Book - Manual of Human Embryology 17-10

| Embryology - 28 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Grosser O. Lewis FT. and McMurrich JP. The Development of the Digestive Tract and of the Organs of Respiration. (1912) chapter 17, vol. 2, in Keibel F. and Mall FP. Manual of Human Embryology II. (1912) J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

B. The Development of the Respiratory Apparatus

By Otto Grosser, of Prague.

| Online Editor pages |

|---|

Prof. Otto Grosser (1873- 1951) was an Austrian anatomist and embryologist. In 1907 he was appointed extraordinary professor at the German University in Prague, becoming ordinarius of anatomy there in 1909.

|

I. The Earliest Anlage

The first anlage of the respiratory apparatus appears caudal to the pharyngeal pouches as a median ventral groove; the oral portion of this forms a ridge on the outer surface of the epithelial tube, but its caudal end is more rounded and hemispherical (Figs. 317, 318, and 331). In the region of the groove the epithelium is thickened. The ridge-like portion is the laryngotracheal groove and the rounded end the unpaired anlage of the lungs. These structures make their appearance very early, simultaneously with the last pharyngeal pouches and before the formation of the last two closing membranes, and show at first no connection whatever with the pharyngeal pouch region, except that the anterior end of the laryngotracheal groove extends just to the aboral part of the mesobranchial area. During the further development of the anlage the lungs grow much more rapidly than the remaining parts and form an unpaired, almost spherical vesicle (Figs. 332 and 333), which is in connection with the digestive tract dorsally and passes over into the tracheal groove orally.

The question as to whether the mammalian lung anlage is paired or unpaired has been answered in the latter sense almost unanimously by authors who have written since Kolliker's time, and may be regarded as definitely established for the human embryo by the observations of Blisnianskaja (1904) and Broman (1904) and the models figured here. 29 The view of most authors (compare Narath 1901 and Flint 1906), that the anlage is from the beginning asymmetrical, is not borne out by the models, since the asymmetry shown in Figs. 318 and 331 and limited to the laryngotracheal groove is produced by a torsion of the digestive tube at the boundary between the head and trunk, and is practically wanting in Fig. 332.

The unpaired character of the lung anlage marks the great difference that exists between the lungs and the gills. The unpaired anlage of the mammal[1] is, 29 Thompson (1907) ascribes a paired anlage to the embryo from which Fig. 331 is taken, but does not figure it, and this statement has been transferred to the Normentafel. That he has, however, made a mistake as to the position of the lung anlage is apparent from his own description and from a figure published later (1908) ; he identifies it in 1908 as the stomach anlage, while in 1907 he transfers the lung anlage to the region of the diverticulum doubtfully identified in Fig. 331 as a fifth pharyngeal pouch. The embryo has, however, no stomach anlage; probably also his model was made on too small a scale. Fig. 145 of Broman (1904) agrees essentially with my Fig. 331.

it is true, probably a secondary condition, for in other lung-breathing animals, and among these in the lowest Tetrapoda, the amphibia, the anlage is paired (Remak, G-oette). Nevertheless even in these forms it is not to be homologized with a final (sixth or seventh) pharyngeal pouch, but is to be derived from a swim -bladder ; probably this structure was originally generally paired, and has, as a rule, become permanent only unilaterally (Greil, 1905).

Two longitudinal grooves (boundary grooves) on the lateral walls of the anterior part of the digestive tract mark out at an early period a ventral respiratory from a dorsal digestive zone (Kolliker, Flint; compare Fig. 333 and the transverse section of the region in Fig. 317, where the left groove is already indicated).

The unpaired anlage of the lung has, however, only a short existence; from it there develop laterally and caudally the two pulmonary sacks. The boundary furrows of the respiratory anlage at the same time begin to be more sharply defined, and first the lung anlage and then the tracheal groove become separated from the oesophagus by a septum that grows forward from below. Orally, however, the laryngeal portion of the groove encroaches more upon the mesobranchial area (p. 449) until it lies between the medial ends of the fourth branchial arches and later between those of the third. The respiratory apparatus now consists of the cleft-shape entrance of the larynx lying between the caudal pharyngeal pouch complexes, of the relatively long and slender laryngotracheal tube, 31 and of the two pulmonary sacks.

II. The Trachea

No striking modifications occur later in the tracheal tube. Its lumen is at first cylindrical (Fig. 341), but later, with the development of the membranous dorsal wall, it becomes heart- or horseshoe-shaped in transverse section (Fig. 330), and in older embryos (more than 30 mm. in length) the dorsal wall is always thrown into longitudinal folds. The epithelium undergoes no marked changes, except that it develops cilia. The glands appear at the close of the fourth month, almost simultaneously with the elastic fibres of the mucous membrane, and very soon become hollow; the formation of glands appears to continue throughout pregnancy. The tracheal cartilages make their appearance in the places where they are finally found; their anlagen are to be recognized as condensations of the tissue in embryos of 17 mm., and cartilage appears in embryos of 20 mm. The differentiation is always more advanced in the neighborhood of the larynx (Philip, Kolliker, cited by Merkel, 1902). Musculature occurs in the dorsal wall of the trachea before the rings become cartilaginous. (For further details see Merkel, 1902.) 81 The occurrence of the cesophagotracheal septum and the anomalies that are occasionally associated with its formation have already been briefly discussed by F. T. Lewis in a preceding section of this chapter.

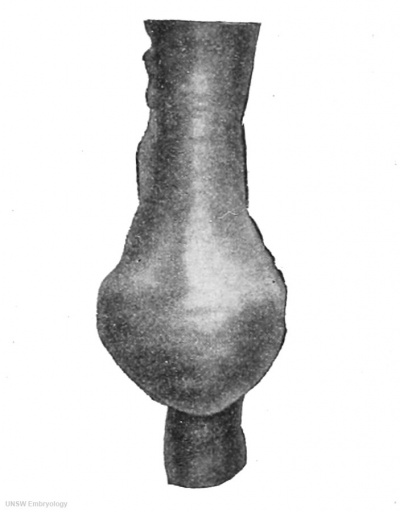

| Fig. 332. — Lung anlage of an embryo of 4.25 mm. vertex-breech measurement, from the ventral side. Embryo R. Meyer No. 399 of the Zurich Anatomical Institute (Stage I of Blisnianskaja). X 150. | Fig. 333. — The same model seen from the left side. The outlines of the lumen shown by the broken line. X 150. |

No evidence is furnished by human embryos nor yet by those of the Plaeentalia in general in favor of a derivation of the tracheal skeleton from that of the larynx, that is to say from the cartilago lateralis of the amphibia. In Echidna Goppert (1901) has found a union of the prechondral rings by paired prsechondral cords and consequently their differentiation from a common anlage.

III. The Larynx

The skeleton and musculature of the larynx have already been considered in the first volume of this Handbook ; the differentiation of the entrance of the larynx and of the laryngeal cavity remains to be considered here.

The oral end of the laryngotracheal groove shortly after its formation becomes embraced by two swellings, the arytenoid swellings (Kallius; crista terminalis, His). They indicate also the caudal limits of the branchial portion of the intestine, characterized by its lateral widening. The caudal pharyngeal pouch complex lies at first craniolaterally to the swellings, which are at first actually only the somewhat more pronounced borders of the oral end of the laryngotracheal groove (Kolliker, Soulie and Bardier). After the formation of the oesophago tracheal septum the swellings persist as the boundary of the laryngeal groove, and between them the groove deepens, its margins come into apposition, and its epithelium fuses, producing an obliteration of the cavity of the larynx (see below). At the time when the swellings lie almost parallel with one another, there may be distinguished, according to Soulie and Bardier (1907), at about their middle a thickening (arytenoid tubercle, bourrelet arytenoidien) and orally a narrower part, the later plica ary-epiglottica. By these the region of the laryngeal entrance becomes early delimited from that of the later interarytenoid notch. Anteriorly the swellings at first pass into the mesobranchial area and later they bend in this area in an arch-like manner to form a transverse swelling lying in front of the laryngotracheal groove. This, the furcula of His, is perhaps to be interpreted as the copula region of the branchial arches (see p. 454 and Kallius, 1910). This separates into the root of the tongue anteriorly and the anlage of the epiglottis posteriorly (Haimnar, 1902). In the median line the boundary furrow between these two structures is less deep than it is laterally, and there is thus formed the anlage of the plica glosso-epiglottica media, which, however, becomes more sharply denned only after birth (Kallius, 1897; Soulie and Bardier). The epiglottis lies at first between the fourth branchial arches; to what extent the third arches are concerned in its formation is still in dispute. A temporary median furrow would appear to indicate that it has a paired anlage, but this disappears very soon (Soulie and Bardier).

