Abnormal Development - Maternal Diabetes

| Embryology - 27 Feb 2026 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| Educational Use Only - Embryology is an educational resource for learning concepts in embryological development, no clinical information is provided and content should not be used for any other purpose. |

Introduction

Diabetes during pregnancy, maternal diabetes in any form, whether pregestational (type 1 or type 2) or gestational diabetes, increases the risk for adverse maternal and infant outcomes and impacts developmentally on the same systems. In the USA for the year 2000 the most frequently reported medical risk factors were: pregnancy-associated hypertension (38.8 per 1,000 live births) and diabetes (29.3) follwed by anemia (23.9).

A tenfold increase in the prevalence of hypertension and a 10 percent incidence of gestational diabetes have been reported in obese pregnant women. Women who have had gestational diabetes are much more likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Note that in some countries reporting on diabetes on birth certificates has a field that indicates whether the "mother had diabetes during pregnancy", but does not necessarily whether this was gestational or a pre-existing diabetes.

An estimated 917,000 (5.4%) Australian adults aged 18 years and over had diabetes in 2011–12, based on self-reported and measured data, from the ABS 2011–12 Australian Health Survey (Diabetes indicators, Australia 2016).

- Links: endocrine pancreas | macrosomia | Prenatal Diagnosis | Neonatal Diagnosis

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Maternal Diabetes | gestational diabetes |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

Gestational Diabetes

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as glucose intolerance with the onset or first detection during pregnancy and can occur in 2 to 17.8% of all pregnancies.

Women with gestational diabetes mellitus can progress to type 2 diabetes mellitus (progression rate 6% to 92%) have high birth weight babies and suffer birth trauma.

Well-controlled class A1 gestational diabetes (fasting blood sugar less than 105 mg/dL). Recent study shows no evidence clearly supports the practice of increased fetal surveillance in these pregnancies.

Screening and Diagnosis

The following information is based upon published Australian data. [20].

Screening should be performed at 26–28 weeks gestation (GA 26-28).

A positive screening test result is either:

- 50-gram glucose load (morning, non-fasting) with a 1-hour venous plasma glucose level of 7.8 mmol/L or over.

- 75-gram glucose load (morning, non-fasting) with a 1-hour venous plasma glucose level of 8.0 mmol/L or over.

Positive diagnosis is made based on a 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test result of either:

- fasting (0 hour) venous plasma glucose level 5.5 mmol/L or over

- 1-hour venous plasma glucose level 10.0 mmol/L or over

- 2-hour venous plasma glucose level 8.0 mmol/L or over.

Blood glucose targets for most women with gestational diabetes

| On awakening | not above 95 |

| 1 hour after a meal | not above 140 |

| 2 hours after a meal | not above 120 |

Table Data: NIDDK (NIH) - Gestational Diabetes

Gestational Diabetes Factors

Below are listed some known factors that can increase a woman’s chance of developing gestational diabetes.

- previous gestational diabetes

- previous elevated blood glucose level

- ethnicity — South and South-East Asian, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, Pacific Islander, Maori, Middle Eastern, or non-Caucasian African women are at greater risk than other women

- age — women over 40 are at greater risk than younger women

- family history of diabetes mellitus

- pre-pregnancy obesity - body mass index of more than 30 kg/m2

- previously having a high birthweight baby - greater than 4,500 grams

- polycystic ovarian syndrome

- maternal medications - including corticosteroids or antipsychotics

Australia

The Diabetes in pregnancy 2014–2015 report[21] examines the short-term impact of pre-existing diabetes (type 1 or type 2) and gestational diabetes on mothers in pregnancy and their babies between 2014 and 2015. The report analyses data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Perinatal Data Collection.

- Diabetes affects nearly 1 in 10 pregnancies - In the 2-year period from 2014–2015, more than 45,000 mothers who gave birth in Australia (excluding Victoria) had diabetes, representing about 9.9% of all births recorded in the National Perinatal Data Collection (NPDC). Of those, about 40,500 (8.9%) had gestational diabetes, and 4,700 (1.0%) had pre-existing diabetes.

