Abnormal Development - Zika Virus

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| Educational Use Only - Embryology is an educational resource for learning concepts in embryological development, no clinical information is provided and content should not be used for any other purpose. |

Introduction

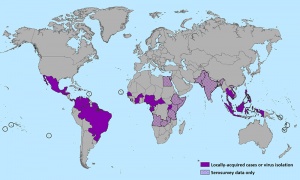

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-borne flavivirus related to dengue virus first isolated from a rhesus monkey in Zika forest, Uganda (1947). Transmitted by mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) it was then identified in humans in Nigeria in 1954 and subsequently in South America, Asia and Pacific regions. More recently in Australia from returning travellers.[2]

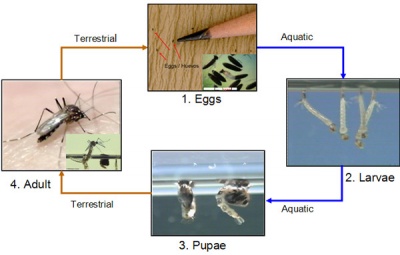

Mosquito bites lead to an initial infection of skin cells.[3] The virus may also be transmitted transplacentally or during delivery.[4]

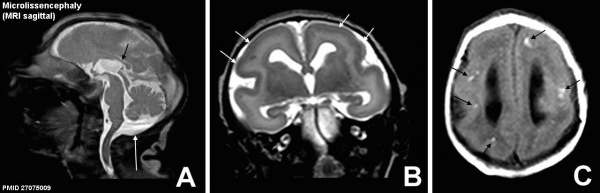

Now good evidence, from Brazil and other South American countries, for association with neural abnormalities (microcephaly, vision development, Guillian Barre Syndrome). This possible association in other developmental systems requires more clinical and scientific evidence before being confirmed.

Microlissencephaly

Some Recent Findings

Zika virus infection in pregnant rhesus macaques causes placental dysfunction and immunopathology[8] "Zika virus (ZIKV) infection during pregnancy leads to an increased risk of fetal growth restriction and fetal central nervous system malformations, which are outcomes broadly referred to as the Congenital Zika Syndrome (CZS). Here we infect pregnant rhesus macaques and investigate the impact of persistent ZIKV infection on uteroplacental pathology, blood flow, and fetal growth and development. Despite seemingly normal fetal growth and persistent fetal-placenta-maternal infection, advanced non-invasive in vivo imaging studies reveal dramatic effects on placental oxygen reserve accompanied by significantly decreased oxygen permeability of the placental villi. The observation of abnormal oxygen transport within the placenta appears to be a consequence of uterine vasculitis and placental villous damage in ZIKV cases. In addition, we demonstrate a robust maternal-placental-fetal inflammatory response following ZIKV infection." monkey

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Abnormal Development Zika Virus | Zika Virus |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

A 29-year-old pregnant woman infected with Zika virus at 9-weeks gestation in Trinidad presented with one-month of fever, headache, and myalgia with persistent viremia. Significant fetal abnormalities were identified at 14-week ultrasound, which is the earliest ultrasound to describe a severely affected fetus following Zika virus infection to our knowledge."

|

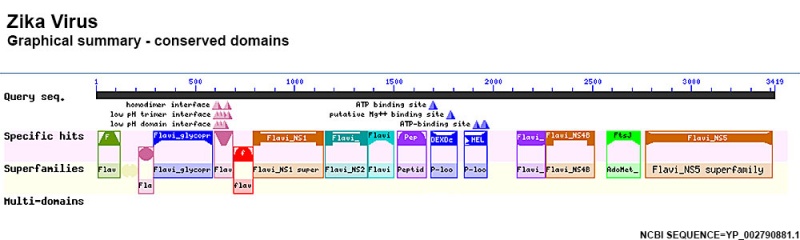

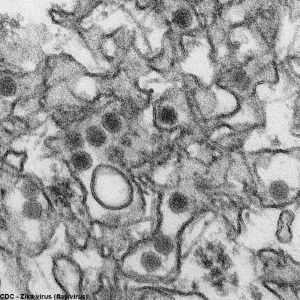

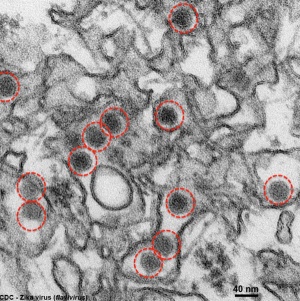

Virus Structure

Virus particles are 40 nm in diameter, with an outer envelope, and an inner dense core. ZIKV is an RNA virus containing 10,794 nucleotides encoding 3,419 amino acids.[18]

