Abnormal Development - Twinning

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Introduction

While singleton human births are the most common, there are also several different forms of twinning (multiple pregnancy) that may arise in the early weeks (first two weeks) of development. The two major twinning forms are dizygotic (from two eggs fertilised by two different spermatazoa) and monozygotic (from one fertilised egg and a single spermatazoa). Higher multiple pregnancies (triplets, quadruplets, etc.) are generally dizygotic with ultrasound acting as the earliest diagnostic test for all multiple pregnancies.

Dizogotic twinning can be described following the normal developmental sequence, while monozygotic twinning requires a perturbation of developmental event(s) to occur in the first weeks following fertilisation. The later stages of monozygotic embryonic development may well follow the normal pattern of differentiation, though growth during the fetal period can be lower.

Twinning rate differences over time and between countries are thought due to variation in dizygotic twinning.[1] Monozygotic twinning is thought to occur at a relatively constant rate of 3.5–4 per 1000 births across human populations, with assisted reproductive technologies possibly contributing to recent changes.[2][3]

In addition to the zygosity, the additional twinning classifying terms refer to the type of placenta and fetal membranes, either separate or shared by the twins. Twinning has both a higher incidence of mortality in twins, due mainly to preterm delivery, and of incidence of birth defects. Single fetal mortality also occurs in 3.7 - 6.8% of all twin pregnancies, and there are more maternal risks involved with multiple pregnancies. As a positive, twins do appear to have a lower incidence of trisomy 21.[4]

| Historic Embryology - Twinning |

|---|

| 1915 Twin embryos 17-19 somites | 1916 Conjoined Twins | 1922 Monozygotic origin identical twins | 1927 Separate amnions | 1942 Twin chorion | 1955 Twins and multiple birth |

| Carnegie Embryos: 8505a 8505b 7170a 7545 9009a and b 9123 5542B 5935A 5621A |

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers | |

|---|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Twinning | Monozygotic Twinning |

Twin-twin Transfusion Syndrome |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

Dizygotic Twinning

Dizygotic twins (DZ, fraternal, non-identical) arise from separate fertilization events involving two separate oocyte (egg, ova) and spermatozoa (sperm). These twins may also implant at different sites within the uterus. Maternal factors such as genetic history, advanced age, increased parity, elevated FSH concentrations, maternal height (taller) and maternal body mass index (30>) increase the risk of dizygotic twins.[14] There are also theories that suggest that non-in vitro fertilization dizygotic twins may have more in common with monozygotic mechanisms and not be due to purely twin ovulatory events.[15]

Monoygotic Twinning

Monoygotic twins (MZ, identical) produced from a single fertilization event (one fertilised egg and a single spermatozoa, form a single zygote), these twins therefore share the same genetic makeup. Occurs in approximately 3-5 per 1000 pregnancies, more commonly with aged mothers. The later the twinning event, the less common are initially separate placental membranes and finally resulting in conjoined twins.

| Week | Week 1 (GA week 3) | Week 2 (GA week 4) | |||||||||||||

| Day | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Cell Number | 1 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 32 | 128 | bilaminar | ||||||||

| Event | Ovulation | Fertilization | First cell division | Morula | Early blastocyst | Late blastocyst

Hatching |

Implantation starts | X inactivation | |||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Monoygotic

Twin Type |

Diamniotic

Dichorionic |

Diamniotic

Monochorionic |

Monoamniotic

Monochorionic |

Conjoined | |||||||||||

Table based upon recent a recent twinning review.[16] Links: twinning

Sesquizygotic Twinning

Sesquizygotic twinning is a rare intermediate form of twinning, between mono-zygotic and dizygotic twinning, the twins can be maternally identical but chimerical for their paternal genome. Such a rare twinning event has been recently identified and published.[6]

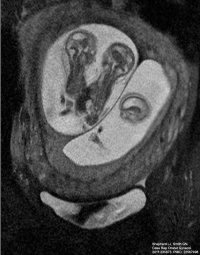

Conjoined Twinning

- Diprosopus - two faces are located on the same side of a single head. A form of parapagus (less than 1% of conjoined twins).

- Parapagus - side-by-side connection with a shared pelvis and variable cephalic sharing (28 % of conjoined twins).

