection and analysis of multi-positive samples with indirect immunofluorescence assay. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. , 33, e22828. PMID: 30666721 DOI.

- ↑ Leeper C & Lutzkanin A. (2018). Infections During Pregnancy. Prim. Care , 45, 567-586. PMID: 30115342 DOI.

- ↑ Moreira-Soto A, Cabral R, Pedroso C, Eschbach-Bludau M, Rockstroh A, Vargas LA, Postigo-Hidalgo I, Luz E, Sampaio GS, Drosten C, Netto EM, Jaenisch T, Ulbert S, Sarno M, Brites C & Drexler JF. (2018). Exhaustive TORCH Pathogen Diagnostics Corroborate Zika Virus Etiology of Congenital Malformations in Northeastern Brazil. mSphere , 3, . PMID: 30089647 DOI.

- ↑ Chung MH, Shin CO & Lee J. (2018). TORCH (toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus) screening of small for gestational age and intrauterine growth restricted neonates: efficacy study in a single institute in Korea. Korean J Pediatr , 61, 114-120. PMID: 29713357 DOI.

- ↑ Vilibic-Cavlek T, Ljubin-Sternak S, Ban M, Kolaric B, Sviben M & Mlinaric-Galinovic G. (2011). Seroprevalence of TORCH infections in women of childbearing age in Croatia. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , 24, 280-3. PMID: 20476874 DOI.

- ↑ van der Weiden S, Steggerda SJ, Te Pas AB, Vossen AC, Walther FJ & Lopriore E. (2010). Routine TORCH screening is not warranted in neonates with subependymal cysts. Early Hum. Dev. , 86, 203-7. PMID: 20227842 DOI.

- ↑ Brogly SB, Abzug MJ, Watts DH, Cunningham CK, Williams PL, Oleske J, Conway D, Sperling RS, Spiegel H & Van Dyke RB. (2010). Birth defects among children born to human immunodeficiency virus-infected women: pediatric AIDS clinical trials protocols 219 and 219C. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. , 29, 721-7. PMID: 20539252 DOI.

- ↑ Gregg NM. (1991). Congenital cataract following German measles in the mother. 1941. Epidemiol. Infect. , 107, iii-xiv; discussion xiii-xiv. PMID: 1879476

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Congenital CMV Infection Trends and Statistics http://www.cdc.gov/cmv/trends-stats.html, viewed 6 November 2012 (EST).

- ↑ Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. (2008). Hepatitis and reproduction. Fertil. Steril. , 90, S226-35. PMID: 19007636 DOI.

Reviews

Nickerson JP, Richner B, Santy K, Lequin MH, Poretti A, Filippi CG & Huisman TA. (2012). Neuroimaging of pediatric intracranial infection--part 2: TORCH, viral, fungal, and parasitic infections. J Neuroimaging , 22, e52-63. PMID: 22309611 DOI.

Ishaque S, Yakoob MY, Imdad A, Goldenberg RL, Eisele TP & Bhutta ZA. (2011). Effectiveness of interventions to screen and manage infections during pregnancy on reducing stillbirths: a review. BMC Public Health , 11 Suppl 3, S3. PMID: 21501448 DOI.

Stegmann BJ & Carey JC. (2002). TORCH Infections. Toxoplasmosis, Other (syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19), Rubella, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Herpes infections. Curr Womens Health Rep , 2, 253-8. PMID: 12150751

Helfgott A. (1999). TORCH testing in HIV-infected women. Clin Obstet Gynecol , 42, 149-62; quiz 174-5. PMID: 10073308

Newton ER. (1999). Diagnosis of perinatal TORCH infections. Clin Obstet Gynecol , 42, 59-70; quiz 174-5. PMID: 10073301

Greenough A. (1994). The TORCH screen and intrauterine infections. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. , 70, F163-5. PMID: 8198407

. (1990). TORCH syndrome and TORCH screening. Lancet , 335, 1559-61. PMID: 1972489

Articles

Vilibic-Cavlek T, Ljubin-Sternak S, Ban M, Kolaric B, Sviben M & Mlinaric-Galinovic G. (2011). Seroprevalence of TORCH infections in women of childbearing age in Croatia. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , 24, 280-3. PMID: 20476874 DOI.

Abu-Madi MA, Behnke JM & Dabritz HA. (2010). Toxoplasma gondii seropositivity and co-infection with TORCH pathogens in high-risk patients from Qatar. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. , 82, 626-33. PMID: 20348511 DOI.

Kriebs JM. (2008). Breaking the cycle of infection: TORCH and other infections in women's health. J Midwifery Womens Health , 53, 173-4. PMID: 18455090 DOI.

Singh S. (2002). Prevalence of torch infections in Indian pregnant women. Indian J Med Microbiol , 20, 57-8. PMID: 17657031

Abdel-Fattah SA, Bhat A, Illanes S, Bartha JL & Carrington D. (2005). TORCH test for fetal medicine indications: only CMV is necessary in the United Kingdom. Prenat. Diagn. , 25, 1028-31. PMID: 16231309 DOI.

Search Pubmed

June 2010 "TORCH Infections" All (183) Review (37) Free Full Text (18)

Search Pubmed: TORCH Infections | maternal infections | teratogens

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 19) Embryology Abnormal Development - TORCH Infections. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_TORCH_Infections

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G