Paper - The Disappearance of the Precervical Sinus

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Frazer JE. The disappearance of the precervical sinus. (1926) J Anat. 61(1): 132-43. PMID 17104123.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

The Disappearance Of The Precervical Sinus

By J. Ernest Frazer, F.R.C.S. Professor of Anatomy in the University of London.

J Anat. 1926 Oct; 61(Pt 1): 132–143.

There is much vagueness about the accounts given of the precervical sinus in the human embryo. In most cases the works dealing with the subject record its existence and satisfy themselves with the general assertion that it closes early and disappears.The general belief seems to be that there is fusion between the second external arch and the hinder and lower border of the sinus, so that this is rapidly reduced to an ectodermally lined cyst, opening on the surface by a drawn-out duct, and having the third and fourth arches and external grooves in its floor, with the second "external pharyngeal duct" opening into the neck of the cyst: this idea is apparently founded on Rabl's work on the mole, but the books of reference do not say much about the matter. This conception fits in with the current notions about. bronchiall remnants" in the neck, and the present writer, among others, was content to take it as practically correct, for it seemed to agree well enough with what was noticed incidentally when working on questions connected with the development of the pharynx and its derivatives. Recently, however, he has had reason to go into the matter directly, and the unexpected results obtained in this investigation seem worthy of consideration in full. It was found, as will be shown in this paper, that the sinus does not close at all in the sense usually understood, that the very small external fourth arch is covered in, but the third arch remains on the surface of the neck,and that no fusion normally occurs between the second arch (except perhaps at its upper part) and the structures behind it. Failure of these results to meet the seeming needs of the clinical pathologist, although regrettable, do not constitute any valid argument against them, derived as they are from careful study of normal embryos in good condition; nevertheless, some consideration of the abnormal conditions that are not so rarely found in the neck is certainly desirable, and a few words about some points on this side of the question are contained in a short addendum to the paper.

