Sensory - Hearing Abnormalities

| Embryology - 13 Mar 2026 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| ICD-11 Structural developmental anomalies of the ear | |

|---|---|

| AB50 Congenital hearing impairment - Both dominant and recessive genes exist which can cause mild to profound impairment. Hearing impairment is sustained before the acquisition of language, which occurs due to a congenital condition.

LA22 Structural developmental anomalies of ear causing hearing impairment

| |

Introduction

How and why do things go wrong in development? Developing of hearing requires a complex origin, organisation, and timecourse means that abnormal development of any one system can impact upon the development of hearing. There are many different abnormalities of hearing development that can result in hearing loss and can broadly be divided into either conductive or sensorineural loss. In humans, 135 loci and 55 genes for monogenic forms of human deafness have now been identified. These abnormalities can have genetic, environmental or unknown origins. Abnormalities of the external ear, position and structure, can be used as a clinical diagnostic tool for developmental abnormalities in other systems, for example Fetal Alcohol Syndrome neural development.

In Australia, there is now an early postnatal screening of neonatal hearing as part of a NSW State Wide Infant Screening Hearing (SWISH) Program using Automated Auditory Brainstem Response (AABR).

Many environmental factors during development can lead to hearing abnormalities. A pregnancy Rubella viral infection example may cause deafness associated with congenital rubella syndrome.

| Abnormality Links: abnormal development | abnormal genetic | abnormal environmental | Unknown | teratogens | ectopic pregnancy | cardiovascular abnormalities | coelom abnormalities | endocrine abnormalities | gastrointestinal abnormalities | genital abnormalities | head abnormalities | integumentary abnormalities | musculoskeletal abnormalities | limb abnormalities | neural abnormalities | neural crest abnormalities | placenta abnormalities | renal abnormalities | respiratory abnormalities | hearing abnormalities | vision abnormalities | twinning | Developmental Origins of Health and Disease | ICD-11 | ||

|

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Abnormal Development Hearing <pubmed limit=5>Abnormal Development Hearing</pubmed> |

Inner Ear Abnormalities

Large Vestibular Aqueduct Syndrome (LVAS)

This inner ear abnormality can be one of the common causes of hearing loss.

Common cavity, severe cochlear hypoplasia

Cholesteatoma

Epithelium trapped within skull base in development, erosion of bones: temporal bone, middle ear, mastoid

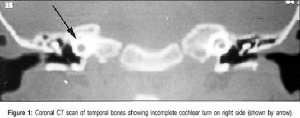

Mondini Dysplasia

(Mondini defect, Mondini malformation) Incomplete cochlea development, thought to occur during embryonic stage of growth. A common associated form of sensory neural hearing loss not associated with any known syndrome, as well as occurring as a feature of other congenital abnormalities (Turner's syndrome). Can be identified by CT scans of the head showing the cochlea region. First described by Carlo Mondini in 1791 "The Anatomic Section of a Boy Born Deaf".[7][8]

Increased risk of developing:

- recurrent meningitis

- perilymphatic fistula

- a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak due to either an enlarged cochlear aqueduct or an abnormal connection between the internal auditory canal and membranous labyrinth.

Autosomal Dominant Deafness

This form of deafness is caused by heterozygous mutation in the transmembrane cochlear-expressed gene-1 (TMC1) on chromosome 9 (9q21.13). The TMC1 protein is probably a membrane ion channel located at the tips of hair cells and required for the normal function of cochlear hair cells, it has been predicted to contain 6 transmembrane domains and to have cytoplasmic orientation of both N and C termini.

A recent study has used a mouse model of this mutation causing deafness and rescued hearing by use of gene therapy.[1] Such studies point to the future use of gene therapy for treatment of some genetic forms of deafness.

- Links: OMIM TMC1

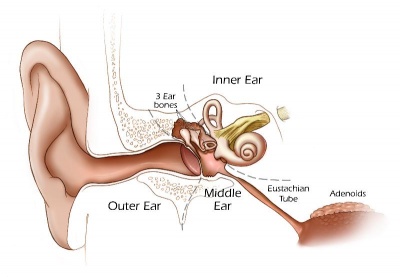

Middle Ear Abnormalities

Rare and can be part of first arch syndrome.

