Abnormal Development - Smoking

| Embryology - 1 Mar 2026 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| Educational Use Only - Embryology is an educational resource for learning concepts in embryological development, no clinical information is provided and content should not be used for any other purpose. |

Introduction

There is an association between physical defects among newborns and maternal smoking tobacco during pregnancy.

Spontaneous abortion, ectopic implantation, pre-term births, low-weight full-term babies, and fetal and infant deaths all occur more frequently among mothers who smoke during pregnancy than among those who do not. These developmental abnormalities are therefore environmental (maternal) in origin and not congenital (though there are probably genetics involved with a tendency to smoke).

The possible relationship to preterm birth generates one major clinical problem, as preterm birth results in 47% of all neonatal deaths (UK data).

Also of great concern is that smoking is a suggested causative factor for low infant birth weight (LBW) (2.500kg and below). LBW is in turn related to future (postnatal) health by the fetal origins hypothesis.

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Abnormal Development Smoking <pubmed limit=5>Abnormal Development Smoking</pubmed> Search term: Pregnancy Smoking <pubmed limit=5>Pregnancy Smoking</pubmed> |

| Older papers |

|---|

|

Nicotine

Nicotine is a natural ingredient in tobacco leaves, where as an alkaloid it provides some protection for the plant being eaten by insects by acting as a botanical insecticide.

Tobacco also contains other minor alkaloids nornicotine, anatabine and anabasine.

There is a chemical datasheet for nicotine, the pure chemical, note that commercial tobacco products include many additional chemicals.

Neonates have a decreased ability to metabolise nicotine, with a 3-4 times longer half-life in newborns exposed to tobacco smoke compared with adults.

Cytochrome P450, Subfamily IIA, Polypeptide 6 (CYP2A6) is the main enzyme in the liver responsible for metabolism (oxidation) of nicotine. (More? OMIM Entry CYP2A6) and there are known mutations that occur in this gene which would also impact on nicotine metabolism.

See also the recent review paper Metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Hukkanen J, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL. Pharmacol Rev. 2005 Mar;57(1):79-115. | Dempsey D, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL. Nicotine metabolism and elimination kinetics in newborns. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000 May;67(5):458-65. | OMIM Entry CYP2A6

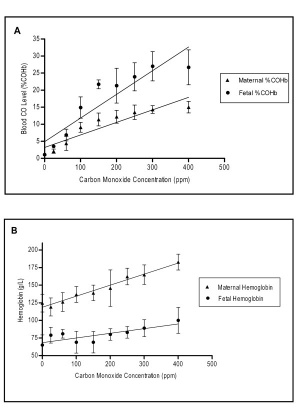

Carbon Monoxide

Smoking tobacco is also a source of carbon monoxide (CO), a colourless and odorless gas formed mainly as a by-product of incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons and can cause cytotoxicity by tissue hypoxia.

A recent study has identified in a newborn mouse model, effects on neurodevelopment of even sub-clinical levels of carbon monoxide.[12]

Carbon Monoxide:

- enters circulation though the respiratory system

- binding to haemoglobin to form carboxy-haemoglobin (COHb)

- haemoglobin affinity is 240 times greater than for oxygen

- fetal haemoglobin binds with even greater affinity

- tissue hypoxia occurs when COHb levels are greater than 70%

Epigenetics

A recent study has looked at the effect on birth weight of maternal smoking throughout pregnancy and associated epigenetic effects.[5]

- "Cigarette smoking has severe adverse health consequences in adults and in the offspring of mothers who smoke during pregnancy. One of the most widely reported effects of smoking during pregnancy is reduced birth weight which is in turn associated with chronic disease in adulthood. Epigenome-wide association studies have revealed that smokers show a characteristic "smoking methylation pattern", and recent authors have proposed that DNA methylation mediates the impact of maternal smoking on birth weight. The birthweigt of newborns whose mothers had smoked throughout pregnancy was reduced by >200g. After correction for multiple testing, 30 CpGs showed differential methylation in the maternal smoking subgroup including top "smoking methylation pattern" genes AHRR, MYO1G, GFI1, CYP1A1, and CNTNAP2. The effect of maternal smoking on birth weight was partly mediated by the methylation of cg25325512 (PIM1); cg25949550 (CNTNAP2); and cg08699196 (ITGB7). Sex-specific analyses revealed a mediating effect for cg25949550 (CNTNAP2) in male newborns."

