Abnormal Development - Viral Infection

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| Educational Use Only - Embryology is an educational resource for learning concepts in embryological development, no clinical information is provided and content should not be used for any other purpose. |

Introduction

Below is a list of some known viral infections maternal, embryonic, fetal, and postnatal that impact upon development. Only a very brief overview is given for each virus for more specific details see the listed internal and external links.

Viruses cannot reproduce by themselves and therefore infect cells to use the cell machinery to produce more virus. Different viruses have genetic material as single- or double-stranded RNA or DNA. The infectious virus particle is called a "virion" and is the genetic material packed in a protein shell. Viruses come in many genetic sizes, as little as 4 proteins up to 200 proteins.

Viral infections can range in their effects from no discernable impact through to severe impacts on development. Furthermore this may occur either directly by the infection or indirectly by the associated maternal fever and other side-effects of the infection. (More? hyperthermia)

Rubella virus "German Measles" infection during pregnancy is one of the most serious causing congenital rubella syndrome with serious malformations of the developing fetus.

Viral infections have also recently been in the news with the 2009 novel influenza A (H1N1) "Swine Flu" pandemic.

Some early postnatal viral infections can also impact upon development and have been the target for worldwide immunization and eradication.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) leads to AIDS and according to United Nations 2005 data about 38.6 million people had HIV. Of the 17.3 million women infected with HIV, 3.28 million gave birth each year (mostly in sub-Saharan Africa), leading to 700,000 new infections of HIV in children each year.

Note also that many cancers can be caused by viruses (papilloma viruses, hepatitis B and C viruses, Epstein-Barr virus and human T-cell lymphotropic virus). Virus-induced cancers account for about 20% of worldwide cancer incidence. In women, cervical cancer is caused by the human papillomavirus types (HPV16 and HPV18).

In a few developing countries, and mainly in Africa, at least 3 viruses induce a hemorrhagic fever: Ebola hemorrhagic fever, Marburg virus disease, and Lassa fever.

| Environmental Links: Introduction | low folic acid | iodine deficiency | Nutrition | Drugs | Australian Drug Categories | USA Drug Categories | thalidomide | herbal drugs | Illegal Drugs | smoking | Fetal Alcohol Syndrome | TORCH | viral infection | bacterial infection | fungal infection | zoonotic infection | toxoplasmosis | Malaria | maternal diabetes | maternal hypertension | maternal hyperthermia | Maternal Inflammation | Maternal Obesity | hypoxia | biological toxins | chemicals | heavy metals | air pollution | radiation | Prenatal Diagnosis | Neonatal Diagnosis | International Classification of Diseases | Fetal Origins Hypothesis |

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Abnormal Development Viral Infection | Abnormal Development Coronavirus |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

International Classification of Diseases

| ICD-11 KA62 Viral infection in the foetus or newborn |

|---|

Any condition affecting foetuses or newborns, caused by an infection with a virus.

|

| viral infection | environmental abnormalities | ICD-11 | Infections of the foetus or newborn |

| International Classification of Diseases - Viral infection | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Rubella Virus

Rubella virus (Latin, rubella = little red), also known as "German Measles" (due to early citation in German medical literature).

Infection during pregnancy can cause congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) with serious malformations of the developing fetus. The type and degree of abnormality relates to the time of maternal infection.

- Links: rubella virus

Cytomegalovirus

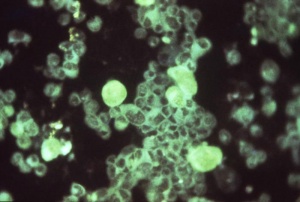

Immunoflourescent detection of Cytomegalovirus (Image: CDC USA) |

Viral infection causes systemic infection and extensive brain damage and cell death by necrosis. Cytomegalovirus infection can also occur in the human placenta.[16] |

- Links: Cytomegalovirus | Medical Microbiology- Cytomegalovirus | Search Medical Microbiology "Cytomegalovirus"

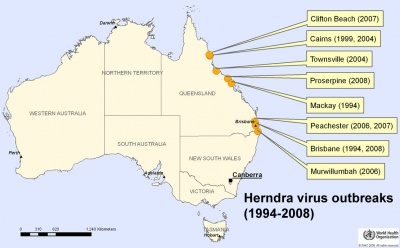

Hendra Virus

Australia map - hendra virus outbreaks (1994-2008) |

Hendra virus is a paramyxoviridae (ssRNA negative-strand virus) that mainly infects large fruit bats (flying foxes) which can be passed on to horses. The infection has occasionally been passed onto people who have been in close contact with an infected horse. There is evidence of fetal and placental infection in flying fox[17] and animal models.[18] There is currently insufficient information to determine whether there are developmental effects in humans.

Named after the Brisbane suburb where in 1994 the first outbreak was detected. Recently a vaccine for horses has been developed. |

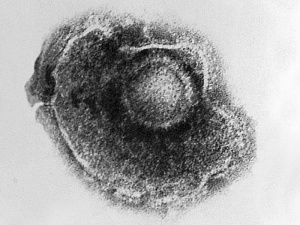

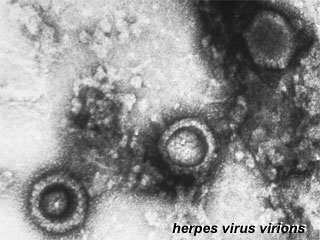

Herpes Simplex Virus

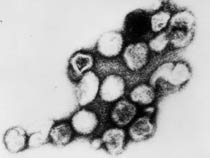

Herpes Virus, transmission electron micrograph (Image: CDC USA) |

Viral herpes simplex infection can cause a systemic infection and extensive brain damage and cell death by necrosis.