- Ischiopagus - conjoined pelvis (6 –11 % of conjoined twins).

- Heteropagus - asymmetrical form of twinning when one of the twins monopolizes the placental blood at the expense of other fetus.[17]

Both ischiopagus and pygopagus conjoined twins have a range of variable spinal abnormalities.[18]

|

|

|

| Conjoined twins ultrasound[19] | Conjoined twins MRI[19] | Conjoined twins after birth[20] |

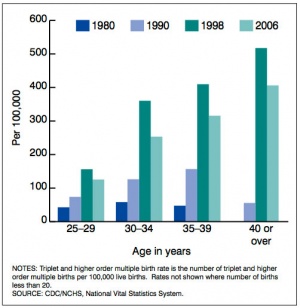

Triplets

Triplet birth incidence is rare (1 / 10,000 births) though this number increased (6 / 10,000 births) during the early stages of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and has since dropped again with single embryo transfer (SET) policies. Triplets are often born premature and with a low birth weight. A recent large study in the Netherlands has characterised birth weight, zygosity and environmental effects[10]

- "There was no effect of assisted reproductive techniques on triplet birth weight. At gestational age 24 to 40 weeks triplets gained on average 130 grams per week; boys weighed 110 grams more than girls and triplets of smoking mothers weighted 104 grams less than children of non-smoking mothers. Monozygotic triplets had lower birth weights than di- and trizygotic triplets and birth weight discordance was smaller in monozygotic triplets than in dizygotic and trizygotic triplets. The correlation in birth weight among monozygotic and dizygotic triplets was 0.42 and 0.32, respectively. In nearly two-thirds of families, the heaviest and the lightest triplet had a birth weight discordance over 15%."

Twinning Prevalence

USA Data 2012

A recent study of twinning in developed countries[21]

- Twins constitute 2% - 4% of all births

- Rate of twining has increased by 76% between 1980 and 2009.

- Rate of preterm birth (<37 weeks) among twins is about 60%.

- Of all twin preterm births in the United States

- roughly half are indicated

- a third are due to spontaneous onset of labor

- about 10% are due to preterm premature rupture of membranes.

- recent decline in neonatal morbidity (one or more of 5-minute Apgar score <4, neonatal seizures or assisted ventilation for ≥ 30 minutes) among twin gestations.

- ART twins are more likely to deliver at <37 weeks.

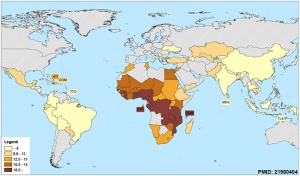

World Data 2003

The prevalence of spontaneous livebirth monozygotic twinning is relatively constant, with variability in dizygotic twinning around the world.[16]

- Asia 6 in 1000

- Europe/USA 10-20 in 1000

- African-Americans 26 in 1000

- Africa 40 in 1000

- Japan 1 in 250

- Nigeria 1 in 11

Monozygotic conjoined twins - 1 in 100,000 births (more female)

United States of America - 2.7% of all confinements resulted in a multiple birth in 1996 (U.S. Census Bureau, 1999, p.80)

New Zealand - 1.6% in 1998 (Statistics New Zealand, 2000, p.70)

Australia - 1.5% in 1998 (ABS, see below)

Australian Data 2002

Data from the Year Book Australia (2002) looking at pregnancies (confinements) shows the number resulting in a singleton live birth has been declining while the number resulting in multiple births has been increasing. This has been attributed to increased number of births to older women and the increasing use of assisted conception technologies.

"While the number of confinements resulting in multiple births remains relatively low, there has been a steady increase since the 1970s."

Multiple Births

- 1980 - 1.0% (2,249 of 223,318; 2,219 twins, 30 triplets or higher)

- 1990 - 1.2% (3,168 of 259,435; 3,074 twins, 94 triplets or higher)

- 2000 - 1.6% (3,900 of 245,700; 3,800 twins, 100 triplets or higher)

"Among older women this trend is more pronounced. In 1980, there were 730 confinements resulting in multiple births to women aged 30 years and over, constituting 1% of all confinements among women over 30. By 2000, this number had increased to 2,300 (2%)." [22]

