Cardiovascular System - Ductus Venosus

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Introduction

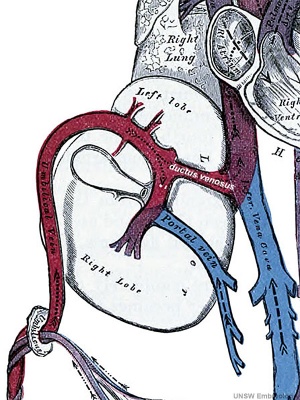

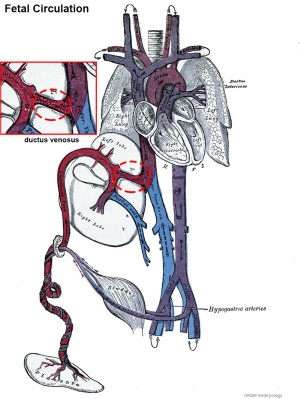

The ductus venosus describes the vitelline blood vessel lying within the liver that connects (shunts) the portal and placental (umbilical) veins to the inferior vena cava and also acts to protect the fetus from placental over-circulation. Blood flow within the ductus venosus is sensitive to changes in placental venous pressure, blood viscosity, and the regulation of ductus venosus diameter.

During the second and third trimester, the mean fraction of placental blood shunted through the ductus venosus reduces from 30% to 20%, suggesting a fetal liver priority of circulation.. [1]

Postnatally this shunt functionally closes (93% of infants at 2 weeks) then structurally closes and degenerates to form it the ligamentum venosum. A comparison at day 3 of postnatal shunt closures; 94% of infants have a closed ductus arteriosus, while only 12% had a closed ductus venosus.[2]

Abnormalities include an absence or patently. Absence can cause hydrops fetalis and the umbilical vein then drains directly into the inferior vena cava or right atrium. A patent or persistent ductus venosus describes the postnatal failure of this vessel to close.

See also the related pages foramen ovale, ductus arteriosus, Arterial Development, Venous Development, Placental Villi Blood Vessels and coronary circulation.

- Historic - Ductus Venosus: 1923 Ductus Venosus

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Ductus Venosus | Patent Ductus Venosus | hydrops fetalis |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

Embryonic Development

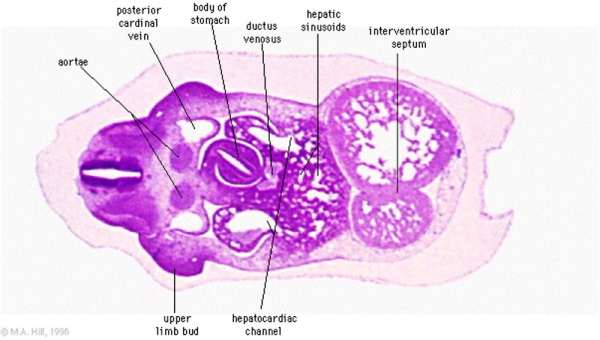

Stage 13

|

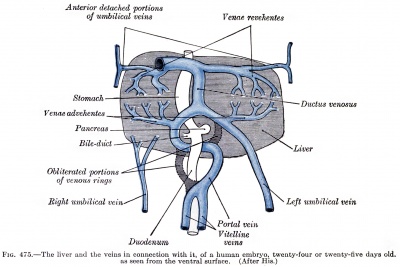

Human Embryo Liver and Associated Veins

Human embryo liver ventral surface view. Figure after {{His)).

|

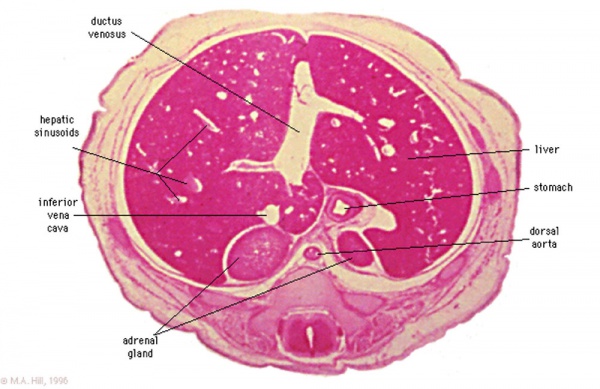

Stage 22

Fetal Development

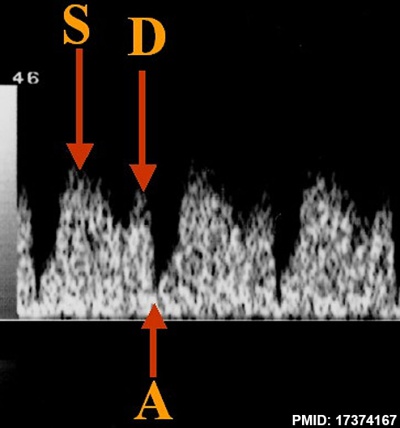

Fetal ductus venosus ultrasound[8]