| Zika virus | Zika virions (red circles) |

|---|---|

|

|

Lineage: Viruses; ssRNA viruses; ssRNA positive-strand viruses, no DNA stage; Flaviviridae; Flavivirus; Spondweni virus group

| Zika Virus Translation - 3,419 amino acids |

|---|

| MKNPKEEIRRIRIVNMLKRGVARVNPLGGLKRLPAGLLLGHGPIRMVLAILAFLRFTAIKPSLGLINRWGSVGKKEAMEIIKKFKKDLAAMLRIINARKERKRRGADTSIGIIGLLLTTAM AAEITRRGSAYYMYLDR S DAGKAISFATTLGVNKCHVQIMDLGHMCDATMSYECPMLDEGVEPDDVDCWCNTTSTWVVYGTCHHKKGEARRSRRAVTLPSHSTRKLQTRSQTW LESREYTKHLIKVENWIFRNPGFALVAVAIAWLLGSSTSQKVIYLVMILLIAPAYSIRCIGVSNRDFVEGMSGGTWVDVVLEHGGCVTVMAQDKPTVDIELVTTTVSNMAEVRSYCYEA SISDMASDSRCPTQGEAYLDKQSDTQYVCKRTLVDRGWGNGCGLFGKGSLVTCAKFTCSKKMTGKSIQPENLEYRIMLSVHGSQHSGMIGYETDEDRAKVEVTPNSPRAEATLG GFGSLGLDCEPRTGLDFSDLYYLTMNNKHWLVHKEWFHDIPLPWHAGADTGTPHWNNKEALVEFKDAHAKRQTVVVLGSQEGAVHTALAGALEAEMDGAKGRLFSGHLKCRLK MDKLRLKGVSYSLCTAAFTFTKVPAETLHGTVTVEVQYAGTDGPCKIPVQMAVDMQTLTPVGRLITANPVITESTENSKMMLELDPPFGDSYIVIGVGDKKITHHWHRSGSTIGKAFE ATVRGAKRMAVLGDTAWDFGSVGGVFNSLGKGIHQIFGAAFKSLFGGMSWFSQILIGTLLVWLGLNTKNGSISLTCLALGGVMIFLSTAVSADVGCSVDFSKKETRCGTGVFIYNDV EAWRDRYKYHPDSPRRLAAAVKQAWEEGICGISSVSRMENIMWKSVEGELNAILEENGVQLTVVVGSVKNPMWRGPQRLPVPVNELPHGWKAWGKSYFVRAAKTNNSFVVDGD TLKECPLEHRAWNSFLVEDHGFGVFHTSVWLKVREDYSLECDPAVIGTAVKGREAAHSDLGYWIESEKNDTWRLKRAHLIEMKTCEWPKSHTLWTDGVEESDLIIPKSLAGPLSHH NTREGYRTQVKGPWHSEELEIRFEECPGTKVYVEETCGTRGPSLRSTTASGRVIEEWCCRECTMPPLSFRAKDGCWYGMEIRPRKEPESNLVRSMVTAGSTDHMDHFSLGVLVIL LMVQEGLKKRMTTKIIMSTSMAVLVVMILGGFSMSDLAKLVILMGATFAEMNTGGDVAHLALVAAFKVRPALLVSFIFRANWTPRESMLLALASCLLQTAISALEGDLMVLINGFALAW LAIRAMAVPRTDNIALPILAALTPLARGTLLVAWRAGLATCGGIMLLSLKGKGSVKKNLPFVMALGLTAVRVVDPINVVGLLLLTRSGKRSWPPSEVLTAVGLICALAGGFAKADIEMAG PMAAVGLLIVSYVVSGKSVDMYIERAGDITWEKDAEVTGNSPRLDVALDESGDFSLVEEDGPPMREIILKVVLMAICGMNPIAIPFAAGAWYVYVKTGKRSGALWDVPAPKEVKKGE TTDGVYRVMTRRLLGSTQVGVGVMQEGVFHTMWHVTKGAALRSGEGRLDPYWGDVKQDLVSYCGPWKLDAAWDGLSEVQLLAVPPGERARNIQTLPGIFKTKDGDIGAVALDY