Postnatal - Vaccination

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| Educational Use Only - Embryology is an educational resource for learning concepts in embryological development, no clinical information is provided and content should not be used for any other purpose. |

Introduction

Although the use of most vaccines during pregnancy is not usually recommended on precautionary grounds, there is no convincing evidence that pregnancy should be an absolute contraindication to the use of any vaccine, particularly inactivated vaccines. The only exception is vaccinia virus (smallpox vaccination), which has been shown to cause fetal malformation. For Australian information see the Australian Immunisation Handbook (June2015)[1]

- AIH 10th edition 3.3.2 - Women planning pregnancy "The need for vaccination, particularly for hepatitis B, measles, mumps, rubella and varicella, should be assessed as part of any pre-conception health check. Where previous vaccination history or infection is uncertain, relevant serological testing can be undertaken to ascertain immunity to hepatitis B, measles, mumps and rubella."

WHO - "In 2018, an estimated 19.4 million infants worldwide were not reached with routine immunization."

Tinycc Vaccination page - http://tiny.cc/Vaccination

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Neonatal Vaccination | Postnatal Vaccination | Maternal Vaccination | Vaccination |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

Neonatal Vaccination

Vaccination of premature infants

A recent study has looked at Wheezing lower respiratory disease hazard ratios (HR) for vaccination of premature infants.[10] Premature infants are at increased risk of wheezing in association with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus infections. The study found no evidence of increased WLRD risk following routine vaccinations of premature infants. WLRD risk among non-fragile premature infants appears to be reduced for a few weeks after live attenuated vaccinations.

- "Wheezing lower respiratory disease hazard ratios (HR) were not significantly elevated for any vaccine type among non-fragile or fragile premature infants. Among non-fragile infants the 8-14 days HR was significantly reduced for live attenuated MMR (0.68, 0.52-0.88) and Varicella (0.71, 0.53-0.94) vaccines, and similarly but insignificantly reduced for infrequently used live attenuated OPV vaccine (0.70, 0.46-1.06). There was a smaller significant reduction (0.83, 0.69-0.998) in the 15-30 days HR for MMR and a similar but not significant reduction (0.86, 0.71-1.05) in the 31-44 days HR for MMR. Hepatitis B vaccine (HBV), which is not a live vaccine, had significantly reduced 8-14 days (0.84, 0.72-0.98) and 31-44 days (0.88, 0.78-0.98) HRs among non-fragile infants. The apparent protective effect of HBV may be confounded by live vaccines administered simultaneously with the third dose of HBV. Among fragile infants there was a large significant reduction in the 8-14 days HR for live attenuated OPV vaccine (0.40, 0.23-0.70) and smaller significant reductions in the 8-14 days HR for inactivated DTaP (0.82, 0.71-0.95), Hib (0.83, 0.73-0.96), and PCV7 (0.84, 0.70-0.997) vaccines. Delays in vaccinating fragile infants may have made simultaneous administration of live vaccines and third doses of these inactivated vaccines more likely."

Australian Immunisation Handbook

The purpose of The Australian Immunisation Handbook[1] is to provide clinical guidelines for health professionals on the safest and most effective use of vaccines in their practice. These recommendations are developed by the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) and endorsed by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

There is a specific section within the handbook for Vaccination of women planning pregnancy, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and preterm infants.

- Links: AIH 10th edition (June 2015) | V3.3.2 Vaccination of women who are planning pregnancy, pregnant or breastfeeding, and preterm infants (June 2015) | AIH 9th edition (2008)

| Australian Child Immunisation Programs 2013 | |

|---|---|

| Age | Vaccine |

| Birth |

|

| 2 months |

|

| 4 months |

|

| 6 months |

|

| 12 months |

|

| 18 months |

|

| 4 years |

|

| Notes: | Information provided for educational purposes only. Postnatal - Vaccination | Immunise Australia Program

a Hepatitis B vaccine: should be given to all infants as soon as practicable after birth. The greatest benefit is if given within 24 hours, and must be given within 7 days. b Rotavirus vaccine: third dose of vaccine is dependent on vaccine brand used. |

| Source: | Australian Immunisation Handbook 10th edition (April 2013).[11] National Immunisation Program Schedule From 1 February 2013 to 30 June 2013 PDF Immunise Australia Program. |

NSW

There have been significant changes to the vaccines offered in the NSW vaccination program over time:

- 1988, NSW conducted a Bicentennial measles campaign which offered measles vaccine to all child care and primary school age children.