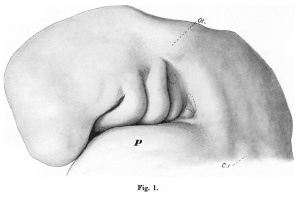

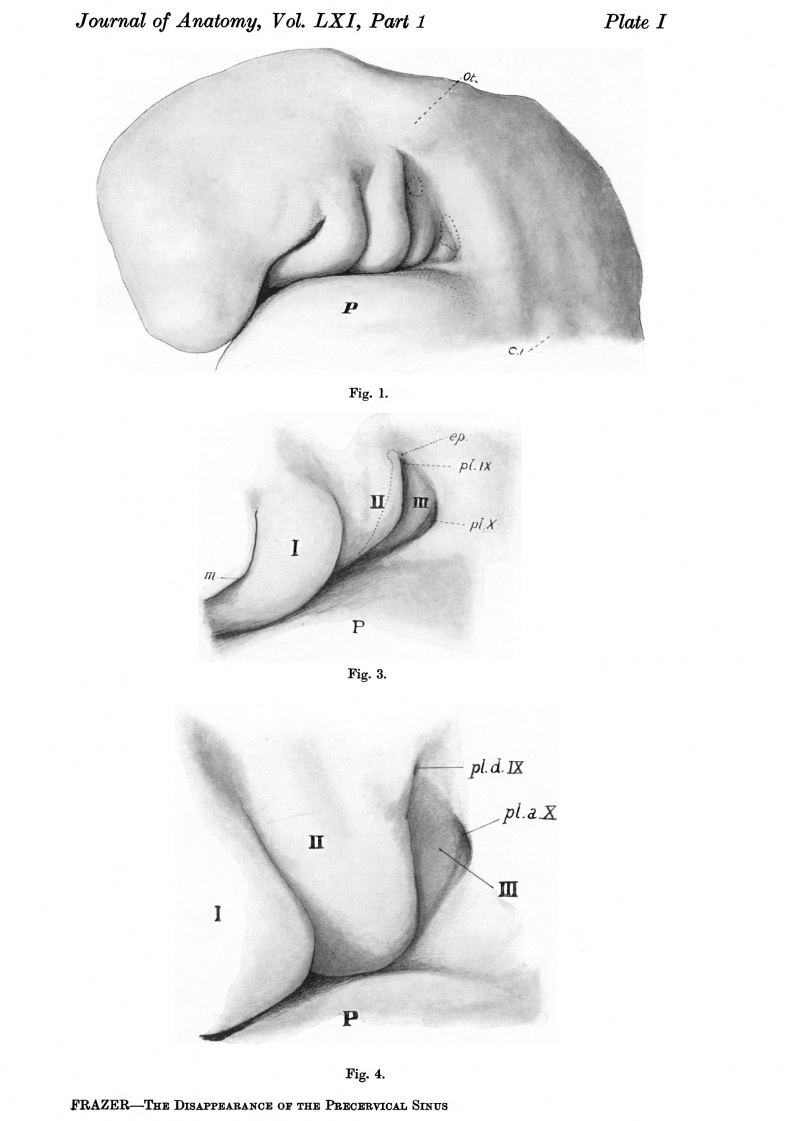

The precervical sinus, a result of the disproportionate size and growth of the outer pharyngeal arches,begins to show on the surface at an early stage. Fig.1 (PI.I), the head of an embryo of less than 5 mm. in total length, gives a very good idea of this early appearance of the sinus, and of its boundaries. The third and fourth arches are visible in a triangular area, slightly depressed, in front of which the second arch is prominent and its groove very evident. Above and behind is a clearly defined broad area, especially well marked behind. The pericardium is below the sinus, but does not form its lower boundary directly: this is made by a clearly seen epipericardial ridge, which is continuous behind with the caudal boundary, and disappears from view, in front, below the lowest visible part of the third arch. The upper, hinder, and lower boundaries are thus continuous with each other round the field of the sinus, and require more particular examination.

A definite groove or depression separates the upper and hinder boundaries from the sinus field, and it is to be noted that the upper part of the second arch is clear, and is not continuous with the upper boundary: the upper end of the second groove comes in between them.This limiting region belongs to the area of paraxial mesoderm. It is continuous above with the bed of paraxial mesoderm in which the otocyst(Ot.)is buried: lower down, where it makes the clearly defined hinder margin of the sinus, it is composed of cell masses derived from myotomic structures, and is apparently in series with the myotomic ventral down growths to be found in the body wall. The first cervical myotome is indicated(C.1) in the figure, and,in line above this,are indefinite suggestions of continuation of the series upwards. Examination of sections shows that these last are indeed myotomic in structure, and have a clearer division into blocks than is apparent on the surface. Cells derived from each of these blocks are found extending into the prominent caudal border of the sinus, making a thick mass lying in a caudo-ventral disposition: the resulting collection of cells shows some slight indication of segmental arrangement (better marked at a later stage) but no sign of this is to be found on the surface. They extend to the pericardium and limb bud, which is not seen in the figure.

The epipericardial ridge, the lower boundary of the sinus field,is composed of cells continuous with and presumably derived from the anterior and deeper parts of these myotomic outgrowths: hence the continuity of this ridge with the caudal boundary of the field. The tract of cells forming the ridge passes forwards and inwards, below and internal to the lower end of the third arch, then internal to the inner and lower end of the second arch: here the tracts of each side lie together, and thence pass into the substance of the mandibular arch, where they become continuous in later stages with the rudiments of the tongue muscles. The hypoglossal nerve is not traceable beyond its origin in the embryo represented in fig.1, but is found a little later in the ridge with the cell tract. The ridge connects the arches with the pericardium as far forward as the level of the second arch; it rests below on the pericardium, and is only separated by a shallow groove from the arches lying above it.

