Placenta - Abnormalities

| Embryology - 9 Mar 2026 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Introduction

The placenta is a mateno-fetal organ which begins developing at implantation of the blastocyst and is delivered with the fetus at birth. As the fetus relies on the placenta for not only nutrition, but many other developmentally essential functions, the correct development of the placenta is important to correct embryonic and fetal development.

Abnormalities can range from anatomical associated with degree or site of inplantation, structure (as with twinning), to placental function, placento-maternal effects (pre-eclampsia, fetal erythroblastosis) and finally mechanical abnormalities associated with the placental (umbilical) cord.

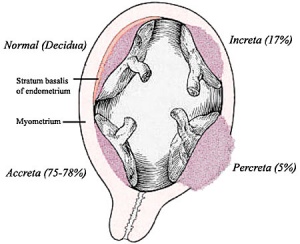

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) is the general clinical term used to describe the different forms of abnormal placental implantation (Accreta, Increta and Percreta). Clinical ultrasound indicators are the presence of an interruption of the bladder line, absence of a retroplacental clear zone, and the presence of placental lacunae.

A 2009 longitudinal Norwegian study suggests an association between large placenta relative to fetal size "disproportionately large placenta relative to birth weight was associated with increased risk of (adult) cardiovascular disease death."[1] See also the DOHAD hypothesis.

This current page lists some abnormalities associated with the placenta and also provides links to other resources. (See also Week 2 Abnormalities - Hydatidiform mole)

| System Abnormalities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Placenta Abnormalities | Placenta Previa | Placenta percreta | Placenta accreta | Placenta increta | polyhydramnios | Velamentous cord | Circumvallate Placenta | Placental Malaria |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

Placenta Shape

Placentas are generally round or oval in shape and can also be "irregular" (multilobate, "star") shapes. These irregular shaped placentas have been associated with lower birth weight for placental weight suggesting an altered function.[8]

Embryo Virtual Slides

|

Circumvallate placenta is an abnormally shaped placenta where the chorionic membranes are not inserted at the edge of the placenta, but are located inward from the margins toward the placental cord. The membranes are described as "doubled back" over the fetal surface of the placenta. |

International Classification of Diseases

| ICD-11 |

|---|

| KA02 Foetus or newborn affected by complications of placenta

KA02.0 Foetus or newborn affected by placenta praevia - Placenta praevia exists when the placenta lies wholly or in part in the lower segment of the uterus. Diagnosis has evolved from the clinical I-IV grading system, and is determined by ultrasonic imaging techniques relating the leading edge of the placenta to the cervical os. Grade I is a low lying placenta, Grade II is a placenta that meets the edge of the cervical os, Grade III is a placenta that partially covers the os, and Grade IV is a placenta that completely covers the os. KA02.1 Foetus or newborn affected by placental oedema or large placenta - A large placenta, also known as placentomegaly, is one that weighs greater than 750 g. Placentomegaly can be seen in the following conditions: fetal hydrops, maternal diabetes mellitus, Rh incompatibility, chronic infections (e.g. syphilis, cytomegalovirus), maternal anemia, or acute placental edema with acute chorioamnionitis. KA02.2 Foetus or newborn affected by placental infarction - Placental infarction is the formation of localised areas of ischemic villous necrosis, usually due to vasospasm of the maternal circulation. The affected regions of the placenta are incompetent, and lead to placental insufficiency if the infarcts are severe. KA02.3 Foetus or newborn affected by placental insufficiency or small placenta - Placental insufficiency is defined as the inability of the placenta to deliver a sufficient supply of oxygen and nutrients to the fetus, and therefore, is unable to sustain the growth of the developing baby until term. Placental insufficiency can result in intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), pre-eclampsia, abruption, or preterm labour and delivery. A small placenta is defined as a placenta that weighs less that the lower limit of normal for the gestational period. A low placental weight can be the result of a maternal condition that is causing underperfusion of the placenta, such as pre-eclampsia or maternal hypertension. A small placenta may lead to IUGR, fetal malformations, or chromosomal anomalies. KA02.4 Foetus or newborn affected by placental transfusion syndromes - Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) occurs in monozygotic twins while they are in the uterus. It occurs when blood travels from one twin to the other, and the twin that loses blood is the donor twin, while the twin that receives blood is the recipient twin. Depending on the severity of the transfusion, both infants may experience problems, such as anaemia, paleness, and dehydration in the donor twin, and redness and an increased blood pressure in the recipient twin. KA03 Foetus or newborn affected by complications of umbilical cord KA03.0 Foetus or newborn affected by prolapsed cord - A prolapsed umbilical cord is when the cord enters the opening cervix and down into the birth canal during labour before the baby has left the uterus. The risk of prolapse is higher if the baby is lying in a transverse position, the mother has had more than one baby, an excess amount of amniotic fluid exists, there is preterm prelabour rupture of membranes, or if membranes are artificially ruptured. KA03.1 Foetus or newborn affected by other compression of umbilical cord - A group of conditions characterized by findings in the fetus or newborn due obstruction of blood flow through the umbilical cord secondary to pressure from an external object or misalignment of the cord itself not classified elsewhere. LB03 Structural developmental anomalies of umbilical cord LB03.0 Allantoic duct remnants or cysts - Any condition caused by failure of the umbilical cord to correctly develop during the antenatal period. These conditions are characterized by cysts or remnants of allantoic tissue within the umbilical cord, the umbilicus, or the urachus. LB03.1 Single umbilical cord artery - A single umbilical artery arising from the either the allantoic arterial system (Type I), or vitelline artery (Type II). And has been associated with renal abnormalities. Foetus or newborn affected by abnormalities of umbilical cord length - KA03.20 Foetus or newborn affected by short umbilical cord - An umbilical cord greater than 2 SD in length below mean for the gestational age. At term, this is less than 35 cm. Often associated with fetal hypokinsesia. | KA03.21 Foetus or newborn affected by long umbilical cord - An umbilical cord greater than 2 SD in length above mean for the gestational age. At term, this is greater than 80 cm. KA03.3 Foetus or newborn affected by vasa praevia - An obstetric complication characterized by fetal vessels crossing or running in close proximity to the internal orifice of the cervix (inner cervical os). KA03.4 Foetus or newborn affected by traumatic injury of the umbilical cord