Fixation of the middle ear ossicles Malleus, Incus and Stapes Middle ear abnormalities (ossicular anomalies) are rare and can be part of first arch syndrome.

- familial expansile osteolysis

- malleus/incus fixation

- absence of the long process of the incus

- congenital fixation of stapes (stapes anchored to oval window)

- failure of annular ligament development

- cholesteatoma

Familial Expansile Osteolysis (FEO)

A rare congenital (autosomal dominant, 18q21.1-q22) disorder similar to Paget's disease of bone. Osteolytic lesions occur in all bones (mainly long bones) causing medullar expansions and lead eventually to middle ear and jaw abnormalities.[9]

Malleus/Incus Fixation

Congenital absence of the long process of the incus.[10]

Congenital Fixation of Stapes

In this condition the stapes is anchored to oval window often by growth of bone around the stapes (otosclerosis). Surgicallly treated by stapedectomy, where the bone and stapes is removed and replaced by a prosthesis.[11]

Cholesteatoma

Squamous epithelium that has been trapped within the skull base during development (congenital) and also occurs in an acquired form. The presence of this abnormality leads to erosion of the bones (temporal bone, middle ear, or mastoid) in which the epithelium is embedded.

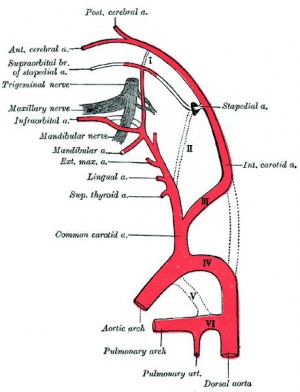

Persistent Stapedial Artery

The fetal stapedial artery initially lies between the foramen of the stapes and is lost before birth. If this regression fails, a persistent stapedial artery will affect conduction through the middle ear ossicle chain.

The condition can be seen in hemifacial microsomia (14q32), a reasonably common sporadic and rare familial autosomal dominant abnormality of the first and second pharyngeal arch derivatives.[12][13]

Chronic Otitis Media

Associated with ossicular defects, the most frequent being necrosis of the long process of incus.

Outer Ear Abnormalities

Several genetic effects and syndromes can include impacts on developmental of the external ear either directly or by altering development of the skull or face. Several developmental environment effects can be indicated by changes in the relative position or appearance of the external ear at birth. (More? Abnormal Development - Fetal Alcohol Syndrome.

- Microtia - abnormally small external ear

- Preauricular sinus - occurs in 0.25% births, bilateral (hereditary) 25-50%, unilateral (mainly the left), duct runs inward can extend into the parotid gland, Postnatally sites for infection

Microtia

The condition in humans of an abnormally small external ear is called "microtia".

This abnormality can generally be surgically repaired by use of rib cartilage to reconstruct the external ear.[14]

A recent study has identified a genetic mouse model for this condition with the knockout of the Pact gene.[15]

Preauricular Sinus

Preauricular sinus occurs in 0.25% births, is bilateral (hereditary) in 25-50% of cases and unilateral (mainly the left). They are developmental and generally occur on the surface in anterior margin of the ascending limb of the helix, and the duct runs inward to the perichondrium of the auricular cartilage and in some cases extend into the parotid gland. Postnatally they are a site for infection, mainly Staphylococcus aureus and less commonly by Streptococcus and Proteus, leading to preauricular sinus abscess.

Search PubMed: Preauricular Sinus

Links: Medline Plus - Preauricular tag or pit

Preauricular Tag

Skin tags in front of the external ear opening are common in neonates and in most cases are normal, though in some cases are indicative of other associated abnormalities.

|

|

Search PubMed: Preauricular Tag

Links: Medline Plus - Preauricular tag or pit

External Meatus Stenosis

Stenosis (narrowing) of the external auditory meatus is uncommon and can be due to chronic otitis externa or acquired atresia. The condition can be treated surgically by meatoplasty (reconstructive surgery of the canal) alone, though acquired atresia requires removal of the soft tissue plug and a split skin graft.

