Paper - The formation of the venous valves, the foramen secundum and the septum secundum in the human heart

| Embryology - 28 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Odgers PNB. The formation of the venous valves, the foramen secundum and the septum secundum in the human heart. (1935) J. Anat., 69: 412-422. PMID 17104548

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

The Formation of the Venous Valves, the Foramen Secundum and the Septum Secundum in the Human Heart

By P. N. B. Odgers

From the Department of Human Anatomy, University of Oxford

So many of the details in the development of the heart have been worked out in the chick or in such Mammals as the rabbit or the pig, that it seemed worth while to attempt the re-investigation of some of them in human embryos. For this purpose I made use of the following material in this department: human embryos of 5, 6-5, 7-1, 11-2, 1+, 17-5, 23, 28-5, 46 an(l 61 mm. in crown-rump length. Reconstruction models of the venous end of the heart were made from the 5, 7-1, 11-2, 17-5, 28-5 and 46 mm. specimens. I also had the opportunity kindly afforded me by Prof. J. Ernest Frazer of studying from his extensive series the hearts in a 4--5- and a 4-9-mm. embryo, in two 5-mm. and two 8-1nn1. embryos and in a 9-mm. embryo.

I. The Formation of the Venous Valves

Waterston (1918) described both the venous valves as formed by the invagination of the right horn of the sinus venosus into the right auricle. While this is certainly so in the case of the right valve, the left one has, I consider, an entirely different origin. The right valve is originally the eoapted walls of sinus and auricle and increases in size with the increasing intussusception of the former into the latter chamber. A well-defined groove on the outer surface of the models of the 5- and 7-1-mm. stages marks the sinu-auricular junction and the site of the right valve, and this is seen in Plate I, fig. 5.

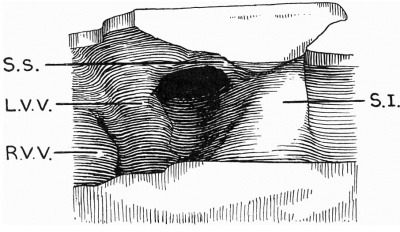

The left valve, on the other hand, is derived as a delamination of the septum primum. It appears in my 5 mm. model (text-fig. 1) — I could find no trace of its formation in Frazer's 4.5 or 4.9-mm embryos — as a ridge, most pronounced above, anterior to the sinu-auricular orifice and the right venous valve. At this stage it is the more prominent of the two valves. Above, its anterior border is connected with the septum primum by an elevation arching forwards, which bounds the commencing intersepto-valvular space and is the beginning of the septum spurium or tensor Valvulae. Below it merges into the expanded base of the septum. There is no external sulcus corresponding to the site of the left valve like that described above for the right one. As I interpret them its formation is well shown in the microphotographs reproduced in Plate I. The septum primum is formed in a line of stasis, due apparently to the attachmcnt of the mesocardium dorsally and the formation ventrally of the upper (or dorsal) aurieldo-ventricular endocardial cushion. On either side of this stasis line the auricles are free to expand. Into the subendocardial space here the myocardium proliferates, commencing first, as is seen in Frazer’s 4-9-mm. specimen, at the attachment of the mesocardium and spreading up on to the roof from here (Plate I, fig. 1). The succeeding three figures in Plate I, which are photographs of alternate sections next below fig. 1, show that a lacuna appears so that the myocardial proliferation is divided into right and left portions, which gradually separate entirely from each other. The left limb forms the septum primum, the right limb the left valve, while the connection between the two is the anlage of the septum spurium. This latter, as my model shows well, is at this stage continuous with the left valve alone and has no connection with the right one. These observations were confirmed in one of Frazer’s 5 mm. hearts, which presented precisely the same appearances. In another 5 mm specimen of his the condition of the valve was more advanced and resembled that seen in my 6-5~mm. embryo. In the 6.5 and 7.1-mm. stages the increasing

Text-fig. 1. Drawing of a model of the auricles in a 5 mm embryo. The centre portion of the posterior wall is represented, viewed from the front. SJ. septum primum; S.s. septum spurium; R.V.V. right venous valve; L.V. V. left venous valve.