KA04.0 Foetus or newborn affected by chorioamnionitis - Chorioamnionitis is an infection of the placental tissues and amniotic fluid. It can lead to bacteremia in the mother, which is an infection of the blood, and this can cause preterm birth or infection in the newborn. Organisms which are usually responsible for chorioamnionitis include Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Group B streptococcus. KA04.1 Foetus or newborn affected by amniotic Band Syndrome KA80.2 Foetal blood loss from placenta Maternal JA8A Maternal care related to placental disorders - JA8A.0 Placental transfusion syndromes | JA8A.1 Malformation of placenta | JA8A.2 Morbidly adherent placenta JA8B Maternal care related to placenta praevia or low lying placenta - JA8B.0 Placenta praevia specified as without haemorrhage | JA8B.1 Placenta praevia with haemorrhage JA8C Maternal care related to premature separation of placenta JB0B.0 Retained placenta without haemorrhage - A condition characterized by a placenta that has not been expelled from the uterus during the third stage of labour and up to 30 minutes following delivery, and without haemorrhage. This condition is caused by uterine atony, a trapped placenta, or a placenta accreta. This condition may lead to primary postpartum haemorrhage or infection. JA8A.2 Morbidly adherent placenta JA43.0 Third-stage haemorrhage - A condition characterized by excessive loss of blood during the third stage of labour for a vaginal delivery. This condition is caused by uterine atony, trauma, retained placenta, or coagulopathy. |

| placenta abnormalities | ICD-11 |

Placenta Weight

A recent Canadian study of 87,600 singleton births[9] has identified a number of risk factors for both high and low placental weight. Some factors are associated either before, after or both accounting for birthweight.

Low placental weight

- chronic hypertension (before and after accounting for birthweight).

- pre-eclampsia (before, but not after adjustment for birthweight).

High placental weight

- anaemia (before and after adjustment for birthweight).

- gestational diabetes (before and after adjustment for birthweight).

- smoking (after adjustment for birthweight).

- Placental and cord determinants include chorioamnionitis, chorangioma/chorangiosis, circumvallate placenta and marginal cord insertion.

Morbidly Adherent Placenta

| ICD-11 JA8A.2 Morbidly adherent placenta |

Placenta Accreta

The term placenta accreta refers to abnormal adherence, with absence of decidua basalis. The incidence of placenta accreta also significantly increases in women with previous cesarean section compared to those without a prior surgical delivery.[11][12] Detection bu ultrasound in the first trimester has low sensitivity (41%), that increases in the second trimester (60%) and third trimester (83,5%}.[13]

Ultrasound features:[14]

- Deficiency of retroplacental sonolucent zone

- Vascular lacunae

- Myometrial thinning

- Interruption of bladder line

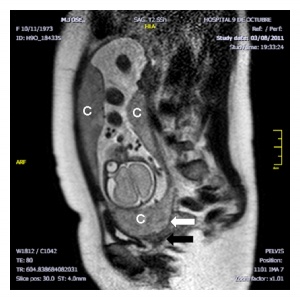

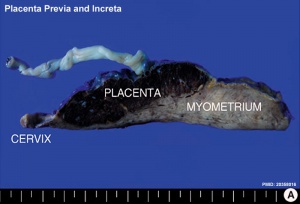

Placenta Increta

| Placenta Increta occurs when the placenta attaches deep into the uterine wall and penetrates into the uterine muscle, but does not penetrate the uterine serosa.

|

Placenta Increta and Previa[15] |

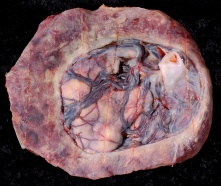

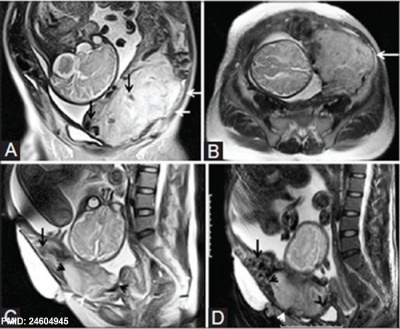

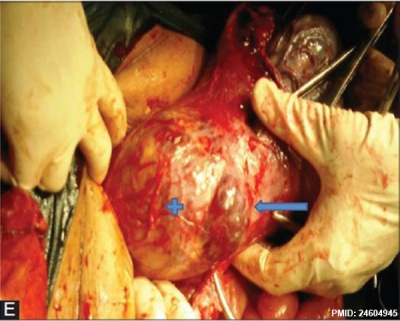

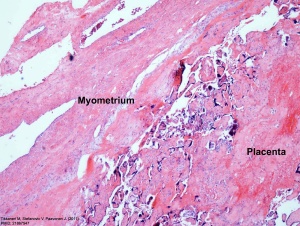

Placenta Percreta

In placenta percreta the placental villi penetrate the myometrium and through to uterine serosa.

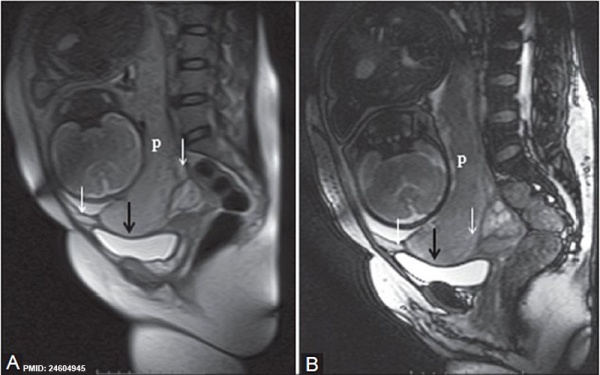

| MRI | Surgery |

|---|---|

|

|

| Placenta Percreta MRI[16] | Surgical photograph Showing the placenta extending through uterine wall (+) and covered by thin serosal layer (arrow), no features of bladder invasion. |

| Placental villi penetrate myometrium and through to uterine serosa.

See clinical article on the laparoscopic management of placenta percreta. [17] |

Placenta Percreta Histopathology[18] |

Placenta Previa

| ICD-11 KA02.0 Foetus or newborn affected by placenta praevia - Placenta praevia exists when the placenta lies wholly or in part in the lower segment of the uterus. Diagnosis has evolved from the clinical I-IV grading system, and is determined by ultrasonic imaging techniques relating the leading edge of the placenta to the cervical os. Grade I is a low lying placenta, Grade II is a placenta that meets the edge of the cervical os, Grade III is a placenta that partially covers the os, and Grade IV is a placenta that completely covers the os. |

Historically, Paul Portal (1630-1703), a French physician[19], was the first to describe in 1685 a case of placenta previa in his "The Compleat Practice of Men and Women Midwives".

In this placental abnormality, the placenta overlies internal cervical os of uterus, essentially covering the birth canal. In the third trimester and at term, abnormal bleeding can require caesarian delivery and can also lead to abruptio placenta. This condition occurs in approximately 1 in 200 to 250 pregnancies and risk factors include prior cesarean delivery, pregnancy termination, intrauterine surgery, smoking, multifetal gestation, increasing parity, and maternal age. Ultrasound screening programs during 1st and early 2nd trimester pregnancies now include placental localization. Diagnosis can also be made by transvaginal ultrasound.

