Abnormal Development - Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| ICD-11 |

|---|

|

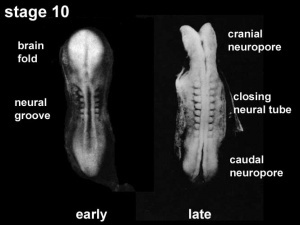

5B5E Folate deficiency - Between days 21 and 27 post-conception, the neural plate closes to form what will eventually be the spinal cord and cranium. Spina bifida, anencephaly, and other similar conditions are collectively called NTDs. They result from improper closure of the spinal cord and cranium, respectively, and are the most common congenital abnormalities associated with folate deficiency. LA00-LA0Z Structural developmental anomalies of the nervous system - LA00.0 Anencephaly LA00.1 Iniencephaly LA00.2 Acephaly LA00.3 Amyelencephaly LA02 Spina bifida - LA02.0 Spina bifida cystica LA02.00 Myelomeningocele with hydrocephalus LA02.01 Myelomeningocele without hydrocephalus LA02.02 Myelocystocele LA02.1 Spina bifida aperta |

Introduction

In 2001, the Australian estimated birth prevalence of neural tube defects was 0.5 per 1,000 births (National Perinatal Statistics Unit). Low maternal dietary folic acid (folate) has been shown to be associated with the development of neural tube defects. In September 2009, mandatory folic acid fortification of bread flour was introduced in Australia.

Research over the last 20 years had suggested a relationship between maternal diet and the birth of an affected infant. Recent evidence has confirmed that folic acid, a water soluble vitamin (vitamin B9) found in many fruits (particularly oranges, berries and bananas), leafy green vegetables, cereals and legumes, may prevent the majority of neural tube defects.

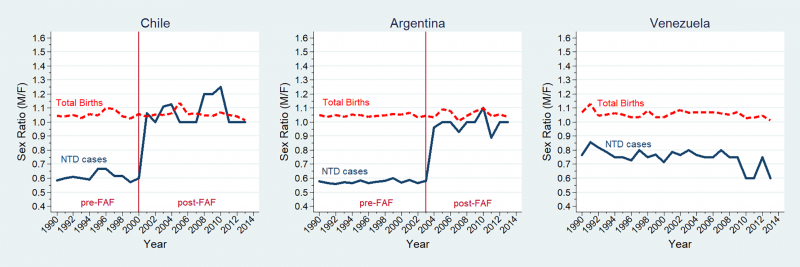

This class of abnormalities was historically more associated with Female infants and a recent study of Latin American countries has identified a substantial decrease in this ratio following folate fortification.[1]

|

|

In the U.S.A., the Food and Drug Administration in 1996 authorized that all enriched cereal grain products be fortified with folic acid, with optional fortification beginning in March 1996 and mandatory fortification in January 1998.

In Australia, from 2009 the mandatory folic acid fortification standard required addition of folic acid to all wheat flour for bread making, with the exception of organic bread, within the prescribed range of 200–300 μg per 100 g of flour.

The March of Dimes Folic Acid Campaign (a major US charity group) has as one of its major objectives to reduce neural tube defects by 30% by 2001 using community programs, professional education, and mass media information.

| Nutrition Links: nutrition | Vitamin A | Vitamin B | Vitamin C | Vitamin D | Vitamin E | Vitamin K | folate | iodine deficiency | neural abnormalities | Axial Skeleton Abnormalities |

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Neural Tube Defect | Spina bifida | Spina bifida cystica | | Spina bifida aperta | Myelomeningocele | Myelocystocele |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

Neural Tube Closure

| <html5media height="360" width="360">File:Neuraltube_001.mp4</html5media> | This cartoon movie shows a dorsolateral view (from the back left side) of the early embryo.

|

Neural Tube Defect Classification

Neural tube defects comprise three distinct conditions: anencephaly, spina bifida and encephalocele. Note that the current ICD10 classification system is being updated to ICD11 that is currently in beta testing status. The data on this page, other than the information table below, is from ICD10 classification.

| ICD-11 LA00-LA0Z Structural developmental anomalies of the nervous system |

|---|

|

| International Classification of Diseases ICD-11 20 Developmental anomalies (beta draft) |

|---|

| ICD-11 Beta Draft - NOT FINAL, updated on a daily basis, It is not approved by WHO, NOT TO BE USED for CODING except for agreed FIELD TRIALS.

