Estrous Cycle

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Introduction

The estrous cycle (British spelling, oestrous) is the main reproductive cycle of other species females of non-primate vertebrates, for example rats, mice, horses, pig have this form of reproductive cycle. Also do not confuse with "estrus", which is a phase of the cycle.

There are also a variety of different forms:

- Polyestrous Animals - Estrous cycles throughout the year (cattle, pigs, mice, rats).

- Seasonally Polyestrous Animals - Animals that have multiple estrous cycles only during certain periods of the year (horses, sheep, goats, deer, cats).

- Monestrous Animals - Animals that have one estrous cycle per year (dogs, wolves, foxes, and bear)

| Links: estrous cycle | mouse estrous cycle | ovary | oocyte | uterus | menstrual cycle |

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Estrous Cycle |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

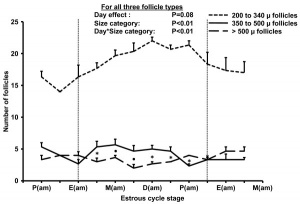

Estrous Cycle Stages

The descriptions below refer to the "typical" mammalian cycle.

- proestrus - estrus - metestrus - diestrus

Proestrus

The first stage in the estrous cycle immediately before estrus characterized by development of both the endometrium and ovarian follicles.

Estrus

The second stage in the estrous cycle immediately before metestrus characterized by a receptivity to a male and to mating, often referred to as "heat" or "in heat". Pheromones may also be secreted only at this stage of her cycle.

Metestrus

The third stage in the estrous cycle immediately before diestrus characterized by sexual inactivity and the formation of the corpus luteum.

Diestrus

The last stage in the estrous cycle immediately before the next cycle proestrus characterized by a functional corpus luteum and an increase in the blood concentration of progesterone.

Anestrus

Not a stage in the estrous cycle, but a prolonged period of sexual rest where the reproductive system is quiescent.

Vaginal Smear Comparison

| Vaginal Smear Comparison Table | |

|---|---|

| Guinea pig | Rat (Long and Evans) |

| I. Superficial squamous cells with pyknotic nuclei; progressive leucopenia. | 1. Small round nucleated cells; disappearance of leucocytes. |

Intermediate (cornification) period

|

Cornification period

|

| II, III, IV. Appearance of deep layer cells; reappearance and great exodus of leucocytes; gradual disappearance of cornifiecl cells; sometimes erythrocytes present. | 4. Leucocytic-cornified cell stage; reappearance of leucocytes; gradual disappearance of the cornified cells. |

| V. Dioestrus: Leucocytes and atypical atypical vaginal cells. | 5. Dioestrus: Leucocytes and vaginal cclls. |

| |

Rat Estrous Cycle

One of the best characterised polyestrous reproductive cycles, though different species of rats may differ in reproduction. In general, puberty occurs at 6-8 weeks when the estrous cycle commences each cycle is 4-5 days. The estrous cycle is polyestrous, more than one estrous cycle during a specific yearly time, with an estrous period of approximately 12 hours.

See the review of the rat estrous cycle.[5]

- Links: rat | PubMed - rat estrous cycle

Mouse Estrous Cycle

The mouse oestrus cycle is 4-6 days, with oestrus lasting less than 1 day. The estrous cycle stops during lactation except for one oestrus 12-20 hours postpartum. The information below refers to determining the stage of the estrous cycle in the mouse by the appearance of the vagina.[6]

- Estrous Diestrus - Vagina has a small opening and the tissues are bluish-purple in color and very moist.

- Proestrus - Vagina is gaping and the tissues are reddish-pink and moist. Numerous longitudinal folds or striations are visible on both the dorsal and ventral lips.

- Estrus - Vaginal signs are similar to proestrus, but the tissues are lighter pink and less moist, and the striations are more pronounced.

- Metestrus-1 - Vaginal tissues are pale and dry. Dorsal lip is not as edematous as in estrus.

- Metestrus-2 - Vaginal signs are similar to metestrus-1, but the lip is less edematous and has receded. Whitish cellular debris may line the inner walls or partially fill the Vagina.