There is also some evidence which suggests that fetal exposure to herpesvirus infection is associated with pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders and preterm birth. |

NCBI Bookshelf (external link) Search Medical Microbiology "Herpes Simplex Virus"

Search PubMed: term = Herpes Simplex Virus teratology | embryo infection | fetal infection | neonatal infection

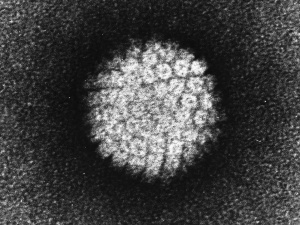

Human Papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus |

(HPV) A group of more that 118 identified viral strains about 40 infect the genital tract and 12 are known to be cancer-causing. Just eight HPV types 16, 18, 45, 33, 31, 52, 58, and 35 in descending order of frequency are responsible for more than 90 percent of cervical cancer cases. (Lancet 2010)

Infection can be detected by pap smear and at least 2 available vaccines, Cervarix (GSK) and Gardasil (Merck). Gardasil protects against HPV types 16 and 18, which cause 70% of cervical cancers in women and 90% of all HPV-related cancers in men. Also against two low-risk HPV types (types 6 and 11), which cause 90% of genital warts. through cross-protection also partially against HPV types 31 and 45. |

| Cervical Screening Program - HPV Vaccination Program |

|---|

| National Cervical Screening Program

Clinical term for the detection of DNA from specific strains of human papillomavirus (HPV) from cervical samples. In Australia, this test will replace the "Pap Smear" test that identified pathological cells. Specific types of HPV infections are known precursors of cervical cancer and are also being preventively treated by the HPV vaccine. (More? Cervical Screening Program | human papillomavirus | National Cervical Screening Program The National HPV Vaccination Program is for girls and boys aged 12 to 13 years. |

| HPV Vaccination Program

In Australia, the National HPV Vaccination Program is for girls and boys aged 12 to 13 years. (More? HPV vaccine) |

| ICD-11 Cervical Cancer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

- Links: human papillomavirus | cervical cancer | CDC STD Facts - Human papillomavirus | Medline Plus Human Papillomavirus | Cervical Screening Program)

Polio Virus

Poliomyelitis (polio) is a highly infectious viral disease, affecting only humans of any age, but mainly children under the age of 3 (> 50% cases) causing paralysis and death. There are three types (type 1, type 2, and type 3) of wild poliovirus which can invade the nervous system and can cause total paralysis in several hours. Polio cases have decreased by more than 99% since 1988.

- 1988 - estimated 350,000 cases in more than 125 endemic countries

- 2006 - 1997 reported cases

- 2008 - only parts of four countries in the world remain endemic for the disease

A bivalent oral polio vaccine (BOPV) is presently being used in countries with high existing polio rates, India and Nigeria. A recent WHO release has shown the largest ever year-to-year drop in polio cases following the use of BOPV:

- Nigeria - has seen a 98% drop in polio cases (2009 over 400 cases to 2010 just 9 so far)

- India - has seen a 90% drop during the same period.

- Links: Abnormal Development - Polio Virus | Polio Eradication Initiative | WHO - Africa seizes chance against polio

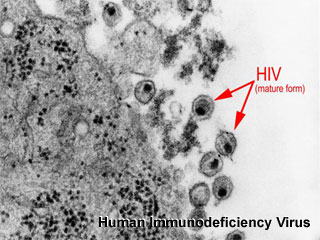

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

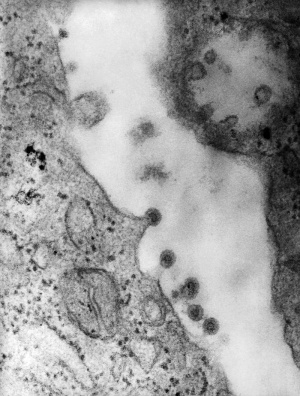

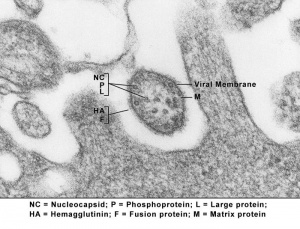

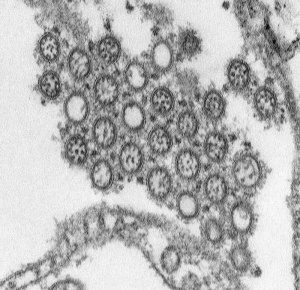

Human Immunodeficiency Virus, transmission electron micrograph (Image: CDC USA) |

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that causes Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Maternal transmission of HIV can occur perinatally in utero, during labour and delivery, or postnatally through breastfeeding and can be reduced by the use of antiretroviral treatment and avoidance of breastfeeding.