A retrospective study of from 59,149 women of 724 pregnancies (1.2%) diagnosed with a complete or partial previa, identified no associated with fetal growth restriction.[20]

A more recent retrospective study from 678 cases of placenta previa did not show differences depending on the type of placentation, but in the site of placentation.[3]

- Anterior wall - associated with shorter gestational age, low birth weight, lower Apgar score, higher prenatal bleeding rate, increased postpartum hemorrhage, longer duration of hospitalization, and higher blood transfusion and hysterectomy rates compared to cases with lateral/posterior wall placenta.

- Previous cesarean incision site - increased the incidence of complete placenta previa and PAS disorders compared with placental attachment at a site without incision, but did not significantly influence pregnancy outcomes.

Placenta previa does not appear to be affected by maternal age for maternal/neonatal outcomes.[21]

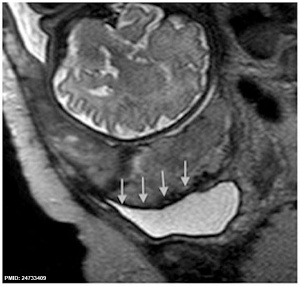

Placenta previa MRI[16]

A 2007 Canadian study[22] identified that following first live birth delivery by caesarean section there is a 47% increased risk of placenta praevia and 40% increased risk of placental abruption in the second pregnancy with a singleton.

See also recent advances in the management of placenta previa. [23][12]

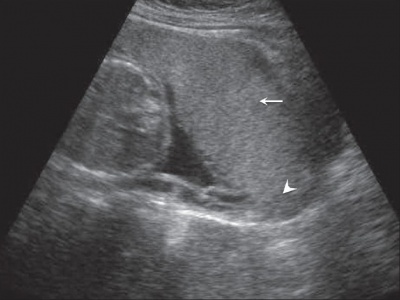

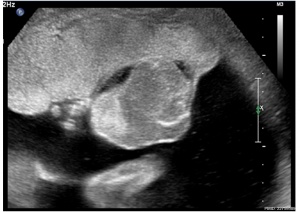

Ultrasound Placenta Previa

|

|

| Anterior placenta position (upper arrow) in relation to cervix os (lower arrow). | Posterior placenta position (arrow) in relation to cervix os (triangle). |

|

Placental tissue is seen on the anterior and posterior uterine wall and completely covers the cervix. |

- Links: Ultrasound

Vasa Previa

| ICD-11 KA03.3 Foetus or newborn affected by vasa praevia - An obstetric complication characterized by fetal vessels crossing or running in close proximity to the internal orifice of the cervix (inner cervical os). |

| Vasa previa (vasa praevia) placental abnormality where the fetal vessels lie within the membranes close too or crossing the inner cervical os (opening) and generally diagnosed (98%) by ultrasound. This occurs normally in 1:2500-5000 pregnancies and leads to complications similar too those for placenta previa.[12] Approximately 28% of prenatally diagnosis cases result in emergent preterm delivery.[24]

Type II is defined as the condition where the fetal vessels are found crossing over the internal os connecting either a bilobed placenta or a succenturiate lobe with the main placental mass.[25] There are suggestions that colour doppler ultrasound can be used to visualise the blood vessels in high-risk cases and if required elective caesarean performed at 35–36 weeks in cases diagnosed as vasa praevia.[26] Two main associations:

Some recent evidence of successful in utero laser ablation of type II vasa previa at 22.5 weeks of gestation. |

Vasa previa ultrasound movie |

Management of vasa previa

The following text is from a recent paper identifying the Canadian guidelines for the management of vasa previa.[27]

- If the placenta is found to be low lying at the routine second trimester ultrasound examination, further evaluation for placental cord insertion should be performed. (II-2B)

- Transvaginal ultrasound may be considered for all women at high risk for vasa previa, including those with low or velamentous insertion of the cord, bilobate or succenturiate placenta, or for those having vaginal bleeding, in order to evaluate the internal cervical os. (II-2B)

- If vasa previa is suspected, transvaginal ultrasound colour Doppler may be used to facilitate the diagnosis. Even with the use of transvaginal ultrasound colour Doppler, vasa previa may be missed. (II-2B)

- When vasa previa is diagnosed antenatally, an elective Caesarean section should be offered prior to the onset of labour. (II-1A)

- In cases of vasa previa, premature delivery is most likely; therefore, consideration should be given to administration of corticosteroids at 28 to 32 weeks to promote fetal lung maturation and to hospitalization at about 30 to 32 weeks. (II-2B)

- In a woman with an antenatal diagnosis of vasa previa, when there has been bleeding or premature rupture of membranes, the woman should be offered delivery in a birthing unit with continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring and, if time permits, a rapid biochemical test for fetal hemoglobin, to be done as soon as possible; if any of the above tests are abnormal, an urgent Caesarean section should be performed. (III-B

- Women admitted with diagnosed vasa previa should ideally be transferred for delivery in a tertiary facility where a pediatrician and blood for neonatal transfusion are immediately available in case aggressive resuscitation of the neonate is necessary. (II-3B)

- Women admitted to a tertiary care unit with a diagnosis of vasa previa should have this diagnosis clearly identified on the chart, and all health care providers should be made aware of the potential need for immediate delivery by Caesarean section if vaginal bleeding occurs. (III-B).

Abruptio Placenta

Represents interruption of the placenta by partial or complete separation, retroplacental blood clot formation and abnormal hemorrhage prior to delivery. There is significant perinatal mortality associated with abruptio placenta.[28]

Placenta Variants

Bilobed Placenta

Placenta with two equal-sized lobes connected by a thin bridge. No identified risks of this structure.

Circumvallate placenta

Chorionic plate smaller than basal plate, edges rolled. Placental abruption and haemorrhage risks.

Placenta Membranacea

A rare placental abnormality where either all (diffuse placenta membranacea) or part (partial placenta membranacea) is covered by chorionic villi (placental cotyledons). Clinically the abnormality presents with vaginal bleeding, in the second or third trimester or during labor, due to an associated placenta previa.[29] Ultrasound has been used to detect this condition.[30]

- Links: Search PubMed | Ultrasound

Succenturiate Placenta

Additional lobule separate from the main part of placenta. Risk of vessel rupture and placenta retention.

- Links: Search PubMed | Ultrasound

Battledore Placenta

Placenta battledore (batyldoure = a beating instrument) is a term describing a placenta where the umbilical cord is attached at the margin. Occurs 7- 9% in singleton pregnancies and 24-33% in twin pregnancies and may effect placental function/fetal growth. The description probably comes from the similarity to a bat or paddle.