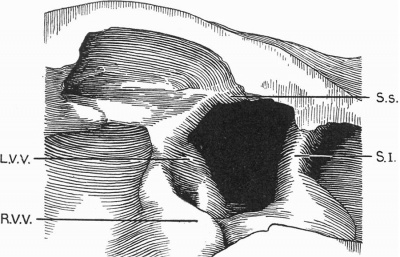

invagination of the right sinus horn, which has made the right valve, projecting now well in front of the left, the more prominent of the two, has also reached and taken up the left venous valve so that the latter now forms the left lip of the sinu-auricular opening (text-fig. 2). The extraordinary increase in the height and depth of the intersepto-valvular space must also be a subsidiary factor in producing this change. The upper ends of both valves have now joined each other in a common superior fornix. T 0 this the left valve has brought with it the septum spurium, which still runs anteriorly i11to the septum primum and thus still betrays the septal origin of the valve. Below, the left valve still ends in the expanded base of the same septum.

Chang (1931) has given an account of the formation of the left venous valve in the chiek’s heart, which in some ways seems to be comparable to mine. He described it as being formed in two stages. First at 62 hours of incubation the endocardial proliferation along the ventral end of the dorsal mesocardium, which is going to form the septum primum, makes the temporary left boundary of the sinu-atrial opening. The permanent left valve arises later at 96 hours of incubation from the dorsal atrial wall and is continuous caudally with the earlier formation.

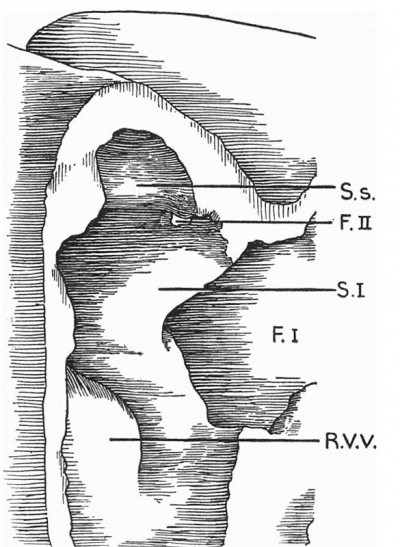

II. The Formation of the Foramen Secundum

The first appearance of this was found in my 7.1 mm specimen. There was no sign of it in any of the earlier embryos I examined. Here, close to the junction of the anterior end of the septum with the roof, a small hole is seen which extends over two sections only (text-fig. 3). It seems to be formed in this way. In my description of the formation of the left venous valve I have shown that the myocardium proliferates into the septum primum from the dorsal wall of the auricle. At the 6-5-mm. stage, as is seen in the microphotograph of the septum (Plate II, fig. 1), the dorsal outgrowth is met by a smaller pyramidal proliferation from the ventral wall. The section which is figured is four sections above the foramen primum and, as this is approached, the ventral outgrowth becomes less and less obvious until it finally fails to meet the dorsal one and the foramen occurs. Three sections above the level of that photographed the two projections, dorsal and ventral, have so perfectly blended that the septum appears to be composed of a continuous myocardial layer. The appearance presented by similar sections in my 7-1-mm. embryo is very much the same.

Text-fig. 2. Drawing of a. model of the auricles in a 7.1 mm embryo. The centre portion of the posterior wall is represented, viewed from the front. SJ. septum primum; S.s. septum spurium; R. V. V. right venous valve; L. V. V. left venous valve.

Text-fig. 3. Drawing of a. model of the auricles in a 7.1 mm embryo, viewed from the right side, to show the commencement of the foramen secundum. S.I. septum primum; S.s. septum spurium; F.I. foramen primum; F.II. foramen secundum; R.V.V. right venous valve.

In the series of microphotographs (Plate II, figs. 2-10) the dorsal and ventral myocardial outgrowths are seen at first four sections above the foramen secundum. At this level (Plate II, figs. 2-3) they meet but are not in accurate contact, the ventral proliferation being slightly to the left of the dorsal one. The contact between the two becomes less and less until a foramen, the foramen secundum, occurs. Below this the two outgrowths meet again in the same line for three sections, when the ventral outgrowth decreases and the foramen primum appears. The cause of either foramen, primum or secundum, seems to be the same, namely the failure of the dorsal and ventral proliferations to make contact. The only difference between the two levels is that, while in the case of the foramen secundum the dorsal proliferation seems to be at fault, in the case of the foramen primum, as was previously noticed in the earlier 6-5-mm. specimen, the ventral outgrowth is the one that fails. I would suggest then that the foramen secundum is due to a local failure of growth to complete the septum rather than that it is caused by the localised destruction of a septum previously perfect or, expressed differently, the foramen secundum is a portion of the foramen primum which has not been obliterated. I can see no ragged edges to the foramen as Waterston described in his 6-mm. heart. Both projections are clearly defined with intact endocardium.