PAGTSGSPILDKCGRVIGLYGNGVVIKNGSYVSAITQGKREEETPVECFEPSMLKKKQLTVLDLHPGAGKTRRVLPEIVREAIKKRLRTVILAPTRVVAAEMEEALRGLPVRYMTTAVN VTHSGTEIVDLMCHATFTSRLLQPIRVPNYNLNIMDEAHFTDPSSIAARGYISTRVEMGEAAAIFMTATPPGTRDAFPDSNSPIMDTEVEVPERAWSSGFDWVTDHSGKTVWFVPSV RNGNEIAACLTKAGKRVIQLSRKTFETEFQKTKNQEWDFVITTDISEMGANFKADRVIDSRRCLKPVILDGERVILAGPMPVTHASAAQRRGRIGRNPNKPGDEYMYGGGCAETDE GHAHWLEARMLLDNIYLQDGLIASLYRPEADKVAAIEGEFKLRTEQRKTFVELMKRGDLPVWLAYQVASAGITYTDRRWCFDGTTNNTIMEDSVPAEVWTKYGEKRVLKPRWMDA RVCSDHAALKSFKEFAAGKRGAALGVMEALGTLPGHMTERFQEAIDNLAVLMRAETGSRPYKAAAAQLPETLETIMLLGLLGTVSLGIFFVLMRNKGIGKMGFGMVTLGASAWLM WLSEIEPARIACVLIVVFLLLVVLIPEPEKQRSPQDNQMAIIIMVAVGLLGLITANELGWLERTKNDIAHLMGRREEGATMGFSMDIDLRPASAWAIYAALTTLITPAVQHAVTTSYNNYSL MAMATQAGVLFGMGKGMPFMHGDLGVPLLMMGCYSQLTPLTLIVAIILLVAHYMYLIPGLQAAAARAAQKRTAAGIMKNPVVDGIVVTDIDTMTIDPQVEKKMGQVLLIAVAISSAVL LRTAWGWGEAGALITAATSTLWEGSPNKYWNSSTATSLCNIFRGSYLAGASLIYTVTRNAGLVKRRGGGTGETLGEKWKARLNQMSALEFYSYKKSGITEVCREEARRALKDGVAT GGHAVSRGSAKIRWLEERGYLQPYGKVVDLGCGRGGWSYYAATIRKVQEVRGYTKGGPGHEEPMLVQSYGWNIVRLKSGVDVFHMAAEPCDTLLCDIGESSSSPEVEETRTLRV LSMVGDWLEKRPGAFCIKVLCPYTSTMMETMERLQRRHGGGLVRVPLCRNSTHEMYWVSGAKSNIIKSVSTTSQLLLGRMDGPRRPVKYEEDVNLGSGTRAVASCAEAPNMKII GRRIERIRNEHAETWFLDENHPYRTWAYHGSYEAPTQGSASSLVNGVVRLLSKPWDVVTGVTGIAMTDTTPYGQQRVFKEKVDTRVPDPQEGTRQVMNIVSSWLWKELGKRKRP RVCTKEEFINKVRSNAALGAIFEEEKEWKTAVEAVNDPRFWALVDREREHHLRGECHSCVYNMMGKREKKQGEFGKAKGSRAIWYMWLGARFLEFEALGFLNEDHWMGRENSG GGVEGLGLQRLGYILEEMNRAPGGKMYADDTAGWDTRISKFDLENEALITNQMEEGHRTLALAVIKYTYQNKVVKVLRPAEGGKTVMDIISRQDQRGSGQVVTYALNTFTNLVVQLI RNMEAEEVLEMQDLWLLRKPEKVTRWLQSNGWDRLKRMAVSGDDCVVKPIDDRFAHALRFLNDMGKVRKDTQEWKPSTGWSNWEEVPFCSHHFNKLYLKDGRSIVVPCRHQ DELIGRARVSPGAGWSIRETACLAKSYAQMWQLLYFHRRDLRLMANAICSAVPVDWVPTGRTTWSIHGKGEWMTTEDMLMVWNRVWIEENDHMEDKTPVTKWTDIPYLGKRED LWCGSLIGHRPRTTWAENIKDTVNMVRRIIGDEEKYMDYLSTQVRYLGEEGSTPGVL |