Neonatal infection diagnosis can be made by PCR from 6-12 week. UNAIDS, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, estimated that 38.6 million people had HIV (2005), 17.3 million were women. About 3.28 million pregnant women infected with HIV give birth each year (the majority in sub-Saharan Africa) leading to 700,000 new infections of HIV in children each year. (text modified from Gray and McIntyre, BMJ 2007;334:950-953) |

Links: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Hepatitis Virus

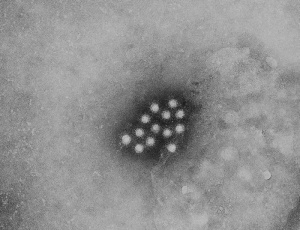

Hepatitis (inflammation of the liver) is caused in humans by one of 7 viruses (A, B, C, D, E) with the 2 additional F has not been confirmed as a distinct genotype; and G is a newly described flavivirus.

"All of these viruses can cause an acute disease with symptoms lasting several weeks including yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice); dark urine; extreme fatigue; nausea; vomiting and abdominal pain. It can take several months to a year to feel fit again." (CDC text).

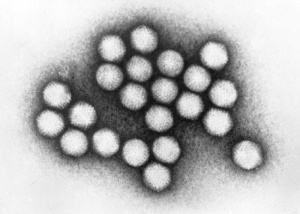

Virus particles measure 42nm in overall diameter and contain a 27nm diameter DNA-based core.

Hepatitis Transmission Risk to the Fetus

Hepatitis A

- Fetal transmission of virus occurs with extreme rarity.

Hepatitis B

- Can occur as a consequence of intrapartum exposure, transplacental transmission, and breastfeeding.

- 20% - 30% of HBsAg-positive/HbeAg-negative women will transmit virus to their infants.

- 90% of HBsAg- and HBeAg-positive women will transmit virus to their infants.

- Immunoprophylaxis at birth with both HBIG and Hepatitis B vaccine within 12 hours of birth decreases the risk of transmission.

- Passive (HBIG) and active immunization is 85-95% effective in preventing neonatal HBV infection.

Hepatitis C

- The overall risk of transmission is approximately 2-6% with unknown maternal viral titers.

- All pregnant women with HCV should have viral titers performed.

- The placenta appears to act as an immunological organ providing antiviral protection against hepatitis C viral transmission in the majority of cases.[19]

Hepatitis E virions (CDC)

Search PubMed: term = Hepatitis Virus teratology | embryo infection | fetal infection | neonatal infection

Influenza Virus

Flu is the general term and abbreviation of influenzaviral infections and the possible teratogenic effect of influenza viruses (orthomyxoviruses, "flu") is unclear, with very little evidence directly linking the two events. A relatively recent study was unable to identify any placental transmission of influenza virus during the second and third trimester. Severe maternal infection though may lead to hyperthermia, which has been demonstrated to be teratogenic, particularly in early neural development. (More? [hyperthermia.htm Maternal Hyperthermia])

Influenza virus infection in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy: a clinical and seroepidemiological study.[23] "We found no evidence for transplacental transmission of influenza virus or auto-antibody production in pregnancies complicated by influenza infections. There was an increase in the complications of pregnancy in our influenza cohort."

Postnatally, the suggested initial limited neonatal immune system makes postnatal infection dangerous.

See also: Transmission of influenza A in human beings.[24]

- Links: Medline Plus - Flu | Search Medical Microbiology "orthomyxovirus"

Measles

Measles (rubeola) is a paramyxovirus appearing mainly as a respiratory viral infection, clinically different from Rubella. A single-stranded RNA virus which is highly contagious. Before measles vaccination (USA 1963) more than 90% of children had an infection before puberty and in developing countries it is still a common and often fatal childhood disease. Childhood immunisation and immunity persists in only about 80% of adults.

Pregnancy effects of measles results in a higher risk of premature labor, spontaneous abortion, low-birth-weight, and possibly rare cases of birth defects with no definable pattern of malformation.[25]

In terms of the immune response to post-natal infection, a monkey model has shown that the virus is initially regulated by T cells, but require an antibody response to eliminate the viral RNA.[26]

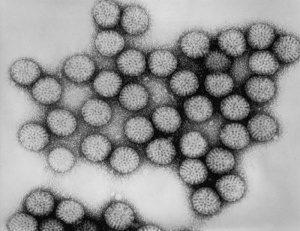

Rotavirus

A type of virus that is a common cause of diarrhoea and vomiting (viral gastroenteritis) in infants and young children. The live attenuated rotavirus vaccine is contraindicated in pregnancy, but can be safely administered to household contacts of pregnant women. There is only a very small risk of transmission of the rotavirus vaccine virus to a susceptible pregnant woman and there is no evidence of risk to the fetus if pregnant women are in contact with recently vaccinated individuals.

- Non-enveloped, icosahedral virus of the Reoviridae family containing a genome of 11 segments of double stranded RNA (dsRNA).

- Divided into seven serotypes (Rotavirus A–G).

(data based on: The Australian Immunisation Handbook 9th Edition 2008 2.3.2 Vaccination of women planning pregnancy, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and preterm infants - updated July 2009 )

- Links: Abnormal Development - Rotavirus | Postnatal - Vaccination | The Australian Immunisation Handbook 9th Edition 2008 | Australian Immunisation Handbook - Rotavirus | 2.3.2 Vaccination of women planning pregnancy, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and preterm infants - updated July 2009 | Medical Microbiology - Rotaviruses

Varicella Zoster Virus (chickenpox)

Fetal varicella syndrome (FVS) is caused by transplacental infection by the varicella zoster (chickenpox) virus following maternal infection.