Chapter 20 Developmental anomalies, only a few examples of the draft ICD-11 Beta coding and tree structure for "structural developmental anomalies" within this section are shown in the table below. |

| Mortality and Morbidity Statistics - 20 Developmental Anomalies |

Structural Developmental Anomalies

|

| Multiple developmental anomalies or syndromes |

| Chromosomal anomalies, excluding gene mutations |

| Conditions with disorders of intellectual development as a relevant clinical feature |

| LD6Y Other specified developmental anomalies

LD6Z Developmental anomalies, unspecified |

| CD-11 Beta Draft - NOT FINAL, updated on a daily basis, It is not approved by WHO, NOT TO BE USED for CODING except for agreed FIELD TRIALS. |

Australian Statistics

From 13 September 2009, the mandatory folic acid fortification standard requires the addition of folic acid to all wheat flour for bread making, with the exception of organic bread, within the prescribed range of 200–300 μg per 100 g of flour.

A recent 2016 study[6] has shown since fortification:

- Overall decrease in the rate of neural tube defects (NTDs) by 14.4%

- Teenagers the rate of NTDs decreased by almost 55%

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women the rate of NTDs decreased by 74%

An earlier 2011 study[11] looking at the prevalence of neural tube defects before mandatory fortification.

- Women who have one infant with a neural tube defect have a significantly increased risk of recurrence

- 40-50 per thousand compared with 2 per thousand for all births.

- A randomised controlled trial conducted by the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom demonstrated a 72% reduction in risk of recurrence by periconceptional (ie before and after conception) folic acid supplementation (4mg daily).

- Other epidemiological research, including work done in Australia, suggests that primary occurrences of neural tube defects may also be prevented by folic acid either as a supplement or in the diet.

- This has been confirmed in a randomised controlled trial from Hungary, which found that a multivitamin supplement containing 0.8mg folic acid was effective in reducing the occurrence of neural tube defects in first births.

Before mandatory folic acid fortification was introduced:

- mean dietary folic acid intakes for women aged 16–44 years (the target population) in Australia was 108 micrograms (μg) of folic acid per day and in New Zealand was 62 μg of folic acid per day, well below the recommended 400 μg per day.

- there were 149 pregnancies affected by NTDs in 2005 in Australia (rate of 13.3 per 10,000 births) in the three states that provide the most accurate baseline of NTD incidence (South Australia, Western Australia and Victoria), and 63 pregnancies affected by NTDs in 2003 in New Zealand (rate of 11.2 per 10,000 births).

Before mandatory iodine fortification was introduced:

- large proportions of the Australian and New Zealand population had inadequate iodine intakes.

- national surveys measuring median urinary iodine concentration (MUIC) in schoolchildren, an indicator of overall population status, confirmed mild iodine deficiency in both countries.

- The concentration was 96 μg per litre in Australia, and 66 μg per litre in New Zealand, less than the 100–200 μg per litre considered optimal.

- Links: Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects | Iodine Deficiency | Australian Statistics | AIHW - folic acid and iodine

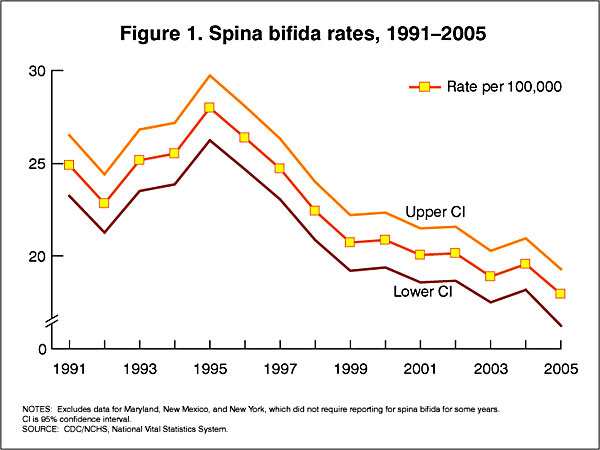

USA Statistics

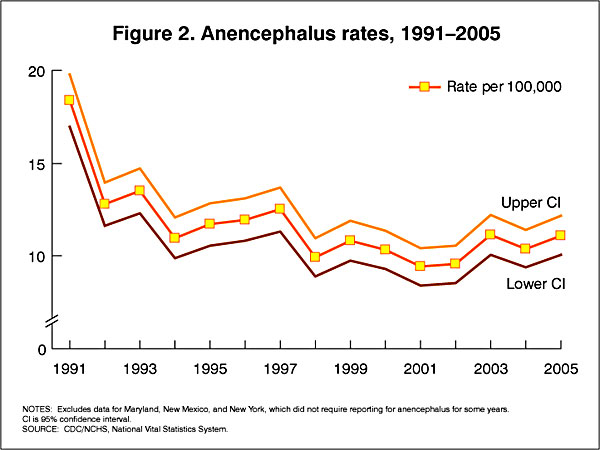

In the U.S.A. the Food and Drug Administration in 1996 authorized that all enriched cereal grain products be fortified with folic acid, with optional fortification beginning in March 1996 and mandatory fortification in January 1998. The data below shows the subsequent changes in anencephaly and spina bifida rate over that period.

