Abnormal Development - Developmental Origins of Health and Disease

| Embryology - 26 Feb 2026 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Introduction

Environmental derived abnormalities relate to maternal lifestyle, environment and nutrition and while some of these directly effect embryonic development, there is also growing evidence that some effects are more subtle and relate to later life health events.

This theory, now called "developmental origins of health and disease" (DOHAD or DOHaD) and also previously Fetal Origins Hypothesis, is based on the early statistical analysis carried out by David Barker (1938 - 2013) of low birth weight data collected in the early 1900's in the south east of England which he then compared with these same babies later health outcomes. The theory was therefore originally called the "Barker Hypothesis" and has recently been renamed as "fetal origins" or "programming". Several origins have been suggested including: fetal undernutrition, endocrine (increased cortisol exposure), genetic susceptibility and accelerated postnatal growth.

More recently, discussion has occurred relating to how the data is both collected and analyzed, suggesting perhaps a smaller effect than original research suggested (see Lucas reference). Statistical methodology aside, these studies long-term periods of accurate data collection and we may have to wait some time for this research to develop.

Some research has now shifted from birth weight emphasis to that of the early postnatal infant growth. (More? Postnatal - Growth Charts)

Some Recent Findings

10th Anniversary Edition of the DOHaD Journal[2]

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Developmental Origins of Health and Disease | DoHaH | Barker Hypothesis | Fetal Origins Hypothesis |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

Barker Hypothesis

There were some key papers by David Barker that initially studied UK birth weight data that gave rise to this area of research.[11][12][13]

“The fetal origins hypothesis states that fetal undernutrition in middle to late gestation, which leads to disproportionate fetal growth, programmes later coronary heart disease.”

See also Fetal origins of adult disease-the hypothesis revisited.[14]

- The hypothesis that adult disease has fetal origins is plausible, but much supportive evidence is flawed by incomplete and incorrect statistical interpretation.

- When size in early life is related to later health outcomes only after adjustment for current size, it is probably the change in size between these points (postnatal centile crossing) rather than fetal biology that is implicated.

- Even when birth size is directly related to later outcome, some studies fail to explore whether this is partly or wholly explained by postnatal rather that prenatal factors.

- These considerations are critical to understanding the biology and timing of "programming," the direction of future research, and future public health interventions.

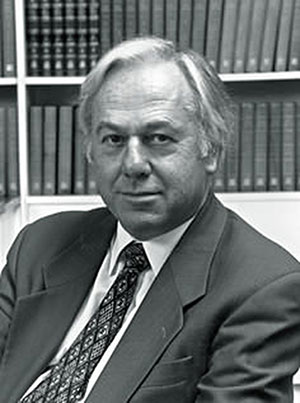

David Barker (1938 - 2013)

Professor David Barker FRS, born 29 June 1938; died 27 August 2013.

- "David Barker was one of the most influential clinical epidemiologists of our time. He challenged the idea that chronic disorders such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease are explained only by bad genes and unhealthy adult lifestyles. His 'Barker hypothesis' proposed that the fetal environment and early infant health permanently programme the body's metabolism and growth, and thus determine the pathologies of old age. Initially controversial, his ideas triggered an explosion of research worldwide into the relationship between early development and adult disease."[15]

- "David Barker received the prestigious Richard Doll Prize in 2011 given by the International Epidemiology Association (IEA). This prize is given to a person who deserved to be a candidate for the Nobel Prize but would probably not be accepted by the Nobel Committee because of the way epidemiologic research is structured and conducted. In epidemiology we can seldom point towards a specific article or even a few articles or a single person who, by himself alone, changes the way we think."[16]

- Links: memorial service

Fetal Growth Articles

Fetal growth.[17] "Recent epidemiological and experimental studies show that abnormal fetal growth can lead to serious complications, including stillbirth, perinatal morbidity and disorders extending well beyond the neonatal period. It is now clear that the intrauterine milieu is as important as genetic endowment in shaping the future health of the conceptus. Maternal characteristics such as weight, height, parity and ethnic group need to be adjusted for, and pathological factors such as smoking excluded, to establish appropriate standards and improve the distinction between what is normal and abnormal. Currently, the aetiology of growth restriction is not well understood and preventative measures are ineffective. Elective delivery remains the principal management option, which emphasizes the need for better screening techniques for the timely detection of intrauterine growth failure."

Fetal growth and long-term consequences in animal models of growth retardation.[18] "Perturbations of the maternal environment involve an abnormal intrauterine milieu for the developing fetus. The altered fuel supply (depends on substrate availability, placental transport of nutrients and uteroplacental blood flow) from mother to fetus induces alterations in the development of the fetal endocrine pancreas and adaptations of the fetal metabolism to the altered intrauterine environment, resulting in intrauterine growth retardation. The alterations induced by maternal diabetes or maternal malnutrition (protein-calorie or protein deprivation) have consequences for the offspring, persisting into adulthood and into the next generation."