As will be realised, these observations of mine are entirely heterodox. While Born (1888) wrote of the foramen secundum as “appearing”, Tandler (1912) and all other observers since have described it as a gradual thinning and final break through of the septum primum. The only paper I have come across in which any doubt is expressed about this question is one by Retzer (1908), who in his description of the formation of the foramen secundum in the pig’s heart wrote: “ I am at present unable to say whether the perforation one sees is due to a rupture of the thin lamella, which at first consists of but two rows of cells, or is actually an opening formed during the growth of the heart.” I am not sure that I cannot find some indirect support in the observations of Rose (1890) on the comparative embryology of the heart. In Birds, Monotremes and Marsupials he described the secondary break through of the septum primum as being closed quite quickly by the growth of the endocardium. In the heart of the calf, sheep and horse there are multiple openings in the septum, which together represent the foramen secundum, the smaller ones of these being obliterated subsequently, according to his account, by endocardial proliferation. This description suggests at all events that there is some active proliferation going on, and I would suggest that multiple openings could a prion’ be expected to result rather from a local failure of growth than from multiple perforations of a once perfect septum. I cannot find anywhere any figures showing the commencement of the foramen secundum. In an 8-mm. embryo of Frazer’s which I examined it is already a large hole in the septum, and all the text-book illustrations figure it at this or at a somewhat later stage. I think this may be the reason for both Born and Tandler describing its commencement as occurring more posteriorly than it does. Born (1889) in the rabbit described it as appearing where the posterior auricular wall curves into the roof, while Tandler in Keibel and Mall wrote that it is formed “ either directly at the line of origin of the septum on the posterior upper wall of the atrium or immediately below it”.

It is interesting to speculate as to the reason why the foramen primum should normally close, while the foramen secundum should appear and so quickly become a large opening. Possibly the direction of the blood stream may be the causal factor. At 5 mm. the widest part of the sinu-auricular opening is in the floor of the right auricle; the rest of it is a mere chink. At this stage the blood stream is directed chiefly to the roof and may be responsible for the delamination of the septum, the appearance of the left venous valve and of the intersepto-valvular space. At 7-1 mm. the right Venous valve has advanced so far into the right auricle and has come up so much on its floor that its tip reaches to the same level as the anterior border of the septum primum. The sinu-auricular opening is now wider on the posterior wall than on the floor, and the blood stream is directed by the right valve to the left against the septum rather than against the roof. The foramen primum is thus in front of the main blood flow and can close perhaps, as Waterston suggests, chiefly by the increase in size of the endocardial auriculo-ventricular cushions, and their extension dorsally, while the foramen secundum bears increasingly the brunt of the blood stream and is increasingly irrupted.

III. The Formation of the Septum Secundum

At the 7.1 mm stage the groove in the roof which marks the separation of the two auricles corresponds accurately to the line of the septum primum. In the 11-2-mm. model this inter-auricular cleft is obviously to the right of the septum primum and is in the same plane as the septum spurium and the left venous valve, the septum primum being laid back almost against the dorsal wall of the left auricle with the pulmonary vein opening into the narrow cleft between the two. Frazer (1931) suggests that this change is due to the left auricle increasing the area of its roof towards the right. I would rather put it down to the counter-clockwise rotation of the auricles, which seems to be due primarily to the increasing projection of the right horn of the sinus venosus and its valves into the right auricle, the tip of the right venous valve actually projecting into the right auriculo-ventricular orifice at this period. The stage is thus set, so to say, for the formation of another septum. At 17.5 mm the first definite indication of the septum secundum is seen as a projection into the intersepto-valvular space from the dorsal wall of the right auricle close to the roof to the left of the septum spurium (Plate III, fig. 1). Corresponding to this projection there is a very definite inflection of the auricular wall at its junction with the right sinus horn. Traced caudalwards, the incipient septum soon blends with the left side of the left venous valve. Further in this same heart another projection is to be seen from the ventral wall. This arises from the dorsal border of the septum intermedium—a convenient term I think to retain for the fused auriculo-ventricular cushions—just to the right of the septum primum in the lower part of the intersepto-valvular space (Plate III, fig. 2). It can be traced through ten sections and blends, as it flattens out, with the extremity of the left venous valve. Something comparable to this is to be observed in my 11.2 mm embryo. In this latter there is a knoblike projection from the right side of the lower part of the septum primum close to its union with the septum intermedium. This is figured in Plate III, fig. 3, and can be seen in seven sections above and in three sections below that photographed before it flattens out in the auriculo-ventricular cushions.