Data CDC Report[12]

Latin America Statistics

A recent 2018 study of Latin American countries, has demonstrated a Female association and a substantial decrease in this ratio following folate fortification.[1] In contrast, an earlier 2015 USA study showed no sex association in their population.[13]

Sex ratio changes for NTD cases and total births in Chile, Argentina, and Venezuela (1990–2013).[1]

NTD: neural tube defect; FAF: folic acid fortification; M/F: male/female; Sex ratio (male/female) for neural tube defect cases (full blue line), sex ratio for total births (dashed red line). Sex ratios estimated by multivariate regression models adjusted by hospital.

Potential Risk Factors

| Maternal nutrition | Alcohol use, Caffeine use, low folic acid, Low dietary quality, Elevated glycaemic load or index, Low methionine intake, Low serum choline level, Low serum vitamin B12 level, Low vitamin C level, Low zinc intake |

|---|---|

| Other maternal factors | smoking, maternal hyperthermia, Low socio-economic status, Maternal infections and illnesses (TORCH, viral infection, bacterial infection, fungal infection), maternal diabetes, Pregestational obesity, Psychosocial stress, Valproic acid use |

| Environmental factors | Ambient air pollution, Disinfectant by-products in drinking water, Indoor air pollution, Nitrate-related compounds, Organic solvents, Pesticides, Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| Table data from review[14] (see original review for references) | |

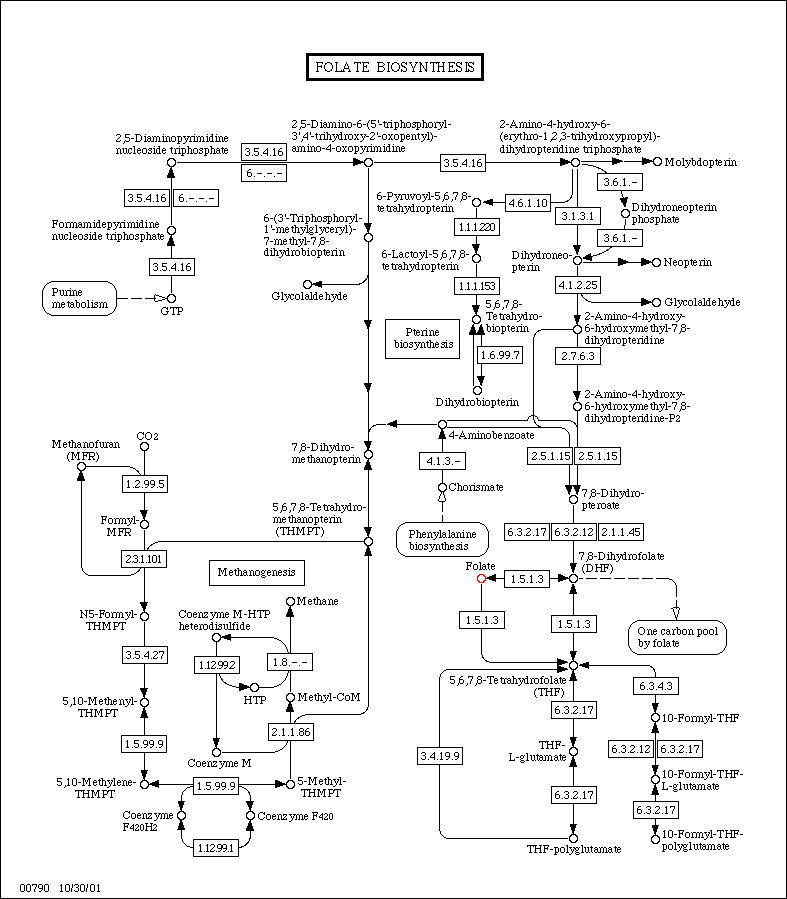

Folate Biosynthesis

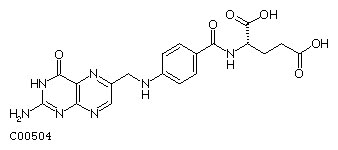

Formula: C19H19N7O6

Alternate Names: Folic acid, Folate, Pteroylglutamic acid

(Data from KEGG)