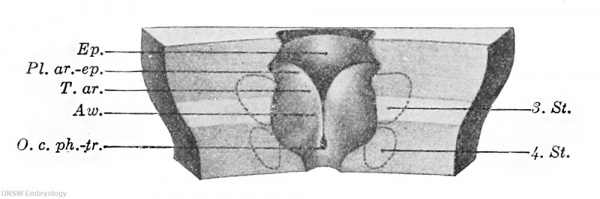

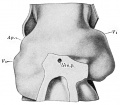

Fig. 334. — Entrance to the larynx of an embryo of 8 mm. (After Soulie and Bardier, 1907.) Aw., arytenoid swelling; Ep., epiglottis; O. c. ph.-tr., orifice of the canalis pharyngotrachealis; PI. ar.-ep., plica ary-epiglottica; 8., 4- St., third and fourth pharyngeal pouches (their boundaries indicated schematically by dotted lines); T.ar., tuberculum aryteuoideum. X 30.

Whether the epiglQttis is formed from a growth of the arches into the mesobranchial area (the view of the majority of authors; compare Soulie and Bardier), or as an elevation of this area itself, it being independent of the arches (His, F.c. Hammar), is not yet definitely determined, and, furthermore, the first developmental processes of the entrance to the human larynx are not yet thoroughly known. — Kallius (1897), with His and others, derives the arytenoid swellings from the last (sixth) branchial arches (he names them the fifth, since the fifth pouch and the fifth aortic arch were at that time scarcely known). The manner of their formation contradicts this, however. The opinion of Kohlbrugge, cited by Kallius, that the ventriculus laryngis is a branchial pouch and therefore the caudal boundary of the arch mentioned, is untenable in view of the late appearance of the ventricle. At all events the material of the sixth arch, which is undoubtedly present (on account of its aortic arch), must pass continuously into that of the arytenoid swelling, since a separating sixth pharyngeal pouch is to be seen (see above, p. 446, 452).

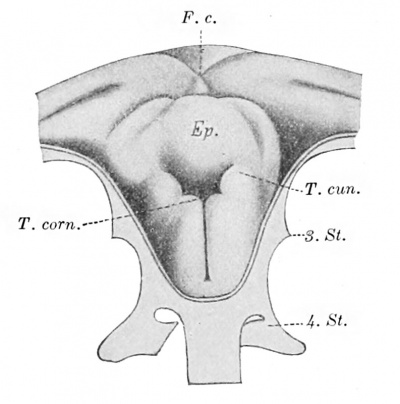

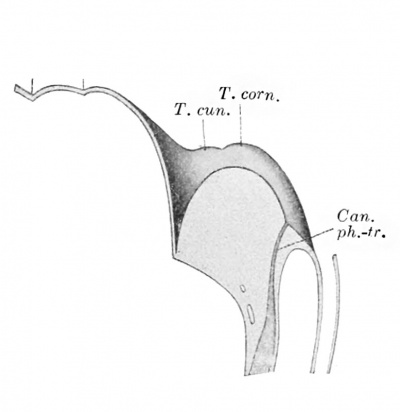

| Fig. 335. — Laryngeal entrance of an embryo of 28 to 29 days (8-9 mm.). (After Kallius, 1897.) Ep., epiglottis; F. c, foramen caecum; 8., 4- "St., third and fourth pharyngeal pouches; T . corn., tuberculum corniculatum. X 33. | Fig. 336. — Median section of the larynx shown in Fig. 335. (After Kallius, 1S97.) Can. ph.-tr., canalia pharyngotrachealis. The remaining lettering as in Fig. 335. X 33. |

Frazer (1910) comes to results which are in general quite similar, but, owing to the employment of a peculiar nomenclature, they are not easily compared with those of others. He also lays special stress on the identity of the arytenoid swellings with the last branchial arches, but later on allows also the ventral ends of the fourth arches to participate in the formation of the swellings. The epiglottis he derives principally from the third arch.

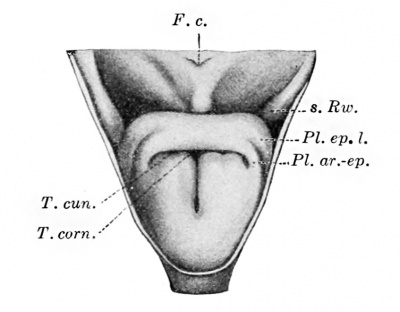

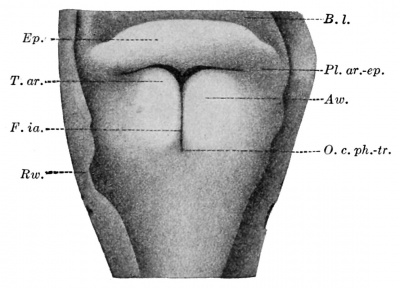

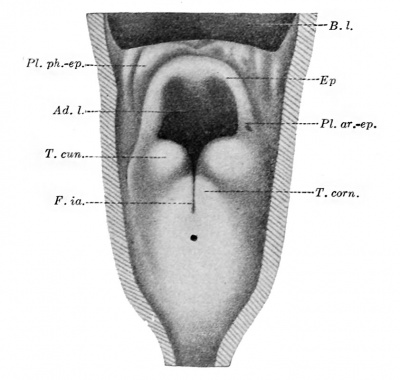

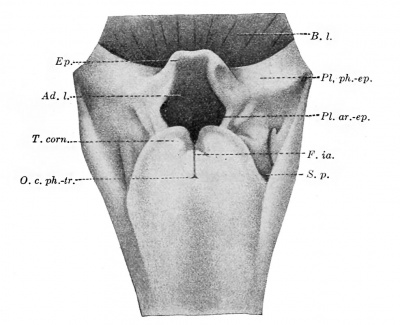

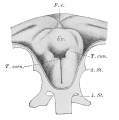

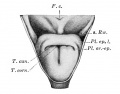

After the formation of the arytenoid swellings and the epiglottis the evolution of the larynx can be followed more thoroughly. The arytenoid swellings gradually become folded in the middle almost to the extent of a right angle, so that the caudal portions become parallel while the oral ones diverge more and more (Figs. 334 and 335). While this process is going on, they move forward and their oral portions apply themselves to the aboral surface of the epiglottis, with which the folds are connected by the plicae ary-epiglotticse. The aditus laryngis has thus assumed the form of a T-shaped cleft (Figs. 334 to 338 and 325) ; the horizontal limb of the T lies between the arytenoid swellings and the epiglottis, the vertical one between the aboral portions of the two swellings (interarytenoid notch). At this time, however, the cleft ends blindly, since the epithelium of the laryngeal entrance has fused (Figs. 326 and 327). At the points where each arytenoid swelling is folded there is a tubercle, the tuberculum corniculatum of Kallius or the tub. arytcenoideum of Soulie and Bardier. Lateral to this a second tubercle, the tuberculum cuneiforme, appears, according to Kallius, in embryos of 8-9 mm., but according to Soulie and Bardier, only much later, in fetuses of about 40 mm. (Compare Figs. 334—339.) Kallius finds also about this time the plicce epiglottic^ laterales, extending from the anlage of the epiglottis toward two lateral folds of the mucous membrane of the pharynx (lateral phamygeal swellings) (Fig. 337) ; Soulie and Bardier do not, however, perceive these folds (Fig. 338). In fetuses of about 40 mm. the fusion of the laryngeal walls becomes dissolved, the tubercles of the arytenoid swellings withdraw from contact with the caudal surface of the epiglottis, and the entrance of the larynx becomes oval (Fig. 339). Later, according to Kallius, the lateral plicae epiglotticse unite with the lateral pharyngeal swellings to form the plicce pharyngo-epiglotticce, probably as a result of the descent of the larynx; at all events, these folds become very distinct later on (Fig. 340) and are even much higher in the new-born child than in the adult. The plicce glosso-epiglotticce laterales separate from these, according to Soulie and Bardier, in fetuses of more than 29/43 cm.