- Links: Search PubMed | Ultrasound

Chronic Intervillositis

(massive chronicintervillositis, chronic histiocytic intervillositis) Rare placental abnormality and pathology defined by inflammatory placental lesions, mainly in the intervillous space (IVS), with a maternal infiltrate of mononuclear cells (monocytes, lymphocytes, histiocytes) and intervillous fibrinoid deposition.[31]

- Links: Search PubMed | Ultrasound

Placental Mesenchymal Dysplasia

Due to a similar "grape-like" placental appearance, this rare disorder placental mesenchymal stem villous hyperplasia has been mistaken both clinically and macroscopically for a partial hydatidiform molar pregnancy. The disorder also has a high incidence of both intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and fetal death.[32] The placental abnormality may be detected, but difficult to diagnose, by ultrasound.[33]

Current research suggests that placental cells may be originated from a mixed population of androgenetic (paternal-derived genome only) and biparental cells.[34] This means that chorionic villus sampling can provide a differential diagnosis between this and a partial mole.[35]

Pre-eclampsia

This condition is also known as gestational proteinuric hypertension and occurs in occurs in approximately 2 to 4% of all pregnancies. The pathogenesis of eclamptic convulsions remains unknown and women with a history of eclampsia are at increased risk of eclampsia (1-2%) and preeclampsia (22-35%) in subsequent pregnancies. "Magnesium sulfate is the drug of choice for reducing the rate of eclampsia developing intrapartum and immediately postpartum."(see Sibai BM. 2005).

Recent research using a large population study in Norway has shown a strong generational association such that daughters of women who had pre-eclampsia during pregnancy had more than twice the risk of pre-eclampsia themselves. The paper concludes "Maternal genes and fetal genes from either the mother or father may trigger pre-eclampsia. The maternal association is stronger than the fetal association. The familial association predicts more severe pre-eclampsia."[36]

Diabetic Placenta

Maternal Type 1 diabetes can alter placental vascular development. Effects may be due to either maternal hyperglycaemia or fatal hyperinsulinaemia with high glucose and insulin shown in other systems to alter vascularity, increasing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), nitric oxide (NO) and protein kinase C (PKC).[37][38]

Features of the placental vessels include:

- Increased angiogenesis

- altered junctional maturity and molecular occupancy

- increased leakiness

The placental terminal villi also show vascularity changes including both hypovascularity and hypervascularity. A recent study of the normal and diabetic placenta,[6] shows the diabetic placenta terminal villi were:

- hypovascular villi - had a smaller diameter and a wavy course

- hypervascular villi - had numerous capillaries, reduced stroma and were large in diameter.

Specific changes included:

- villous stroma - collagen envelope around capillaries looked thinner and the network of collagen fibers seemed less dense.

- stromal cells - loss of desmin filaments.

- villous capillaries - were more branched.

- Links: Maternal Diabetes

Placental Chorioangioma

Chorioangiomas are the most common tumour of the placenta, occurring in approximately 1 % of all placentas and are generally benign vascular tumours (haemangiomas).

- Small chorioangiomas are generally not clinically significant and usually found incidentally.

- Large chorioangiomas have been associated with a range of fetal conditions (fetal anemia, thrombocytopenia, hydrops, hydramnios, intrauterine growth retardation) including prematurity and stillbirth.

| Placental Chorioangioma Ultrasound | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Ultrasound scan placenta and chorioangioma | Ultrasound blood flow in chorioangioma |

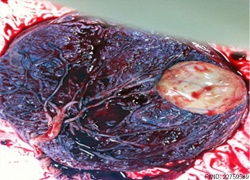

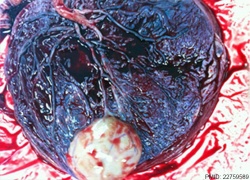

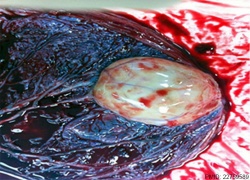

| Placental Chorioangioma | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Example of a placental chorioangioma forming a yellowish, well-circumscribed firm mass (5 cm × 5 cm) connected by two vessels to the placenta. Histopathologic examination revealed a placental disc 15 cm × 17 cm × 13 cm, with a three-vessel umbilical cord that was attached peripherally and measured 9 cm × 1.5 cm. The weight of the placenta was 530 g. The tumor was confirmed to be a chorioangioma.[39]

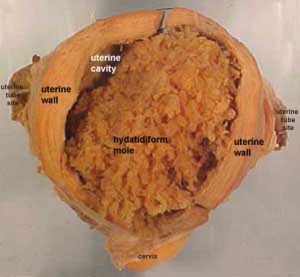

Hydatidiform Mole

Another type of abnormality is when only the conceptus trophoblast layers proliferates and not the embryoblast, no embryo develops, this is called a "hydatidiform mole" (HM), which is due to the continuing presence of the trophoblastic layer, this abnormal conceptus can also implant in the uterus. The trophoblast cells will secrete human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), as in a normal pregnancy, and may appear maternally and by pregnancy test to be "normal". Prenatal diagnosis by ultrasound analysis demonstrates the absence of a embryo.

There are several forms of hydatidiform mole: partial mole, complete mole and persistent gestational trophoblastic tumor. Many of these tumours arise from a haploid sperm fertilizing an egg without a female pronucleus (the alternative form, an embryo without sperm contribution, is called parthenogenesis). The tumour has a "grape-like" placental appearance without enclosed embryo formation. Following a first molar pregnancy, there is approximately a 1% risk of a second molar pregnancy.

- The incidence of hydatidiform mole varies between ethnic groups, and typically occurs in 1 in every 1500 pregnancies.

- All hydatidiform mole cases are sporadic, except for extremely rare familial cases.

- A maternal gene has been identified for recurrent hydatidiform mole (chromosome 19q13.3-13.4 in a 15.2 cM interval flanked by D19S924 and D19S890).[40]

- Links: Hydatidiform Mole | Week 2 - Abnormalities

Mole Types

Complete mole - chromosomal genetic material from the ovum (egg) is lost, by an unknown process. Fertilization then occurs with one or two sperm and an androgenic (from the male only) conceptus (fertilized egg) is formed. With this conceptus the embryo (fetus, baby) does not develop at all but the placenta does grow but it is abnormal and forms lots of cysts and has no blood vessels. These cysts look like a cluster of grapes and that is why it is called a hydatidiform mole (grape like). A hydatidiform mole miscarries by about 16 to 18 weeks gestational age. Since the diagnosis can be made by ultrasound before that time, it is better for you to have an evacuation of the uterus (D & C) so that there is no undue bleeding and no infection. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) will assist in making the diagnosis.