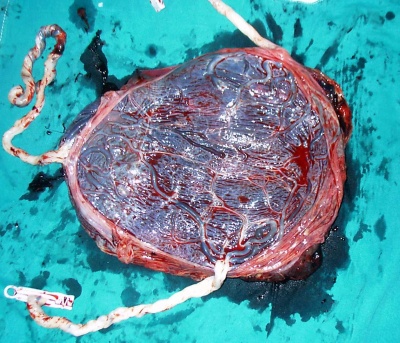

Placenta

|

|

| Monochorionic Twin Placenta[23]

Legend

|

Monochorionic Triamniotic Triplet Placenta[24]

|

- Links: Placenta Development

| Placental Membranes | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Dichorionic diamniotic

GA 13 week = 11 week |

Monochorionic diamniotic

GA 12 week = 10 week |

| Thick dividing membrane and "lambda" or twin peak sign at the junction with the placenta. | Thin dividing membrane and "T" sign at the junction with the placenta. |

- Links: placental membranes | ultrasound

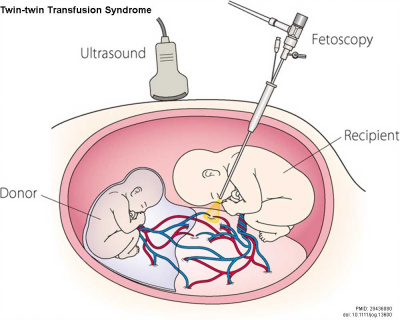

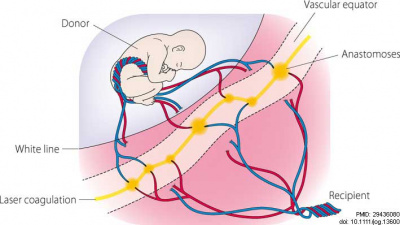

Twin-twin Transfusion Syndrome

The abnormality of twin–twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) can occur in both monochorionic and diamniotic twins that results from an unbalanced blood flow from one to the other in utero. Monozygotic twin pregnancies carry a 10-20% risk of twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Diagnosis of TTTS is generally by ultrasound: single placenta, same fetal sex, a “T-sign” and the amniotic fluid volume on either side of the dividing fetal membranes.

- Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, vein of galen malformation, and transposition of the great arteries in a pair of monochorionic twins: coincidence or related association? [25] "The development of TTTS, VGM, and TGA in a single monochorionic pregnancy could be pure coincidence, but there might also be a causative link. We discuss the possible contribution of genetic factors, fetal flow fluctuations, vascular endothelial growth factors, and the process of twinning itself to the development of these congenital anomalies."

Fetoscopic Laser Therapy

Fetoscopic Laser Therapy also called fetoscopic selective laser photocoagulation (SLPC) has been used as a treatment for advanced stages of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome.[26][27]

| Fetoscopic laser photocoagulation [28] | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Fetoscopic laser photocoagulation | Anastomoses ablation sites |

Quintero Staging System

Quintero and others in 1999 established a sonographic and clinical parameter staging system (Quintero staging system) for TTTS.[29]

- Stage I - The fetal bladder of the donor twin remains visible sonographically.

- Stage II = The bladder of the donor twin is collapsed and not visible by ultrasound.

- Stage III - Critically abnormal fetal Doppler studies noted. This may include absent or reversed end-diastolic velocity in the umbilical artery, absent or reverse flow in the ductus venosus, or pulsatile flow in the umbilical vein.

- Stage IV - Fetal hydrops present.

- Stage V - Demise of either twin.

This Quintero staging system efficacy has been recently suggested as not providing accurate information about prognosis.[30][31] An alternative Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) cardiovascular score, appears to also be "not of clinical use as a prognostic marker in TTTS".[32]

Acardiac Twins

Historically called chorioangiopagus parasiticus. Acardia, also called twin reversed-arterial perfusion (TRAP) sequence, is an extreme form of twin-twin transfusion syndrome. In a twinned human fetal development where monozygotic twinning or higher multiple births have an artery-to-artery and a vein-to-vein anastomosis in the monochorial placenta.[33]

The incidence of this condition is 1% of monochorionic twin pregnancies (approx. 1 of 35,000 pregnancies).

Premature Ovarian Failure

Both forms of twinning have been shown to be at higher risk of Premature Ovarian Failure (POF).[34] The same study also showed that the menopausal ages were more concordant than for dizogotic twin-pairs, confirming that the timing of menopause has a heritable component.