- Links: epigenetics

Australian National Drug Strategy Household Survey 1995

Below are excerpted statistics from the 1995 household survey.

Smoking is higher among young women than young men, although males tend to smoke more heavily. Among 14-19 year olds: 13% are current regular smokers, 5% are occasional smokers, while 49% have never smoked.

For more information please email CEIDA Information Centre

Passive Smoking

Exposure of non-smokers to environmental tobacco smoke, "passive smoking", has been associated with a substantial increased disease risk (coronary heart disease, cancer) a recent study now adds diabetes to the possible deletirious effects. Houston TK, Kiefe CI, Person SD, Pletcher MJ, Liu K, Iribarren C. Active and passive smoking and development of glucose intolerance among young adults in a prospective cohort: CARDIA study. BMJ. 2006 May 6;332(7549):1064-9. "These findings support a role of both active and passive smoking in the development of glucose intolerance in young adulthood."

Smoking and Pregnancy

Smoking doubles the risk of having a low-birthweight baby and significantly increases the rate of perinatal mortality and several other adverse pregnancy outcomes. The mean reduction in birthweight for babies of smoking mothers is 200 g. High quality interventions to help pregnant women quit smoking produce an absolute difference of 8.1% in validated late-pregnancy quit rates. If abstinence is not achievable, it is likely that a 50% reduction in smoking would be the minimum necessary to benefit the health of mother and baby. Healthcare providers perform poorly in antenatal interventions to stop women smoking. Midwives deliver interventions at a higher rate than doctors. The efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy has not been established in pregnancy. Currently, its use should only be considered in women smoking more than 10 cigarettes per day who have made a recent, unsuccessful attempt to quit and who are motivated to quit. Relapse prevention programs have shown little success in the postpartum period. Data from: Quitting smoking in pregnancy Raoul A Walsh, John B Lowe, Peter J Hopkins (MJA 2001; 175: 320-323)

Placental Function

A review[13] of three placental markers showed "maternal smoking impairs human placental development by changing the balance between cytotrophoblast (CTB) proliferation and differentiation"

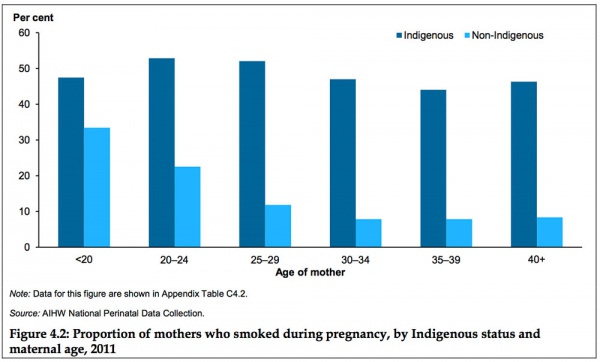

Australia

Data in this graph from AIHW 2014 Report, Birthweight of babies born to Indigenous mothers.[14]

- Links: Birth Weight

References

- ↑ Chen B, Lu KH, Ni QB, Li QX, Gao H, Wang H & Chen LB. (2019). Prenatal nicotine exposure increases osteoarthritis susceptibility in male elderly offspring rats via low-function programming of the TGFβ signaling pathway. Toxicol. Lett. , , . PMID: 31299270 DOI.

- ↑ Lavezzi AM. (2018). Toxic Effect of Cigarette Smoke on Brainstem Nicotinic Receptor Expression: Primary Cause of Sudden Unexplained Perinatal Death. Toxics , 6, . PMID: 30340403 DOI.

- ↑ McCarthy DM, Morgan TJ, Lowe SE, Williamson MJ, Spencer TJ, Biederman J & Bhide PG. (2018). Nicotine exposure of male mice produces behavioral impairment in multiple generations of descendants. PLoS Biol. , 16, e2006497. PMID: 30325916 DOI.