- Mothers with pre-existing diabetes were at highest risk of adverse effects

- Compared with mothers with no diabetes in pregnancy, mothers with pre-existing diabetes and gestational diabetes had higher rates of caesarean section, induced labour, pre-existing and gestational hypertension, and pre-eclampsia. They also had longer antenatal and postnatal stay in hospital (5 or more days).

- Mothers with gestational diabetes experienced complications at a lower rate than mothers with pre-existing diabetes.

- Babies of mothers with pre-existing diabetes were at highest risk of adverse effects

- Compared with babies of mothers with gestational diabetes or no diabetes, babies of mothers with pre-existing diabetes had higher rates of pre-term birth, stillbirth, low and high birthweight, low Apgar score, resuscitation, and special care nursery/ neonatal intensive care unit admission, and stayed longer in hospital.

- Babies of mothers with gestational diabetes had higher rates of complications than babies of mothers with no diabetes, but showed similar levels of risk as babies of mothers with no diabetes for high birthweight and low Apgar score.

- Having diabetes in pregnancy increased the risk of complications among some population groups

- Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers, the incidence of some complications occurred at a greater rate among mothers with pre-existing diabetes than among mothers with no diabetes. Babies of Indigenous mothers with pre-existing and gestational diabetes also experienced greater rates of complications than babies of Indigenous mothers with no diabetes.

- In Remote/Very remote areas, mothers with pre-existing and gestational diabetes and their babies experienced greater rates of some complications than mothers with no diabetes and their babies.

See also Reporting Diabetes pregnancy[22]

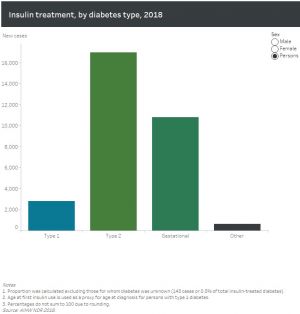

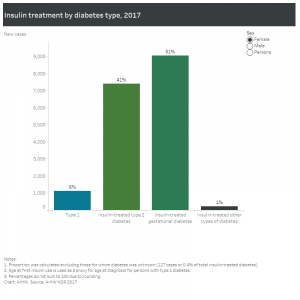

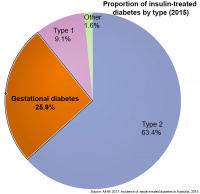

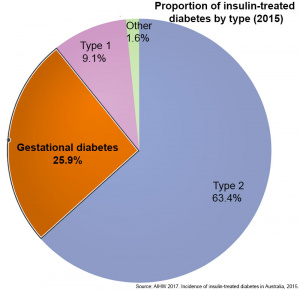

Incidence of insulin-treated diabetes in Australia, 2015

This fact sheet published in 2017[13] provides the latest available national data on new cases of insulin-treated diabetes in Australia. It shows that in 2015 there were 28,775 people who began using insulin to treat their diabetes in Australia

- 63% had type 2 diabetes

- 26% (18,142) had gestational diabetes

- 9% had type 1 diabetes

- 2% had other forms of diabetes or their diabetes status was unknown.

- Links: AIWH Factsheet

Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study

In Australia, changes to gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) diagnostic criteria have been proposed following analysis of data from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study. A recent study has looked into the effects on clinical workload of implementing these diagnostic changes.[23]

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most common antenatal complication in Western Australia. A recent study of the stage rural population[24] confirmed the association of GDM with age; obesity, lower socioeconomic quintile and Asian ethnicity are also present in the rural population.

Diabetes in pregnancy: its impact on Australian women and their babies 2010

AIHW Report[25]

- Diabetes in pregnancy is common, affecting about 1 in 20 pregnancies. Pre-existing diabetes in pregnancy affected less than 1% of pregnancies, and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affected about 5% in 2005–07.

- Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers, pre-existing diabetes affecting pregnancy was 3 to 4 times as common, and GDM twice as common, as in non-Indigenous mothers. The rate of Type 2 diabetes in Indigenous mothers was 10 times as high.