- Links: ultrasound

Physiology

Fetal ductus venosus pressure wave

Abnormalities

Patent Ductus Venosus

Failure of the ductus venosus to close may result in a range of down-stream effects including: galactosemia, hypoxemia, encephalopathy with hyperammonia, and hepatic dysfunction.[4]

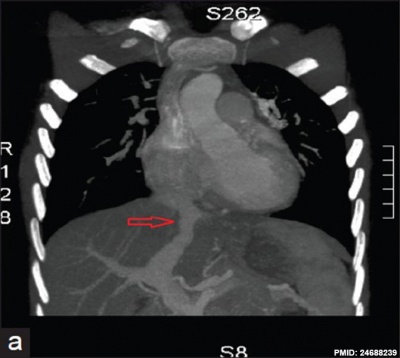

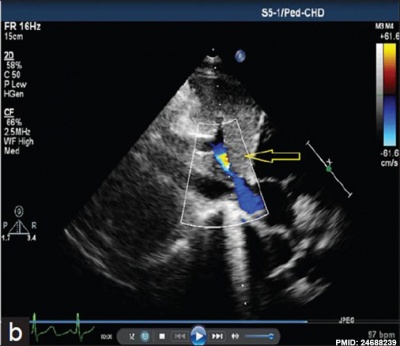

Patent or Persistent ductus venosus (postnatal 8 years) connecting the left portal vein to the inferior vena cava.[9]

|

| |||

| Tomography | Two-dimensional echocardiography | |||

|

References

- ↑ Kiserud T. (2001). The ductus venosus. Semin. Perinatol. , 25, 11-20. PMID: 11254155

- ↑ Fugelseth D, Lindemann R, Liestøl K, Kiserud T & Langslet A. (1997). Ultrasonographic study of ductus venosus in healthy neonates. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. , 77, F131-4. PMID: 9377136

- ↑ Sidhu PS & Lui F. (2019). Embryology, Ductus Venosus. , , . PMID: 31613539

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Poeppelman RS & Tobias JD. (2018). Patent Ductus Venosus and Congenital Heart Disease: A Case Report and Review. Cardiol Res , 9, 330-333. PMID: 30344833 DOI.

- ↑ Gürses C, Karadağ B & İsenlik BST. (2018). Normal variants of ductus venosus spectral Doppler flow patterns in normal pregnancies. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , , 1-7. PMID: 30153762 DOI.

- ↑ Lund A, Ebbing C, Rasmussen S, Kiserud TW & Kessler J. (2018). Maternal diabetes alters the development of ductus venosus shunting in the fetus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand , , . PMID: 29752712 DOI.

- ↑ Turan OM, Turan S, Sanapo L, Willruth A, Wilruth A, Berg C, Gembruch U, Harman CR & Baschat AA. (2014). Reference ranges for ductus venosus velocity ratios in pregnancies with normal outcomes. J Ultrasound Med , 33, 329-36. PMID: 24449737 DOI.

- ↑ da Silva FC, de Sá RA, de Carvalho PR & Lopes LM. (2007). Doppler and birth weight Z score: predictors for adverse neonatal outcome in severe fetal compromise. Cardiovasc Ultrasound , 5, 15. PMID: 17374167 DOI.

- ↑ Subramanian V, Kavassery MK, Sivasubramonian S & Sasidharan B. (2013). Percutaneous device closure of persistent ductus venosus presenting with hemoptysis. Ann Pediatr Cardiol , 6, 173-5. PMID: 24688239 DOI.

Reviews

Sidhu PS & Lui F. (2019). Embryology, Ductus Venosus. , , . PMID: 31613539

Kiserud T. (2001). The ductus venosus. Semin. Perinatol. , 25, 11-20. PMID: 11254155

Articles

Fugelseth D, Lindemann R, Liestøl K, Kiserud T & Langslet A. (1997). Ultrasonographic study of ductus venosus in healthy neonates. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. , 77, F131-4. PMID: 9377136

Search Pubmed

Search Pubmed: Ductus Venosus

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Cardiovascular System - Ductus Venosus. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Cardiovascular_System_-_Ductus_Venosus

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G