Book - Contributions to Embryology Carnegie Institution No.24

The Developmental Alterations in the Vascular System of the Brain of the Human Embryo

By George L. Streeter with five plates and twelve text-figures (1921).

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

--Mark Hill 12:02, 29 March 2011 (EST) This article was first published in 1921.

- Links: Carnegie Institution of Washington - Contributions to Embryology | Embryonic Development | Neural System Development

Introduction

One of the most striking features in the development of the blood-vessels of the head is the clear way in which they demonstrate the embryological principle of what may be termed integrative development. It is quite evident that the vascular apparatus does not independently and by itself "unfold" into the adult pattern. On the contrary, it reacts continuously in a most sensitive way to the factors of its environment, the pattern in the adult being the result of the sum of the environmental influences that have played upon it throughout the embryonic period. We thus find that this apparatus is continuously adequate and complete for the structures as they exist at any particular stage; as the environmental structures progressively change, the vascular apparatus also changes and thereby is always adapted to the newer conditions. Furthermore, there are no apparent ulterior preparations at any time for the supply and drainage of other structures which have not yet made their appearance. For each stage it is an efficient and complete going-mechanism, apparently uninfluenced by the nature of its subsequent morphology.

With these factors in mind, one can better understand the architectural arrangements of the vascular system of the head that appear in different periods of development. In the primordial or precirculatory period the vessels that then exist are engaged principally in growth and in the elaboration of a plexus, and their form then is little influenced by conditions that would favor the circulation of the contained fluid. As the circulatory flow of the blood becomes established we find that the vascular plexus responds by conforming to the hydrodynamic requirements, becoming adequately adapted to the form of the neural tube as then existing, with favorably situated aortic feeders and simple and direct drainage channels. As the brain becomes more complicated, and as the skull-membranes form, there occur, step by step, the necessary adaptations on the part of the bloodvessels. Finally, when the permanent form is attained, the vessels lose their transitory character and develop permanent and more highly differentiated walls, properly

suited to the adult functional requirements.

It is possible to subdivide the development of the blood-vessels of the brain into five successive periods, each showing special adaptations to their changing environmental conditions. To faciUtate the description of this process an arbitrary order of that kind will be adopted in this paper. During the first of these five periods there are established the primordial endothehal blood-containing channels, which are neithei arteries nor veins, but constitute the source from which all the arteries, veins, and capillaries of the brain are derived. These primordial bloodvessels lie bilaterally close along the brain-wall, at first either in the form of a single, slender, longitudinal tube, as seen along the hindbrain, or a plexiform space as seen near the forebrain and midbrain. Soon after the primordial vessels are estabUshod, endothelial buds sprout from their walls and in conjuurtion with them form an irregular endothelial vascular mcshwork which tends to spread over the surface of the brain-wall, especially in the region of the forebrain and midbrain. There is thus formed a plexiform system which constitutes a germinal bed of endothelium rather than a circulatory apparatus.

During the second developmental period the primordial blood-vessel plexus of the head slowly resolves itself into veins, arteries, and capillaries, and becomes

architecturally suited to the circulatory flow of the blood. That portion of the plexus which lies against the brain spreads out as a flattened capillary sheet, conforming everywhere to the shape of the brain-wall and its attached ganglia and sense-organs. The more superficial part of the plexus develops a coarser mesh and forms larger channels, which tend to unite into continuous trunks and gradually, by virtue of their commimications, can he recognized as definite arteries and veins. The intermediate loojis of the plexus maintain the anastomosis between the deep capillary sheet and the more superficial trunks, forming tributaries of the veins and branches of the arteries. The second period thus establishes the primary type of the circulation of the head, in which there is a capillary bed, fed by arterial branches from the aortic system and drained bilaterally by a continuous venous trunk which extends back to the venous end of the heart.