Fetal and neonatal risks are dependent on infection timing.

- before 20 weeks (GA) - FVS can occur with an incidence of about 1%. The lesions can affect the skin, limbs, central and autonomous nervous systems, eyes, cause calcifications, and growth retardation; mortality is high. Lesions typically follow one or several nerve territories, suggesting that damage results from in utero zoster following primary fetal infection.

- during pregnancy - transmission can occur, but is usually asymptomatic; some infants develop zoster postnatally and a few have FVS.

- around delivery - often leads to disseminated neonatal varicella.

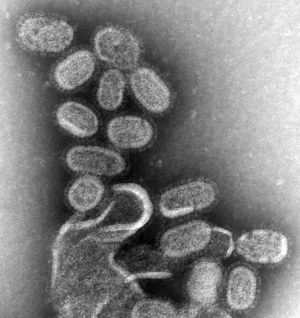

Swine Influenza Virus

In 2009 a global pandemic of the novel influenza A (H1N1) or Swine Flu has occurred. At this stage the possible teratogenic effect of this influenza virus should be considered the same as those described for the influenza virus above. The term "Pandemic" refers only to the spread of the virus, not the severity of the infection or potential developmental outcomes. This virus has also been spreading in an unseasonable pattern, that is in the northern hemisphere summer, when typically viral infections increase in the winter period.

H1 refers to one of the hemagglutinin subtypes (H1, H2 or H3) and N1 refers to one of the two neuraminidase subtypes (N1 or N2). Over the last century there have been at least three different human viral pandemic circulating strains H1N1 (1918, 1977), H2N2 (1957) and H3N2 (1968).

A study of the perinatal outcomes after maternal 2009/H1N1 infection: national cohort study.PubmedParser error: The PubmedParser extension received invalid XML data. ()

- "Perinatal mortality was higher in infants born to infected women (10 deaths among 256 infants; rate 39 (95% confidence interval 19 to 71) per 1000 total births) than in infants of uninfected women (9 deaths among 1233 infants; rate 7 (3 to 13) per 1000 total births) (P < 0.001). This was principally explained by an increase in the rate of stillbirth (27 per 1000 total births v 6 per 1000 total births; P = 0.001). Infants of infected women were also more likely to be born prematurely than were infants of comparison women (adjusted odds ratio 4.0, 95% confidence interval 2.7 to 5.9). Infected women who delivered preterm were more likely to be infected in their third trimester (P = 0.046), to have been admitted to an intensive care unit (P < 0.001), and to have a secondary pneumonia (P = 0.001) than were those who delivered at term."

| Region | Number of Confirmed Cases(10 July 2009 based upon online data) | Number of Confirmed Deaths |

| USA | 37,246 | 211 |

| Mexico | 11,699 | 121 |

| Canada | 9,717 | 39 |

| UK | 9,718 | 14 |

| Europe | 13,667 | 16 |

(Table data source: BMJ 2009;339:b2840)

Confirmed infections per million population (July 2009)

- Australia and New Zealand - 462

- Britain - 158

- USA - 118

Australia - H1N1 Influenza 09 (Human Swin Flu) Facts

- Incubation period: maximum = 7 days (3 days would be more common)

- Period of communicability: from 24 hours prior to the onset of symptoms until:

- adults 12-64 yrs = 7 days

- adults >65 yrs = 14 days

- children <12 yrs = 14 days (or until resolution of fever, whichever is longer)

- Means of virus transmission: most likely to be spread from person-to-person by inhalation of infectious droplets produced while talking, coughing and sneezing; transmission may also occur through direct and indirect (fomite) contact.

Australian State Information

- NSW http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/swine_flu.asp

- Public health offices in NSW Area Health Service Areas can be found at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/swine_flu.asp

- Victoria http://www.health.vic.gov.au/ideas/diseases/swine-influenza

- Queensland http://access.health.qld.gov.au/hid/InfectionsandParasites/ViralInfections/swineFlu2009_fs.asp and http://www.health.qld.gov.au/swineflu/html/hc_resources.asp

- WA http://www.public.health.wa.gov.au/2/949/2/swine_flu.pm and http://www.public.health.wa.gov.au/3/952/3/human_swine_flu_health_providers.pm

- SA http://www.flu.sa.gov.au/Swineflu.aspx and http://www.health.sa.gov.au/pandemicinfluenza/

- NT http://www.health.nt.gov.au/Centre_for_Disease_Control/index.aspx and http://www.health.nt.gov.au/Emergency_Management_and_Disaster_Arrangements/Pandemic/index.aspx

- Tasmania http://www.pandemic.tas.gov.au/ and http://www.pandemic.tas.gov.au/what_does_it_mean_to_you/health_sector

- ACT http://health.act.gov.au/c/health?a=da&did=10098808&pid=1240874209 and http://www.health.act.gov.au/c/health?a=da&did=11044035&pid=1242181681

(Facts from: Australian Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing H1N1 Influenza 09 (Human Swine influenza) – Summary Sheet for General Practitioners Current as of 24 May 2009)

UK Information

20 July 2009: Chief Medical Officer's advice to pregnant women"Some pregnant women who catch the H1N1 (swine) ‘flu virus will develop complications of the infection (including pneumonia) that could put their own and their baby’s health at risk. The risks are greatest in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. It is too early in the pandemic of influenza to be able to quantify these risks for the individual but most pregnant women who catch the disease are likely to make an uncomplicated recovery...."