Search PubMed: external meatus stenosis

Congenital Deafness

Sensorineural - cochlear or central auditory pathway Conductive - disease of outer and middle ear

Sensorineural

Cochlear or central auditory pathway

- Hereditary

- recessive- severe

- dominant- mild

- can be associated with abnormal pigmentation (hair and irises)

- Acquired

- Links: Cytomegalovirus | Rubella | Drugs | Thalidomide

Conductive

Disease of outer and middle ear

- produced by otitis media with effusion, is widespread in young children.[18]

- temporary blockage of outer or middle ear

Ototoxic Medications

- Aminoglycoside antibiotics – degeneration of inner hair cells.

- Chemotherapeutic agents – cochlear metabolism toxicity

- Salicylates – cochlear metabolism toxicity (reversible).

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – cochlear metabolism toxicity (reversible).

- Quinine – cochlear metabolism toxicity.

- Loop diuretics - degeneration of inner hair cells.

- Erythromycin – possible effect on central nervous system pathways.

- Vancomycin – etiology unknown, usually enhances aminoglycocide toxicity.

Data[19]

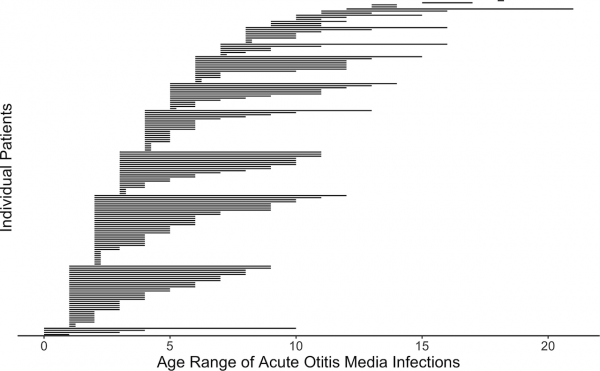

Postnatal Acute Otitis Media Infection

Postnatal growth in early childhood significantly changes the initial relationship of the middle ear and its external connection to the oral cavity. During this period the middle ear is prone to middle ear infections (acute otitis media) that can affect neural milestones in development of language. A recent study[20] has also shown that children with frequent childhood acute otitis media infections and failed otoacoustic emission (OAE) screenings later in life. See a recent review.[18]

Acute Otitis Media Infection Age

Newborn Hearing Screening

Australia

In Australia, there is now an early postnatal screening of neonatal hearing as part of a NSW State Wide Infant Screening Hearing (SWISH) Program using Automated Auditory Brainstem Response (AABR).

Links: NSW Statewide Infant Screening - Hearing (SWISH) Program

Germany

Multicenter newborn hearing screening project[3] "From the actual point of view, the "sensitive period" for the effects of hearing impairment on speech and language development is within the first year of life. Early exposure to acoustic or electric stimulation can compensate for the acoustic deficit. A regional-based, specifically designed concept of a universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS) was started in Hamburg in the year 2002. ...Sixty-three thousand, four hundred fifty-nine out of 65,466 births were registered during the period August 2002 to July 2006, 93% were primarily screened. 3.3% failed the test and 31.3% were lost to follow-up. A total of 118 children were diagnosed with hearing loss in the follow-up."

Nigeria

Very low birthweight infants and universal newborn hearing screening[21] "very low birth weight (VLBW) infants in resource-poor settings are associated with the risk of sensorineural hearing loss and other perinatal outcomes that may potentially compromise their optimal development in early childhood."

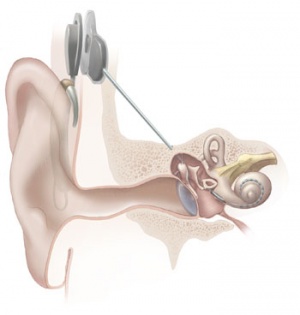

Cochlear Implant

The "Bionic Ear" was pioneered in development by Professor Graeme Clark in Australia (1960s) and first successfully used in 1978, there are now a variety of different implant devices.[22] By the year 2000 more than 13,000 children worldwide have received these implants. The medical device consists of an array of electrodes implanted within cochlea, that directly electrically stimulate the auditory nerve fibres.