- Mothers with pre-existing diabetes were more likely to have pre-term birth, pre-term induced labour, caesarean section, hypertension and longer stay in hospital than mothers with GDM or without diabetes in pregnancy.

- Babies of mothers with pre-existing diabetes had higher rates of stillbirth, pre-term birth, high birthweight, low Apgar score, high-level resuscitation, admission to special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit, and longer stay in hospital than babies of mothers with GDM or without diabetes in pregnancy.

Gestational diabetes mellitus in Australia 2005-06

AIHW Report[26]

- 2005-06, 4.6% of women aged 15-49 years who gave birth in hospital were diagnosed with GDM (more than 12,400 women and their babies)

- 15-49 year age bracket incidence increased by over 20% between 2000-01 and 2005-06.

- Risk of being diagnosed with gestational diabetes increases with age - from 1% among 15-19 year old women to 13% among women 44-49 years of age.

- Women aged 30-34 years (age group that has the most babies) accounted for over 30% of GDM cases in 2005-06.

- Women born overseas are twice the incidence rate of women born in Australia.

- Women born in Southern Asia are at particularly high risk with an incidence rate 3.4 times the rate of Australian-born women.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women rate 1.5 times as high as other Australian women and had a higher risk across all age groups.

- Links: Diabetes in pregnancy: its impact on Australian women and their babies 2010 | AIHW Report - Gestational diabetes mellitus in Australia, 2005-06

Spain

- Trends in deliveries in women with gestational diabetes in Spain, 2001-2008.[27] "We examined trends and characteristics of deliveries in women with gestational diabetes in Spain from 2001 to 2008. There were 101,643 deliveries with gestational diabetes among 2,782,369 delivery discharges (3.6%) with no increase over time. Rate of caesarean section increased (19-24.2%) and length of stay decreased."

Diabetes

Australian trends diabetes prevalence 1990-2008

Maternal Type 1 Diabetes

Pre-pregnancy body mass index and the risk of adverse outcome in type 1 diabetic pregnancies: a population-based cohort study[28]

- risk of perinatal complications in overweight and obese women with and without type 1 diabetes (T1DM)

- based on data from the Swedish Medical Birth Registry from 1998 to 2007 (3457 T1DM and 764 498 non-diabetic pregnancies)

- High pre-pregnancy BMI is an important risk factor for adverse outcome in type 1 diabetic pregnancies.

- The combined effect of both T1DM and overweight or obesity constitutes the greatest risk. It seems prudent to strive towards normal pre-pregnancy BMI in women with T1DM.

Percentage perinatal outcomes for pregnant women with or without type 1 diabetes and stratified on pre-pregnancy BMI (Modified from Table 2[28])

| Body Mass Index | 18.5 - 24.9 | 25 - 29.9 | ≥30 |

| Large for Gestational Age | |||

|

47 | 50 | 51 |

|

8.2 | 13 | 18 |

| Major malformations | |||

|

4.0 | 3.7 | 6.6 |

|

1.7 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Pre-eclampsia | |||

|

14 | 15 | 18 |

|

2.1 | 3.3 | 5.8 |

| Preterm delivery | |||

|

20 | 23 | 23 |

|

4.5 | 4.7 | 5.7 |

| Perinatal mortality | |||

|

0.85 | 1.3 | 0.97 |

|

0.32 | 0.47 | 0.72 |

| Caesarean section | |||

|

46 | 53 | 59 |

|

13 | 17 | 22 |

| Neonatal overweight | |||

|

21 | 24 | 27 |

|

3 | 5 | 8 |

| Table Data are presented as percentages | |||

Maternal Type 2 Diabetes

A study of maternal and neonatal outcomes in 200 Korean women with or without type 2 diabetes, showed a poorer outcome with diabetes.[29] Diabetes results in a higher risk for primary caesarean section, pre-eclampsia, infections during pregnancy, large neonatal birth weight, large for gestational age, and macrosomia.