Links: WHO - H1N1 Pandemic | USA CDC - H1N1 Flu | Medline Plus - H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu) | GenBank sequences from pandemic (H1N1) 2009 viruses

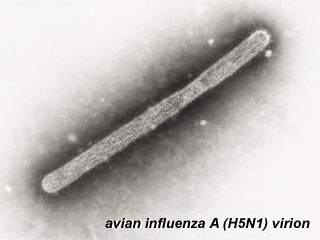

Avian Influenza Virus

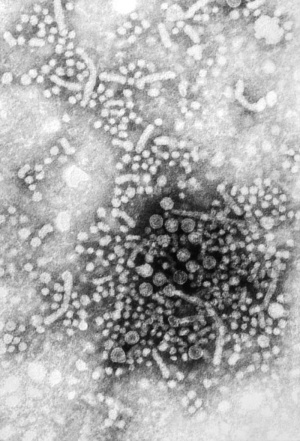

Avian Influenza virion (Image: CDC USA) Avian Influenza virion (Image: CDC USA) |

In 1997 the first instance of direct bird-to-human spread of influenza A (H5N1) virus was documented during an outbreak of avian influenza among poultry in Hong Kong.

The virus caused severe respiratory illness in 18 people (6 died) and there have been subsequent instances of other H5N1 infection. The virus does not typically infect humans, and there is no evidence yet of a direct effect on development. |

Lassa Virus

Lassa virions (Image: CDC USA) Lassa virions (Image: CDC USA) |

Lassa virus (LASV) of the arenaviridae family, a single-stranded RNA virus (see review[27]). First isolated in 1969 from a missionary nurse who worked in a clinic the small town of Lassa, Nigeria. The virus is the causative agent of a hemorrhagic fever and can be transmitted between species (zoonotic). Death rates are high for women in the third trimester of pregnancy. Fetal death (95%) occurs in uterus of infected pregnant mothers.

|

Ebola Virus

Ebola virus disease (EVD, Ebola hemorrhagic fever, or EHF) is caused by three of the four species of “Ebola-like viruses” that appear to be maintained in a natural reservoir in the rain forests of Africa.

Ljungan virus

Zoonotic Ljungan virus associated with central nervous system malformations in terminated pregnancy.[28]

- "LV was diagnosed in 9 of 10 cases with hydrocephalus and in 1 of 18 trisomy 21 controls by immunohistochemistry. Five of nine cases with anencephaly had a positive PCR result, whereas none of the 12 trisomy 21 available for PCR testing had a positive result. The 47 newborn mice exposed to LV all developed encephalitis, with eight having hydrocephalus. None of the 52 control animals had encephalitis or hydrocephalus."

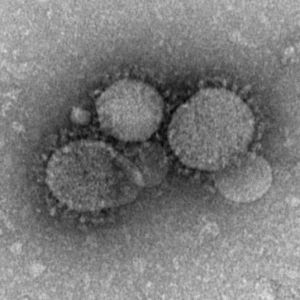

Coronaviruses (Latin corona = crown or halo) name refers to the appearance of their virions, due to the presence of a "crown" of surface spikes. Several of the coronavirus infections in humans occur initially as respiratory infections that originated from animal contact as a zoonotic infection.

Search PubMed: Abnormal Development Coronavirus | Coronavirus teratogen | SARS Coronavirus teratogen

First reported in Wuhan, China in 2019[29] and it is too soon to establish the fetal effects of infection[30] and is currently thought to be clinically milder than either SARS or MERS.

- Links: CDC

First reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012, has a mortality rate of approximately 34.5%[31] and in pregnancy has resulted in fetal death in 27% of cases.[32] MERS-CoV is a zoonotic infection with the primary reservoir thought to be camels or camel products.

Impact of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) on pregnancy and perinatal outcome.[33]

- "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) known to cause severe acute respiratory illness associated with a high risk of mortality Various factors may have contributed to the successful outcome of this patient such as young age, presentation during the last stages of pregnancy, and possible differences in immune response."

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

First reported in China in 2002, and later in Asia in 2003, with a mortality rate of approximately 10%. SARS is a zoonotic infection with the primary reservoir of bats and the intermediary source was civet cats.

Adenovirus

1953 - Human adenovirus was first isolated. This virus family is the causative agent of membrane infections in: respiratory tract, eyes, gastrointestinal tract, and urinary tract.

- Adenovirus spherical virons are 70 - 90 nm in diameter.

- Adenoviruses have a double-stranded linear DNA structure.

- There are about 51 antigenically unique serotypes (species) grouped into six subgenera (A - F).

Modified adenovirus is currently used as a research tool to introduce genes into cells in vitro and in animal systems.[34]

- Links: Medical Microbiology - Adenoviruses | Search Medical Microbiology "adenovirus"

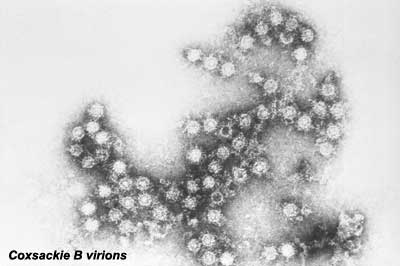

Coxsackie

|

Coxsackie B virus are 6 pathogenic enteroviruses with a range of adult illness from mild gastrointestinal to pericarditis and myocarditis. These viruses may cause an increase in early spontaneous abortions and rarely a fetal myocarditis. |

Echoviruses

Echoviruses are RNA viruses found in the gastrointestinal tract that belongs to the genus Enterovirus of the Picornaviridae family. These viruses do not seem to damage the fetus.