Diabetes

Fetal origins of adult diabetes[7] "According to the fetal origin of adult diseases hypothesis, the intrauterine environment through developmental plasticity may permanently influence long-term health and disease. Therefore, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), due either to maternal, placental, or genetic factors, may permanently alter the endocrine-metabolic status of the fetus, driving an insulin resistance state that can promote survival at the short term but that facilitates the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in adult life, especially when the intrauterine nutrient restriction is followed by a postnatal obesogenic environment."

Perinatal Risk Factors for Diabetes in Later Life[8] "Low birth weight is consistently associated with an increased risk of non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in adulthood, but the individual contributions from poor fetal growth and preterm birth are not known. ....Our results suggest that the association between low birth weight and diabetes is due to factors associated with both poor fetal growth and short gestational age."

Renal

The Brenner hypothesis is a clinical hypothesis that states, individuals with a congenital reduction in nephron number have a much greater likelihood of developing adult hypertension and subsequent renal failure.[19] The hypothesis was developed in the 1980's by Barry Brenner a neurologist and researcher at the Brigham and Women's Hospital. This "congenital reduction" also fits with this DOHAD hypothesis.

- Links: Renal System Development | Barry Brenner

Cardiovascular

Neural Effects

The hypothesis proposes influences cause permanent changes in embryo/fetus, low birth weight, predisposition to chronic disease in adult life. Malnutrition in utero affects brain development, "low birth weight" or intrauterine growth restricted babies fare less well on measures of mental development in later life studies compared low birth weight babies (<2500 g) with controls, show impairment in neuro developmental tests up to age 11.

Intelligence is a combination of genetic and environmental influences (relative contributions of which are not yet established) and may vary over lifespan.

(Modified Text from[20] Note the commment made by Emeritus Professor P Pharaoh "One caveat that should be borne in mind, concerns the tests that are used to assess cognitive function. What do these tests actually measure? Ideally they measure innate mental ability, whatever that is, at a point in time.")

In contrast, a recent study of only postnatal growth (to 3 years of age) identified "Slower infant weight gain was not associated with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in healthy, term-born 3-year-old children."[21]

NCBI Bookshelf

Resources available from online textbooks freely available at National Library of Medicine (USA), National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Health Services/Technology Assessment Text (HSTAT)

Evidence table 5B. Studies Evaluating Association of LBW of Audiology Outcomes Part II

Birth Terms

- Premature infant - An infant born before 37 weeks of estimated gestational age

- Low birth weight - Birth weight < 2,500 g (5 lb, 8 oz)

- Very low birth weight - Birth weight < 1,500 g (3 lb, 5 oz)

- Extremely low birth weight - Birth weight < 1,000 g (2 lb, 3 oz)

References

- ↑ Hoffman DJ, Powell TL, Barrett ES & Hardy DB. (2020). Developmental Origins of Metabolic Disease. Physiol Rev , , . PMID: 33270534 DOI.

- ↑ Poston L. (2019). 10th Anniversary Edition of the DOHaD Journal. J Dev Orig Health Dis , 10, 605. PMID: 31615582 DOI.

- ↑ Safi-Stibler S & Gabory A. (2019). Epigenetics and the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease: Parental environment signalling to the epigenome, critical time windows and sculpting the adult phenotype. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. , , . PMID: 31587964 DOI.

- ↑ Chen B, Lu KH, Ni QB, Li QX, Gao H, Wang H & Chen LB. (2019). Prenatal nicotine exposure increases osteoarthritis susceptibility in male elderly offspring rats via low-function programming of the TGFβ signaling pathway. Toxicol. Lett. , , . PMID: 31299270 DOI.

- ↑ Matoso V, Bargi-Souza P, Ivanski F, Romano MA & Romano RM. (2019). Acrylamide: A review about its toxic effects in the light of Developmental Origin of Health and Disease (DOHaD) concept. Food Chem , 283, 422-430. PMID: 30722893 DOI.

- ↑ Bukowski R, Davis KE & Wilson PW. (2012). Delivery of a small for gestational age infant and greater maternal risk of ischemic heart disease. PLoS ONE , 7, e33047. PMID: 22431995 DOI.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kanaka-Gantenbein C. (2010). Fetal origins of adult diabetes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. , 1205, 99-105. PMID: 20840260 DOI.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kaijser M, Bonamy AK, Akre O, Cnattingius S, Granath F, Norman M & Ekbom A. (2009). Perinatal risk factors for diabetes in later life. Diabetes , 58, 523-6. PMID: 19066311 DOI.