- Links: Macrosomia

Diabetic Placenta

Maternal Type 1 diabetes can alter placental vascular development. Effects may be due to either maternal hyperglycaemia or fatal hyperinsulinaemia with high glucose and insulin shown in other systems to alter vascularity, increasing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), nitric oxide (NO) and protein kinase C (PKC).[30][31]

Features of the placental vessels and villi include:

- Increased angiogenesis.

- altered junctional maturity and molecular occupancy.

- increased leakiness.

- increased surface area of the capillary wall (by elongation, enlargement of diameter).[32]

- higher branching of villous capillaries.[32]

- disruption of the stromal structure of terminal villi.[32]

In addition, a Russian histology study of placental villi in gestational diabetes and diabetes mellitus, showed greatest changes occurred in type 1 diabetes mellitus.[33]

- Links: placenta abnormalities

Diabetes Insipidus

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is a rare complication of pregnancy occurring in 1 in 30,000 pregnancies.[34]

- Central diabetes insipidus - usually damage to either the pituitary gland or hypothalamus affecting anti-diuretic hormone (ADH, vasopressin} levels.

- Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus - results from genetic or chronic abnormal kidney tubules that are unable to respond to ADH.

Drugs can cause nephrogenic diabetes (lithium and some antiviral medications).

- Gestational diabetes insipidus - vasopressinase activity secreted by placental trophoblasts destroys maternal ADH.

- Primary polydipsia cause is intake of excessive fluids.

Cardiac Effects

Maternal diabetes induces congenital heart defects in mice by altering the expression of genes involved in cardiovascular development.[35] " It is suggested that the down-regulation of genes involved in development of cardiac neural crest could contribute to the pathogenesis of maternal diabetes-induced congenital heart defects."

- Links: cardiovascular

Neural Effects

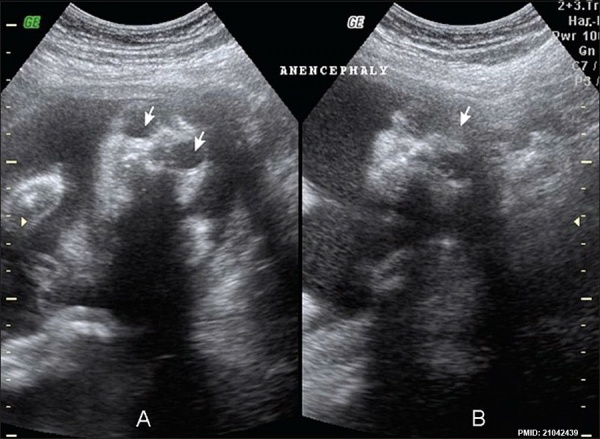

Anencephaly in a fetus (GA week 18) shown by ultrasound (coronal images) complete absence of the cranial vault and brain and enlarged orbits.[36]

- Links: Anencephaly | Neural System Development

Fetal Macrosomia

Fetal macrosomia is a clinical description for a fetus that is too large, condition increases steadily with advancing gestational age and defined by a variety of birthweights. In pregnant women, anywhere between 2 - 15% have birth weights of greater than 4000 grams (4 Kg, 8 lb 13 oz).

- Links: Birth Weight | Birth

Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity and insulin resistance cause Metabolic syndrome (MetS) that acts as a predictor for the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.

- Links: Metabolic Syndrome

Animal Models

Mouse

A recent study using a mouse diabetes model[37] has shown that suppression of glucagon action will eliminate manifestations of diabetes.

- "In conclusion, the metabolic manifestations of diabetes cannot occur without glucagon action and, once present, disappear promptly when glucagon action is abolished. Glucagon suppression should be a major therapeutic goal in diabetes."

- Links: mouse

Zebrafish

Elevated glucose induces congenital heart defects by altering the expression of tbx5, tbx20, and has2 in developing zebrafish embryos[38] "Our data demonstrate that elevated glucose alone induces cardiac defects in zebrafish embryos by altering the expression pattern of tbx5, tbx20, and has2 in the heart. We also show the first evidence that cardiac looping is affected earliest during heart organogenesis."