Partial mole - three sets of chromosomes instead of the usual two and this is called triploidy. With such a pregnancy the chromosomal (genetic) material from the ovum (egg) is retained and the egg is fertilized by one or two sperm. Since with partial mole there are maternal chromosomes there is a fetus but because of the three sets of chromosomes this fetus is always grossly abnormal and will not survive. (Text modified from: International Society for the Study of Trophoblastic Diseases,see also JRM Gestational Trophoblastic Disease)

Tumour Growth

Like any tumour, unless removed there is a risk of progression:

- Stage I: Tumor confined to uterus (non-metastatic)

- Stage II: Tumor involving pelvic organs and/or vagina

- Stage III: Tumor involving lungs, with or without involving pelvic structures and/or vagina

- Stage IV: Tumor involving distant organs

Placental Mesenchymal Dysplasia

Due to a similar "grape-like" placental appearance, this rare disorder has been mistaken both clinically and macroscopically for a partial hydatidiform molar pregnancy. This disorder also has a high incidence of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and fetal death.

Twin Pregnancy Mole

Hydatidiform mole and co-existent healthy fetus is a very rare condition with only 30 cases documented in detail in the literature.[41]

- Links: International Society for the Study of Trophoblastic Diseases | Sydney Gynaecological Oncology Group Gestational Trophoblastic Disease | The Journal of Reproductive Medicine Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (1998) | Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Gynecologic Oncology Program

Cord Abnormalities

ICD-11 Foetus or newborn affected by abnormalities of umbilical cord length - KA03.20 Foetus or newborn affected by short umbilical cord

LB03.1 Single umbilical cord artery - A single umbilical artery arising from the either the allantoic arterial system (Type I), or vitelline artery (Type II). And has been associated with renal abnormalities. LB03.0 Allantoic duct remnants or cysts - Any condition caused by failure of the umbilical cord to correctly develop during the antenatal period. These conditions are characterized by cysts or remnants of allantoic tissue within the umbilical cord, the umbilicus, or the urachus. |

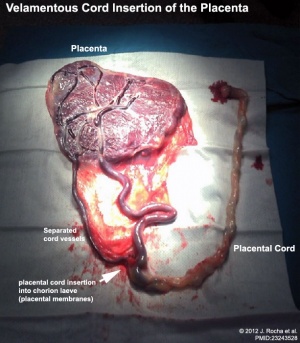

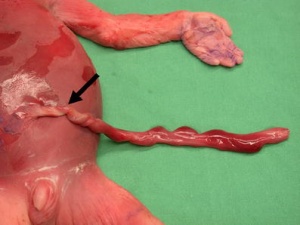

Velamentous Cord Insertion

(velamentous insertion) Clinical term for describing a placental abnormality where the placental cord inserts into the chorion laeve (placental membranes) away from the edge of the placenta. The placental vessels can also diverge as they traverse between the amnion and chorion before reaching the placenta.The placental vessels are therefore unprotected by Wharton's jelly where they traverse the membranes before they come together into the umbilical cord. This can cause hemorrhage if the vessels are damaged when the membranes are ruptured prior to birth. The condition is more common in monozygotic twins (15%) and triplets.

Velamentous cord insertion, with a low uterine body implantation site, has also been shown to affect fetal heart rate.[43]

A bilobed placenta with velamentous cord insertion.

Cord Vessel Number

|

| Cord with one artery and one vein |

Persistent Right Umbilical Vein

A fairly rare anomaly, a study of 15,237 obstetric ultrasound examinations performed after 15 weeks' gestation identified only 33 cases of persistent right umbilical vein.[44] Some studies have identified associated fetal anomalies with this condition[45], including cardiac abnormalities.[46]

A recent human embryo study of persistent right umbilical vein[47] identified 2 specimens:

- a specimen with a degenerating right umbilical vein (UV) joined the thick left UV in a narrow peritoneal space between the liver and abdominal cavity

- another specimen with a degenerating left UV joined a thick right UV in the abdominal wall near the liver.

In both specimens, the umbilical vein drained into the normal, umbilical portion of the left liver.

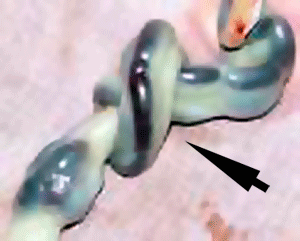

Cord Knotting

| There are few abnormalities associated with umbilical cord development, other that abnormally short or long cords, which in most cases do not cause difficulties.

In some cases though, long cords can wrap around limbs or the fetus neck, which can then restrict blood flow or lead to tissue or nerve damage, and therefore effect develoment. Cord knotting can also occur (1%) in most cases these knots have no effect, in some cases of severe knotting this can prevents the passage of placental blood. |

Umbilical cord torsion

|

Rare umbilical cord torsion, even without knot formation can also affect placental blood flow, even leading to fetal demise.[48] |

Cord Length

Furcate cord

Refers to the separation of placental vessels before their attachment into the placenta.[49]

Fetal Erythroblastosis

This disease is also called Haemolytic Disease of the Newborn, an immune problem from fetus Rh+ /maternal Rh-, leakage from fetus causes anti-Rh antibodies, which is then dangerous for a 2nd child.

RHESUS BLOOD GROUP

Placental Infections

Several infective agents may cross into the placenta from the maternal circulation, as well as enter the embry/fetal circulation. The variety of bacterial infections that can occur during pregnancy is as variable as the potential developmental effects, from virtually insignificant to a major developmental, abortive or fatal in outcome.

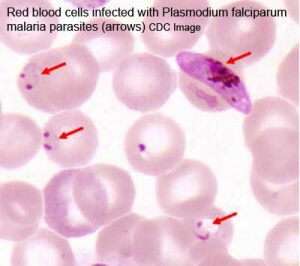

Placental Malaria

Pregnant women have an increased susceptibility to malaria infection. Malarial infection of the placenta by sequestration of the infected red blood cells leading to low birth weight and other effects. There are four types of malaria caused by the protozoan parasite Plasmodium falciparum (main), Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium malariae). This condition is common in regions where malaria is endemic with women carrying their first pregnancy (primigravida).

- Links: malaria

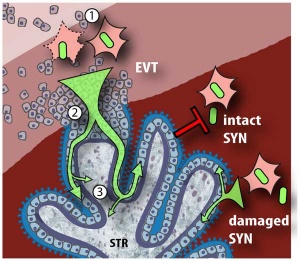

Placental Herpesvirus

A recent paper has identified using an in vitro model that human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) can infect the placenta[50]

Cytomegalovirus Placentitis

Clinical term for the cytomegalovirus infection of the placenta.

A earlier histological study[51] identified fixed connective tissue cells predominantly infected cell type in placental tissue. In addition, endothelial cells, macrophages and in some cases trophoblast infection. While a more recent in vitro study[52] suggests that all villi cell types are likely to be infected.