Zika History

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-borne flavivirus related to dengue virus first isolated from a rhesus monkey in Zika forest, Uganda (1947), Africa. Transmitted by mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) it was then identified in humans in Nigeria in 1954 and subsequently in South America, Asia and Pacific regions. More recently in Australia from returning travellers.[2]

Documented Outbreaks

- 2007 - Micronesia island of Yap (Pacific)

- 2013 - Micronesia island of Yap (Pacific)

- May 2015 - Brazil (South America)

- October 2015 - Republic of Cabo Verde (Africa)

- November 2015 - Suriname, El Salvador, Mexico, Guatemala, Paraguay, and Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela

Pyriproxyfen

(C20H19NO3) A chemical larvicide used to control mosquito populations, and therefore mosquito-bourns infections. A juvenile hormone analog to insect growth regulator (IGR), inhibiting metamorphosis and embryogenesis in several insects. Suggested that the chemical exposure can act at two levels; firstly the blood-fed females may carry the chemical to the larval habitats, thereby inhibiting adult emergence;secondly that tarsal contact with the chemical may inhibit egg maturation in adult mosquitoes.[19]

- Links: Malaria

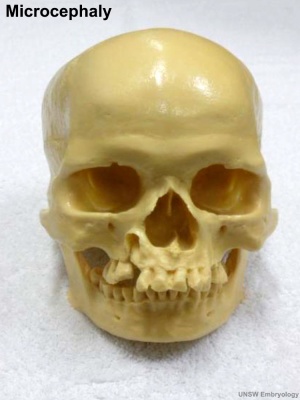

Microcephaly

Microcephaly describes an abnormality of development resulting in a small skull cranium marked by premature fusion of the skull sutures and also under-developed brain.

International Classification of Diseases XVII Congenital Malformations

Congenital malformations of the nervous system (Q00-Q07)

- Q02 Microcephaly Incl.: Hydromicrocephaly Micrencephalon Excl.: Meckel-Gruber syndrome (Q61.9)

- Links: Skull Development | Neural System - Abnormalities | International Classification of Diseases XVII Congenital Malformations

Vision Abnormalities

Some viral infections (herpes and rubella) are known to cause developmental vision abnormalities. A clinical study[17] of infants from Zika infected mothers in Brazil have described vision abnormalities including:

- bilateral ocular lesions

- focal pigment mottling of the retina

- chorioretinal atrophy

- optic nerve abnormalities

- iris coloboma

- lens subluxation

- Links: Vision Abnormalities

References

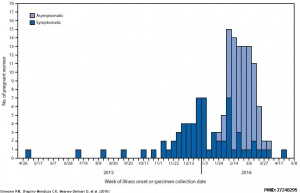

- ↑ Simeone RM, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Meaney-Delman D, Petersen EE, Galang RR, Oduyebo T, Rivera-Garcia B, Valencia-Prado M, Newsome KB, Pérez-Padilla J, Williams TR, Biggerstaff M, Jamieson DJ & Honein MA. (2016). Possible Zika Virus Infection Among Pregnant Women - United States and Territories, May 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. , 65, 514-9. PMID: 27248295 DOI.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Pyke AT, Daly MT, Cameron JN, Moore PR, Taylor CT, Hewitson GR, Humphreys JL & Gair R. (2014). Imported zika virus infection from the cook islands into australia, 2014. PLoS Curr , 6, . PMID: 24944843 DOI.

- ↑ Hamel R, Dejarnac O, Wichit S, Ekchariyawat P, Neyret A, Luplertlop N, Perera-Lecoin M, Surasombatpattana P, Talignani L, Thomas F, Cao-Lormeau VM, Choumet V, Briant L, Desprès P, Amara A, Yssel H & Missé D. (2015). Biology of Zika Virus Infection in Human Skin Cells. J. Virol. , 89, 8880-96. PMID: 26085147 DOI.