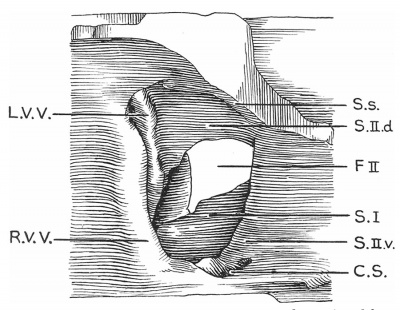

In my 28.5 mm embryo the septum secundum is much further developed and forms at this stage with the left venous valve a complete circular diaphragm (text-fig. 4). As I interpret it, the septum secundum appears to consist of two parts. The dorsal segment springs from the posterior wall at its junction with the roof in exactly the same plane as the interauricular cleft. It arches over the roof of the auricle to the left of the left venous valve, which is quite a distinct projection on its right side. Just where the ventral wall of the auricle joins the roof this dorsal portion meets the upper end of a ridge projecting from the ventral wall. As this ventral moiety of the septum is traced caudalwards it becomes more prominent and ends in a bifurcation, becoming continuous by its larger right limb with the sinus septum and by its smaller left limb with the left venous valve. The latter forms with the lower end of the septum primum a little bay, which projects into the opening of the inferior vena cava and represents the caudal extremity of the intersepto-valvular space (text-fig. 5). My reasons for suggesting that the septum‘ secundum is composed of two separate outgrowths here are:

(1) While the dorsal segment is most marked above, the ventral segment increases in thickness as it is traced caudally. Where these two meet at the anterior superior angle, the septal projection is minimal.

(2) The two ridges are not accurately in the same plane, the ventral outgrowth being slightly to the right of the dorsal one. Their relations therefore to the left venous valve are different. This valve is on the right of the dorsal moiety, while its termination runs into the left limb of the bifurcating ventral projection. While the septum spurium (tensor valvulae) ends anteriorly just above the upper extremity of the ventral half of the septum secundum, it appears in my model as a distinct ridge arching over the auricular roof to the right of this septum, which seems to be entirely independent of it in its formation. Favaro (1913) found that in the guinea-pig and sheep the septum spurium joins the newly formed septum secundum. While Morrill (1916) noted that this does not occur in the pig’s heart, he suggested that in the human embryos he examined its course and relations seemed to be more like those described by Favaro in the guinea-pig and sheep.

Text-fig. 4. Drawing of a. model of the auricles in a 28.5 mm embryo, viewed from the right side, to show the venous valves and the septal formations. SJ. septum primum; S.s. septum spurium; F.II. foramen secundum; R.V.V. right venous valve; L.V.V. left venous valve; C.S. coronary sinus; S.II.d. septum secundum, dorsal segment; S.Il .12. septum secundum, ventral segment.

Text-fig. 5. Drawing of the lower portion of the same model as text-fig. 4, of a 28-5-mm. embryo, to show the termination of the left venous valve. This section is immediately below that represented in text-fig. 4 and is viewed from above. S.I. septum primum; :S’i.s. Sinus septum; C'.S. coronary sinus; R. V. V. right venous valve; L. V. V. left venous valve; I. V.C'. inferior vena cava.

In my 46 mm specimen (text-fig. 6) the development of the septum secundum appears to be less advanced in most respects than in the previous 28-5-mm. embryo. The two projections, dorsal and ventral, which are going to form it have not met and therefore appear the more distinct each from the other. On the other hand, there is no obvious left venous valve except above and below. Above, the notching of the anterior border of the dorsal projection indicates its compound origin, while below, the termination of the valve now appears as a ridge running almost at right angles to the lower end of the septum secundum towards the caudal and dorsal border of the septum primum. This ridge projects into the dorsal wall of the inferior vena cava just where it is opening into the auricle and must be the remains of the dorsal half of the bay made by the left venous valve in the 28-5 mm. stage (text-fig. 5). The ventral projection is very prominent below, and while, as in the previous specimen, it is continuous on its right side with the sinus septum, the main portion of it runs as a tapering ridge to join the septum primum. This ridge projecting opposite that on the dorsal wall of the inferior vena cava described above must represent the ventral half of the bay made by the left venous valve in the 28-5-mm. embryo; the rest of the bay has gone and the lower end of the interseptovalvular space has thus been obliterated.