- Links: cytomegalovirus | viral infection

Leishmania Infection

Very little is known about the tropical disease caused by parasites of the genus Leishmania, agents of tegumentary leishmaniasis (TL) and visceral leishmaniasis (VL, kala-azar, black fever, Dumdum fever). Though there is similar to malaria, placental infection and transplacental transmission of this parasite. [53][54]

- Search PubMed: Placental Leishmania

Placental Membranes

There are few documented abnormalities associated with feral membranes (chorion, amnion). Ultrasound measurement of abnormal yolk sac size/shape in early embryonic development has been suggested as an indicator of early gestational loss. The most common literature described abnormalities are those associated with abnormal vasularization of the chorion.

Chorioamnionitis

ICD Code: O41.1 Infection of amniotic sac and membranes Amnionitis Chorioamnionitis Membranitis Placentitis

The best known environmental effect is infection of chorion and/or amnion referred to as chorioamnionitis.[55]

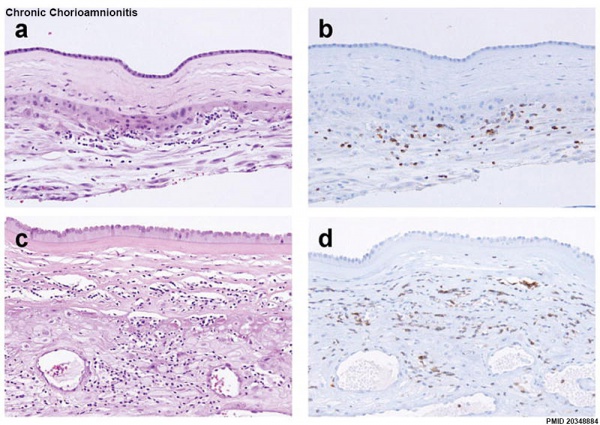

Chronic Chorioamnionitis Histology[56]

- Stage 1 ((a, b) inflammation showing infiltration of lymphocytes limited to the chorionic trophoblast layer (a). CD3 immunostaining demonstrates that the majority of these cells are T cells (b).

- Stage 2 (c, d) inflammation is characterized by infiltration of lymphocytes into the chorioamniotic connective tissue layer ((Stain - Haematoxylin Eosin), c), which are largely CD3+ T cells (d).

- Links: Bacterial Infection | Placental Membranes

Placental Pathology

The following pathology information from a clinical paper.[57]

Chronic Villitis

This condition can occur following placental infection leading to maternal inflammation of the villous stroma, often with associated intervillositis. The inflammation can lead to disruption of blood flow and necrotic cell death.

Massive Chronic Intervillositis

(MCI) The maternal blood-filled space is filled with CD68-positive histiocytes and an increase in fibrin, occuring more commonly in the first trimester.

Meconium Myonecrosis

The prolonged meconium exposure leads to toxic death of myocytes of placental vessels (umbilical cord or chorionic plate).

Neuroblastoma

A fetal malignancy that leads to an enlarged placenta, with tumor cells in the fetal circulation and rarely in the chorionic villi.

Thrombophilias

(protein C or S deficiency, factor V Leiden, sickle cell disease, antiphospholipid antibody) This condition can generate an increased fibrin/fibrinoid deposition in the maternal or intervillous space, this can trap and kill villi.

References

- ↑ Risnes KR, Romundstad PR, Nilsen TI, Eskild A & Vatten LJ. (2009). Placental weight relative to birth weight and long-term cardiovascular mortality: findings from a cohort of 31,307 men and women. Am. J. Epidemiol. , 170, 622-31. PMID: 19638481 DOI.

- ↑ Heerema-McKenney A. (2018). Defense and infection of the human placenta. APMIS , 126, 570-588. PMID: 30129129 DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jing L, Wei G, Mengfan S & Yanyan H. (2018). Effect of site of placentation on pregnancy outcomes in patients with placenta previa. PLoS ONE , 13, e0200252. PMID: 30016336 DOI.

- ↑ Wortman AC, Schaefer SL, McIntire DD, Sheffield JS & Twickler DM. (2018). Complete Placenta Previa: Ultrasound Biometry and Surgical Outcomes. AJP Rep , 8, e74-e78. PMID: 29686936 DOI.

- ↑ Nasiell J, Papadogiannakis N, Löf E, Elofsson F & Hallberg B. (2016). Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in newborns linked to placental and umbilical cord abnormalities. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , 29, 721-6. PMID: 25714479 DOI.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jirkovská M, Kučera T, Kaláb J, Jadrníček M, Niedobová V, Janáček J, Kubínová L, Moravcová M, Zižka Z & Krejčí V. (2012). The branching pattern of villous capillaries and structural changes of placental terminal villi in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Placenta , 33, 343-51. PMID: 22317894 DOI.

- ↑ Hasegawa J, Iwasaki S, Matsuoka R, Ichizuka K, Sekizawa A & Okai T. (2011). Velamentous cord insertion caused by oblique implantation after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. , 37, 1698-701. PMID: 21651650 DOI.

- ↑ Yampolsky M, Salafia CM, Shlakhter O, Haas D, Eucker B & Thorp J. (2008). Modeling the variability of shapes of a human placenta. Placenta , 29, 790-7. PMID: 18674815 DOI.

- ↑ McNamara H, Hutcheon JA, Platt RW, Benjamin A & Kramer MS. (2014). Risk factors for high and low placental weight. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol , 28, 97-105. PMID: 24354883 DOI.

- ↑ Riteau AS, Tassin M, Chambon G, Le Vaillant C, de Laveaucoupet J, Quéré MP, Joubert M, Prevot S, Philippe HJ & Benachi A. (2014). Accuracy of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of placenta accreta. PLoS ONE , 9, e94866. PMID: 24733409 DOI.

- ↑ Zaideh SM, Abu-Heija AT & El-Jallad MF. (1998). Placenta praevia and accreta: analysis of a two-year experience. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. , 46, 96-8. PMID: 9701688 DOI.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Oyelese Y & Smulian JC. (2006). Placenta previa, placenta accreta, and vasa previa. Obstet Gynecol , 107, 927-41. PMID: 16582134 DOI.

- ↑ Ambrogi G, Ambrogi G & Marchi AA. (2018). Placenta Percreta and Uterine Rupture in the First Trimester of Pregnancy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol , 2018, 6842892. PMID: 29850318 DOI.

- ↑ Cheung CS & Chan BC. (2012). The sonographic appearance and obstetric management of placenta accreta. Int J Womens Health , 4, 587-94. PMID: 23239929 DOI.