Folate Supplementation and Other Abnormalities

A recent study of periconceptional folate supplementation using the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (July 2010) identified no statistically significant evidence of any effects on prevention of cleft palate, cleft lip, congenital cardiovascular defects, miscarriages or any other birth defects.[16]

Surgery for Spina Bifida

Fetal Surgery

The neural tube remaining open during fetal development can lead to neural damage through exposure to amniotic fluid and mechanical effects. There are experimental fetal surgical techniques in some countries that allow prenatal repair and perhaps prevent further neurological damage. There are though fetal and maternal risks associated with this surgical procedure.[17] A recent 2014 Cochrane Database study[18] identified that "insufficient evidence to recommend drawing firm conclusions on the benefits or harms of prenatal repair as an intervention for fetuses with spina bifida."

Neonatal Surgery

The surgical repair after birth is a more common procedure.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Poletta FA, Rittler M, Saleme C, Campaña H, Gili JA, Pawluk MS, Gimenez LG, Cosentino VR, Castilla EE & López-Camelo JS. (2018). Neural tube defects: Sex ratio changes after fortification with folic acid. PLoS ONE , 13, e0193127. PMID: 29538416 DOI.

- ↑ Kawakubo-Yasukochi T, Morioka M, Ohe K, Yasukochi A, Ozaki Y, Hazekawa M, Nishinakagawa T, Ono K, Nakamura S & Nakashima M. (2019). Maternal folic acid depletion during early pregnancy increases sensitivity to squamous tumor formation in the offspring in mice. J Dev Orig Health Dis , 10, 683-691. PMID: 31131784 DOI.

- ↑ Gao X, Finnell RH, Wang H & Zheng Y. (2018). Network correlation analysis revealed potential new mechanisms for neural tube defects beyond folic acid. Birth Defects Res , , . PMID: 29732722 DOI.

- ↑ Shi Z, Yang X, Li BB, Chen S, Yang L, Cheng L, Zhang T, Wang H & Zheng Y. (2018). Novel Mutation of LRP6 Identified in Chinese Han Population Links Canonical WNT Signaling to Neural Tube Defects. Birth Defects Res , 110, 63-71. PMID: 28960852 DOI.

- ↑ Li H, Zhang J, Chen S, Wang F, Zhang T & Niswander L. (2018). Genetic contribution of retinoid-related genes to neural tube defects. Hum. Mutat. , , . PMID: 29297599 DOI.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 AIHW 2016. Monitoring the health impacts of mandatory folic acid and iodine fortification 2016. Cat. no. PHE 208. Canberra: AIHW. PDF

- ↑ Hollis ND, Allen EG, Oliver TR, Tinker SW, Druschel C, Hobbs CA, O'Leary LA, Romitti PA, Royle MH, Torfs CP, Freeman SB, Sherman SL & Bean LJ. (2013). Preconception folic acid supplementation and risk for chromosome 21 nondisjunction: a report from the National Down Syndrome Project. Am. J. Med. Genet. A , 161A, 438-44. PMID: 23401135 DOI.

- ↑ Surén P, Roth C, Bresnahan M, Haugen M, Hornig M, Hirtz D, Lie KK, Lipkin WI, Magnus P, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Schjølberg S, Davey Smith G, Øyen AS, Susser E & Stoltenberg C. (2013). Association between maternal use of folic acid supplements and risk of autism spectrum disorders in children. JAMA , 309, 570-7. PMID: 23403681 DOI.

- ↑ Lee MS, Bonner JR, Bernard DJ, Sanchez EL, Sause ET, Prentice RR, Burgess SM & Brody LC. (2012). Disruption of the folate pathway in zebrafish causes developmental defects. BMC Dev. Biol. , 12, 12. PMID: 22480165 DOI.

- ↑ Mallard SR, Gray AR & Houghton LA. (2012). Periconceptional bread intakes indicate New Zealand's proposed mandatory folic acid fortification program may be outdated: results from a postpartum survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth , 12, 8. PMID: 22333513 DOI.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Macaldowie, A. and Hilder, L. (2011) Neural tube defects in Australia: prevalence before mandatory folic acid fortification. Cat. no. PER 53. Canberra: AIHW.

- ↑ CDC Trends in Spina Bifida and Anencephalus in the United States, 1991-2005

- ↑ Michalski AM, Richardson SD, Browne ML, Carmichael SL, Canfield MA, VanZutphen AR, Anderka MT, Marshall EG & Druschel CM. (2015). Sex ratios among infants with birth defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997-2009. Am. J. Med. Genet. A , 167A, 1071-81. PMID: 25711982 DOI.