- Links: zebrafish

References

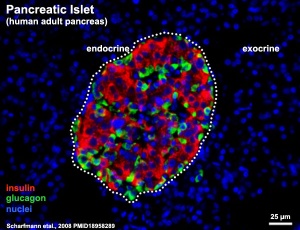

- ↑ Scharfmann R, Xiao X, Heimberg H, Mallet J & Ravassard P. (2008). Beta cells within single human islets originate from multiple progenitors. PLoS ONE , 3, e3559. PMID: 18958289 DOI.

- ↑ D'Ambrosi F, Rossi G, Soldavini CM, Di Maso M, Carbone IF, Cetera GE, Colosi E & Ferrazzi E. (2020). Ultrasound assessment of maternal adipose tissue during 1st trimester screening for aneuploidies and risk of developing gestational diabetes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand , 99, 644-650. PMID: 31898313 DOI.

- ↑ Lyu Y, Jia S, Wang S, Wang T, Tian W & Chen G. (2020). Gestational diabetes mellitus affects odontoblastic differentiation of dental papilla cells via Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in offspring. J. Cell. Physiol. , 235, 3519-3528. PMID: 31595494 DOI.

- ↑ Yu Y, Arah OA, Liew Z, Cnattingius S, Olsen J, Sørensen HT, Qin G & Li J. (2019). Maternal diabetes during pregnancy and early onset of cardiovascular disease in offspring: population based cohort study with 40 years of follow-up. BMJ , 367, l6398. PMID: 31801789 DOI.

- ↑ Wang X, Lu J, Xie W, Lu X, Liang Y, Li M, Wang Z, Huang X, Tang M, Pfaff DW, Tang YP & Yao P. (2019). Maternal diabetes induces autism-like behavior by hyperglycemia-mediated persistent oxidative stress and suppression of superoxide dismutase 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , , . PMID: 31685635 DOI.

- ↑ Blotsky AL, Rahme E, Dahhou M, Nakhla M & Dasgupta K. (2019). Gestational diabetes associated with incident diabetes in childhood and youth: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ , 191, E410-E417. PMID: 30988041 DOI.

- ↑ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019. Incidence of insulin-treated diabetes in Australia 2017. Cat. no. CDK 11. Canberra: AIHW.

- ↑ Nattero-Chávez L, Luque-Ramírez M & Escobar-Morreale HF. (2019). Systemic endocrinopathies (thyroid conditions and diabetes): impact on postnatal life of the offspring. Fertil. Steril. , 111, 1076-1091. PMID: 31155115 DOI.

- ↑ Liao Y, Xu GF, Jiang Y, Zhu H, Sun LJ, Peng R & Luo Q. (2018). Comparative proteomic analysis of maternal peripheral plasma and umbilical venous plasma from normal and gestational diabetes mellitus pregnancies. Medicine (Baltimore) , 97, e12232. PMID: 30200149 DOI.

- ↑ Lund A, Ebbing C, Rasmussen S, Kiserud TW & Kessler J. (2018). Maternal diabetes alters the development of ductus venosus shunting in the fetus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand , , . PMID: 29752712 DOI.

- ↑ Li J, Song C, Li C, Liu P, Sun Z & Yang X. (2018). Increased risk of cardiovascular disease in women with prior gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. , , . PMID: 29655653 DOI.

- ↑ Zeki R, Wang AY, Lui K, Li Z, Oats JJN, Homer CSE & Sullivan EA. (2018). Neonatal outcomes of live-born term singletons in vertex presentation born to mothers with diabetes during pregnancy by mode of birth: a New South Wales population-based retrospective cohort study. BMJ Paediatr Open , 2, e000224. PMID: 29637191 DOI.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 AIHW 2017. Incidence of insulin-treated diabetes in Australia, 2015. Diabetes series no. 27. Cat. no. CVD 78. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 20 February 2017 http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129558632.