- ↑ Yi KW, Oh MJ, Seo TS, So KA, Paek YC & Kim HJ. (2010). Prophylactic hypogastric artery ballooning in a patient with complete placenta previa and increta. J. Korean Med. Sci. , 25, 651-5. PMID: 20358016 DOI.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Varghese B, Singh N, George RA & Gilvaz S. (2013). Magnetic resonance imaging of placenta accreta. Indian J Radiol Imaging , 23, 379-85. PMID: 24604945 DOI.

- ↑ <pubmed>20129349</pubmed>

- ↑ Tikkanen M, Stefanovic V & Paavonen J. (2011). Placenta previa percreta left in situ - management by delayed hysterectomy: a case report. J Med Case Rep , 5, 418. PMID: 21867547 DOI.

- ↑ Dunn PM. (2006). Paul Portal (1630-1703), man-midwife of Paris. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. , 91, F385-7. PMID: 16923941 DOI.

- ↑ Harper LM, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Crane JP & Cahill AG. (2010). Effect of placenta previa on fetal growth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 203, 330.e1-5. PMID: 20599185 DOI.

- ↑ Roustaei Z, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Tuomainen TP, Lamminpää R & Heinonen S. (2018). The effect of advanced maternal age on maternal and neonatal outcomes of placenta previa: A register-based cohort study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. , 227, 1-7. PMID: 29859374 DOI.

- ↑ Yang Q, Wen SW, Oppenheimer L, Chen XK, Black D, Gao J & Walker MC. (2007). Association of caesarean delivery for first birth with placenta praevia and placental abruption in second pregnancy. BJOG , 114, 609-13. PMID: 17355267 DOI.

- ↑ <pubmed>15534438</pubmed>

- ↑ Sinkey RG, Odibo AO & Dashe JS. (2015). #37: Diagnosis and management of vasa previa. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 213, 615-9. PMID: 26292048 DOI.

- ↑ Quintero RA, Kontopoulos EV, Bornick PW & Allen MH. (2007). In utero laser treatment of type II vasa previa. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , 20, 847-51. PMID: 18050017 DOI.

- ↑ Sinha P, Kaushik S, Kuruba N & Beweley S. (2008). Vasa praevia: a missed diagnosis. J Obstet Gynaecol , 28, 600-3. PMID: 19003654 DOI.

- ↑ Gagnon R. (2009). Guidelines for the management of vasa previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Can , 31, 748-753. PMID: 19772710 DOI.

- ↑ Salihu HM, Bekan B, Aliyu MH, Rouse DJ, Kirby RS & Alexander GR. (2005). Perinatal mortality associated with abruptio placenta in singletons and multiples. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 193, 198-203. PMID: 16021079 DOI.

- ↑ Ahmed A & Gilbert-Barness E. (2003). Placenta membranacea: a developmental anomaly with diverse clinical presentation. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. , 6, 201-2. PMID: 12532260 DOI.

- ↑ Wilkins BS, Batcup G & Vinall PS. (1991). Partial placenta membranacea. Br J Obstet Gynaecol , 98, 675-9. PMID: 1883791

- ↑ Jacques SM & Qureshi F. (1993). Chronic intervillositis of the placenta. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. , 117, 1032-5. PMID: 8215826

- ↑ Pham T, Steele J, Stayboldt C, Chan L & Benirschke K. (2006). Placental mesenchymal dysplasia is associated with high rates of intrauterine growth restriction and fetal demise: A report of 11 new cases and a review of the literature. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. , 126, 67-78. PMID: 16753607 DOI.

- ↑ Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Mazaki-Tovi S, Gotsch F, Kim CJ, Kim JS, Yeo L & Hassan SS. (2009). Three-dimensional sonography of placental mesenchymal dysplasia and its differential diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med , 28, 359-68. PMID: 19244073

- ↑ Robinson WP, Lauzon JL, Innes AM, Lim K, Arsovska S & McFadden DE. (2007). Origin and outcome of pregnancies affected by androgenetic/biparental chimerism. Hum. Reprod. , 22, 1114-22. PMID: 17185351 DOI.

- ↑ Arigita M, Illa M, Nadal A, Badenas C, Soler A, Alsina N & Borrell A. (2010). Chorionic villus sampling in the prenatal diagnosis of placental mesenchymal dysplasia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol , 36, 644-5. PMID: 20503241 DOI.

- ↑ Skjaerven R, Vatten LJ, Wilcox AJ, Rønning T, Irgens LM & Lie RT. (2005). Recurrence of pre-eclampsia across generations: exploring fetal and maternal genetic components in a population based cohort. BMJ , 331, 877. PMID: 16169871 DOI.

- ↑ Leach L. (2011). Placental vascular dysfunction in diabetic pregnancies: intimations of fetal cardiovascular disease?. Microcirculation , 18, 263-9. PMID: 21418381 DOI.

- ↑ Leach L, Taylor A & Sciota F. (2009). Vascular dysfunction in the diabetic placenta: causes and consequences. J. Anat. , 215, 69-76. PMID: 19563553 DOI.

- ↑ Babic I, Tulbah M & Kurdi W. (2012). Antenatal embolization of a large placental chorioangioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep , 6, 183. PMID: 22759589 DOI.

- ↑ Moglabey YB, Kircheisen R, Seoud M, El Mogharbel N, Van den Veyver I & Slim R. (1999). Genetic mapping of a maternal locus responsible for familial hydatidiform moles. Hum. Mol. Genet. , 8, 667-71. PMID: 10072436

- ↑ Piura B, Rabinovich A, Hershkovitz R, Maor E & Mazor M. (2008). Twin pregnancy with a complete hydatidiform mole and surviving co-existent fetus. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. , 278, 377-82. PMID: 18273627 DOI.

- ↑ Rocha J, Carvalho J, Costa F, Meireles I & do Carmo O. (2012). Velamentous cord insertion in a singleton pregnancy: an obscure cause of emergency cesarean-a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol , 2012, 308206. PMID: 23243528 DOI.

- ↑ Hasegawa J, Matsuoka R, Ichizuka K, Sekizawa A, Farina A & Okai T. (2006). Velamentous cord insertion into the lower third of the uterus is associated with intrapartum fetal heart rate abnormalities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol , 27, 425-9. PMID: 16479618 DOI.

- ↑ Hill LM, Mills A, Peterson C & Boyles D. (1994). Persistent right umbilical vein: sonographic detection and subsequent neonatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol , 84, 923-5. PMID: 7970470

- ↑ Weichert J, Hartge D, Germer U, Axt-Fliedner R & Gembruch U. (2011). Persistent right umbilical vein: a prenatal condition worth mentioning?. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol , 37, 543-8. PMID: 20922781 DOI.