Text-fig. 6. Drawing of a model of the septa] structures in a 46-mm. embryo, viewed from the right side. The right venous valve has been removed. SJ. septum primum; R. V. V. cut end of right venous valve; L. V. V. left venous valve; S.V.C'. superior vena cava; 8.11 .d. septum secundum, dorsal segment; SJ I .12. septum secundum, ventral segment.

In spite of such views as those expressed by Retzer (1908), who regarded the septum secundum as a passive formation—“ in the pig the septum secundum in Born’s sense does not exist: search for it was made in vain in the embryonic hearts of man, monkey and rabbi ”—or by Waterston (1918), who suggested that the edge of the limbus fossae ovalis was formed by the fused left venous valve and the remains of the septum primum, while the whole of the dorsal and oral portion of the so-called septum secundum was merely the result of the coaptation of the adjacent walls of the two atria, I think it is generally agreed that the septum secundum is due to a local myocardial proliferation. Born (1889), working chiefly at the development of the ra.bbit’s heart, described it as arising from the roof and the upper part of the posterior Wall of the auricle as a crescentic ridge, which grew over the roof and on to its anterior wall, and his account has usually been followed in the description of this septum in the human heart. There is, however, considerable authority for a ventral origin of this septum in Man and other Mammals. Rose (1890) originally described it as beginning “on the anterior and upper atrial wall, as a ridgelike infolding, the septum musculare, which together with the septum intermedium is formed into a closed ring diaphragm, the annulus ovalis” (Morrill’s translation). Morrill (1916), in the pig’s heart, found the septum commencing as a spur from the septum intermedium at the anterior inferior corner of the auricle and spreading upwards and backwards along the roof to the posterior wall, where it flattens down and may become continuous with_ two or three muscular trabeculae in the intersepto-valvular space. He denies, therefore, that in this animal any dorsal outgrowth contributes to the formation of the septum secundum. Favaro’s description (1913), based on guinea-pig and sheep embryos, was very similar to the latter. In human embryos of 12 and 14 mm. Morrill noted that “in the lower part of the right auricle of both these embryos there was a thick connective tissue ridge or prominence continuous with the fused endocardial cushions, and partly overlaid and invaded by developing muscle. As in the pig this musculature was continuous with that of the septum primum and the sinus valves. The resemblance between this structure and that described for the pig in the corresponding place is so close that I am inclined to think it represents the origin of the septum secundum in Man.” Again, Thyng (1914), in describing a 17-8-mm. human embryo, found that “just where the left sinus valve meets the right side of the septum primum there is a ridge or tubercle which probably represents the caudal end of the future septum secundum”. This last observation is apparently exactly similar to what I found myself in my 17-5-mm. specimen (Plate III, fig. 2). Here the projection is into the intersepto-valvular space from the septum intermedium. The only difficulty, if indeed this is a real one, in supposing that_ this is the commencement of the ventral outgrowth so conspicuous in the 28-5-mm. embryo, is that at the 17-5-mm. stage the projection is to the left of the left venous valve, and one must predicate that, as this outgrowth increases in size, it takes up the anterior attachment of the left valve to bulge more prominently to the right of it.

As the result of my own observations I would maintain that in the human heart there are two discrete outgrowths, a dorsal one and a ventral one, which, meeting at the anterior-superior angle of the auricle, together form the septum secundum.

Lastly, I suggest the probability that this septum is formed ultimately, at all events, from sinus musculature. I cannot prove this, because, while in the earlier stages the sinus myocardium is readily distinguishable from that of the auricle—it is more cellular and stains more deeply—this is not so obvious in the more advanced embryos. The dorsal outgrowth corresponds, as I have said, to an inflection of the sinu-auricular junction, while the incorporation of the left venous valve with it must bring sinus tissue to it. Again, the ventral portion is continuous with the sinus septum and the termination of the left venous valve. Retzer described the invasion of the septum intermedium by the musculature of the sinus venosus, while Morrill concludes that in the pig a part of this musculature at least thickens to form the root of the septum secundum.

Conclusions

- While the right venous valve is formed by the coaptation of the wall of the right horn of the sinus venosus with that of the auricle and grows by the increasing invagination of the former into the latter cavity, the left valve has its origin in a delamination of the septum primum.