Trisomy 21

A recent 2014 study[4] of European data for the period 1990-2009 (14.8 million births 2.89% multiple births) showed the risk of trisomy 21 (Down Syndrome) per fetus/baby is lower in multiple than singleton pregnancies. The authors suggest that these estimates can be used for genetic counselling and prenatal screening.

- Links: Trisomy 21

Additional Images

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Smits J & Monden C. (2011). Twinning across the Developing World. PLoS ONE , 6, e25239. PMID: 21980404 DOI.

- ↑ Gee RE, Dickey RP, Xiong X, Clark LS & Pridjian G. (2014). Impact of monozygotic twinning on multiple births resulting from in vitro fertilization in the United States, 2006-2010. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 210, 468.e1-6. PMID: 24373946 DOI.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kanter JR, Boulet SL, Kawwass JF, Jamieson DJ & Kissin DM. (2015). Trends and correlates of monozygotic twinning after single embryo transfer. Obstet Gynecol , 125, 111-7. PMID: 25560112 DOI.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Boyle B, Morris JK, McConkey R, Garne E, Loane M, Addor MC, Gatt M, Haeusler M, Latos-Bielenska A, Lelong N, McDonnell R, Mullaney C, O'Mahony M & Dolk H. (2014). Prevalence and risk of Down syndrome in monozygotic and dizygotic multiple pregnancies in Europe: implications for prenatal screening. BJOG , 121, 809-19; discussion 820. PMID: 24495335 DOI.

- ↑ Casati D, Pellegrino M, Cortinovis I, Spada E, Lanna M, Faiola S, Cetin I & Rustico MA. (2019). Longitudinal Doppler references for monochorionic twins and comparison with singletons. PLoS ONE , 14, e0226090. PMID: 31809530 DOI.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gabbett MT. etal., Molecular Support for Heterogonesis Resulting in Sesquizygotic Twinning. (2019) New England Journal of Medicine, 380(9), 842–849. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1701313

- ↑ Melo Â, Dinis R, Portugal A, Sousa AI & Cerveira I. (2018). Early prenatal diagnosis of parapagus conjoined twins. Clin Pract , 8, 1039. PMID: 29657701 DOI.

- ↑ Tisler M, Thumberger T, Schneider I, Schweickert A & Blum M. (2017). Leftward Flow Determines Laterality in Conjoined Twins. Curr. Biol. , 27, 543-548. PMID: 28190730 DOI.

- ↑ Gupta S, Fox NS, Feinberg J, Klauser CK & Rebarber A. (2015). Outcomes in twin pregnancies reduced to singleton pregnancies compared with ongoing twin pregnancies. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 213, 580.e1-5. PMID: 26071922 DOI.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lamb DJ, Middeldorp CM, van Beijsterveldt CE, Vink JM, Haak MC & Boomsma DI. (2011). Birth weight in a large series of triplets. BMC Pediatr , 11, 24. PMID: 21453554 DOI.

- ↑ Weghofer A, Klein K, Stammler-Safar M, Worda C, Barad DH, Husslein P & Gleicher N. (2010). The impact of fetal gender on prematurity in dichorionic twin gestations after in vitro fertilization. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. , 8, 57. PMID: 20534177 DOI.

- ↑ Hardin J, Carmichael SL, Selvin S, Lammer EJ & Shaw GM. (2009). Increased prevalence of cardiovascular defects among 56,709 California twin pairs. Am. J. Med. Genet. A , 149A, 877-86. PMID: 19353581 DOI.

- ↑ Yusuf K & Kliman HJ. (2008). The fetus, not the mother, elicits maternal immunologic rejection: lessons from discordant dizygotic twin placentas. J Perinat Med , 36, 291-6. PMID: 18598117 DOI.

- ↑ Hoekstra C, Zhao ZZ, Lambalk CB, Willemsen G, Martin NG, Boomsma DI & Montgomery GW. (2008). Dizygotic twinning. Hum. Reprod. Update , 14, 37-47. PMID: 18024802 DOI.