- 1998 the national Measles Control Campaign, which was the first national mass vaccination program since the 1950s polio campaigns, offered measles, mumps, rubella vaccine to all primary school children laying the groundwork that has resulted in the World Health Organization declaration of measles elimination in Australia

- 2003 the meningococcal C vaccine was offered to all 1 – 19 year olds over a two year period

- 2004 a hepatitis B vaccine catch up program was conducted for Year 7 students who had not received a primary course of vaccine and continued until 2013.

- 2007 the three-dose course of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was offered to female students in Years 10-12 . In 2008 it was offered to female students in Years 7 – 10, and routinely to female students in Year 7 from 2009 and was introduced routinely for male students in Year 7 in 2013 with a catch-up program for male students in Year 9 in 2013 and 2014 only

- booster dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (dTpa) vaccine was offered to students in Years 7-12 in 2004, in Year 7 in 2005, in Year 10 from 2009-2012 and has been routinely offered to students in Year 7 from 2010 onwards

- catch-up dose of varicella (chicken pox) vaccine has been offered to students in Year 7 since 2006

(From NSW Health - Communicable Diseases)

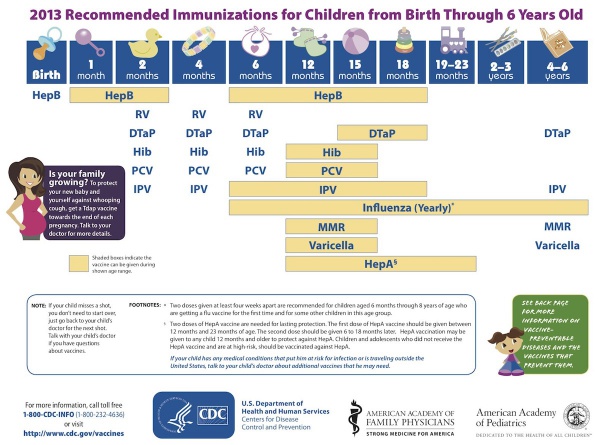

USA Recommended Immunizations for Children

(Birth through 6 years)

- Links: Vaccines | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Recommended Immunization Schedule for Persons Aged 0 Through 18 Years — United States, 2013

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Australian Immunisation Handbook 10th edition (2015) Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health. ISBN: 978-1-74241-861-2 Online ISBN: 978-1-74241-862-9.

- ↑ Albertsen N, Lynge AR, Skovgaard N, Olesen JS & Pedersen ML. (2020). Coverage rates of the children vaccination programme in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health , 79, 1721983. PMID: 32000619 DOI.

- ↑ Getahun D, Fassett MJ, Peltier MR, Takhar HS, Shaw SF, Im TM, Chiu VY & Jacobsen SJ. (2019). Association between seasonal influenza vaccination with pre- and postnatal outcomes. Vaccine , , . PMID: 30799158 DOI.

- ↑ Zhong Z, Haltalli M, Holder B, Rice T, Donaldson B, O'Driscoll M, Le-Doare K, Kampmann B & Tregoning JS. (2019). The impact of timing of maternal influenza immunization on infant antibody levels at birth. Clin. Exp. Immunol. , 195, 139-152. PMID: 30422307 DOI.

- ↑ Fathima P, Snelling TL, de Klerk N, Lehmann D, Blyth CC, Waddington CS & Moore HC. (2019). Perinatal Risk Factors Associated With Gastroenteritis Hospitalizations in Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Children in Western Australia (2000-2012): A Record Linkage Cohort Study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. , 38, 169-175. PMID: 29620723 DOI.

- ↑ Fortner KB, Nieuwoudt C, Reeder CF & Swamy GK. (2018). Infections in Pregnancy and the Role of Vaccines. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. , 45, 369-388. PMID: 29747736 DOI.

- ↑ Ford JH, Li M, Scheil W & Roder D. (2019). Human papillomavirus infection and intrauterine growth restriction: a data-linkage study. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. , 32, 279-285. PMID: 28889772 DOI.