Mumps

| Mumps (epidemic parotitis) is a viral inflammation of the parotid glands, which are the major salivary glands in humans. This viral infection may cause increased early and late fetal death and neonatal mumps. Note that parotid inflammation can also occur during bacterial infections. |

Marburg Virus

Marburg virions (Image: CDC USA) Marburg virions (Image: CDC USA) |

Marburg RNA virus of the filovirus family, causes hemorrhagic fever in both humans and non-human primates and is a very rare. Virus has characteristic "Shepherd’s Crook" shape. |

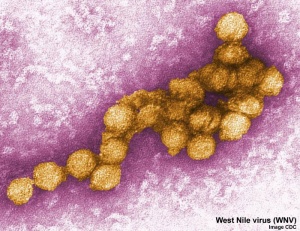

West Nile Virus

West Nile virus (WNV) activity reported by state, United States, 2012 (as of September 11, 2012) |

"Since 1999, more than 30,000 people in the United States have been reported as getting sick with West Nile virus. Infected mosquitoes spread West Nile virus (WNV) that can cause serious, life altering disease."[35] A 2006 study of 72 infected infants (2003 and 2004) "almost all seemed normal, and none had conclusive laboratory evidence of congenital WNV infection. ...Three infants had WNV infection that could have been congenitally acquired, seven infants had major malformations, but only 3 of these had defects that could have been caused by maternal WNV infection based on the timing of the infections and the sensitive developmental period for the specific malformations, and none had any conclusive evidence of WNV etiology."[36] A 2017 study of Zika virus, an identified teratogen, and West Nile virus appears that WNV did not to increase the risk for adverse birth outcomes, although teratogenicity could not been excluded.[37]

|

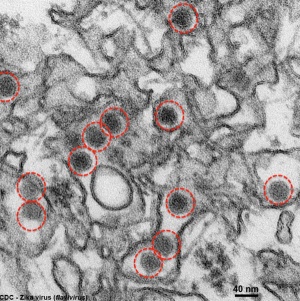

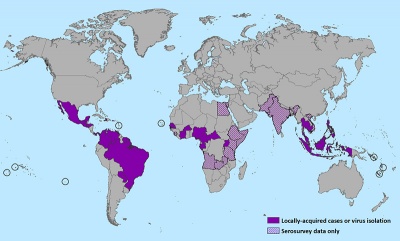

Zika Virus

|

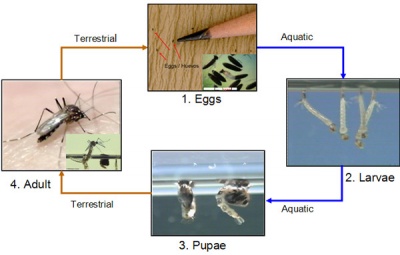

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-borne flavivirus related to dengue virus first isolated from a rhesus monkey in Zika forest, Uganda (1947). Transmitted by mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) it was then identified in humans in Nigeria in 1954 and subsequently in South America, Asia and Pacific regions. More recently in Australia from returning travellers.[38]

Virus particles are 40 nm in diameter, with an outer envelope, and an inner dense core. ZIKV is an RNA virus containing 10,794 nucleotides encoding 3,419 amino acids.[39] Mosquito bites lead to an initial infection of skin cells.[40] The virus may also be transmitted transplacentally or during delivery.[41] Some limited evidence, from Brazil, for association with microcephaly. |

| Mosquito lifecycle | Zika virus world map |

|---|---|

|

|

- Links: Abnormal Development - Zika Virus | Image - unlabelled virus EM | Image - labelled virus EM |WHO | PMID 26689277 | NCBI Taxonomy | Zika Genome

Prevention

Australia

The Australian Immunisation Handbook 10th edition (2015) Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health. ISBN: 978-1-74241-861-2 Online ISBN: 978-1-74241-862-9.

USA

|

For some viral infections there are antiviral medicines and immunizations (vaccines), others have no current direct protection.

In general the following public health advice is given in preventing the spread of viruses:

|

References

- ↑ Theiler RN, Wick M, Mehta R, Weaver AL, Virk A & Swift M. (2021). Pregnancy and birth outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM , 3, 100467. PMID: 34425297 DOI.

- ↑ Della Gatta AN, Rizzo R, Pilu G & Simonazzi G. (2020). COVID19 during pregnancy: a systematic review of reported cases. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , , . PMID: 32311350 DOI.

- ↑ Reyes MM, Ailes EC, Daza M, Tong VT, Osorio J, Valencia D, Turca AR, Galang RR, González Duarte M, Ricaldi JN, Anderson KN, Kamal N, Thomas JD, Villanueva J, Burkel VK, Meaney-Delman D, Gilboa SM, Honein MA, Jamieson DJ & Martinez MO. (2020). Zika Virus Detection in Amniotic Fluid and Zika-Associated Birth Defects. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , , . PMID: 31954155 DOI.