- ↑ Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, Putter H, Blauw GJ, Susser ES, Slagboom PE & Lumey LH. (2008). Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , 105, 17046-9. PMID: 18955703 DOI.

- ↑ Eriksson JG. (2005). The fetal origins hypothesis--10 years on. BMJ , 330, 1096-7. PMID: 15891207 DOI.

- ↑ Barker DJ. (1990). The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ , 301, 1111. PMID: 2252919

- ↑ Barker DJ & Martyn CN. (1992). The maternal and fetal origins of cardiovascular disease. J Epidemiol Community Health , 46, 8-11. PMID: 1573367

- ↑ Barker DJ. (1997). Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in later life. Br. Med. Bull. , 53, 96-108. PMID: 9158287

- ↑ Lucas A, Fewtrell MS & Cole TJ. (1999). Fetal origins of adult disease-the hypothesis revisited. BMJ , 319, 245-9. PMID: 10417093

- ↑ Cooper C. (2013). David Barker (1938-2013). Nature , 502, 304. PMID: 24132283 DOI.

- ↑ Olsen J. (2014). David Barker (1938-2013)--a giant in reproductive epidemiology. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand , 93, 1077-80. PMID: 24628330 DOI.

- ↑ Mongelli M & Gardosi J. (2000). Fetal growth. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. , 12, 111-5. PMID: 10813572

- ↑ Holemans K, Aerts L & Van Assche FA. (1998). Fetal growth and long-term consequences in animal models of growth retardation. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. , 81, 149-56. PMID: 9989859

- ↑ Brenner BM, Garcia DL & Anderson S. (1988). Glomeruli and blood pressure. Less of one, more the other?. Am. J. Hypertens. , 1, 335-47. PMID: 3063284

- ↑ Shenkin SD, Starr JM, Pattie A, Rush MA, Whalley LJ & Deary IJ. (2001). Birth weight and cognitive function at age 11 years: the Scottish Mental Survey 1932. Arch. Dis. Child. , 85, 189-96. PMID: 11517097

- ↑ Belfort MB, Rifas-Shiman SL, Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman KP, Oken E & Gillman MW. (2008). Infant growth and child cognition at 3 years of age. Pediatrics , 122, e689-95. PMID: 18762504 DOI.

Journal

- Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease JDOHaD publishes leading research in the field of developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD), focusing on how the environment during early animal and human development, and interactions between environmental and genetic factors, influence health in later life and risk of disease. [jour PubMed listing]

- Book Developmental origins of health and disease Reviewed by R L Boon

Edited by Peter Gluckman, Mark Hanson. Published by Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006, £85.00, pp 519. ISBN 0-521-84743-5

Reviews

Calkins K & Devaskar SU. (2011). Fetal origins of adult disease. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care , 41, 158-76. PMID: 21684471 DOI.

Geelhoed JJ & Jaddoe VW. (2010). Early influences on cardiovascular and renal development. Eur. J. Epidemiol. , 25, 677-92. PMID: 20872047 DOI.

Kanaka-Gantenbein C. (2010). Fetal origins of adult diabetes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. , 1205, 99-105. PMID: 20840260 DOI.

Cota BM & Allen PJ. (2010). The developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis. Pediatr Nurs , 36, 157-67. PMID: 20687308

Tamashiro KL & Moran TH. (2010). Perinatal environment and its influences on metabolic programming of offspring. Physiol. Behav. , 100, 560-6. PMID: 20394764 DOI.

Langley-Evans SC & McMullen S. (2010). Developmental origins of adult disease. Med Princ Pract , 19, 87-98. PMID: 20134170 DOI.

Wadhwa PD, Buss C, Entringer S & Swanson JM. (2009). Developmental origins of health and disease: brief history of the approach and current focus on epigenetic mechanisms. Semin. Reprod. Med. , 27, 358-68. PMID: 19711246 DOI.

Articles

Mook-Kanamori DO, Steegers EA, Eilers PH, Raat H, Hofman A & Jaddoe VW. (2010). Risk factors and outcomes associated with first-trimester fetal growth restriction. JAMA , 303, 527-34. PMID: 20145229 DOI.

Search Pubmed

Search Pubmed: barker hypothesis | fetal origins hypothesis | fetal programming hypothesis |

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- DOHaD Society of Australia and New Zealand

- International Society for Developmental Origins of Health

- DOHaD ANZ 2016

- Meeting - DOHaD 2015

- Time Magazine - Time cover - Oct. 4, 2010

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2026, February 26) Embryology Abnormal Development - Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Developmental_Origins_of_Health_and_Disease

- © Dr Mark Hill 2026, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G