Fig. 337. — The entrance of the larynx in an embryo of 40-42 days (15-16 mm.). (After Kallius, 1897.) PL ar.-ep., plica ary-epiglottica; PL ep. L, plica epiglottica lateralis; s. Rw., lateral pharyngeal swelling. The remaining lettering as in Fig. 335. X 15.

According to Frazer (1910), the cuneiform tubercle corresponds to the medial end of the fourth arch, the corniculate tubercle to that of the fifth. The transverse limb of the T-shaped laryngeal cleft represents a portion of the pharyngeal cavity, whose caudal boundary in the adult would be represented by the free edge of the true vocal cord and a line drawn from one tip of the processus vocalis to the apex of the arytenoid.

Kallius finds in the lateral plicae epiglotticae the similarly named, skeletonless portion of the epiglottis observed by Groppert in the lower mammals; the folds remain recognizable throughout life in the majority of the mammals, oral to the plicae arj-epiglotticae. The lateral pharyngeal swellings may be phylogenetic representatives of the plicae palatopharyngeal of the mammals (Goppert).

Fig. 338. — Entrance of the larynx of an embryo of 30 mm. From a dissection. (After Soulid and Bardier, 1907.) Aw., arytenoid swelling; B. I., base of the tongue; Ep , epiglottis; F. ia., fissura interarytaenoidea; O. c. ph.-tr., orifice of thepharyngotracheal canal; PL ar.-ep., plica ary-epiglottica; Rw., wall of pharynx. X 20.

The shape of the cavity of the larynx changes considerably during development. The cleft-shaped lumen of the laryngeal groove becomes obliterated, as has been stated, by the arytenoid swellings coming into apposition and by the fusion of their epithelium (compare Figs. 325-327). Nevertheless, this epithelial fusion, first described by Roth (1880), is in the beginning, at least, by no means complete (Fig. 336) : on the one hand, there remains orally, between the arytenoid swellings and the epiglottis, a funnelshaped cavity which usually ends blindly ventro-caudally ; on the other hand, a fine canal persists in the epithelium along the posterior wall of the larynx, beginning at the interarytenoid notch and passing, with a gradual enlargement, into the tracheal lumen (embryo of 8-9 mm., according to Kallius; canalis pharyngotrachealis of Soulie and Bardier; Figs 334—338). Frequently, however, even in this stage and also later, complete fusion occurs (compare the thorough account by Fein, 1903). The fusion extends caudally beyond the region of the glottis, — that is to say, to tne region of the vocal cords, and its lower boundary may correspond vvith the linea arcuata inferior, described by Eeinke and occasionally perceptible even in the adult (Kallius). According to Soulie and Bardier, however, the fusion for a time extends downward as far as the region of the cricoid cartilage (embryos of 19 mm.). The fusion gradually dissolves in embryos between 17 and 40 mm. (Fein; ; indeed it perhaps begins somewhat earlier (Kallius), the solution showing itself at first as small spaces in the line of fusion. It results probably from a breaking down of cells. (Fein). Kallius mentions the incisura interarytamoidea as one of the places where the fusion persists for a long time, but Fein contradicts this statement.

Fig. 339. — Entrance of the larynx of an embryo of 16/23 cm., male. From a dissection. (After Soulie" and Bardier, 1907.,) Ad. I., aditus laryngis; PI. ph.-ep., plica pharyngo-epiglottica. The remaining lettering aa in Fig3. 335 and 338. X 6.

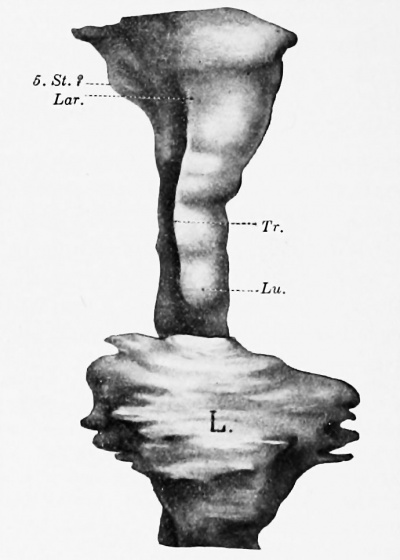

A satisfactory explanation of the epithelial fusion in the larynx has not yet been given. A difference from the epithelial fusions in other portions of the body exists in this case, in that an epithelial proliferation does not precede it; the epithelium is simply compressed between the mesodermal arytenoid swellings, its nuclei are arranged parallel to the mesodermie surface (Kallius). On account of its transitiveness it cannot be regarded as a protective phenomenon. Compare also V. Schmidt (1910).

The vocal cords are recognizable when the fusion is completely dissolved; the anlage of the ventriculus laryngis indicates their position. According to Soulie and Bardier, the anlage of the ventricle appears in embryos of 24 mm. as a solid epithelial bud, which acquires an independent lumen at the beginning of the third month; this later unites with the lumen of the larynx by its epithelial stalk becoming hollow. Accordingly the ventricle has for a time the form of a spherical vesicle with a cylindrical stalk ; but in a fetus of 44/57 mm. the typical form occurs. The ventricle makes its appearance earlier than the date Kallius assigns to it (middle of the fourth month) ; Hansemann (1899) finds it in an embryo of 27 mm. as a blind sack. The distinct delimitation of the vocal cords first occurs, however, in the middle of the third month (fetus of 37 mm., according to Soulie and Bardier) ; their epithelium differs from that of the surrounding regions, after stages of 45-50 mm., by the absence of cilia. Elastic fibres and a distinct musculature first appear at about the middle of pregnancy; yet at birth the free edge of the vocal cord is rounded and only assumes its definitive form within the first six months of extra-uterine life. According to Frazer (1910), a prechondral "node" occurs imbedded in the ventral ends of each cord during the second fetal month; these disappear later. — The plicce ventricular es form at first, after the formation of the ventricle, roundish elevations, in which glands appear in the fourth month. The ciliated epithelium with which they are covered is replaced by a squamous epithelium in the course of the first year.

Fig. 340. — Entrance of the larynx of an embryo of 29/43 cm., male. From a dissection. (After Soulie and Bardier, 1907.) S. p., sinus piriformis. The remaining lettering as in Figs. 335, 338, and 339. X 3.

The epithelium of the larynx caudal to the region of fusion rests at first close upon the cricoid cartilage (embryos of about 20 mm.; compare Fig. 330); later a rather thick layer of loose connective tissue becomes interposed between the epithelium and the cartilage (fourth month, according to Kallius). The cricoid cartilage at this time consequently grows more rapidly than its epithelial lining, but later again is equalled by it.

The entire larynx in embryos from about 8 mm. onward is proportionately large and only acquires its proper dimensions after birth (Kallius, Merkel). It is much higher in embryos and fetuses than in the adult, and in the fifth month projects into the pharyngonasal cavity, whereby the epiglottis rests upon the dorsal surface of the soft palate as in most mammals. At the time of birth the descent of the larynx is not yet completed ; the glottis in the new-born child is at about the level of the disk between the second and third cervical vertebra, while in the adult it is in front of the fifth vertebra. This relation, however, is subject to some slight individual variation (compare Merkel, 1902).

IV. The Lungs

After the lung anlage has become paired two pulmonary sacks or vesicles are to be distinguished, and at first these appear to be symmetrical (compare Fig. 157 of Broman, 1904). Very soon, however, they become unsymmetrical, the right one becomes larger and bends caudally and dorsally, while the left at first has an almost transverse position (in embryos of 5 mm.; compare Fig. 341, and also Fig. 2 of Blisnianskaja and Fig. 170 of Broman). Each pulmonary sack ends in a swollen flask-shaped stem bud.