- ↑ Lide B, Lindsley W, Foster MJ, Hale R & Haeri S. (2016). Intrahepatic Persistent Right Umbilical Vein and Associated Outcomes: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Ultrasound Med , 35, 1-5. PMID: 26635256 DOI.

- ↑ Kim JH, Jin ZW, Murakami G, Chai OH & Rodríguez-Vázquez JF. (2018). Persistent right umbilical vein: a study using serial sections of human embryos and fetuses. Anat Cell Biol , 51, 218-222. PMID: 30310717 DOI.

- ↑ Hallak M, Pryde PG, Qureshi F, Johnson MP, Jacques SM & Evans MI. (1994). Constriction of the umbilical cord leading to fetal death. A report of three cases. J Reprod Med , 39, 561-5. PMID: 7966052

- ↑ Canda MT, Demir N & Doganay L. (2013). Velamentous and Furcate Cord Insertion with Placenta Accreta in an IVF Pregnancy with Unicornuate Uterus. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol , 2013, 539379. PMID: 24455351 DOI.

- ↑ Di Stefano M, Calabrò ML, Di Gangi IM, Cantatore S, Barbierato M, Bergamo E, Kfutwah AJ, Neri M, Chieco-Bianchi L, Greco P, Gesualdo L, Ayouba A, Menu E & Fiore JR. (2008). In vitro and in vivo human herpesvirus 8 infection of placenta. PLoS ONE , 3, e4073. PMID: 19115001 DOI.

- ↑ Sinzger C, Müntefering H, Löning T, Stöss H, Plachter B & Jahn G. (1993). Cell types infected in human cytomegalovirus placentitis identified by immunohistochemical double staining. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol , 423, 249-56. PMID: 8236822

- ↑ Tao L, Suhua C, Juanjuan C, Zongzhi Y, Juan X & Dandan Z. (2011). In vitro study on human cytomegalovirus affecting early pregnancy villous EVT's invasion function. Virol. J. , 8, 114. PMID: 21392403 DOI.

- ↑ Berger BA, Bartlett AH, Saravia NG & Galindo Sevilla N. (2017). Pathophysiology of Leishmania Infection during Pregnancy. Trends Parasitol. , 33, 935-946. PMID: 28988681 DOI.

- ↑ Figueiró-Filho EA, Duarte G, El-Beitune P, Quintana SM & Maia TL. (2004). Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) and pregnancy. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol , 12, 31-40. PMID: 15460194 DOI.

- ↑ Gantert M, Been JV, Gavilanes AW, Garnier Y, Zimmermann LJ & Kramer BW. (2010). Chorioamnionitis: a multiorgan disease of the fetus?. J Perinatol , 30 Suppl, S21-30. PMID: 20877404 DOI.

- ↑ Kim CJ, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Yoo W, Dong Z, Topping V, Gotsch F, Yoon BH, Chi JG & Kim JS. (2010). The frequency, clinical significance, and pathological features of chronic chorioamnionitis: a lesion associated with spontaneous preterm birth. Mod. Pathol. , 23, 1000-11. PMID: 20348884 DOI.

- ↑ Roberts DJ. (2008). Placental pathology, a survival guide. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. , 132, 641-51. PMID: 18384216 [641:PPASG2.0.CO;2 DOI].

Reviews

Costa ML, de Moraes Nobrega G & Antolini-Tavares A. (2020). Key Infections in the Placenta. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. , 47, 133-146. PMID: 32008664 DOI.

Yang C, Song G & Lim W. (2019). A mechanism for the effect of endocrine disrupting chemicals on placentation. Chemosphere , 231, 326-336. PMID: 31132539 DOI.

Bartels HC, Postle JD, Downey P & Brennan DJ. (2018). Placenta Accreta Spectrum: A Review of Pathology, Molecular Biology, and Biomarkers. Dis. Markers , 2018, 1507674. PMID: 30057649 DOI.

Garmi G & Salim R. (2012). Epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and management of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol Int , 2012, 873929. PMID: 22645616 DOI.

Elsayes KM, Trout AT, Friedkin AM, Liu PS, Bude RO, Platt JF & Menias CO. (2009). Imaging of the placenta: a multimodality pictorial review. Radiographics , 29, 1371-91. PMID: 19755601 DOI.

Abramowicz JS & Sheiner E. (2007). In utero imaging of the placenta: importance for diseases of pregnancy. Placenta , 28 Suppl A, S14-22. PMID: 17383721 DOI.

Articles

Messerschmidt A, Baschat A, Linduska N, Kasprian G, Brugger PC, Bauer A, Weber M & Prayer D. (2011). Magnetic resonance imaging of the placenta identifies placental vascular abnormalities independently of Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol , 37, 717-22. PMID: 21105016 DOI.

Hargitai B, Marton T & Cox PM. (2004). Best practice no 178. Examination of the human placenta. J. Clin. Pathol. , 57, 785-92. PMID: 15280396 DOI.

Yetter JF. (1998). Examination of the placenta. Am Fam Physician , 57, 1045-54. PMID: 9518951

Search PubMed

Search Pubmed: Placenta Abnormalities | Placenta Accreta | Placenta Increta | Placenta Percreta | Placenta Previa | Vasa Previa

Historic

Duncan JM. (1873). On the Mechanism of Arrestment of Hæmorrhage in Cases of Placenta Prævia. Edinb Med J , 19, 520-532. PMID: 29640980

Duncan JM. (1873). On the Hæmorrhage That Occurs during the Continuance of Pregnancy in Cases of Placenta Prævia. Edinb Med J , 19, 385-398. PMID: 29640908

Simpson AR. (1879). Observations on Some Forms of Sterility and on Placenta Prævia in First Labours: With Illustrative Cases. Edinb Med J , 24, 769-782. PMID: 29640651

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- American Fam Physician. (1998) Examination of the Placenta PMID 9518951

| Placenta Terms (expand to view) |

|---|

with an incidence of about 2.8 per 1,000 pregnancies, there is also a rarer form of extra-abdominal varices.PMID 24883288

with an incidence of about 2.8 per 1,000 pregnancies, there is also a rarer form of extra-abdominal varices. PMID 24883288

|

| Other Terms Lists |

|---|

| Terms Lists: ART | Birth | Bone | Cardiovascular | Cell Division | Endocrine | Gastrointestinal | Genital | Genetic | Head | Hearing | Heart | Immune | Integumentary | Neonatal | Neural | Oocyte | Palate | Placenta | Radiation | Renal | Respiratory | Spermatozoa | Statistics | Tooth | Ultrasound | Vision | Historic | Drugs | Glossary |

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2026, March 9) Embryology Placenta - Abnormalities. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Placenta_-_Abnormalities

- © Dr Mark Hill 2026, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G