- ↑ Irving SA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG, Mascola MA, Baggs J, DeStefano F, Cheetham TC, Jackson LA, Naleway AL, Glanz JM, Nordin JD & Belongia EA. (2013). Trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and spontaneous abortion. Obstet Gynecol , 121, 159-65. PMID: 23262941 DOI.

- ↑ Rubinstein F, Micone P, Bonotti A, Wainer V, Schwarcz A, Augustovski F, Pichon Riviere A & Karolinski A. (2013). Influenza A/H1N1 MF59 adjuvanted vaccine in pregnant women and adverse perinatal outcomes: multicentre study. BMJ , 346, f393. PMID: 23381200

- ↑ Mullooly JP, Schuler R, Mesa J, Drew L & DeStefano F. (2011). Wheezing lower respiratory disease and vaccination of premature infants. Vaccine , 29, 7611-7. PMID: 21875634 DOI.

- ↑ Australian Immunisation Handbook 10th edition (April 2013) Immunise Australia Program

Journals

Vaccine is the journal for those interested in vaccines and vaccination. Homepage | PubMed

Reviews

Bozzo P, Narducci A & Einarson A. (2011). Vaccination during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician , 57, 555-7. PMID: 21571717

Hamlin J, Senthilnathan S & Bernstein HH. (2008). Update on universal childhood immunizations. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. , 20, 483-9. PMID: 18622208 DOI.

Articles

Akinsanya-Beysolow I, Jenkins R & Meissner HC. (2013). Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended immunization schedule for persons aged 0 through 18 years--United States, 2013. , 62, 2-8. PMID: 23364302

Pham H, Geraci SA & Burton MJ. (2011). Adult immunizations: update on recommendations. Am. J. Med. , 124, 698-701. PMID: 21658665 DOI.

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

WHO Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011-2020

- "The Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) ― endorsed by the 194 Member States of the World Health Assembly in May 2012 ― is a framework to prevent millions of deaths by 2020 through more equitable access to existing vaccines for people in all communities"

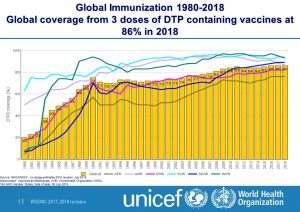

During 2018:

- Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP3) vaccine to about 86% of infants worldwide (116.3 million infants) protecting them against infectious diseases that can cause serious illness and disability or be fatal. By 2018, 129 countries had reached at least 90% coverage of DTP3 vaccine.

- Hib vaccine had been introduced in 191 countries. Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) causes meningitis and pneumonia. Global coverage with 3 doses of Hib vaccine is estimated at 72%. There is great variation between regions. The WHO Regions of the Americas and South East Asia are estimated to have 87% coverage, while it is only 23% in the WHO Western Pacific Region.

- Rotavirus vaccine was introduced in 101 countries by the end of 2018, including four in some parts of the country. Global coverage was estimated at 35%. Rotaviruses are the most common cause of severe diarrhoeal disease in young children throughout the world.

Australia

- Department of Health and Ageing Immunise Australia Program The Immunise Australia Program aims to increase national immunisation rates by funding free vaccination programs, administering the Australian Childhood Immunisation register and communicating information about immunisation to the general public and health professionals.

- Australian Immunisation Handbook. 9th edition (2008) | AIH 10th edition (April 2013)

- 2.3 Groups with Special Vaccination Requirements updated July 2009

Canada

United Kingdom

- Department of Health Immunisation information | Green Book and Vaccine Update

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation

USA

- CDC Vaccines | Immunization Schedules | Possible Side-effects from Vaccines | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Recommended Immunization Schedule for Persons Aged 0 Through 18 Years — United States, 2013

Terms

- Children Vaccination Programme (CVP) BCG: Bacille Calmette-Guerin; :

- Electronic medical Record system (EMR)

- Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis, Polio, Haemophilus influenza B (DTPHiB)

- Hepatitis B (HBV)

- Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)

- Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR)

- Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP)

- The WHO European Vaccine Action Plan (EVAP)

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Postnatal - Vaccination. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Postnatal_-_Vaccination

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G