- ↑ Zhao J, Hakvoort TBM, Ruijter JM, Jongejan A, Koster J, Swagemakers SMA, Sokolovic A & Lamers WH. (2017). Maternal diabetes causes developmental delay and death in early-somite mouse embryos. Sci Rep , 7, 11714. PMID: 28916763 DOI.

- ↑ Koo BK, Lee JH, Kim J, Jang EJ & Lee CH. (2016). Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Korea: A National Health Insurance Database Study. PLoS ONE , 11, e0153107. PMID: 27046149 DOI.

- ↑ Gürke J, Hirche F, Thieme R, Haucke E, Schindler M, Stangl GI, Fischer B & Navarrete Santos A. (2015). Maternal Diabetes Leads to Adaptation in Embryonic Amino Acid Metabolism during Early Pregnancy. PLoS ONE , 10, e0127465. PMID: 26020623 DOI.

- ↑ DeSisto CL, Kim SY & Sharma AJ. (2014). Prevalence estimates of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2007-2010. Prev Chronic Dis , 11, E104. PMID: 24945238 DOI.

- ↑ Poolsup N, Suksomboon N & Amin M. (2014). Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE , 9, e92485. PMID: 24658089 DOI.

- ↑ Chawla R, Rankin KM & Collins JW. (2014). The relation of a woman’s impaired in utero growth and association of diabetes during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J , 18, 2013-9. PMID: 24557833 DOI.

- ↑ AIHW 2010. Diabetes in pregnancy: its impact on Australian women and their babies. Diabetes series no. 14. Cat. no. CVD 52. Canberra: AIHW | PDF

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019. Diabetes in pregnancy 2014–2015. Bulletin no. 146. Cat. no. CDK 7. Canberra: AIHW.

- ↑ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018. Improving national reporting on diabetes in pregnancy: technical report. AIHW bulletin series no. 146. Cat. no. CDK 13. Canberra: AIHW.

- ↑ Flack JR, Ross GP, Ho S & McElduff A. (2010). Recommended changes to diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes: impact on workload. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol , 50, 439-43. PMID: 21039377 DOI.

- ↑ <pubmed>25171091</pubmed>

- ↑ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2010. Diabetes in pregnancy: its impact on Australian women and their babies. Diabetes series no. 14. Cat. no. CVD 52. Canberra: AIHW. AIHW | PDF

- ↑ AIHW: Templeton M & Pieris-Caldwell I 2008. Gestational diabetes mellitus in Australia, 2005–06. Diabetes series no. 10. Cat. no. CVD 44. Canberra: AIHW. AIHW Report - Gestational diabetes mellitus in Australia, 2005-06

- ↑ Lopez-de-Andres A, Carrasco-Garrido P, Gil-de-Miguel A, Hernandez-Barrera V & Jiménez-García R. (2011). Trends in deliveries in women with gestational diabetes in Spain, 2001-2008. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. , 91, e27-9. PMID: 21035890 DOI.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Persson M, Pasupathy D, Hanson U, Westgren M & Norman M. (2012). Pre-pregnancy body mass index and the risk of adverse outcome in type 1 diabetic pregnancies: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open , 2, e000601. PMID: 22334581 DOI.

- ↑ Jang HJ, Kim HS & Kim SH. (2017). Maternal and neonatal outcomes in Korean women with type 2 diabetes. Korean J. Intern. Med. , , . PMID: 28122420 DOI.

- ↑ Leach L. (2011). Placental vascular dysfunction in diabetic pregnancies: intimations of fetal cardiovascular disease?. Microcirculation , 18, 263-9. PMID: 21418381 DOI.

- ↑ Leach L, Taylor A & Sciota F. (2009). Vascular dysfunction in the diabetic placenta: causes and consequences. J. Anat. , 215, 69-76. PMID: 19563553 DOI.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Jirkovská M, Kučera T, Kaláb J, Jadrníček M, Niedobová V, Janáček J, Kubínová L, Moravcová M, Zižka Z & Krejčí V. (2012). The branching pattern of villous capillaries and structural changes of placental terminal villi in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Placenta , 33, 343-51. PMID: 22317894 DOI.