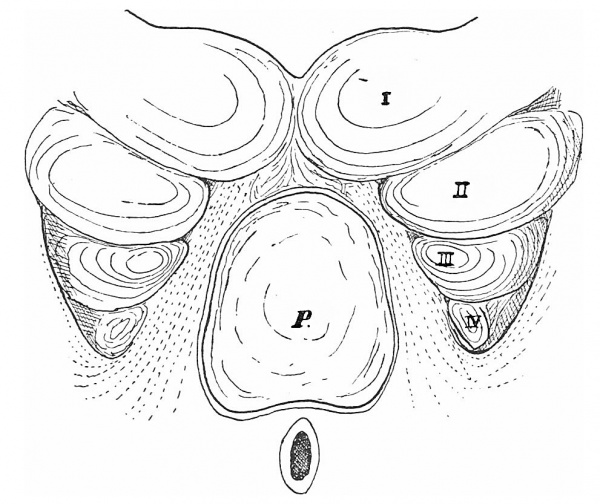

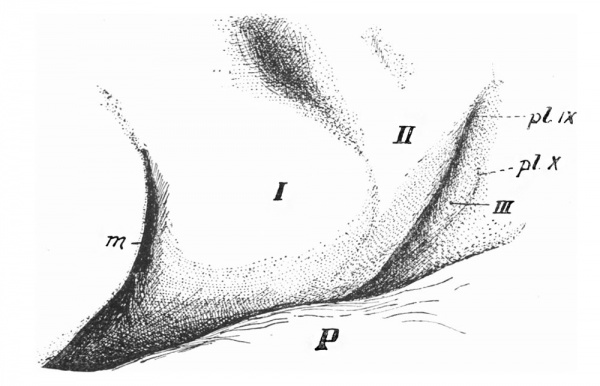

The relations between pericardium, epipericardial ridge, and outer pharynlgeal arches can be understood from fig. 2, which gives a view from below of the region after removal of the pericardial projection: the arches and in fact the whole region are represented as flattened to some extent. The pericardial roof, where it is joined to the neighbouring tissues, is retained. The epipericardial ridge on each side is indicated by interrupted lines lying between the arches and the pericardium. It is seen that, with the exception of the first, the external arches do not meet their fellows in the middle line, being separated by ridges and pericardium: it may be said at once that they never do meet their fellows in the middle line, the ridge areas and (at first) the pericardium intervening. As the pericardium acquires a more caudal position relative to the arches, the enlarged ridge-tracts come together in front of it, and a central area still separates the remnants of the regions of the arches on each side from each other.

It is to be observed that the ridge-tracts pass internal to the ventral or inner ends of the second and third arches, but in front of this sink into the Before leaving the early stage shown in fig. 1 it is necessary to note that there is a fairly broad strip of thickened ectoderm, the placodal area, running from before backwards along the upper ends of the arches and grooves. Without advancing any opinion about the value of this area, it can be pointed out that in certain parts its cells are certainly continuous with the cellular masses of nerve rudiments. Two of these parts, in connection respectively with the rudiments of the IXth and Xth nerves, are of importance from the present point of view: they are indicated by dotted lines in fig. 1, while the rest of the strip, not associated directly with nerve rudiments. is not shown. The IXth placode is at and above the upper end of the third arch, some little distance down the side of the long second groove; the Xth placodal area, perhaps more extensive than represented in the figure, covers the upper and greater part of the fourth arch, a small area above it, and the whole depth of the paraxial border in this part.

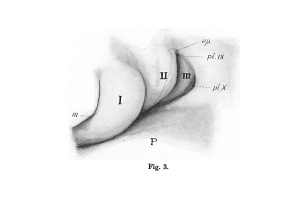

The area of the precervical sinus deepens as the result of rapid growth of its paraxial boundaries, the second arch also becoming more prominent for a time. Fig. 3 (P1. I), from an embryo of 8 mm., gives an illustration of the earlier consequences of this growth. The main feature is a rapid increase in paraxial mesodermal thickness, which thus comes to overlap and fold in the placodal areas. As a result placodal area IX is now lying at the bottom of a short recess opening into the upper part of the apparent second groove, while the turning in of the large Xth area has led to practically the whole fourth arch being hidden in a similar but larger recess. Between the two recesses the paraxial thickening bulges above, but does not cover or invade, the area of the third arch.