The third period is inaugurated by the differentiation of the membranous skull, the dura mater, and the arachnoid-pial membranes. As a result of this stratification of the tissues of the head, the more ventral of the anastomosing channels that connect the deep capillary plexus with the superficial vessels become closed off and there is a general separation or cleavage of the vessels immediately surrounding the brain-wall from those belonging to the membranous skull and its coverings. This process begins at the base of the skull and extends bilaterally upward toward the middle line of the vault, in which region the communications between the deeper and more superficial systems are to some extent maintained. In this way the cerebral vessels are gradually separated from the dural vessels and in a similar manner the superficial vessels of the head become isolated by the laying down of the primordium of the membranous skull, after which their course of development is quite indejjendent of that of the dural and cerebral systems.

By the time the third period is well under way it is overlapped by the fourth period, under which we include the remarkable series of adjustments in the arrangement of the blood-vessels, in adaptation to the developmental alterations in the form, size, and condition of the structures of the head region. The brain is one of the chief factors in this process. The marked change in its form, and especially the prolonged relative growth of the cerebral hemispheres, render necessary a continuous series of alterations in the blood-channels that extend far into the late fetal stages. In the earlier stages a fundamental change results from the growth of the labyrinth and its cartilaginous capsule, whereby a mechanical oltstruction is introduced that results in the obhteration of a considerable part of the largest vein of the head. This is compensated for by a new channel which takes a more dorsal course, and which eventually forms the sigmoid portion of the lateral sinus.

Finally, under the fifth period we would include the late histological changes in the walls of the vessels that convert them into the adult arteries, veins, and the various types of sinuses. These histological factors, however, are not considered in the present paper and are merely mentioned to complete the sequence, as they have no determining influence on the phenomena of the preceding four periods.

The observations that are reported are chiefly concerned with the third and fourth developmental periods; that is, after the primary circulation of the head is established and during the cleavage and adjustmental stages. A review, however, will be made of the liistory of the vascular system of the head previous to that time, which will be based in large part on the important observations of Evans (1909, 1912) and Pabin (1915, 1917a, 1917b). The study of the development of the vascular system of the head of the human embryo was initiated in this laboratory by Professor Mall (1905). Later I continued the same investigation and reported (Streeter, 1915) some of the features of the adaptive metamorphosis of the dural veins. In the present paper I shall include much of the same subject-matter and incorporate with it further observations made on additional material, thus making it possible to treat the general subject more completely and to demonstrate the relations of the dural veins to the principal arteries of the head.