- ↑ Dubova EA, Pavlov KA, Yesayan RM, Nagovitsyna MN, Tkacheva ON, Shestakova MV & Shchegolev AI. (2011). Morphometric characteristics of placental villi in pregnant women with diabetes. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. , 151, 650-4. PMID: 22462069

- ↑ Rodrigo N & Hocking S. (2018). Transient diabetes insipidus in a post-partum woman with pre-eclampsia associated with residual placental vasopressinase activity. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep , 2018, . PMID: 29850023 DOI.

- ↑ Kumar SD, Dheen ST & Tay SS. (2007). Maternal diabetes induces congenital heart defects in mice by altering the expression of genes involved in cardiovascular development. Cardiovasc Diabetol , 6, 34. PMID: 17967198 DOI.

- ↑ Alorainy IA, Barlas NB & Al-Boukai AA. (2010). Pictorial Essay: Infants of diabetic mothers. Indian J Radiol Imaging , 20, 174-81. PMID: 21042439 DOI.

- ↑ Lee Y, Berglund ED, Wang MY, Fu X, Yu X, Charron MJ, Burgess SC & Unger RH. (2012). Metabolic manifestations of insulin deficiency do not occur without glucagon action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , 109, 14972-6. PMID: 22891336 DOI.

- ↑ Liang J, Gui Y, Wang W, Gao S, Li J & Song H. (2010). Elevated glucose induces congenital heart defects by altering the expression of tbx5, tbx20, and has2 in developing zebrafish embryos. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. , 88, 480-6. PMID: 20306498 DOI.

Journals

Reviews

Moore K, Stotz S, Fischl A, Beirne S, McNealy K, Abujaradeh H & Charron-Prochownik D. (2019). Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) in North American Indian Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA): Implications for Girls and Stopping GDM. Curr. Diab. Rep. , 19, 113. PMID: 31686243 DOI.

Vitacolonna E, Succurro E, Lapolla A, Scavini M, Bonomo M, Di Cianni G, Di Benedetto A, Napoli A, Tumminia A, Festa C, Lencioni C, Torlone E, Sesti G, Mannino D & Purrello F. (2019). Guidelines for the screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes in Italy from 2010 to 2019: critical issues and the potential for improvement. Acta Diabetol , 56, 1159-1167. PMID: 31396699 DOI.

Pergialiotis V, Bellos I, Hatziagelaki E, Antsaklis A, Loutradis D & Daskalakis G. (2019). Progestogens for the prevention of preterm birth and risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 221, 429-436.e5. PMID: 31132340 DOI.

Doi SAR, Furuya-Kanamori L, Toft E, Musa OAH, Islam N, Clark J & Thalib L. (2019). Metformin in pregnancy to avert gestational diabetes in women at high risk: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev , , . PMID: 31667980 DOI.

Ou XH, Zhu CC & Sun SC. (2019). Effects of obesity and diabetes on the epigenetic modification of mammalian gametes. J. Cell. Physiol. , 234, 7847-7855. PMID: 30536398 DOI.

Vitoratos N, Vrachnis N, Valsamakis G, Panoulis K & Creatsas G. (2010). Perinatal mortality in diabetic pregnancy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. , 1205, 94-8. PMID: 20840259 DOI.

Namak S, Lord RW, Zolotor AJ & Kramer R. (2010). Clinical inquiries: which women should we screen for gestational diabetes mellitus?. J Fam Pract , 59, 467-8. PMID: 20714459

Aleksandrov N, Audibert F, Bedard MJ, Mahone M, Goffinet F & Kadoch IJ. (2010). Gestational diabetes insipidus: a review of an underdiagnosed condition. J Obstet Gynaecol Can , 32, 225-31. PMID: 20500966

Moore TR. (2010). Fetal exposure to gestational diabetes contributes to subsequent adult metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 202, 643-9. PMID: 20430355 DOI.

Hawkins JS. (2010). Glucose monitoring during pregnancy. Curr. Diab. Rep. , 10, 229-34. PMID: 20425587 DOI.