Fig. 2. Semi-schematic view of the lower aspect of the pharyngeal region, the pericardium having been removed, save for its roof. I, II, III, IV, pharyngeal arches, external; P, roof of pericardium. The whole region is somewhat flattened out to show the relations. substance of the mandibular arch, which is the only one completely joined in the middle line.

At the point ep. in fig. 3, where the growing paraxial region is apposed to the long second arch, there is a very small fusion between these parts on the other side in this embryo; it could not be recognised with certainty on the left side. It suggests a fusion, no doubt associated with the growth which causes the overlapping of the placode here, between the paraxial swelling and the upper part of the hinder border of the second arch.

The upper portion of the second groove, above the level of the placode, is now only represented by a shallow depression. This part has been practically obliterated, but not, it would appear, by any process of fusion: the condition found in an embryo of 7 mm. supports this opinion. In this specimen the paraxial growth is overhanging the placode but has not yet begun to turn it in, and the posterior border of the second arch, clearly cut opposite the placode, becomes shallow and indefinite above this in the region of paraxial thickening. It seems that the level of the depression behind the upper part of the second arch, as far down as the placodal inturning, is simply raised and the edge of the arch made indefinite by the growth of the mass behind it, without any meeting and fusion of the two prominences. If this view of the matter is correct, the very small fusion noticed on one side in the 8mm. embryo may be nothing but a deceptive appearance, or may be an indication of a definite little point of suture between the arch and the overhanging lip of the growth covering in the placodal area. The fusion, however, if it does occur at all, does not go any further: the conditions shown in fig.3, in fact, may be said to indicate already what will be the extent of overlapping in the region of the sinus brought about by the surrounding growth.

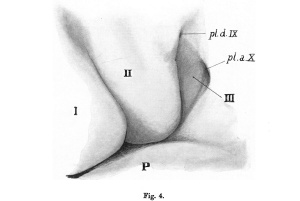

The sinus field in an embryo of 10mm. is shown in fig.4 (P1.I). The placodal areas are now so completely covered and folded in that each is at the enlarged end of a deep pocket or tunnel opening on the surface. The conditions are essentially as in fig. 3 so far as the positions of the openings of the tunnels are concerned, the only difference being in their sizes: they are both smaller, and lead into deeper recesses, that of X being so deep that the fourth arch is no longer actually visible in its floor as in the earlier specimen. The third arch stands out clearly, and is not overlapped or covered in any way by the formation of these placodal pockets.

It is obvious that the changes going on are concerned mainly with the closing in of the placodal areas. The process is fairly rapid, and by the time that the embryo reaches a length of 12 mm. the areas are shut off from the surface. Intervening stages simply show the intermediate conditions.

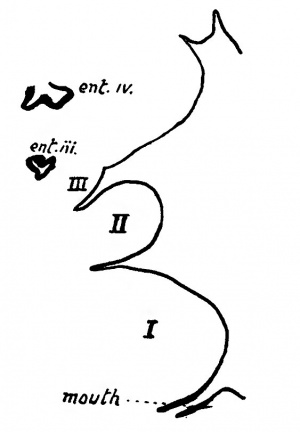

Fig.5 gives the surface view of the region in an embryo barely 12mm. in length. In this specimen the two placodal areas form buried cysts (cervical vesicles)related to the corresponding ganglia. Cyst X is connected with the surface still by a definite epithelial strand, enclosing a lumen at its inner end, but otherwise apparently a solid thin cord: placodal cyst IX has lost its connection with the surface, but the line formerly taken by this can, I think, be made out. The duct of this cyst disappears apparently about the 11 mm. stage. The position of these two points of final attachment to the ectoderm in the 12mm. embryo can be seen in the figure:the third arch lies, as before, between them, bounded behind by a very shallow but definite groove, and the condition is as in the 10mm. embryo with the exception that the two open ducts have been closed.