Content to be added----

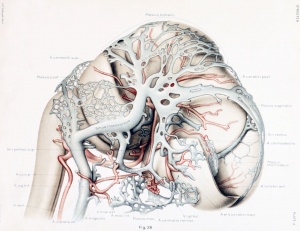

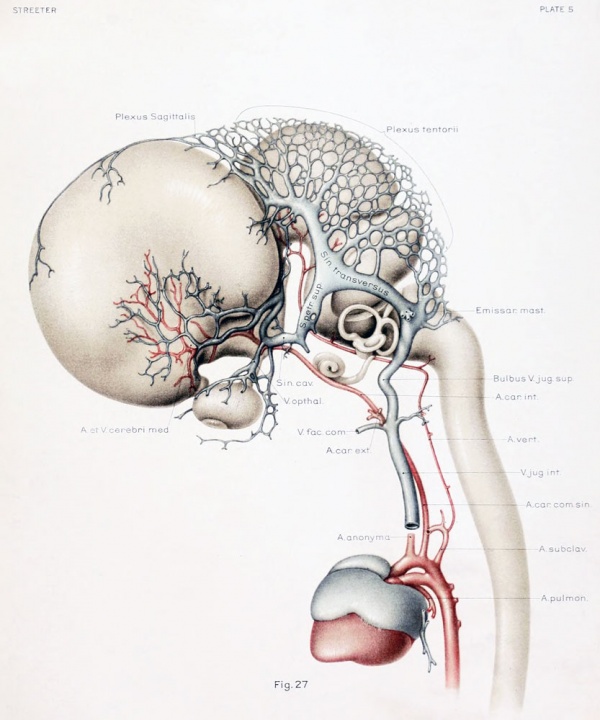

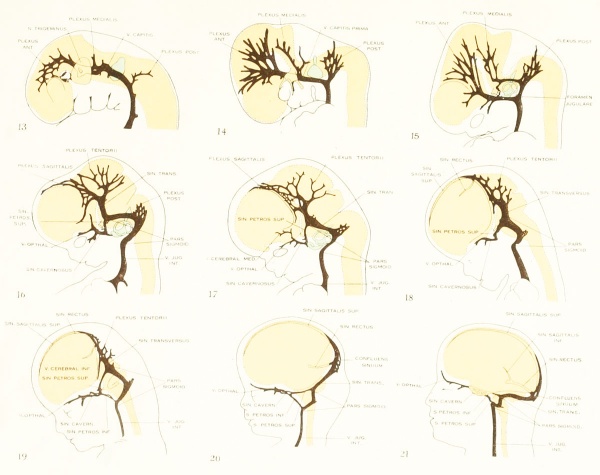

Explanation of Plates

Plate 1

|

Simplified profile drawings of the dural veins, showing the manner in which they adapt themselves to the growth and change in form of the brain in human embryos from 4 mm. to birth.

|

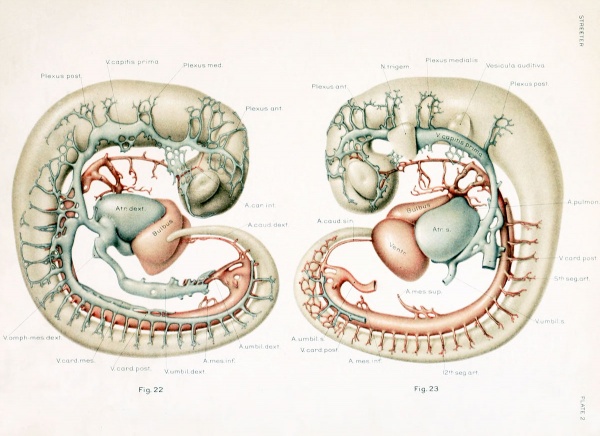

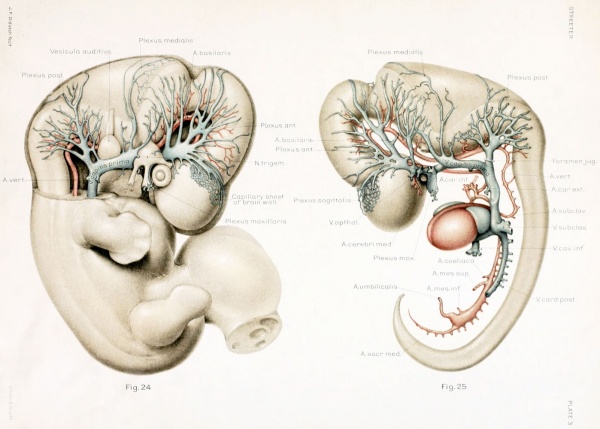

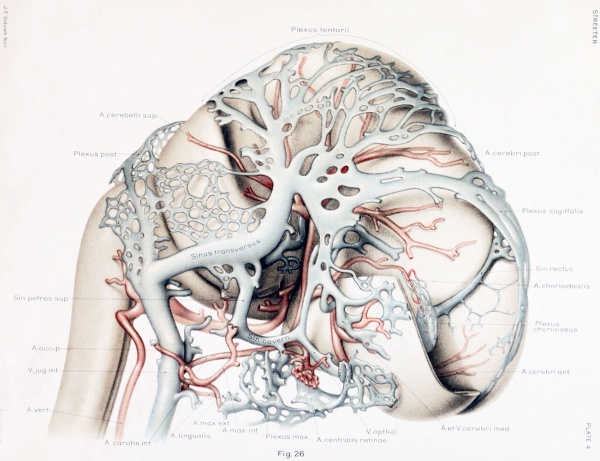

Plate 2

Plate 3

Plate 4

Plate 5

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, May 1) Embryology Book - Contributions to Embryology Carnegie Institution No.24. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_Contributions_to_Embryology_Carnegie_Institution_No.24

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G