Our morphological knowledge of the arrangement of the bronchial system does not date further back than Aeby (1880), whose results, apart from the establishment of a special " eparterial " bronchial system, have been confirmed by later investigations. The account that follows is based especially upon the unsurpassed work of Narath (1901). Unfortunately, the number of human embryos studied by this author was very small, and the figures of Blisnianskaja (1904) that have since been published are rather incomplete. More recent investigations and figures of the development of the human lungs, especially in later stages, are wanting.

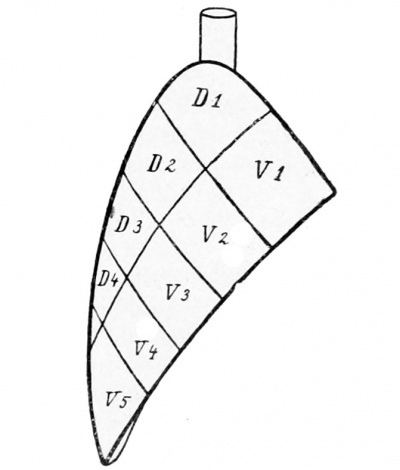

A short statement as to the nomenclature used in describing the branchings of the bronchi may be given. The stem bud is the anlage of the stem bronchus, which traverses the entire lung and from which branches or lateral bronchi are given off. These extend out in the four principal directions and are either direct or indirect lateral bronchi (bronchi of the first or second order; the latter also known as accessory bronchi) ; they are repeated at approximately regular intervals (Aeby). Each group of lateral bronchi given off, according to the principal directions at approximately the same level, constitutes one of the stories or tiers of the lung; they are perhaps genetically related (Narath). The most important and strongest lateral bronchi are those termed ventral by Aeby ; they arise laterally and extend at first laterally, but later supply the ventral region of the lung and also in its oral portions pass more or less to the ventral side; they lie ventral to the main stem of the pulmonary artery. On this account Narath has retained Aeby's name for them, while other authors (His, Robinson, d'Hardivillier, Flint) term them lateral or external bronchi. Toward the end of the stem bronchus they pass more and more toward its dorsal surface; a line connecting their origins would therefore have a spiral course, an arrangement that is repeated in the other bronchi and in the course of the arterial stem. The second most important group is that of the dorsal bronchi, which arise orally to the corresponding ventral bronchi from the dorsal surface of the stem bronchus, and are not infrequently represented by several branches in each lung tier. The apices of the lungs are supplied by apical bronchi (Narath) ; their significance is still disputed. The right apical is Aeby's eparterial bronchus, and in that author's opinion is a special element not represented elsewhere in the lung, while Narath regards it as the first dorsal bronchus (see below). In addition there occur ventral and dorsal accessory bronchi (lateral bronchi of the second order), whose importance is small and whose formation is quite irregular. The ventral ones have been regarded as direct outgrowths from the stem bronchus and have been termed by His and Flint, for example, simply ventral bronchi, in contrast to the lateral ones (Aeby's ventral). Among them one, the infracardial bronchus, is especially well developed and worthy of mention. Flint (and also d'Hardivillier) regard the dorsal accessory bronchi also as direct medial branches of the bronchus.

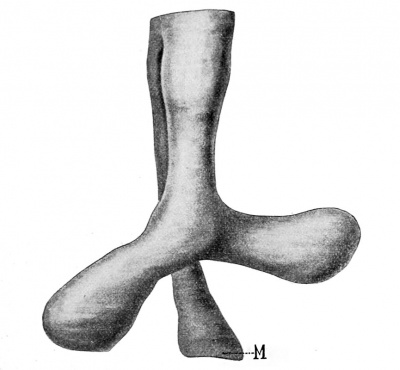

Fig. 341. — Epithelial lung anlage of the embryo Rob. Meyer 338 (Normentafel No. 18. 5 mm.), from the ventral surface. M, stomach. X 100.

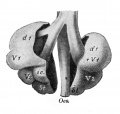

The first lateral bronchus formed is the first ventral (lateral) one of the right side (Narath) ; yet the stage of the human embryo in which it is alone present has not yet been described. 32 Shortly after this laterally directed anlage and proximal to it there appears the smaller right apical bronchus and, in the left lung, the first ventral bronchus (Narath, embryo of 7 mm., Fig. 342). At the point of origin of the anlagen (buds) of the ventral bronchi the stem bronchus is distinctly bent medially. The anlage of the (right) apical bronchus is well separated from that of the first ventral bronchus in the stage represented in Fig. 342, 33 but it flattens out toward the trachea. The right stem bronchus is markedly longer than the left. This stage corresponds approximately to the youngest figured by His (1887), but differs in form and proportion somewhat from His's figure.

- Perhaps Fig. 2 of Blisnianskaja (1904) represents such a stage. The text lacks a definite statement.

- Blisnianskaja describes a stage in which the right apical bud is seated on the ventral one.

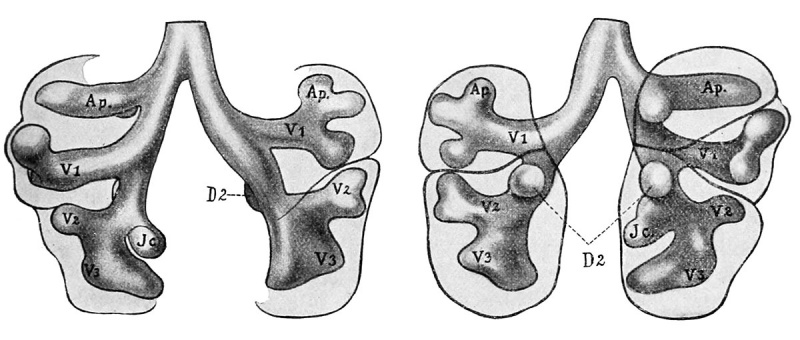

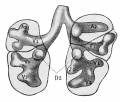

An embryo of 11 mm (Normentafel No. 45), whose bronchial tree almost exactly agrees with that shown in Figs. 343 and 344, had, according to Narath, on the right side the apical bronchus (Ap.), extending dorsolaterally and with three buds, the purely lateral first ventral bronchus (V\) with two buds, the purely dorsal second dorsal bronchus {D 2 ) with two buds, the infracardial bronchus (Jc) between D 2 and V 2 , directed ventromedial^ and with indications of buds, and then V 2 and V 3 , both undivided, as is also the stem bud; on the left there is the first ventral bronchus, passing laterodorsally and having a strong dorsal branch, the left apical bronchus; at the origin of this V x bends sharply ventrally. The ends of both show lateral buds. Then follow D 2 passing dorsally, V 2 passing laterally and having at its root what is perhaps the anlage of a left infracardial bronchus, and Y 3 , as well as the stem bud, which does not extend quite so far caudally as that of the right side.

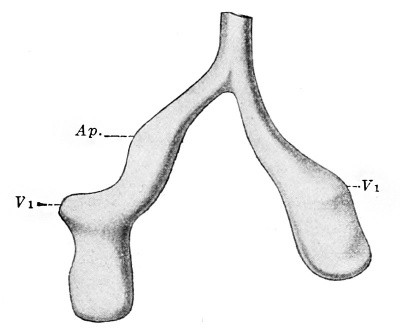

Fig. 342. — Epithelial lung anlage of the embryo Chr. 1 (Normentafe No. 28.7 mm.;. (After Narath, 1901.) Apparently the plates have been somewhat displaced in preparing the model; the right stem bronchus should descend more directly than the left (Narath). Ap., apical bud; Vi, first ventral bud. X 100.