The sound used to test persons with cochlear implants can be delivered by two methods, referred to as ‘‘HL’’ (hearing level) and ‘‘SPL’’ (sound pressure level), both of these methods are expressed in dB, but a specific dB HL is not the same level of loudness as the same dB SPL.

- Young children with cochlear implants compared with children with normal hearing.[23]

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

- Postion- Lower or uneven height, "railroad track” appearance, curve at top part of outer ear is under-developed, folded over parallel to curve beneath

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Askew C, Rochat C, Pan B, Asai Y, Ahmed H, Child E, Schneider BL, Aebischer P & Holt JR. (2015). Tmc gene therapy restores auditory function in deaf mice. Sci Transl Med , 7, 295ra108. PMID: 26157030 DOI.

- ↑ Gabrielli L, Bonasoni MP, Santini D, Piccirilli G, Chiereghin A, Guerra B, Landini MP, Capretti MG, Lanari M & Lazzarotto T. (2013). Human fetal inner ear involvement in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Acta Neuropathol Commun , 1, 63. PMID: 24252374 DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rohlfs AK, Wiesner T, Drews H, Müller F, Breitfuss A, Schiller R & Hess M. (2010). Interdisciplinary approach to design, performance, and quality management in a multicenter newborn hearing screening project: introduction, methods, and results of the newborn hearing screening in Hamburg (Part I). Eur. J. Pediatr. , 169, 1353-60. PMID: 20549232 DOI.

- ↑ Schrauwen I & Van Camp G. (2010). The etiology of otosclerosis: a combination of genes and environment. Laryngoscope , 120, 1195-202. PMID: 20513039 DOI.

- ↑ Poirrier AL, Van den Ackerveken P, Kim TS, Vandenbosch R, Nguyen L, Lefebvre PP & Malgrange B. (2010). Ototoxic drugs: difference in sensitivity between mice and guinea pigs. Toxicol. Lett. , 193, 41-9. PMID: 20015469 DOI.

- ↑ Shah SM, Prabhu SS & Merchant RH. (2001). Mondini defect. J Postgrad Med , 47, 272-3. PMID: 11832648

- ↑ Mondini C. Anatomia surdi nati sectio: De Bononiensi Scientiarum et Artium Institute atque Academia commentarii. Bononiae. 1791;7:419-428

- ↑ Lo WW. (1999). What is a 'Mondini' and what difference does a name make?. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol , 20, 1442-4. PMID: 10512226

- ↑ Daneshi A, Shafeghati Y, Karimi-Nejad MH, Khosravi A & Farhang F. (2005). Hereditary bilateral conductive hearing loss caused by total loss of ossicles: a report of familial expansile osteolysis. Otol. Neurotol. , 26, 237-40. PMID: 15793411

- ↑ Wehrs RE. (1999). Congenital absence of the long process of the incus. Laryngoscope , 109, 192-7. PMID: 10890764

- ↑ Seidman MD & Babu S. (2004). A new approach for malleus/incus fixation: no prosthesis necessary. Otol. Neurotol. , 25, 669-73. PMID: 15353993

- ↑ Carvalho GJ, Song CS, Vargervik K & Lalwani AK. (1999). Auditory and facial nerve dysfunction in patients with hemifacial microsomia. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. , 125, 209-12. PMID: 10037288

- ↑ Silbergleit R, Quint DJ, Mehta BA, Patel SC, Metes JJ & Noujaim SE. (2000). The persistent stapedial artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol , 21, 572-7. PMID: 10730654

- ↑ Zim SA. (2003). Microtia reconstruction: an update. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg , 11, 275-81. PMID: 14515077

- ↑ Granitzer M, Nagel W & Crabbé J. (1991). Voltage dependent membrane conductances in cultured renal distal cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta , 1069, 87-93. PMID: 1657165

- ↑ Yinon Y, Farine D & Yudin MH. (2010). Cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can , 32, 348-354. PMID: 20500943 DOI.