Fig. 5. Left side of region in an embryo of 12 mm. showing the structures behind the mouth, m. I, II, III, pharyngeal arches; P ,pericardium. Ectodermal connections with placodal cysts indicated at pl.IX,pl.X.

This terminates the history of the surface changes in this region, so far as the sinus is concerned. No further overlapping takes place, nor is it to be expected. The only things that have been covered in in the field of the original sinus are those parts that were related to placodes, and the greater portion of the field-that is, the third arch-remains exposed. The vesicles disappear almost immediately after their connections with the surface have gone.

In this account of the changes taking place in the region of the sinus in the human embryo, the placodal areas certainly stand forward most prominently as the structures that are mainly affected: they are covered in and sink deeply, and they are the only areas really in which any marked change is brought about,in this or in any other way. It is allowable, of course,to refer their sinking to their connection with nerves which remain in relation with the visceral wall, but one cannot help feeling that there is more in the matter than a mere physical attachment, and that some explanation is required for their persistent existence as open vesicles with "ducts," and for their disappearance when these channels close, as well as for the general fact that the yseem to be the centre of the changes which go on in the region under consideration. I can offer no suggestions on the matter: no definite contributions to the nerves were made out, although there was certainly the appearance of contribution to the sheaths of the nerves, but the sections had not been prepared in any special way to show such processes ifthey existed. One recalls the formation of the organ of Pinkus, or Muller, permanent or temporary placodal derivatives of unknown function: it is possible that the placodal cysts of the present description may represent remnants of parallel formations more caudally situated, but in any case the same unsatisfactory ignorance of possible function must remain.

The disappearance of the third arch as a projection on the surface is easily understood. This arch is concerned in the formation of many important structures in and about the pharynx, but not on the surface, and its appearance on the surface is only the result of its growth and condensation when the wall of the pharynx is relatively thin. As the wall thickens the active growth of the arch, being concentrated in its deep portion, quickly loses its influence on the surface form, and by the time the embryo reaches 12 mm. in length, or even before this, any direct continuity between the surface arch and the deep arch structures cannot be made out in sections: shortly after this the absence of any sort of resistant connection between the two is emphasised by the change in position of the arterial stemsinthisregion,butthis change has really begun much earlier and indicates a correspondingly earlier divorce between the internal arch and its external manifestation.

Under these circumstances of failure of the continued action of the growth originally producing it, it is to be expected that the external arch would tend to disappear, and it does this largely by the simple process of flattening. The prominence of an arch depends, however, not only on its own size, but equally on the depths of the grooves that limit it, and this is seen very well in the case of the third arch.

The second groove persists because it is the transverse line of flexure of the neck, whereas the third groove, not very deep in the early stages, begins to get shallow very soon, so that at the 10mm. stage, for example, the arch is an upstanding structure seen from the front (fig. 6) owing to the depth of the second groove, whereas it is separated from the structures behind it by a very shallow remnant of the original third external groove. in the 12mm. stage this inequality in accentuation of the margins of the arch is even more striking, and it is evident that the hinder groove is on the point of disappearing, leaving the surface of the arch continuous with that of the

adjoining area.

The grooves were carefully examined with a view to ascertaining the mode of disappearance, so far as this could be done: in this connection I would like to express my thanks to Dr Gladstone for the loan of a couple of embryos, which I examined in addition to my own. The groove between the first and second arches is closed by epithelial fusion at about 11 mm., but in no other part was such method of occlusion to be made out in anyway. No epithelial remnants were found at any stage, or in any position, in relation with the other grooves, except of course in the cases of the "placodal ducts."