In an embryo of 15.5 mm Narath found in the right lung Ap.—V—D—Jc—V 2 —V ?i , and in the left V 1 ~D 2 —Jc—V 2 — V z — D 4 — F 4 and also a small bud which was perhaps an accessory bronchus from V 4 . This stage, though slightly older than that shown in Fig. 345, is very similar to it. The left lung is at first decidedly more advanced in the development of its deeper parts, as His has pointed out. V 1 on the left side bears the strong, dorsally directed apical bronchus. The left infracardial bronchus, which has become interposed in the series, arises from the ventral side of the stem bronchus close to V 2 and already possesses three buds. D z is wanting on both sides. — Altogether Narath finds in each lung from four to five ventral bronchi, a sixth rarely forming in the left lung; the dorsal bronchi are usually fewer, frequently only two on each stem bronchus. An infracardial bronchus occurs on the right side as a rule, but is rare on the left, and its presence there in the embryo just described must be regarded as an anomaly. Its suppression on the left side appears to be due to the position of the heart and pulmonary vein on the left side (Flint). Other ventral accessory bronchi appear only here and there. The infracardial bronchus belongs almost without exception to the second lung tier ; that it may occur in the left lung has been shown by Ewart and Schaffner, while the bronchus thus described by Hasse is identical with the distal part of the main stem of the left V x (Narath). The apical bronchus of the left side, leaving variations out of consideration, arises even from the beginning from V t , but in its branching it behaves throughout like the right apical, notwithstanding its smaller calibre (Narath).

Figs. 343 and 344. — Reconstruction of the lungs of an embryo at the beginning of the fifth week, ventral and dorsal views. (After Merkel, 1902.) Ap., apical bronchus; D\, Dz, etc., dorsal; Vi, Fj, etc. , ventral bronchi; Jc, infracardial bronchus. Fig. 343. | Fig. 344.

The point of bifurcation of the trachea and the entire lung anlage migrates caudally during the course of development. In the embryo described by Ingalls (1904) (Normentafel No. 14, 4.9 mm.) the lung anlage lies at the level of the third cervical segment, but in one of about one month it is already at the level of the first thoracic vertebra, according to Blisnianskaja. From that time onward the recession proceeds more slowly, the level of the fourth thoracic vertebra being reached at birth. The bifurcation angle of the trachea at first diminishes (compare Figs. 341 and 342), but increases again later (for numerical data see Blisnianskaja).

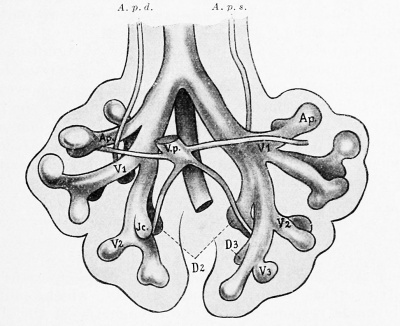

The pulmonary arteries in the youngest stages that have been studied (7 mm) arise, according to Narath, quite symmetrically from the last aortic arch at the level of the larynx anlage, and course downward along the trachea, diverging somewhat caudally ?.nd dorsally, the left being a little more dorsal than the right. In the region of the stem bud the left artery lies laterodorsally, the right laterally. Later (embryo of 11 mm.) the right vessel bends ventrally to avoid the apical bud, distal to this again lying lateral and then laterodorsal to the stem bronchus, while the left lies at first laterodorsal and then dorsal (see also Fig. 345). Still later the recession of the heart influences the course of the arteries; these no longer run caudally alongside the trachea, but approach the lungs more and more from the ventral side, and accordingly become bent around the bronchial tree until its branches prevent a continuation of the process. The first of these branches is on both sides the first ventral bronchus, the right apical bronchus, being always situated dorsal to the artery, having no such effect upon it.

The pulmonary veins form at first a single stem opening into the atrium (see the chapter on the development of the heart). Narath observed it coming out of the angle of bifurcation of the trachea in an embryo of 7 mm. (Fig. 348). In an embryo of 11 mm. there was a main vein on each side, situated ventromedially to the stem bronchus, and opening into it a transverse vein from the first lung tier (compare also Fig. 345, from His). By the common stem being taken up into the wall of the left atrium, all four principal veins finally open directly into the atrium. The course of the veins is also influenced by the recession of the heart; the vein from the upper lung tier is forced to descend, the main stems become partly bent around the stem bronchus and their proximal portions pass transversely to the heart.

The situation of the pulmonary veins ventromedially to the stem bronchus is determined by the heart, according to Flint, and their position again explains the dorsolateral course of the arteries. Flint, however, ascribes to the arteries no importance in determining the arrangement of the bronchial branching. Ontogenetically they certainly have no such influence, since the first lateral bronchi are formed before the arterial stems appear (Narath).

A number of important questions cannot be settled from the study of human embryos, partly because the necessary material is not yet available and partly because the questions are not to be settled by what takes place iu the highly modified human lung alone. The modification is due principally to the shortening of the trunk (G-. Ruge) ; the human lung is exceptionally short and broad, and consequently the stem bronchus is so overshadowed in the adult lung by the very long and strong branches, especially by the ventral bronchi, that it was for a long time believed that the branching was of the dichotomous type. The available embryonic material suffices to demonstrate the surpassing role of the stem bronchus during development; it also shows that the principal branches are formed not dichotomously but monopodially. The stem bronchus is throughout a continuous structure, whose undivided tip keeps on growing, while the lateral bronchi appear at some distance from it. Nevertheless, according to Narath, the stem bud always takes part in the formation of the lateral branches; the lateral bud always arises in its territory, and this is true not only for the stem bud, but also for the terminal buds of each lateral branch, and therefore for the entire branching. However, Narath did not study older stages with more than the fourth order of branches; for the later ones the occurrence of equal or unequal dichotomous divisions or of division even into three has been generally accepted (Kolliker, Merkel, Flint). These smaller branches, however, are so greatly under the influence of their surroundings that probably no very great importance is to be assigned to these departures from the main type. Indeed, such twigs, formed dichotomously, do not remain symmetrical (Flint). From Narath's conception of the branching certain further consequences relative to the significance of the stem bronchus follow. For only in the formation of the ventral bronchi does the stem bud participate, the dorsal bronchi and the ventral accessory ones, including the infracardial bronchi, arise from the stem bronchus frequently only after the formation of the corresponding ventral ones, or from the roots of the latter, and, at least in some cases, proximal "to these, so. that they are separated by them from the stem bud. Narath assumes, on the basis of comparative observations, that all these bronchi are primarily branches of the ventral ones and that they have secondarily become displaced on to the stem bronchus. This view is accepted by Blisnianskaja, while d'Hardivillier and Flint, for example, advocate the equivalency of all branches passing off in the principal directions and deny a migration of them. According to this the stem bronchus as well as the stem bud possesses a capability for branch formation. Narath 's conception of monopodial branching is, accordingly, somewhat different from that of the remaining authors; it is monopodial with acropetal development of the lateral buds. A final statement on this question can hardly be given here; indeed, it cannot be given on the basis of development alone.

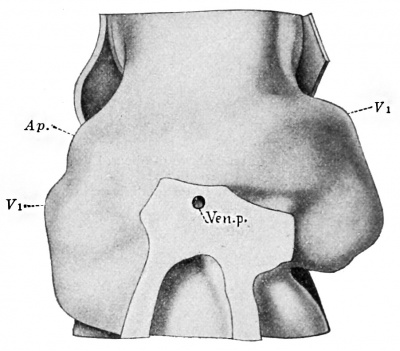

Fig. 345. — Anlage of the lung of embryo N (10.5 mm), seen from in front with arteries and veins. (After His, 1887.) A. p. d. and A. p. s., right and left pulmonary artery; V. p., pulmonary vein. The remaining lettering as in Fig. 343. X 50.

As already stated, Aeby assigns a special significance to the right apical bronchus, which he terms the eparterial bronchus. Its development and comparative anatomy show, however, that it is the first dorsal bronchus; the "crossing" of the stem bronchus by the artery distal to it does not occur in the lower mammals and occurs late ontogenetically, being dependent on the degree of recession of the heart (Narath). 34 More difficult of explanation are the relations on the left side. Most authors (most recently Pensa, 1909) assume either a lack of the corresponding bronchus of the left side or (d'Hardivillier) its degeneration. According to Narath, who derives the dorsal from the ventral bronchi, the left apical bronchus is possibly a true dorsal bronchus which, from some cause or other, perhaps the course taken by the arteries (the aortic arches and the ductus Botalli, which, indeed, are generally made responsible for the asymmetry of the first lung tier), has not been able to migrate on to the stem bronchus and, on account of the course of the left pulmonary artery, then arises from the ventral bronchus far from its origin. With this explana tion Blisnianskaja agrees. If this be the case, the upper lobe of the left lung is equivalent to the upper and middle lobes of the right. At all events, the idea of a special "eparterial" group of bronchi cannot be maintained.