- Links: mouse estrous cycle

Pig Estrous Cycle

The feedback systems between the ovaries, uterus, hypothalamus and pituitary gland govern a cycle of events that takes 18-21 days. If conception occurs this cyclic pattern is interrupted and pregnancy is maintained for approximately 114 days. Removal of the sucking stimulus at weaning triggers a new sequence of events.

- Links: pig | PubMed- pig estrous cycle

Dog Estrous Cycle

- Proestrus (9 days) - Precedes estrus, estradiol concentration increases as ovarian follicules mature and the uterus enlarges. The vaginal epithelium proliferates accompanied by diapedesis of erythrocytes (most cells in vaginal smear) from uterine capillaries.

- Estrus (9 days) - Accompanied by female mating behaviour, glandular secretions increase, the vaginal epithelium becomes hyperemic, and ovulation occurs. Cycle is influenced mainly by estrogens and the interval between successive estrus cycles is about 7 months.

- Diestrus (70-80 days) - Accompanied by female non-mating behaviour, corpus lutea present and secretes progesterone. Uterine glands undergo hypertrophy and hyperplasia, vaginal secretions and the cervix constricts.

- Anestrus - Anestrus is a prolonged period of sexual rest where the reproductive system is quiescent.

- Links: dog

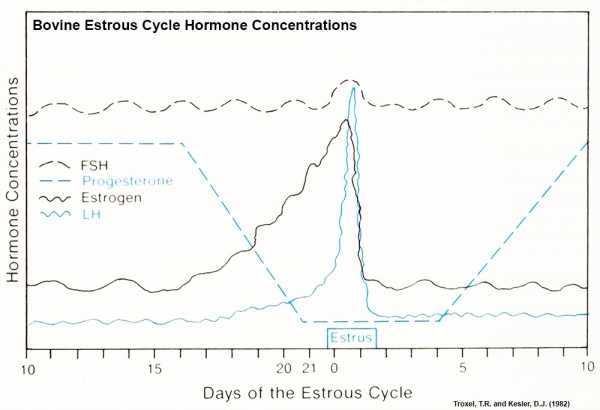

Bovine Estrous Cycle

Specific hormone concentrations are not shown in the above graph, only the relative hormone levels at different times during the cycle.

- Links: cow

Historic

1937 - Etymology and pronunciation of the word "oestrus" and its derivatives[7]

This word seems to offer more difficulties as to pronunciation and spelling than any other technical word in biology. Derived originally from the Greek oloxpos, signifying the gadfly, and taken over into Latin as oestrus, the word came secondarily to mean frenzy or strong desire. The Latin derivative is properly of masculine gender, following the Greek, but we are told by Tyson[8] that some grammarians gave it the neuter form oestrum as early as 400 a.v. In its more general senses the word became naturalized in English with the spelling oestrum and has been so used in prose and poetic literature by many writers (see Tyson’s article and the Oxford English Dictionary).

In the original Greek and Latin the meaning of the word already included, among other forms of excitement, the recurrent sexual impulse of animals. We owe its present definite technical use, however, to the late Walter Heape,[9] whose analysis and terminology of the phenomena of the reproductive cycle form the basis of research on that subject in the present century. As pointed out by Asdell,[10] Heape was not using the well-naturalized English word oestrum, which in English signifies any form of recurrent excitement (e.g., the poetic frenzy), but was deliberately adopting the Latin word oestrus for use as a specific technical term meaning in English “periodic sexual excitement of the female.” Writers having the latter significance in mind should, for the sake of precision, respect the difference and use the word oestrus.

It is scarcely necessary to point out that the nominative form is oestrus, and the adjectival form oestrous (cf. fungus, fungous; mucus, mucous).

As to pronunciation, the Greek and Latin diphthong of the first syllable has become in English merely a digraph, and in England is pronounced like long e, as in thief. Wyld’s Dictionary of “Received Standard English” gives this pronunciation only, The Oxford English Dictionary gives also the short e, as in yet, as an alternative pronunciation, but by the time the Shorter Oxford Dictionary reached the letter O, the compilers had discovered that the short e is an American usage. The word oestrum seems to have first appeared in the American dictionaries in the 1860 edition of Worcester and the 1864 Webster. In both eases the short pronunciation of e was alone given. Webster continued to give preference to this pronunciation, but since the 1909 revision cites also the long e as a non-preferred pronunciation. The Century Dictionary of 1911 gives the long e only, but on the other hand the 1913 Funk and Wagnalls gives the short e only.