- ↑ Boklage CE. (2009). Traces of embryogenesis are the same in monozygotic and dizygotic twins: not compatible with double ovulation. Hum. Reprod. , 24, 1255-66. PMID: 19252194 DOI.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Hall JG. (2003). Twinning. Lancet , 362, 735-43. PMID: 12957099 DOI.

- ↑ Sharma G, Mobin SS, Lypka M & Urata M. (2010). Heteropagus (parasitic) twins: a review. J. Pediatr. Surg. , 45, 2454-63. PMID: 21129567 DOI.

- ↑ Fieggen AG, Dunn RN, Pitcher RD, Millar AJ, Rode H & Peter JC. (2004). Ischiopagus and pygopagus conjoined twins: neurosurgical considerations. Childs Nerv Syst , 20, 640-51. PMID: 15278384 DOI.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Shepherd LJ & Smith GN. (2011). Conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol , 2011, 235873. PMID: 22567498 DOI.

- ↑ Batool T & Akhtar J. (2010). Conjoined twins: the flip side. APSP J Case Rep , 1, 23. PMID: 22953266

- ↑ Ananth CV & Chauhan SP. (2012). Epidemiology of twinning in developed countries. Semin. Perinatol. , 36, 156-61. PMID: 22713495 DOI.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics Year Book Australia 2002

- ↑ de Haseth SB, Haak MC, Roest AA, Rijlaarsdam ME, Oepkes D & Lopriore E. (2012). Right ventricular outflow tract obstruction in monochorionic twins with selective intrauterine growth restriction. Case Rep Pediatr , 2012, 426825. PMID: 23050183 DOI.

- ↑ Gul A, Aslan H, Cebeci A, Ceylan Y & Tekirdag AI. (2005). Monochorionic triamniotic triplet pregnancy with a co-triplet fetus discordant for congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung. Reprod Health , 2, 2. PMID: 15819977 DOI.

- ↑ Steggerda S, Lopriore E, Sueters M, Bartelings M, Vandenbussche F & Walther F. (2006). Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, vein of galen malformation, and transposition of the great arteries in a pair of monochorionic twins: coincidence or related association?. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. , 9, 52-5. PMID: 16808639 DOI.

- ↑ Khalek N, Johnson MP & Bebbington MW. (2013). Fetoscopic laser therapy for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. , 22, 18-23. PMID: 23395141 DOI.

- ↑ Walsh CA & McAuliffe FM. (2012). Recurrent twin-twin transfusion syndrome after selective fetoscopic laser photocoagulation: a systematic review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol , 40, 506-12. PMID: 22378622 DOI.

- ↑ Sago H, Ishii K, Sugibayashi R, Ozawa K, Sumie M & Wada S. (2018). Fetoscopic laser photocoagulation for twin-twin transfusion syndrome. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. , 44, 831-839. PMID: 29436080 DOI.

- ↑ Quintero RA, Morales WJ, Allen MH, Bornick PW, Johnson PK & Kruger M. (1999). Staging of twin-twin transfusion syndrome. J Perinatol , 19, 550-5. PMID: 10645517

- ↑ Ville Y. (2007). Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome: time to forget the Quintero staging system?. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol , 30, 924-7. PMID: 18044824 DOI.

- ↑ Rossi AC & D'Addario V. (2009). The efficacy of Quintero staging system to assess severity of twin-twin transfusion syndrome treated with laser therapy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol , 26, 537-44. PMID: 19283655 DOI.

- ↑ Stirnemann JJ, Nasr B, Proulx F, Essaoui M & Ville Y. (2010). Evaluation of the CHOP cardiovascular score as a prognostic predictor of outcome in twin-twin transfusion syndrome after laser coagulation of placental vessels in a prospective cohort. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol , 36, 52-7. PMID: 20582931 DOI.

- ↑ Søgaard K, Skibsted L & Brocks V. (1999). Acardiac twins: pathophysiology, diagnosis, outcome and treatment. Six cases and review of the literature. Fetal. Diagn. Ther. , 14, 53-9. PMID: 10072652 DOI.

- ↑ Gosden RG, Treloar SA, Martin NG, Cherkas LF, Spector TD, Faddy MJ & Silber SJ. (2007). Prevalence of premature ovarian failure in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Hum. Reprod. , 22, 610-5. PMID: 17065173 DOI.