- The appearance of the foramen secundum is due to a local failure of growth of the septum primum rather than to a. breakdown of the septum already formed. '

- he septum secundum has a double origin. Not only is there a dorsal outgrowth in association with the upper end of the left venous valve, but there is also a ventral proliferation from the septum intermedium commencing to the right of the anterior inferior angle of the septum primum and blending later with the sinus septum and the lower end of the left venous valve.

I gladly acknowledge the help I have received from Mr W. Chesterman, of this Department, in the making of my models and in the preparation of the microphotographs.

References

Bonn, G. (1888). Anat. Anz. Bd. 111, S. 606.

- (1889). Arch. Mikr. Anat. Bd. XXXIII, S. 284.

CHANG, CHUN (1931). Anat. Rec. vol. L, p. 9.

FAVARO, G. (1913). Ricerche embriolog. ed. anatom. intorno at more dei vertebrati, Parte I. Padova.

Frazer JE. A Manual of Embryology. (1940) Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, London. p. 311.

MORRILL, C. V. (1916). Amer. J. Anal. vol. xx, p. 351.

RETZER, R. (1908). Anat. Rec. vol. II, p. 149.

Rose, C. (1890). Morph. Jb. Bd. XVI, S. 27.

Tandler J. The Development of the Heart. (1912) Sect. II, chapt. 18, vol. 2, in Keibel F. and Mall FP. Manual of Human Embryology II. (1912) J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia., pp. 534-570., p. 73.

WATERSTON, D. (1918). Trans. roy. Soc. Edinb. vol. LII, pt. 11, p. 257.

Explanation of Plates I—III

Plate I

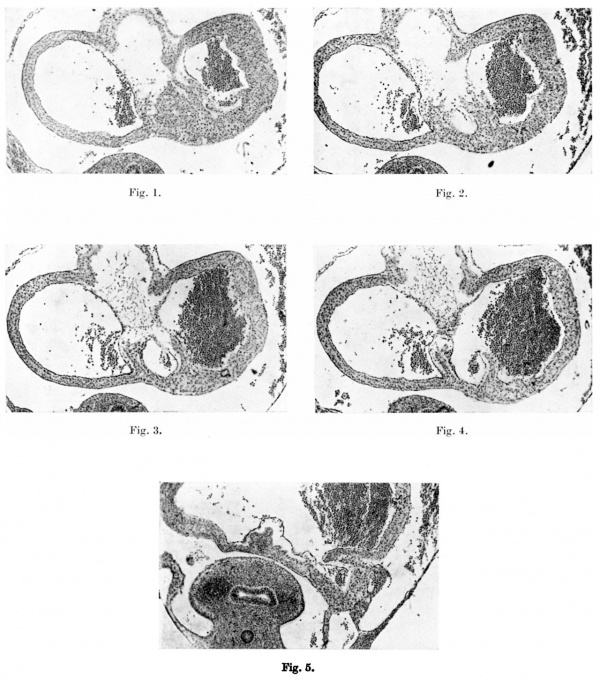

Figs. 1-4. These microphotographs of sections of the aurieles in a 5-mm. embryo ( x 60) show in fig. I the myocardium spreading into the subendocardial space from the dorsal wall to form the septum primum. Figs. 2-4 are photographs of alternate sections next below this and in them a lacuna appears in the myocardial proliferation, ultimately splitting this into two. The left limb forms the septum primum, the right limb the left venous valve, the connection between the two persisting as the septum spurium.

Fig. 5 is a microphotograph of the same heart 11 sections below the last. This shows the right valve as being formed by the coaptation of the anterior wall of the right horn of the sinus venosus with the posterior wall of the auricle. The left venous valve is seen as a small projection immediately to the left and slightly anterior to the right valve.