- ↑ Copp AJ, Adzick NS, Chitty LS, Fletcher JM, Holmbeck GN & Shaw GM. (2015). Spina bifida. Nat Rev Dis Primers , 1, 15007. PMID: 27189655 DOI.

- ↑ Greene ND, Stanier P & Copp AJ. (2009). Genetics of human neural tube defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. , 18, R113-29. PMID: 19808787 DOI.

- ↑ De-Regil LM, Fernández-Gaxiola AC, Dowswell T & Peña-Rosas JP. (2010). Effects and safety of periconceptional folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev , , CD007950. PMID: 20927767 DOI.

- ↑ Adzick NS. (2013). Fetal surgery for spina bifida: past, present, future. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. , 22, 10-7. PMID: 23395140 DOI.

- ↑ Grivell RM, Andersen C & Dodd JM. (2014). Prenatal versus postnatal repair procedures for spina bifida for improving infant and maternal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev , , CD008825. PMID: 25348498 DOI.

Reviews

Veenboer PW, Bosch JL, van Asbeck FW & de Kort LM. (2012). Upper and lower urinary tract outcomes in adult myelomeningocele patients: a systematic review. PLoS ONE , 7, e48399. PMID: 23119003 DOI.

Eichholzer M, Tönz O & Zimmermann R. (2006). Folic acid: a public-health challenge. Lancet , 367, 1352-61. PMID: 16631914 DOI.

Tamura T & Picciano MF. (2006). Folate and human reproduction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. , 83, 993-1016. PMID: 16685040

Wen SW & Walker M. (2005). An exploration of health effects of folic acid in pregnancy beyond reducing neural tube defects. J Obstet Gynaecol Can , 27, 13-9. PMID: 15937577

Articles

Giordan E, Bortolotti C, Lanzino G & Brinjikji W. (2018). Spinal Arteriovenous Vascular Malformations in Patients with Neural Tube Defects. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol , 39, 597-603. PMID: 29284599 DOI.

Molloy AM. (2002). Folate bioavailability and health. Int J Vitam Nutr Res , 72, 46-52. PMID: 11887752 DOI.

Daly LE, Kirke PN, Molloy A, Weir DG & Scott JM. (1995). Folate levels and neural tube defects. Implications for prevention. JAMA , 274, 1698-702. PMID: 7474275

Smithells RW, Sheppard S & Schorah CJ. (1976). Vitamin deficiencies and neural tube defects. Arch. Dis. Child. , 51, 944-50. PMID: 1015847

Leck I. (1977). Folates and the fetus. Lancet , 1, 1099-100. PMID: 68194

Search PubMed

Search Bookshelf: Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects | Folic Acid

- Folic Acid Supplementation for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects An Update of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

- Screening for Neural Tube Defects— Including Folic Acid/Folate Prophylaxis Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2nd Edition: 1996

Search Pubmed: Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects | Folic Acid

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- Australia Department of Health Nutrition and Healthy Eating Trends in Neural Tube Defects in Australia

- See also the NHMRC Publication Dietary Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects

- National Perinatal Statistics Unit

- Australian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics

- Australian Nutrition Foundation

- CSIRO Human Nutrition

- Food, Nutrition & Health Information - Centre for Advanced Food Research

- Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health (USA)Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Folate

- Foodwatch

- Healthy Eating, Healthy Living

- AIS Sport Nutrition - information from the Australian Institute of Sport. Supplies nutrition research, a question-and-answer section, publications, and other resources.

- America's Eating Habits - a report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's economic research service. Covers dietary recommendations, health claims in food advertising, reality about cholesterol, and various other topics.

- British Nutrition Foundation - an organization that works with academic, private, and public groups on nutrition. Includes nutrition education, facts, news, and publications.

- Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition - a repository of links relevant to all manner of food issues, including food safety. Emphasizes FDA regulations and related research programs.

- Nutrition.gov - a collection of information and links to other sites on food safety, food programs, and federally funded research centers.

- Nutrition.org - site of the American Society for Nutritional Sciences. Features an encyclopedia that summarizes food sources, diet recommendations, and deficiencies for a number of macro- and micronutrients.

- Nutrition Navigator - a guide to nutrition websites reviewed and rated by Tufts University nutritionists. Supplies news and sections arranged by topic.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture

- Children's Nutrition Research Center

- Facts about the DASH Diet

- Healthfinder Kids

- Interactive Healthy Eating Index

- National Dairy Council

- Nutrition Explorations

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Abnormal Development - Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Folic_Acid_and_Neural_Tube_Defects

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G