No definite statements can be made about the modus operandi of closure of these channels leading from the placodal cysts, except that they gradually increase in length and decrease in calibre, and in doing so show no sign whatever of any epithelial destruction. Perhaps this really expresses the matter, for it seems possible that increasing thickness and depth of the growing tissues round them would lead to these two changes taking place simultaneously: at any rate the sections failed to afford me any more complete explanation of the changes, and the matter must be left here. The final separation from the surface may be brought about by destruction of the elongated epithelial strand, for what might well be remnants of such a strand could be found in association with placodal cyst IX at 12 mm., although I have not so far been able to recognise at a later stage any remains that might have been associated with the other vesicle.

The flattened external third arch, left exposed in the way described, forms a part of the surface of the neck, but the area made by it can only be arrived at by inference. In an embryo of 13.5 mm. it is possible to find what seem to be the limits of the arch,but afterthis, although the definite line of transverse flexure is undoubtedly the second groove, there is no way of distinguishing with any certainty at all the caudal boundary of the third arch. At this stage the rudimentary condensation of the clavicle can be recognised, lying in the third arch area just caudal to the transverse flexure line. The constituent tissues of the original epipericardial ridge lie ventral and internal to the third arch area, and can be traced forward to the hyoid rudiment: it is interesting to observe that there is definite continuity between these early muscle fibres and those in the tongue, passing on the ventral side of the hyoid, although most of these fibres below the third arch area end at the hyoid rudiment. Traced backwards, these fibres pass behind the arch area, lying deep to the sternomastoid, which is now definitely distinct from the deeper structures of the caudal border of the sinus field. There is here, evidently, little more than the differentiation of the tissues in and surrounding the caudal border of the sinus field: there is no alteration in their arrangement, but the appearance of the clavicular and hyoid rudiments afford new standards by which one may appreciate further changes.

The clavicular condensation reaches the middle line just caudal to the flexure line, where it is continuous with the episternal thickening ventral to the upper part of the pericardium: it extends upwards and outwards from this. It is obvious, then, that this condensed region near the middle line is in close relation with the epipericardial structures, which can now be referred to as the infrahyoid muscles, and by the time the embryo reaches a length of 16mm. the muscle sheet is attached to the skeletal elements.The sections give the impression that the enlarging end of the clavicle has grown into the muscle layer, but whether this is so or not, the attachment of the muscle sheet here is quite evident. The clavicle is practically in the same position as before, and the neck, from the adult point of view, is as yet hardly

inexistence.

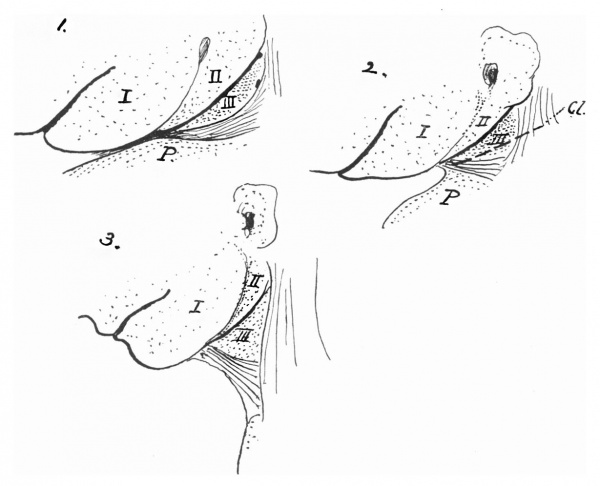

Fig. 7. Three schemes to show the situation acquired by the third arch as the neck forms. Cl. gives the general position and line of the clavicle. Other references as before.