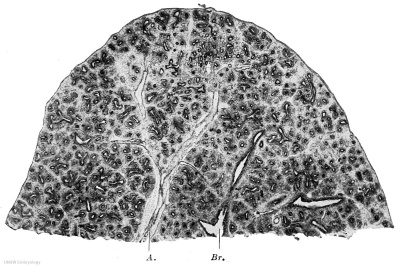

In the embryonic lung the abundance of connective tissue is very striking; the intervals between the relatively widely separated branches of the bronchi are filled with loose mesodermal tissue. This in the immediate vicinity of the epithelial tubes arranges itself concentrically around them and is here somewhat richer in cells than in the middle region between the bronchial rami (Fig. 346). With the progress of the bronchial branching the end buds become gradually smaller ; in the fourth month they have, according to Kolliker (quoted by Merkel, 1902), a diameter of 0.18 to 0.27 mm., in the beginning of the fifth month they measure only 0.09 to 0.13 mm., with a maximum of 0.15 mm. At about this time the lobules appear as the result of an increase of the embryonic connective tissue in the intervals between the areas of the bronchioles; the lobules in a fetus of 20 weeks have an

average diameter of 0.25 mm., according to Merkel (1902). At this stage of development the transverse sections of the larger branches are stellate, "the largest ones are lined by a ciliated epithelium. The cartilage plates in their walls do not extend beyond the first branches, nor do the gland anlagen. The muscles are distinctly recognizable from the surrounding mesodermic tissue. ' ' At the end of the sixth month the ends of the finer bronchi have a diameter of only 0.056 to 0.067 mm. and are very closely packed; they may already be termed alveoli (Kolliker). Their epithelium is low and the connective tissue in their immediate vicinity is still very rich in nuclei, although its quantity is on the whole greatly reduced. The cartilage formation extends in the sixth month far into the bronchial twigs, but the glands are still confined to the largest trunks (Merkel).

- Flint (1906) identifies the right apical bronchus, which arises from the trachea in the pig, as the first lateral bronchus (a ventral bronchus according to the nomenclature vised here), and sees in it the sole representative of the first lung tier, which is completely wanting on the left side. However, the course of the arteries is not sufficiently established and, furthermore, the question is not to be settled by what occurs in the pig, which in this respect is certainly not a primitive form.

Fig. 346. — Section through the lower lobe of the right lung of a fetus of 100 mm. vertex-breech length taken at right angles to the dorsal surface. Br., bronchus; A., artery. X 20.

According to Kolliker (quoted by Merkel), the further development takes place in the following manner : ' ' The formation of the air-cells and smallest lobes, beginning in the sixth month, is completed only in the last months of pregnancy, for while the aircells of the mature fetus are scarcely greater than in the sixth month, and measure only from 68 to 135 w, even in the lungs of new-born children who have already breathed the lobes themselves increase very markedly in size, so that the secondary lobes, which have a diameter of only 0.65 to 2.23 mm. in an embryo of six months, measure 4.5 to 9.0 mm. and over in the new-born child." The formation of new branches is, however, according to Merkel, scarcely to be followed in the later months, on account of the abundant foldings of the alveolar walls.

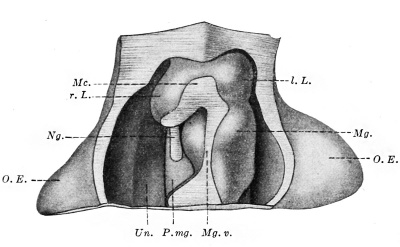

Fig. 347. — The mesodermal anlage of the lungs of an embryo of 5 mm (Normentafel No. 20). (After Broman, 1904.) The epithelial anlage, according to Broman, is almost identical with that shown in Fig. 341, except that it is more asymmetrical and the left lung is directed even a little cranially. t. L., I. L., right and left lung; Mc, posterior mesocardium; Mg., stomach; Mg. v., ventral mesogastrium; Ng., accessory (mesolateral) mesentery; O. E., upper limb; P. mg., plica mesogastrica; Un., mesonephros. X 35.

Elastic tissue is relatively late in making its appearance in the lung, according to Linser (1900), whose results, according to Merkel, agree essentially with those of Lenzi (1898). Already recognizable in the vessels in the third month, it appears at the beginning of the fourth month in the largest bronchi and increases slowly in amount ; in the middle of the fifth month its fibres first appear in the alveoli, and in the seventh they occur free in the stroma. The tissue does not stain as deeply as it does later on, and is to be regarded as young, immature elastic tissue, which becomes mature a few weeks after birth under the influence of use. At this time, too, an enormous increase in the number of fibres takes place. — The pulmonary arteries, which possess the typical structure before birth, afterwards come to resemble the pulmonary veins, owing to a reduction of their tunica media, the elastic tissue in the walls of the veins becoming increased in amount.

The formation of the lobes of the lung was first considered by Aeby and was first worked out by Narath. Their development in the human lung has been described principally by Blisnianskaja, although some important figures of very young stages have been given by Broman (1904).

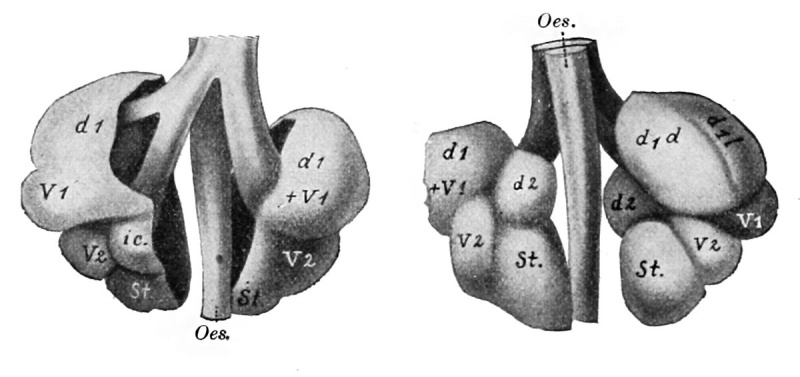

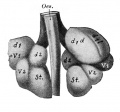

Aeby defines a lung lobe as follows : "A true lobe is never supported by more than a single lateral bronchus and therefore includes no portion of the stem bronchus." The "lower lobe" of the lung which contains the stem bronchus and most of the branches, without showing any corresponding markings on the surface, is termed by Aeby the "lung stem." Soon after the formation of the first lateral bud in the embryo, each bud becomes marked out upon the surface of the mesodermal anlage of the lung. This is a thick growth of mesoderm which projects on each side into the ccelom (see Vol. I, Chapter 13) and surrounds the epithelial pulmonary sack, surpassing it in volume, however, many times. At first, before the development of the lateral bronchi, the surface of this anlage is smooth and rounded (Fig. 347; for still younger stages see Broman, Figs. 144 and 146 for a 3.4 mm. embryo, and Figs. 156, 158, 160, and 162 for a somewhat further developed embryo of 3 mm.) ; later it becomes almost mulberrylike, since not only the buds of the first lung tier (Fig. 348), but soon also those of the following tiers produce elevations on the surface (Figs. 349 and 350). Only the youngest part of the lung appears for a time as the lung stem in Aeby's sense. With the development of the buds the mesoderm over their tips gradually diminishes in quantity, although the branches continue to be imbedded in an abundant mesoderm. A series of lateral and a series of dorsal elevations are especially marked, and after these the infracardial elevation. "Each primary elevation then becomes again divided into several secondary elevations 35 by the budding of the bronchial bud which it contains, and so the process goes on until the pulmonary wings become covered with fine granules. . . . With the growth of the lung these gradually disappear and the surface usually becomes smoother" (Narath). Only the first-formed furrows persist (Figs. 351 and 352), probably on account of the rapid and extensive growth of the first bronchi. Consequently in man only the first lung tier finally takes part in the formation of the lobes.