Books and Journals

Twin Research and Human Genetics "A quality peer-reviewed journal of the International Society for Twin Studies (ISTS). Founded in Rome in 1974, ISTS is an international, nonpolitical, nonprofit, multidisciplinary scientific organisation. Its purpose is to further research and public education in all fields related to twins and twin studies, for the mutual benefit of twins and their families and of scientific research in general."

Multiple Pregnancy: The Management of Twin and Triplet Pregnancies in the Antenatal Period. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (UK). London: RCOG Press; 2011 Sep. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 129.) Bookshelf PMID 22855972

Reviews

Machin G. (2009). Non-identical monozygotic twins, intermediate twin types, zygosity testing, and the non-random nature of monozygotic twinning: a review. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet , 151C, 110-27. PMID: 19363805 DOI.

Aston KI, Peterson CM & Carrell DT. (2008). Monozygotic twinning associated with assisted reproductive technologies: a review. Reproduction , 136, 377-86. PMID: 18577552 DOI.

Muggli EE & Halliday JL. (2007). Folic acid and risk of twinning: a systematic review of the recent literature, July 1994 to July 2006. Med. J. Aust. , 186, 243-8. PMID: 17391087

Prapas N, Kalogiannidis I, Prapas I, Xiromeritis P, Karagiannidis A & Makedos G. (2006). Twin gestation in older women: antepartum, intrapartum complications, and perinatal outcomes. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. , 273, 293-7. PMID: 16283408 DOI.

Smith GC, Shah I, White IR, Pell JP & Dobbie R. (2005). Mode of delivery and the risk of delivery-related perinatal death among twins at term: a retrospective cohort study of 8073 births. BJOG , 112, 1139-44. PMID: 16045531 DOI.

Articles

Liao AW, Brizot Mde L, Kang HJ, Assunção RA & Zugaib M. (2012). Longitudinal reference ranges for fetal ultrasound biometry in twin pregnancies. Clinics (Sao Paulo) , 67, 451-5. PMID: 22666788 DOI.

Vela G, Luna M, Barritt J, Sandler B & Copperman AB. (2011). Monozygotic pregnancies conceived by in vitro fertilization: understanding their prognosis. Fertil. Steril. , 95, 606-10. PMID: 20522324 DOI.

Palmer JS, Zhao ZZ, Hoekstra C, Hayward NK, Webb PM, Whiteman DC, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Duffy DL & Montgomery GW. (2006). Novel variants in growth differentiation factor 9 in mothers of dizygotic twins. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. , 91, 4713-6. PMID: 16954162 DOI.

Search Pubmed

Search Pubmed: Twinning | Monozygotic Twinning | Diygotic Twinning | Twin-twin Transfusion Syndrome

Pubmed Books

- National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (UK). Multiple Pregnancy: The Management of Twin and Triplet Pregnancies in the Antenatal Period. London: RCOG Press; 2011 Sep. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 129.) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83105/ "This guideline contains recommendations specific to twin and triplet pregnancies and covers the following clinical areas: optimal methods to determine gestational age and chorionicity; maternal and fetal screening programmes to identify structural abnormalities, chromosomal abnormalities and feto-fetal transfusion syndrome (FFTS), and to detect intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR); the effectiveness of interventions to prevent spontaneous preterm birth; and routine (elective) antenatal corticosteroid prophylaxis for reducing perinatal morbidity. The guideline also advises how to give accurate, relevant and useful information to women with twin and triplet pregnancies and their families, and how best to support them."

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- International Society for Twin Studies

- Australian Twin Registry

- The Danish Twin Registry "The Danish Twin Registry (DTR) is one of the oldest twin registries in the world. It was established in the 1950's with the aim of studying causes of cancer and it comprises now twins born through more than 130 years."

- Berlin Twin Register

- Norwegian Twin Registry PMID 22947319

- United Kingdom - Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology "The Department of Twin Research and Genetic Epidemiology (DTR) encompasses the biggest UK adult twin registry of 12,000 twins used to study the genetic and environmental aetiology of age related complex traits and diseases."

- USA - National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council (NAS-NRC) Twin Registry "It consists of 15,924 white male twin pairs born in the years 1917 to 1927 (inclusive), both of whom served in the armed forces, mostly during World War II."

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Abnormal Development - Twinning. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Twinning

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G