Plate II

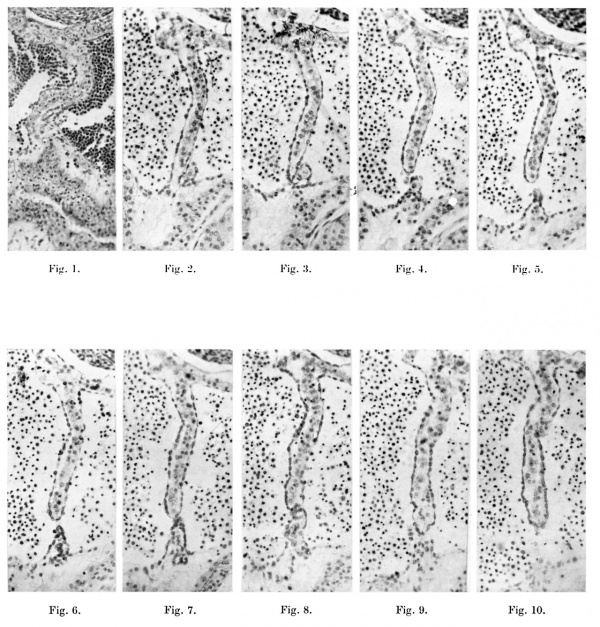

1. A microphotograph of the septum primum in a 6-5-mm. embryo ( x 124). This is four sections above the foramen primum and shows that the larger dorsal myocardial proliferation is meeting a much smaller cone-shaped ventral one.

Figs. 2-10. These are all microphotographs of the septum primum in a 7 -1-mm. embryo ( x 124).

The dorsal wall of the auricle is towards the top of the page. Fig. 2 shows that the dorsal myocardial proliferation has not quite reached the ventral end of the septum but is in contact with a small ventral outgrowth to the left of it. In the next section (fig. 3) the septum just fails to meet the ventral wall and in two sections below this last (fig. 4) contact is only maintained by some proliferating endocardium. The succeeding two sections (figs. 5 and 6) show no contact at all between the two outgrowths; thisisthe foramen secundum. In figs. 7 and 8 which represent the next section and the next but one below the last, contact is again made by the two out growths, but in the next alternate sections (figs.'9 and 10) the ventral proliferation is seen to gradually fail and the foramen primum thus begins.

Plate III

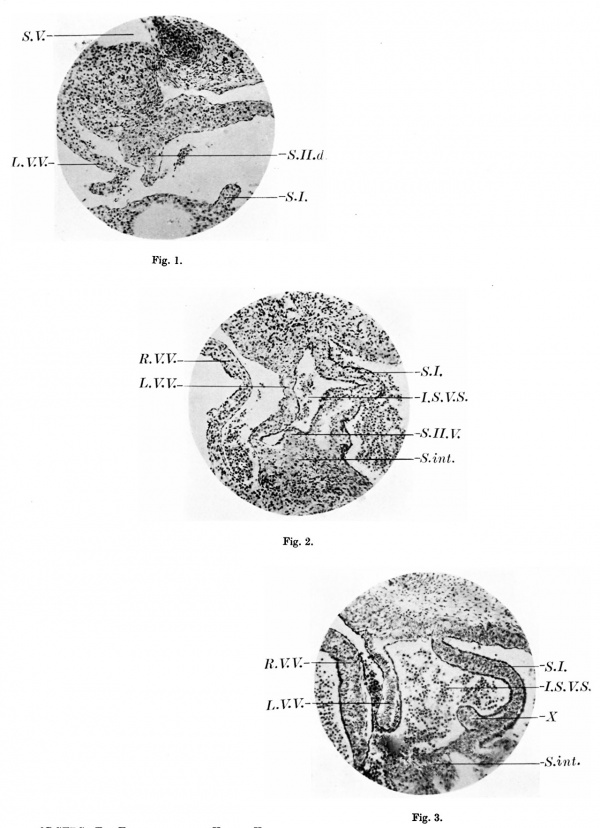

1. A section of the heart of a 17.5 mm embryo ( x 103) showing the dorsal outgrowth which forms the septum secundum. S.II.d. septum secundum; SJ. septum primum; L. V.V. left venous valve; S. V. sinus venosus.

2. A section of the heart of a 17.5 mm embryo ( x 103) 34 sections below fig. 1, to show the commencement of a ventral outgrowth which will also form the septum secundum. SJ I . V. septum secundum; S.I. septum primum; R. V. V. right venous valve; L. V. V. left venous valve; S.int. septum intermedium; I .S. V.S. intersepto-valvular space.

3. A section of the heart of an 11.2 mm embryo ( x 103) to show the knoblike projection from the right side of the septum primum, X. 8.1. septum primum; R. V. V. right venous valve; L. V.V. left venous valve; Sint. septum intermedium; I .S. V.S. intersepto-valvular space.

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 28) Embryology Paper - The formation of the venous valves, the foramen secundum and the septum secundum in the human heart. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Paper_-_The_formation_of_the_venous_valves,_the_foramen_secundum_and_the_septum_secundum_in_the_human_heart

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G