- ↑ Bokun V, Moore JJ, Moore R, Smallcombe CC, Harford TJ, Rezaee F, Esper F & Piedimonte G. (2019). Respiratory syncytial virus exhibits differential tropism for distinct human placental cell types with Hofbauer cells acting as a permissive reservoir for infection. PLoS ONE , 14, e0225767. PMID: 31790466 DOI.

- ↑ Antonson AM, Lawson MA, Caputo MP, Matt SM, Leyshon BJ & Johnson RW. (2019). Maternal viral infection causes global alterations in porcine fetal microglia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , 116, 20190-20200. PMID: 31527230 DOI.

- ↑ Zhong Z, Haltalli M, Holder B, Rice T, Donaldson B, O'Driscoll M, Le-Doare K, Kampmann B & Tregoning JS. (2019). The impact of timing of maternal influenza immunization on infant antibody levels at birth. Clin. Exp. Immunol. , 195, 139-152. PMID: 30422307 DOI.

- ↑ Ford JH, Li M, Scheil W & Roder D. (2019). Human papillomavirus infection and intrauterine growth restriction: a data-linkage study. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , 32, 279-285. PMID: 28889772 DOI.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rubinstein F, Micone P, Bonotti A, Wainer V, Schwarcz A, Augustovski F, Pichon Riviere A & Karolinski A. (2013). Influenza A/H1N1 MF59 adjuvanted vaccine in pregnant women and adverse perinatal outcomes: multicentre study. BMJ , 346, f393. PMID: 23381200

- ↑ Lai J, Fay KE & Bocchini JA. (2011). Update on childhood and adolescent immunizations: selected review of US recommendations and literature: part 2. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. , 23, 470-81. PMID: 21743328 DOI.

- ↑ Mandelbrot L. (2012). Fetal varicella - diagnosis, management, and outcome. Prenat. Diagn. , 32, 511-8. PMID: 22514124 DOI.

- ↑ Hulo C, de Castro E, Masson P, Bougueleret L, Bairoch A, Xenarios I & Le Mercier P. (2011). ViralZone: a knowledge resource to understand virus diversity. Nucleic Acids Res. , 39, D576-82. PMID: 20947564 DOI.

- ↑ False-Positive Human Immunodeficiency Virus Enzyme Immunoassay Results in Pregnant Women PMC3029371

- ↑ BMJ 2010; 341:c6580

- ↑ Rombaldi RL, Serafini EP, Mandelli J, Zimmermann E & Losquiavo KP. (2008). Transplacental transmission of Human Papillomavirus. Virol. J. , 5, 106. PMID: 18817577 DOI.

- ↑ McClure EM, Dudley DJ, Reddy UM & Goldenberg RL. (2010). Infectious causes of stillbirth: a clinical perspective. Clin Obstet Gynecol , 53, 635-45. PMID: 20661048 DOI.

- ↑ Pereira L & Maidji E. (2008). Cytomegalovirus infection in the human placenta: maternal immunity and developmentally regulated receptors on trophoblasts converge. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. , 325, 383-95. PMID: 18637517

- ↑ Plowright RK, Field HE, Smith C, Divljan A, Palmer C, Tabor G, Daszak P & Foley JE. (2008). Reproduction and nutritional stress are risk factors for Hendra virus infection in little red flying foxes (Pteropus scapulatus). Proc. Biol. Sci. , 275, 861-9. PMID: 18198149 DOI.

- ↑ Williamson MM, Hooper PT, Selleck PW, Westbury HA & Slocombe RF. (2000). Experimental hendra virus infectionin pregnant guinea-pigs and fruit Bats (Pteropus poliocephalus). J. Comp. Pathol. , 122, 201-7. PMID: 10684689 DOI.

- ↑ Hurtado CW, Golden-Mason L, Brocato M, Krull M, Narkewicz MR & Rosen HR. (2010). Innate immune function in placenta and cord blood of hepatitis C--seropositive mother-infant dyads. PLoS ONE , 5, e12232. PMID: 20814429 DOI.

- ↑ Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. (2008). Hepatitis and reproduction. Fertil. Steril. , 90, S226-35. PMID: 19007636 DOI.

- ↑ Ornoy A & Tenenbaum A. (2006). Pregnancy outcome following infections by coxsackie, echo, measles, mumps, hepatitis, polio and encephalitis viruses. Reprod. Toxicol. , 21, 446-57. PMID: 16480851 DOI.

- ↑ Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH & Gluud C. (2006). Effect of hepatitis B immunisation in newborn infants of mothers positive for hepatitis B surface antigen: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ , 332, 328-36. PMID: 16443611 DOI.

- ↑ Irving WL, James DK, Stephenson T, Laing P, Jameson C, Oxford JS, Chakraverty P, Brown DW, Boon AC & Zambon MC. (2000). Influenza virus infection in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy: a clinical and seroepidemiological study. BJOG , 107, 1282-9. PMID: 11028582

- ↑ Brankston G, Gitterman L, Hirji Z, Lemieux C & Gardam M. (2007). Transmission of influenza A in human beings. Lancet Infect Dis , 7, 257-65. PMID: 17376383 DOI.

- ↑ Chiba ME, Saito M, Suzuki N, Honda Y & Yaegashi N. (2003). Measles infection in pregnancy. J. Infect. , 47, 40-4. PMID: 12850161

- ↑ Lin WH, Kouyos RD, Adams RJ, Grenfell BT & Griffin DE. (2012). Prolonged persistence of measles virus RNA is characteristic of primary infection dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , 109, 14989-94. PMID: 22872860 DOI.