Fig. 348. — Mesodermal anlage of the lung of the embryo Chr. 1 (7 mm; compare Fig. 342). (After Narath, 1901.) Ven. p., pulmonary vein. The remaining lettering as in Fig. 342. X 100.

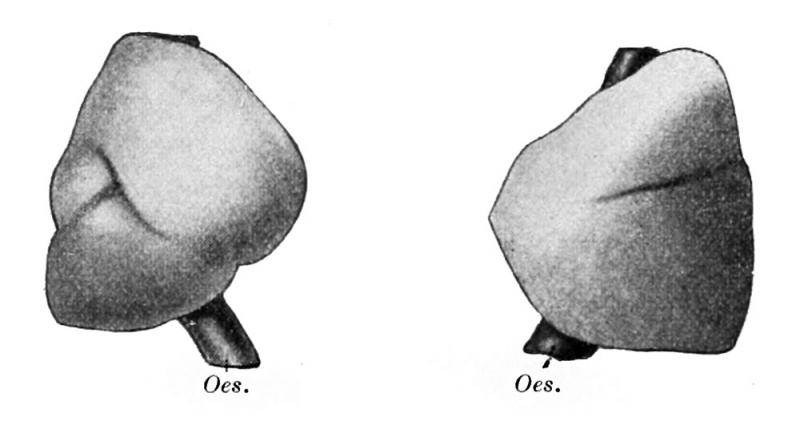

Figs. 349 and 350. — Mesodermal anlage of an embryo of about 13 mm. seen from the ventral and the dorsal surface. (After Blisnianskaja, 1904.) Oes., oesophagus. The remaining lettering (added by the present author) as in Fig. 342; in the right apical lobe (di) a subdivision into a dorsal and a ventral (d and v) portion is indicated. X 25. Fig. 349. | Fig. 350.

Figs. 351 and 352. — Lungs of an embryo of about 17.5 mm seen from the right and from the left. (After Blisnianskaja, 1904.) Oes., oesophagus. X 12. Fig. 351. | Fig. 352.

The arrangement of the lobes in animals and also a number of human variations, as well as the embryonic arrangement of the lobes, can be referred to a schema given by Narath (Fig. 353), in which the boundaries of the lung tiers (principal grooves) and those between the dorsal and ventral zones (accessory grooves) are shown as boundaries of the lobes. The most frequent variety is probably, however, the occurrence of a right infracardial lobe, which owes its existence to a similar process taking place on the medial surface and base of the lung. The lobes, as well as the bronchi, are, however, greatly reduced in man, in correspondence with the shortening of the trunk and the appoximation of the heart to the diaphragm (Ruge). As regards the corresponding pleural space see Vol. I, p. 547. The separation of a lobe from the right apex by the vena azygos is a variation that has nothing to do with the formation of the bronchial tree, but is rather to be explained as an adaptation of the lung to the space at its disposal (Narath, Bluntschli, 1905). The complete separation of portions of the lung, occasionally observed, is to be referred to disturbances in the early embryonic stages of development (Hammar, 1904).

To be seen in the upper lobe in Fig. 350.

Blisnianskaja has given some data regarding the evolution of the form of the lung as a whole. The form of the embryonic lungs is especially influenced by the great size of the heart; what are later the medial surfaces are first directed ventrally, and the lateral ones dorsally. The lungs are at first relatively more developed in what is later the dorsoventral (in the embryo approximately transverse) diameter than in the transverse (in the embryo almost sagittal) one, a condition that recalls what occurs in lower forms (apes). The same holds for the position of the base of the lung, which at first is much more sloped than it is later (compare Figs. 351 and 352). The lungs are drawn out almost to a point, which forms the lower and posterior pole. In the third fetal month they gradually assume the proportions seen in the adult.

Fig. 353. — Schema of the lobation of the lung. (After Narath, 1901.) D and V, dorsal and ventral lobes.

Text Notes

- ↑ A. Weber and his coworker Buvignier in several papers declare themselves in favor of a paired anlage for the mammals and for the homology of the lungs with the gills.

Literature

(The Normentafel referred to in the text is the Normentafel des Menschen, Jena, 1908, by Keibel and Elze.)

| Embryology - 28 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Grosser O. Lewis FT. and McMurrich JP. The Development of the Digestive Tract and of the Organs of Respiration. (1912) chapter 17, vol. 2, in Keibel F. and Mall FP. Manual of Human Embryology II. (1912) J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

A. Literature on the Development of the Pharynx

Bien, G. : Ueber accessorische Thymuslappen imj trigonum caroticum, Anat. Anz., vol xxix, 1906.

Bien, G. : Ueber accessorische Thymuslappen im trigonum caroticum bei einem Embryo von 17 mm. grosster Lange, Anat. Anz., vol. xxxi, 1907.

Born, G. : Ueber die Derivate der embryonalen Schlundbogen und Schlundspalten bei Saugetieren, Arch, fiir mikr. Anat., vol. xxii, 1883.

Dandy WE. A human embryo with seven pairs of somites measuring about 2 mm in length. (1910) Amer. J Anat. 10: 85-109.

Elze, C. : Beschreibung eines raenschlichen Embryo von ea. 7 mm. grosster Lange, etc., Anat. Hefte, vol. xxxv, 1907.

Erdheim, J.: I. Ueber Sebilddriisenaplasie. II. Geschwiilste des ductus thyreoglossus. III. Ueber einige menschliche Kiemenderivate. Beitr. zur path. Anat. und allg. Path., vol. xxxv, 1904.

Fox H. The pharyngeal pouches and their derivatives in the mammalia. (1908) Amer. J Anat. 8(3): 187-250.

Getzowa, S. : Ueber die glandula paratbyreoidea, intrathyreoidale Zellhaufen derselben und Reste des postbranchialen Korpers, Arch, fur path. Anat., vol. clxxxviii, 1907.

Greil, A. : 1905. See p. 496.

Groschupp, K. : Bemerkungen zu der vorlaufigen Mitteilung von Jacoby : Ueber die Entwicklung der Nebendrusen der Sehilddruse und der Carotidendriise, Anat. Anz., vol. xii, 1896.

Groschupp, K. : Ueber das Vorkommen eines Tbymussegmentes der vierten Kiementasche beim Menschen, Anat. Anz., vol. xvii, 1900.

Grosser, O. : Zur Kenntnis des ultimobrancbialen Korpers beim Menchen, Anat. Anz., vol. xxxvii, 1910.

Grosser, O. : Der Nerv des funften Visceralbogens beim Menschen, Anat. Anz., vol. xxxvii, 1910.

Grosser, O. : Zur Entwicklung des Vorderdarmes menscblicher Embryonen bis 5 mm. grosster Lange. Sitzber. R. Akad. Wiss. Wien, vol. cxx, 1911.

Gruenwald, L. : Ein Beitrag zur Entstehung und Bedeutung der Gaumenmandeln, Anat. Anz., vol. xxxvii, 1910.

Hammar, J. A.: Studien iiber die Entwicklung des Vorderdarmes und einiger angrenzender Organe. I. Abth. Allgemeine Morphologie der Schlundspalten beim Menschen. Entwicklung des Mittelohrraumes und des ausseren Gehorganges, Arch, fur mikr. Anat., vol. lix, 1902. — II. Abth. Das Schicksal der zweiten Schlundspalte. Zur vergleichenden Embryologie und Morphologie der Tonsille, Arch, fiir mikr. Anat, vol. Ixi, 1903.

Hammar, J. A. : Ein beachtenswerter Fall von kongenitaler Halskiemenfistel nebst einer Uebersicht iiber die in der normalen Ontogenese des Menschen existierenden Vorbedingungen solcber Missbildungen, Beitr. zur path. Anat. und allg. Path., vol. xxxvi, 1904.

Hammar, J. A.: Ueber die Natur der kleinen Thymuszellen, Arch, fiir Anat. u. Phys. Anat. Abth. 1907.

Hammar, J. A. : Fiinfzig Jahre Thymusf orschung. Kritische Uebersicht der normalen Morphologie, Ergebn. der Anat. u. Entwicklungsgesch., vol. xix, 1910.

Hammar, J. A.: Zur groberen Morphologie und Morphogenie der Menschen thymus. Anat. Hefte, vol. xliii, 1911.