It is evident, therefore, that the pronunciation of the non-technical word oestrum, and consequently of the technical term oestrus, oestrin, oestrogenic, ete., is ... (truncated)

References

- ↑ Liman N & Ateş N. (2020). Abundances and localizations of Claudin-1 and Claudin-5 in the domestic cat (Felis catus) ovary during the estrous cycle. Anim. Reprod. Sci. , 212, 106247. PMID: 31864490 DOI.

- ↑ Kutzler MA. (2018). Estrous Cycle Manipulation in Dogs. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. , 48, 581-594. PMID: 29709316 DOI.

- ↑ Cora MC, Kooistra L & Travlos G. (2015). Vaginal Cytology of the Laboratory Rat and Mouse: Review and Criteria for the Staging of the Estrous Cycle Using Stained Vaginal Smears. Toxicol Pathol , 43, 776-93. PMID: 25739587 DOI.

- ↑ Singh P, Krishna A & Sridaran R. (2011). Changes in bradykinin and bradykinin B(2)-receptor during estrous cycle of mouse. Acta Histochem. , 113, 436-41. PMID: 20546864 DOI.

- ↑ Hubscher CH, Brooks DL & Johnson JR. (2005). A quantitative method for assessing stages of the rat estrous cycle. Biotech Histochem , 80, 79-87. PMID: 16195173 DOI.

- ↑ Champlin AK, Dorr DL & Gates AH. (1973). Determining the stage of the estrous cycle in the mouse by the appearance of the vagina. Biol. Reprod. , 8, 491-4. PMID: 4736343

- ↑ Corner GW. Etymology and pronunciation of the word "oestrus" and its derivatives. (1937) Science. 85(2199):197-198. PMID 17844622

- ↑ Stuart L. Tyson, Sctexce, 612: 74, 1931.

- ↑ Walter Heape, Quart. Jour, Micros, Soi,, ns, 44: 1, 1901,

- ↑ Sidney A, Asdell, Screncr, 75: 131, 1932.

Reviews

Westwood FR. (2008). The female rat reproductive cycle: a practical histological guide to staging. Toxicol Pathol , 36, 375-84. PMID: 18441260 DOI.

Goldman JM, Murr AS & Cooper RL. (2007). The rodent estrous cycle: characterization of vaginal cytology and its utility in toxicological studies. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. , 80, 84-97. PMID: 17342777 DOI.

Articles

Caligioni CS. (2009). Assessing reproductive status/stages in mice. Curr Protoc Neurosci , Appendix 4, Appendix 4I. PMID: 19575469 DOI.

Hubscher CH, Brooks DL & Johnson JR. (2005). A quantitative method for assessing stages of the rat estrous cycle. Biotech Histochem , 80, 79-87. PMID: 16195173 DOI.

Su P, Wu JC, Sommer JR, Gore AJ, Petters RM & Miller WL. (2005). Conditional induction of ovulation in mice. Biol. Reprod. , 73, 681-7. PMID: 15917351 DOI.

Marcondes FK, Bianchi FJ & Tanno AP. (2002). Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations. Braz J Biol , 62, 609-14. PMID: 12659010

Champlin AK, Dorr DL & Gates AH. (1973). Determining the stage of the estrous cycle in the mouse by the appearance of the vagina. Biol. Reprod. , 8, 491-4. PMID: 4736343

Search Pubmed

Search Pubmed Now: Estrous Cycle | Oestrous Cycle

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

| Animal Development: axolotl | bat | cat | chicken | cow | dog | dolphin | echidna | fly | frog | goat | grasshopper | guinea pig | hamster | horse | kangaroo | koala | lizard | medaka | mouse | opossum | pig | platypus | rabbit | rat | salamander | sea squirt | sea urchin | sheep | worm | zebrafish | life cycles | development timetable | development models | K12 |

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Estrous Cycle. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Estrous_Cycle

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G