We have here, however, the foundation of the neck, with certain fixed points, and its formation in the second and third months runs the course that might be expected from the facts already stated. it is not necessary to add to the length of this paper by going into the details of the growth, and it will be enough for present purposes to indicate their general results in the accompanying schemes (fig. 7). The first figure shows the general arrangement of the embryonic parts as detailed earlier in this paper, the epipericardial ridge being lined and the arches numbered. The second scheme shows the same conditions when the clavicular rudiment (Cl.) is first present and the sternomastoid is distinct. The result of the lengthening of the neck is given in the third figure. The infrahyoid muscles, fixed to the clavicle and hyoid, are drawn out on the ventral side, the sternomastoid is a fixed structure behind, and the line of flexure marks off the second and first arches in front, so that the third arch area practically corresponds with the skin covering the carotid triangle. I feel no doubt that this is quite correct in a general way, but one cannot affirm that the boundaries of the arch area and the triangle would necessarily correspond in every way. In this connection it is interesting to recall Head's "superior laryngeal" area of hyperaesthesia: it is shown in fig.8, modified from Head's original diagram, and represents a cutaneous area which might very well correspond with the skin surface of the third arch, extended under the conditions just described. It would not be justifiable, of course, to do more than suggest here such a possibility, but it may be said that Head originally proposed (Brain, Vol.xvii,1894) on theoretical grounds an association of the area with the third postoral arch.

It can be seen that there is no support in embryonic human development for the idea that the sinus is covered in by some modification of an operculum derived,as in those lower forms which possess it, from the hyoidarch. it is evident that this arch enlarges considerably and, as a result, hangs over and thus partly hides the sunken area of the sinus, but this is only a superficial appearance and one of short duration. The second groove, deep and clear, persists throughout as the transverse line of flexure, so that the area behind it remains open, and the enlargement of the second arch is apparently only connected with the primary architecture of the outer ear. The only sign of fusion of the second arch with structures behind it is the doubtful. (and inany case very small) closure at its upper part in the 8mm. stage,not affecting the true sinus area in any way, and no indication of any formation resembling an opercular growth-unless it is the pinna-is apparent. The placodal areas which lie at the bottom of the cervical vesicles seem to be closed in by the activity of the paraxial mesoderm, and that belonging to the pharyngeal arches appears to be, in this connection, quite passive.

Finally, a few words may be said about the muscle cells in the epipericardial ridge. The upper cells in this ridge, those continuous with the deeper parts of the down growths from the occipital myotomes, apparently disappear during the evolutions described in this paper. They seem to do so from behind forward,and this is associated with the appearance of the lingual musculature. This is suggestive, but is not enough in itself to allow one to say that there is an actual migration of cells from the occipital region to the tongue. Nevertheless, the direct association of the intrinsic tongue musculature with the occipital myotomes is evident,even if we cannot certainly affirm that migration takes place from this region during ontogeny.

Vestigial remnants in the neck

The conditions not uncommonly met with on the side of the neck and frequently termed "bronchial rests" are evidently abnormal, and hence postulate some abnormality in developmental processes as underlying their presence. Since the account in this paper of the processes which go on in the sinus area would destroy the conception of a closed sinus, which is accepted as a centre round which the formations radiate, so to speak, it may be permissible to indicate what would seem to be possible sources of the fistulae or cysts that come under this heading. The abnormal processes may be divided into (1) abnormal persistence of normal states, or delayed development, and (2) abnormal processes of development.

- The normal formation of ectodermal cavities in association with the sinus region as dealt with in this paper include only the placodal cysts and their ducts: any one or more of these might conceivably persist, either alone or in combination. To these must be addedthe possibility of persistence of one or more of the ectodermal "external pharyngeal ducts" which are connected with the entodermal pouches: these have not been mentioned in this paper because they are not concerned with the changes in surface appearance of the sinus area,but they are,as is well known,deep prolongations of grooves, and they normally disappear before the final stages of the surface changes are entered upon. Outside the sinus field the first groove closes by epithelial fusion, which might remain as a septum.