- ↑ Teissier N, Delezoide AL, Mas AE, Khung-Savatovsky S, Bessières B, Nardelli J, Vauloup-Fellous C, Picone O, Houhou N, Oury JF, Van Den Abbeele T, Gressens P & Adle-Biassette H. (2011). Inner ear lesions in congenital cytomegalovirus infection of human fetuses. Acta Neuropathol. , 122, 763-74. PMID: 22033878 DOI.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Vanneste P & Page C. (2019). Otitis media with effusion in children: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. A review. J Otol , 14, 33-39. PMID: 31223299 DOI.

- ↑ NSW Statewide Infant Screening - Hearing (SWISH) Program Guideline (2010) PDF

- ↑ Norowitz HL, Morello T, Kupfer HM, Kohlhoff SA & Smith-Norowitz TA. (2019). Association between otitis media infection and failed hearing screenings in children. PLoS ONE , 14, e0212777. PMID: 30794686 DOI.

- ↑ Olusanya BO. (2010). Perinatal profile of very low birthweight infants under a universal newborn hearing screening programme in a developing country: a case-control study. Dev Neurorehabil , 13, 156-63. PMID: 20450464 DOI.

- ↑ Clark GM. (2008). Personal reflections on the multichannel cochlear implant and a view of the future. J Rehabil Res Dev , 45, 651-93. PMID: 18816421

- ↑ Schramm B, Bohnert A & Keilmann A. (2010). Auditory, speech and language development in young children with cochlear implants compared with children with normal hearing. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. , 74, 812-9. PMID: 20452685 DOI.

Online Textbooks

- Clinical Methods 63. Cranial Nerves IX and X: The Glossopharyngeal and Vagus Nerves | The Tongue | 126. The Ear and Auditory System | An Overview of the Head and Neck - Ears and Hearing | Audiometry

- Health Services/Technology Assessment Text (HSTAT) Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), 2003 Oct. Developmental Disorders Associated with Failure to Thrive

- Search Bookshelf hearing development

Reviews

Vanneste P & Page C. (2019). Otitis media with effusion in children: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. A review. J Otol , 14, 33-39. PMID: 31223299 DOI.

- The International Journal of Developmental Biology Vol. 51 Nos. 6/7 (2007) Ear Development

Articles

Sennaroğlu L & Bajin MD. (2017). Classification and Current Management of Inner Ear Malformations. Balkan Med J , 34, 397-411. PMID: 28840850 DOI.

Dutton K, Abbas L, Spencer J, Brannon C, Mowbray C, Nikaido M, Kelsh RN & Whitfield TT. (2009). A zebrafish model for Waardenburg syndrome type IV reveals diverse roles for Sox10 in the otic vesicle. Dis Model Mech , 2, 68-83. PMID: 19132125 DOI.

Keefe DH, Gorga MP, Jesteadt W & Smith LM. (2008). Ear asymmetries in middle-ear, cochlear, and brainstem responses in human infants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 123, 1504-12. PMID: 18345839 DOI.

Search Pubmed

Search Pubmed: Abnormalities | Microtia | Middle ear ossicular anomalies | familial expansile osteolysis | cholesteatoma | | cochlear implant |

OMIM Database Search: Microtia

Additional Images

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- Embryo Images - Hearing

- NIDCD - Balance Disorders

- NSW Health - NSW Statewide Infant Screening - Hearing (SWISH) Program | Statewide Infant Screening - Hearing (SWISH) Program (2010 PDF

- American Academy of Audiology - American Academy of Audiology | In Memoriam: Judy Gravel

- Cochlear - Commercial Cochlear Implants | Cochlear implants for children

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2026, March 13) Embryology Sensory - Hearing Abnormalities. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Sensory_-_Hearing_Abnormalities

- © Dr Mark Hill 2026, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G