- ↑ Besnard M, Lastere S, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau V & Musso D. (2014). Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014. Euro Surveill. , 19, . PMID: 24721538

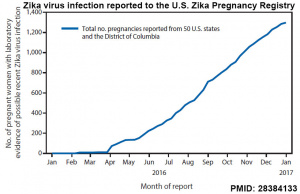

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Reynolds MR, Jones AM, Petersen EE, Lee EH, Rice ME, Bingham A, Ellington SR, Evert N, Reagan-Steiner S, Oduyebo T, Brown CM, Martin S, Ahmad N, Bhatnagar J, Macdonald J, Gould C, Fine AD, Polen KD, Lake-Burger H, Hillard CL, Hall N, Yazdy MM, Slaughter K, Sommer JN, Adamski A, Raycraft M, Fleck-Derderian S, Gupta J, Newsome K, Baez-Santiago M, Slavinski S, White JL, Moore CA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Petersen L, Boyle C, Jamieson DJ, Meaney-Delman D & Honein MA. (2017). Vital Signs: Update on Zika Virus-Associated Birth Defects and Evaluation of All U.S. Infants with Congenital Zika Virus Exposure - U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. , 66, 366-373. PMID: 28384133 DOI.

- ↑ Vianna RAO, Rua EC, Fernandes AR, Dos Santos TCS, Dalcastel LAB, Dos Santos MLB, de Paula PDS, de Carvalho FR, Pache de Faria AO, Almeida PL, Sales LF, Riley LW, de Oliveira SA & Cardoso CAA. (2020). Experience in diagnosing congenital Zika syndrome in Brazilian children born to asymptomatic mothers. Acta Trop. , 206, 105438. PMID: 32165128 DOI.

- ↑ Reyes MM, Ailes EC, Daza M, Tong VT, Osorio J, Valencia D, Turca AR, Galang RR, González Duarte M, Ricaldi JN, Anderson KN, Kamal N, Thomas JD, Villanueva J, Burkel VK, Meaney-Delman D, Gilboa SM, Honein MA, Jamieson DJ & Martinez MO. (2020). Zika Virus Detection in Amniotic Fluid and Zika-Associated Birth Defects. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , , . PMID: 31954155 DOI.

- ↑ Hirsch AJ, Roberts VHJ, Grigsby PL, Haese N, Schabel MC, Wang X, Lo JO, Liu Z, Kroenke CD, Smith JL, Kelleher M, Broeckel R, Kreklywich CN, Parkins CJ, Denton M, Smith P, DeFilippis V, Messer W, Nelson JA, Hennebold JD, Grafe M, Colgin L, Lewis A, Ducore R, Swanson T, Legasse AW, Axthelm MK, MacAllister R, Moses AV, Morgan TK, Frias AE & Streblow DN. (2018). Zika virus infection in pregnant rhesus macaques causes placental dysfunction and immunopathology. Nat Commun , 9, 263. PMID: 29343712 DOI.

- ↑ Moreira-Soto A, Cabral R, Pedroso C, Eschbach-Bludau M, Rockstroh A, Vargas LA, Postigo-Hidalgo I, Luz E, Sampaio GS, Drosten C, Netto EM, Jaenisch T, Ulbert S, Sarno M, Brites C & Drexler JF. (2018). Exhaustive TORCH Pathogen Diagnostics Corroborate Zika Virus Etiology of Congenital Malformations in Northeastern Brazil. mSphere , 3, . PMID: 30089647 DOI.

- ↑ Schwartz KL, Chan T, Rai N, Murphy KE, Whittle W, Drebot MA, Gubbay J & Boggild AK. (2018). Zika virus infection in a pregnant Canadian traveler with congenital fetal malformations noted by ultrasonography at 14-weeks gestation. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines , 4, 2. PMID: 29632700 DOI.

- ↑ A single mutation in the prM protein of Zika virus contributes to fetal microcephaly Science 28 Sep 2017: eaam7120 DOI: 10.1126/science.aam7120

- ↑ Melo AS, Aguiar RS, Amorim MM, Arruda MB, Melo FO, Ribeiro ST, Batista AG, Ferreira T, Dos Santos MP, Sampaio VV, Moura SR, Rabello LP, Gonzaga CE, Malinger G, Ximenes R, de Oliveira-Szejnfeld PS, Tovar-Moll F, Chimelli L, Silveira PP, Delvechio R, Higa L, Campanati L, Nogueira RM, Filippis AM, Szejnfeld J, Voloch CM, Ferreira OC, Brindeiro RM & Tanuri A. (2016). Congenital Zika Virus Infection: Beyond Neonatal Microcephaly. JAMA Neurol , 73, 1407-1416. PMID: 27695855 DOI.