Articles

Nicklas JM, Zera CA & Seely EW. (2020). Predictors of very early postpartum weight loss in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , 33, 120-126. PMID: 30032681 DOI.

Landon MB, Mele L, Varner MW, Casey BM, Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Rouse DJ, Tita ATN, Thorp JM, Chien EK, Saade G, Grobman W, Blackwell SC & VanDorsten JP. (2020). The relationship of maternal glycemia to childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction‡. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , 33, 33-41. PMID: 30021494 DOI.

Li P, Yin J, Zhu Y, Li S, Chen S, Sun T, Shan Z, Wang J, Shang Q, Li X, Yang W & Liu L. (2019). Association between plasma concentration of copper and gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin Nutr , 38, 2922-2927. PMID: 30661907 DOI.

Maple-Brown LJ, Brown A, Lee IL, Connors C, Oats J, McIntyre HD, Whitbread C, Moore E, Longmore D, Dent G, Corpus S, Kirkwood M, Svenson S, van Dokkum P, Chitturi S, Thomas S, Eades S, Stone M, Harris M, Inglis C, Dempsey K, Dowden M, Lynch M, Boyle J, Sayers S, Shaw J, Zimmet P & O'Dea K. (2013). Pregnancy And Neonatal Diabetes Outcomes in Remote Australia (PANDORA) Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth , 13, 221. PMID: 24289168 DOI.

França EL, Calderon Ide M, Vieira EL, Morceli G & Honorio-França AC. (2012). Transfer of maternal immunity to newborns of diabetic mothers. Clin. Dev. Immunol. , 2012, 928187. PMID: 22991568 DOI.

Alorainy IA, Barlas NB & Al-Boukai AA. (2010). Pictorial Essay: Infants of diabetic mothers. Indian J Radiol Imaging , 20, 174-81. PMID: 21042439 DOI.

Yogev Y, Melamed N, Chen R, Nassie D, Pardo J & Hod M. (2011). Glyburide in gestational diabetes--prediction of treatment failure. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , 24, 842-6. PMID: 21067291 DOI.

Fernández-Morera JL, Rodríguez-Rodero S, Menéndez-Torre E & Fraga MF. (2010). The possible role of epigenetics in gestational diabetes: cause, consequence, or both. Obstet Gynecol Int , 2010, 605163. PMID: 21052542 DOI.

van der Ploeg HP, van Poppel MN, Chey T, Bauman AE & Brown WJ. (2011). The role of pre-pregnancy physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the development of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Sci Med Sport , 14, 149-52. PMID: 21030304 DOI.

Books

- National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (UK). Diabetes in Pregnancy: Management of Diabetes and Its Complications from Preconception to the Postnatal Period. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2015 Feb. (NICE Guideline, No. 3.) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK293625/

Search Pubmed

Search Pubmed: Maternal Diabetes | Gestational Diabetes Mellitus | Gestational Diabetes | Macrosomia | Diabetic Placenta

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- Medline Plus - diabetes and pregnancy

- NIDDK (NIH) - Gestational Diabetes

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality - Gestational Diabetes: A Guide for Pregnant Women

- Australia

| Environmental Links: Introduction | low folic acid | iodine deficiency | Nutrition | Drugs | Australian Drug Categories | USA Drug Categories | thalidomide | herbal drugs | Illegal Drugs | smoking | Fetal Alcohol Syndrome | TORCH | viral infection | bacterial infection | fungal infection | zoonotic infection | toxoplasmosis | Malaria | maternal diabetes | maternal hypertension | maternal hyperthermia | Maternal Inflammation | Maternal Obesity | hypoxia | biological toxins | chemicals | heavy metals | air pollution | radiation | Prenatal Diagnosis | Neonatal Diagnosis | International Classification of Diseases | Fetal Origins Hypothesis |

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2026, February 27) Embryology Abnormal Development - Maternal Diabetes. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Maternal_Diabetes

- © Dr Mark Hill 2026, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G