- Abnormal fusion between the sides of the second groove in some part of its extent would be among the least of possibilities coming under this heading, and one can imagine similar or parallel formations elsewhere: the list could then be extended to conditions of gross abnormality or monstrosity. As in the rest of the body, we are practically quite ignorant of the forces acting behind the surface manifestations, so that it is impossible to imagine along what lines the structures would develop if some small interference with their play were experienced at a very early stage in the evolution of a part: hence one cannot do more than enter these possibilities on the list in the most general terms. it is possible that those cases in which sinuses are found low down in the neck, for instance between the heads of the sternomastoid,may come in this class,although it is not impossible that they may come in (1).

It can be seen,then,that,without calling on a precervical sinus, a very fair list of possible sources of trouble can be made out-but which of the number may really be factors in clinical cases, and which may be nothing more than theoretical figments, I cannot for a moment presume to say.

We come now to a matter more important from an anatomical standpoint, one that bears directly on the position of some of these remnants and affects profoundly the theoretical conception of the third is position,and yet is not taken into account as a rule when these quasi-pathological structures are considered by the clinical pathologist. I refer to the hypoglossal nerve and its course. The nerve lies at first behind the region of arches and grooves, and turns forward along the top of the pericardium: in other words, it lies in the caudal border of the sinus and in the epipericardial ridge. In attaining its ultimate position its loop is drawn up to a higher level and must (being a deep nerve of the body wall) in its transit pass deep to structures connected with the ectoderm, and superficial to all those structures connected with the pharynx. Thus we find it at different stages lying external to pharyngeal pouches and their derivatives, to the carotid vascular system, the hyoid, and the nerves associated with the visceral tube. it is obvious,then,that if any such thing as a connection between the surface and the pharyngeal wall or its derivatives were to persist, the connecting strand would be caught up over the hypoglossal nerve: the same applies, of course, to any connection between the surface and a placodal cyst, which would presumably be in association with its nerve ganglion. Thus every vestigial remnant in the neck that has a deep connection as well as an outer opening would have to pass upward to cross the hypoglossal before it could run to its original deep attachment, and, if such remnants occurred, the existence of deep connecting stalks would seem to be considerably endangered by the transit of the nerve loop. A little consideration of these facts, and remembrance of the changes in position of the nerve, would no doubt lead to more cautious appraisement of the developmental value of vestigial structures when they are encountered.

Summary

- The appearance and nature of the precervical sinus and its boundaries are described and figured.

- It is shown that the sinus does not close in the sense usually understood. The fourth arch is covered, but the third arch remains on the surface of the neck,its are a possibly corresponding with Head's superior laryngeal area.

- Placodal areas associated with IXth and Xth ganglia are covered in and form cervical vesicles, opening at first on the surface but not into a common sinus: they close and disappear very soon, and it is in the covering in of the Xth placode that the fourth arch is involved.

- Infrahyoid and tongue muscles and occipital myotomes are shortly dealt with in so far as they have to do with the formation of the area of the sinus and of the neck.

- Some possible sources of formation of so-called bronchial remnants in the neck are suggested, but no attempt is made to give any proportionate value to the suggestions.

- Attention is called to the necessity of recognising the position, and changes of position in transit, of the hypoglossal nerve when dealing with any such remnants in the neck.

Description Of Plate I

Fig. 1. Head of embryo of 4-9 mm., seen from the left. P. pericardium; C. 1, first cervical myotome; Ot.,otocyst.

Fig. 3. The precervical sinus in an embryo of 8 mm. seen from the left side. For description see text.

Fig. 4. Region of precervical sinus in 10mm. embryo. Left side. P, pericardium; I, II, III, pharyngeal arches. The widely open placodal recess of vagus, pl.a.X, is below and behind the narrow duct, pl.d.IX, leading to the glossopharyngeal ganglion. The epipericardial ridge is very prominent below and behind the third arch

|

|

Animation based on Fig. 7. |

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Paper - The Disappearance of the Precervical Sinus. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Paper_-_The_Disappearance_of_the_Precervical_Sinus

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G