- ↑ Yun NE & Walker DH. (2012). Pathogenesis of Lassa fever. Viruses , 4, 2031-48. PMID: 23202452 DOI.

- ↑ Niklasson B, Samsioe A, Papadogiannakis N, Gustafsson S & Klitz W. (2009). Zoonotic Ljungan virus associated with central nervous system malformations in terminated pregnancy. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. , 85, 542-5. PMID: 19180651 DOI.

- ↑ Lu H, Stratton CW & Tang YW. (2020). Outbreak of Pneumonia of Unknown Etiology in Wuhan China: the Mystery and the Miracle. J. Med. Virol. , , . PMID: 31950516 DOI.

- ↑ Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, Ippolito G, Mchugh TD, Memish ZA, Drosten C, Zumla A & Petersen E. (2020). The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health - The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. , 91, 264-266. PMID: 31953166 DOI.

- ↑ Azhar EI, Hui DSC, Memish ZA, Drosten C & Zumla A. (2019). The Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. , 33, 891-905. PMID: 31668197 DOI.

- ↑ Alfaraj SH, Al-Tawfiq JA & Memish ZA. (2019). Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection during pregnancy: Report of two cases & review of the literature. J Microbiol Immunol Infect , 52, 501-503. PMID: 29907538 DOI.

- ↑ Alserehi H, Wali G, Alshukairi A & Alraddadi B. (2016). Impact of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) on pregnancy and perinatal outcome. BMC Infect. Dis. , 16, 105. PMID: 26936356 DOI.

- ↑ Gordon JW. (2002). Adenovirus gene transfer vector toxicity to mouse embryos: implications for human IVF. Hum. Reprod. , 17, 2380-7. PMID: 12202428

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (DVBD)West Nile information page viewed 11 September, 2012.

- ↑ O'Leary DR, Kuhn S, Kniss KL, Hinckley AF, Rasmussen SA, Pape WJ, Kightlinger LK, Beecham BD, Miller TK, Neitzel DF, Michaels SR, Campbell GL, Lanciotti RS & Hayes EB. (2006). Birth outcomes following West Nile Virus infection of pregnant women in the United States: 2003-2004. Pediatrics , 117, e537-45. PMID: 16510632 DOI.

- ↑ Rasmussen SA, Meaney-Delman DM, Petersen LR & Jamieson DJ. (2017). Studying the effects of emerging infections on the fetus: Experience with West Nile and Zika viruses. Birth Defects Res , 109, 363-371. PMID: 28398684 DOI.

- ↑ Pyke AT, Daly MT, Cameron JN, Moore PR, Taylor CT, Hewitson GR, Humphreys JL & Gair R. (2014). Imported zika virus infection from the cook islands into australia, 2014. PLoS Curr , 6, . PMID: 24944843 DOI.

- ↑ Kuno G & Chang GJ. (2005). Biological transmission of arboviruses: reexamination of and new insights into components, mechanisms, and unique traits as well as their evolutionary trends. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. , 18, 608-37. PMID: 16223950 DOI.

- ↑ Hamel R, Dejarnac O, Wichit S, Ekchariyawat P, Neyret A, Luplertlop N, Perera-Lecoin M, Surasombatpattana P, Talignani L, Thomas F, Cao-Lormeau VM, Choumet V, Briant L, Desprès P, Amara A, Yssel H & Missé D. (2015). Biology of Zika Virus Infection in Human Skin Cells. J. Virol. , 89, 8880-96. PMID: 26085147 DOI.

- ↑ Besnard M, Lastere S, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau V & Musso D. (2014). Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014. Euro Surveill. , 19, . PMID: 24721538

Textbooks

- Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Baron S, editor. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996.

- Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. New York: Garland Science; 2002.

Reviews

Fox KA & Theiler R. (2011). Vaccination in pregnancy. Curr Pharm Biotechnol , 12, 789-96. PMID: 21480828

Ornoy A & Tenenbaum A. (2006). Pregnancy outcome following infections by coxsackie, echo, measles, mumps, hepatitis, polio and encephalitis viruses. Reprod. Toxicol. , 21, 446-57. PMID: 16480851 DOI.

Best JM & Banatvala JE. (1990). Congenital virus infections. BMJ , 300, 1151-2. PMID: 2189514

Waterson AP. (1979). Virus infections (other than rubella) during pregnancy. Br Med J , 2, 564-6. PMID: 227524

Oberst RD. (1993). Viruses as teratogens. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. , 9, 23-31. PMID: 8384522

Articles

Pandolfi E, Chiaradia G, Moncada M, Rava L & Tozzi AE. (2009). Prevention of congenital rubella and congenital varicella in Europe. Euro Surveill. , 14, 16-20. PMID: 19317971

Horstmann DM. (1969). Viral infections in pregnancy. Yale J Biol Med , 42, 99-112. PMID: 4317516

Search Pubmed

Search Pubmed: embryo viral Infection | fetal viral Infection

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

- Australian Government The Australian Immunisation Handbook 10th Edition 2015

- Merck MMR Vaccine (PDF)

- WHO Surveillance Guidelines for Measles, Rubella and Congenital Rubella Syndrome in the WHO European Region (PDF)

- The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Abnormal Development - Viral Infection. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Viral_Infection

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G