- ↑ Semick SA, Collado-Torres L, Markunas CA, Shin JH, Deep-Soboslay A, Tao R, Huestis MA, Bierut LJ, Maher BS, Johnson EO, Hyde TM, Weinberger DR, Hancock DB, Kleinman JE & Jaffe AE. (2018). Developmental effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on the human frontal cortex transcriptome. Mol. Psychiatry , , . PMID: 30131587 DOI.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Witt SH, Frank J, Gilles M, Lang M, Treutlein J, Streit F, Wolf IAC, Peus V, Scharnholz B, Send TS, Heilmann-Heimbach S, Sivalingam S, Dukal H, Strohmaier J, Sütterlin M, Arloth J, Laucht M, Nöthen MM, Deuschle M & Rietschel M. (2018). Impact on birth weight of maternal smoking throughout pregnancy mediated by DNA methylation. BMC Genomics , 19, 290. PMID: 29695247 DOI.

- ↑ McGrath-Morrow SA, Hayashi M, Aherrera A, Lopez A, Malinina A, Collaco JM, Neptune E, Klein JD, Winickoff JP, Breysse P, Lazarus P & Chen G. (2015). The effects of electronic cigarette emissions on systemic cotinine levels, weight and postnatal lung growth in neonatal mice. PLoS ONE , 10, e0118344. PMID: 25706869 DOI.

- ↑ Brose LS. (2014). Helping pregnant smokers to quit. BMJ , 348, g1808. PMID: 24620362

- ↑ van den Berg G, van Eijsden M, Galindo-Garre F, Vrijkotte TG & Gemke RJ. (2013). Smoking overrules many other risk factors for small for gestational age birth in less educated mothers. Early Hum. Dev. , 89, 497-501. PMID: 23578734 DOI.

- ↑ Spiegler J, Jensen R, Segerer H, Ehlers S, Kühn T, Jenke A, Gebauer C, Möller J, Orlikowsky T, Heitmann F, Boeckenholt K, Herting E & Göpel W. (2013). Influence of smoking and alcohol during pregnancy on outcome of VLBW infants. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol , 217, 215-9. PMID: 24363249 DOI.

- ↑ Taal HR, Geelhoed JJ, Steegers EA, Hofman A, Moll HA, Lequin M, van der Heijden AJ & Jaddoe VW. (2011). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and kidney volume in the offspring: the Generation R Study. Pediatr. Nephrol. , 26, 1275-83. PMID: 21617916 DOI.

- ↑ Machado Jde B, Plínio Filho VM, Petersen GO & Chatkin JM. (2011). Quantitative effects of tobacco smoking exposure on the maternal-fetal circulation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth , 11, 24. PMID: 21453488 DOI.

- ↑ Cheng Y, Thomas A, Mardini F, Bianchi SL, Tang JX, Peng J, Wei H, Eckenhoff MF, Eckenhoff RG & Levy RJ. (2012). Neurodevelopmental consequences of sub-clinical carbon monoxide exposure in newborn mice. PLoS ONE , 7, e32029. PMID: 22348142 DOI.

- ↑ Zdravkovic T, Genbacev O, McMaster MT & Fisher SJ. (2005). The adverse effects of maternal smoking on the human placenta: a review. Placenta , 26 Suppl A, S81-6. PMID: 15837073 DOI.

- ↑ AIHW 2014. Birthweight of babies born to Indigenous mothers. Cat. no. IHW 138. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 5 August 2014 http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129548202

Reviews

Jauniaux E & Burton GJ. (2007). Morphological and biological effects of maternal exposure to tobacco smoke on the feto-placental unit. Early Hum. Dev. , 83, 699-706. PMID: 17900829 DOI.

Articles

Venditti CC, Casselman R & Smith GN. (2011). Effects of chronic carbon monoxide exposure on fetal growth and development in mice. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth , 11, 101. PMID: 22168775 DOI.

Genbacev O, McMaster MT, Zdravkovic T & Fisher SJ. (2003). Disruption of oxygen-regulated responses underlies pathological changes in the placentas of women who smoke or who are passively exposed to smoke during pregnancy. Reprod. Toxicol. , 17, 509-18. PMID: 14555188

Search Pubmed

Search Pubmed: smoking and pregnancy

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2026, March 1) Embryology Abnormal Development - Smoking. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Smoking

- © Dr Mark Hill 2026, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G