- ↑ Mysorekar IU & Diamond MS. (2016). Modeling Zika Virus Infection in Pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. , 375, 481-4. PMID: 27433842 DOI.

- ↑ de Fatima Vasco Aragao M, van der Linden V, Brainer-Lima AM, Coeli RR, Rocha MA, Sobral da Silva P, Durce Costa Gomes de Carvalho M, van der Linden A, Cesario de Holanda A & Valenca MM. (2016). Clinical features and neuroimaging (CT and MRI) findings in presumed Zika virus related congenital infection and microcephaly: retrospective case series study. BMJ , 353, i1901. PMID: 27075009

- ↑ Driggers RW, Ho CY, Korhonen EM, Kuivanen S, Jääskeläinen AJ, Smura T, Rosenberg A, Hill DA, DeBiasi RL, Vezina G, Timofeev J, Rodriguez FJ, Levanov L, Razak J, Iyengar P, Hennenfent A, Kennedy R, Lanciotti R, du Plessis A & Vapalahti O. (2016). Zika Virus Infection with Prolonged Maternal Viremia and Fetal Brain Abnormalities. N. Engl. J. Med. , 374, 2142-51. PMID: 27028667 DOI.

- ↑ Torjesen I. (2016). Zika virus outbreaks prompt warnings to pregnant women. BMJ , 352, i500. PMID: 26813766

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 de Paula Freitas B, de Oliveira Dias JR, Prazeres J, Sacramento GA, Ko AI, Maia M & Belfort R. (2016). Ocular Findings in Infants With Microcephaly Associated With Presumed Zika Virus Congenital Infection in Salvador, Brazil. JAMA Ophthalmol , , . PMID: 26865554 DOI.

- ↑ Kuno G & Chang GJ. (2005). Biological transmission of arboviruses: reexamination of and new insights into components, mechanisms, and unique traits as well as their evolutionary trends. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. , 18, 608-37. PMID: 16223950 DOI.

- ↑ Ohba SY, Ohashi K, Pujiyati E, Higa Y, Kawada H, Mito N & Takagi M. (2013). The effect of pyriproxyfen as a "population growth regulator" against Aedes albopictus under semi-field conditions. PLoS ONE , 8, e67045. PMID: 23843982 DOI.

Textbooks

- Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Baron S, editor. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. Chapter 55 Togaviruses: Rubella Virus | Chapter 54Alphaviruses (Togaviridae) and Flaviviruses (Flaviviridae)Figure 55-3 Incidence rates of rubella USA 1966-1993

- Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. New York: Garland Science; 2002. Viruses Exploit Host Cell Machinery for All Aspects of Their Multiplication

- Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition. Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al., editors. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2006. Chapter 20Vaccine-preventable Diseases

Reviews

Marano G, Pupella S, Vaglio S, Liumbruno GM & Grazzini G. (2016). Zika virus and the never-ending story of emerging pathogens and transfusion medicine. Blood Transfus , 14, 95-100. PMID: 26674815 DOI.

Articles

Marcondes CB & Ximenes Mde F. (2016). Zika virus in Brazil and the danger of infestation by Aedes (Stegomyia) mosquitoes. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. , 49, 4-10. PMID: 26689277 DOI.

Search Pubmed

Search Pubmed: Zika Virus | Microcephaly

| Environmental Links: Introduction | low folic acid | iodine deficiency | Nutrition | Drugs | Australian Drug Categories | USA Drug Categories | thalidomide | herbal drugs | Illegal Drugs | smoking | Fetal Alcohol Syndrome | TORCH | viral infection | bacterial infection | fungal infection | zoonotic infection | toxoplasmosis | Malaria | maternal diabetes | maternal hypertension | maternal hyperthermia | Maternal Inflammation | Maternal Obesity | hypoxia | biological toxins | chemicals | heavy metals | air pollution | radiation | Prenatal Diagnosis | Neonatal Diagnosis | International Classification of Diseases | Fetal Origins Hypothesis |

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- WHO Factsheet

- NCBI - NCBI Taxonomy | Zika Genome

- Department of Health and Ageing Immunise Australia Program Website

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Abnormal Development - Zika Virus. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Zika_Virus

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G