Herrmann, G., and Verdun, P. : Notes sur l'anatomie des eorps post-branchiaux. Miseellanees biologiques dediees au professeur Alfred Giard. Paris 1899.

Herrmann, G., and Verdun, P. : Persistance des corps post-branchiaux chez l'homme. Remarques sur l'anatomie comparee des corps post-branchiaux. Comptes Rend. Soc. Biol. Paris, 1899.

Herrmann, G., and Verdun, P. : Note sur las corps post-branchiaux des Cameliens.— Les corps post-branchiaux et la thyroide; vestiges kystiques. Comptes Rend. Soc. Biol. Paris, 1900.

His, W. : Anatomie menschlicher Embryonen, Heft 3, Leipzig, 1885.

His, W. : 1. Ueber den sinus praecervicalis und iiber die Thymusanlage. 2. Nachtrag zu vorstehender Abhandlung. Arch, fiir Anat. u. Phys. Anat. Abth. 1886.

His, W. : Schlundspalten und Thymusanlage, Arch, fiir Anat. u. Phys. Anat. Abth. 1889.

Ingalls, N. W. : Beschreibung eines menschlichen Embryo von 4.9 mm. Lange, Areb. fiir mikr. Anat., vol. lxx, 1907.

Kastschenko, N. : Das Scbicksal der embryonalen Scblundspalten bei Saugetieren, Arcb. fiir mikr. Anat., vol. xxx, 1887.

Kohn, A.: Studien iiber die Scbilddriise, I and II, Arch, fiir mikr. Anat., vols. xliv and xlviii, 1895 and 1896.

Kohn, A.: Die Epithelkorperchen, Ergebn. der Anat. u. Entwicklungsgescb., vol. ix, 1899.

Kroemer: Wacbsmodell eines jimgen menschlichen Embryo, Verb. d. Deutsch. Ges. fiir Gynak., 1903.

Kuersteiner, W. : Die Epithelkorperchen des Menschen in ibrer Beziehung zur thyreoidea und thymus, Anat. Hefte, vol. xi, 1898.

Low A. Description of a human embryo of 13-14 mesodermic somites. (1908) J Anat Physiol. 42(3): 237-51. PMID 17232769 | PMC1289161

Mabesch, R. : Kongenitaler Defekt der Schilddriise bei einem elf jahrigen Madchen mit vorhandenen " Epitbelkorpercben," Zeit. fiir Heilk., vol. xix, 1898.

Maurer, F. : Die Schilddriise, thymus und andere Schlundspaltenderivate bei der Eidechse, Morph. Jahrb., vol. xxvii, 1899.

Maurer, F. : Die Entwicklung des Darmsystems, Hertwig's Handb. der vergl. u. exp. Entwicklungslehre, vol. ii, 1902.

Maximow, A. : Untersuchungen iiber Blut und Bindegewebe. II. Ueber die Histogenese der thymus bei Saugetieren, Arch, fiir mikr. Anat., vol. lxxiv, 1909.

Meyer, R. : Ueber Bildung des Recessus pharyngeus medius s. Bursa pharyngea im Zusammenhang mit der Chorda dorsalis bei menschlichen Embryonen. Anat. Anzeiger. Bd. 37. 1910.

Peuker, H. : Ueber einen neuen Fall von kongenitalem Defekt der Schilddruse mit vorhandenen " Epithelkorperchen," Zeitschr. f . Heilk., vol. xx, 1899.

Piersol, G. A. : Ueber die Entwicklung der embryonalen Scblundspalten und ihre Derivate bei Saugetieren, Zeit. fiir wiss. Zool., vol. xlvii, 1888.

Prenant, A. : Contribution a l'etude organique et histologique du thymus, de la glande thyroide et de la glande carotidienne, La Cellule, vol. x, 1894.

Prenant, A. : Sur le developpement des glandes accessoires de la glande thyroide et celui de la glande carotidienne, Anat. Anz., vol. xii, 1896.

Rabl, C. : Zur Bildungsgeschichte des Halses, Prager ined. Wochenschr., vols, xi and xii, 1886 and 1887.

Rabl, H. : Ueber die Anlage der ultimobranchialen Korper bei den Vogeln, Arch. fur mikr. Anat., vol. lxx, 1907.

Schaffer, J., and Rabl, H. : Das thyreothymische System des Maulwurfs und der Spitzmaus. I. Morphologie und Histologic by J. Schaffer. II. Die Entwicklung des thyreo-thymischen Systems beim Maulwurf by H. Rabl. Sitzber. kais. Akad. Wiss. Wien, vols. 117 and 118, 1908 and 1909.

Simon, Ch. : Thyroide laterale et glandule thyroidienne chez les mammif eres, Nancy, 1896.

Stteda, L. : Untersuchungen iiber die Entwicklung der glandula thymus, glandula thyreoidea und glandula carotica. Leipzig, 1881.

Stoehr, P. : Die Entwicklung des adenoiden Gewebes, der Zungenbalge und der Mandeln des Menschen, Festschr. z. fiinfzig jahrigen Doktorjubilaum von Nageli und Kolliker, 1891. (Author's abstract in Anat. Anz., vol. vi, 1891 1892.)

Stoehr, P. : Ueber die Natur der Thymuselemente, Anat. Hefte, vol. xxxi, 1906.

Stoehr, P. : Ueber die Abstammung der kleinen Thymusrindenzellen, Anat. Hefte, vol. xii, 1910.

Sudler MT. The development of the nose and of the pharynx and its derivatives in man. (1902) Amer. J Anat. 1:391–416.

Tandler, J. : Ueber die Entwicklung des V. Aorteubogens und der V. Schlundtasche beirn Menschen, Anat. Hefte, vol. xxxviii, 1909.

Tettenhamer, E. : Ueber das Vorkommen offener Seblundspalten bei einem mensch lieben Embryo, Miincbener med. Abhandl., Series 7, part 2, 1892.

Thompson P. Description of a human embryo of twenty-three paired somites. (1907) J Anat Physiol, 41(3):159-71. PMID 17232726

Thompson P. A note on the development of the septum transversum and the liver. (1908) J Anat Physiol. 42(2): 170-5. PMID 17232762

Tourneux, F., and Soulie, A.: Sur l'existence d'une V. et d'une VI. poche endodermique ehez l'embryon humain, Comptes Rendus Soe. Biol. Paris, .1907.

Tourneux, F., and Verdun, P. : Sur les premiers developpements de la thyroide, du thymus et des glandules thyroidiennes, Journ. de l'Anat. et de la Phys., vol. xxxiii, 1897.

Verdun, P. : Derives branchiaux chez les Vertebres superieurs, These, Toulouse, 1898.

Woeleler, A. : Ueber die Entwicklung und den Bau der Schilddruse mit Riicksicht auf die Entwicklung der Kropfe. Berlin, 1881.

Zuckere:andl, E. : Die Epithelkorperchen von Didelphys azara nebst Bemerkungen iiber die Epithelkorperchen des Menscben, Anat. Hefte, vol. xix, 1902.

Zuckerkandl, E. : Die Entwicklung der Schilddruse und der thymus bei der Ratte, Anat. Hefte, vol. xxi, 1903.

B. Literature on the Development of the Respiratory Tract

Aeby, C. : Der Bronchialbamn der Saugetiere und des Menscben, Leipzig, 1880.

Blisnianskaja, G. : Zur Entwicklungsgesehichte der menschlichen Lungen : Bronchialbaum, Lungenform, Dissert., Zurich, 1901.

Bluntschli, H. : Bemerkungen iiber einen abnormen Verlauf der vena azygos in einer den Oberlappen der rechten Lunge durchsetzenden Pleurafalte, Morph. Jahrb., vol. xxxiii, 1905.

Broman, J. : Die Entwicklungsgesckiehte der bursa omentalis, Wiesbaden, 1904. Fein, J.: Die Verklebungen im Bereiche des ernbryonalen Kehlkopfes, Arch, fiir Laryngol., vol. xv, 1903.

Flint JM. The development of the lungs. (1906) Amer. J Anat. 6: 1-137.

Frazer JE. Development of the larynx. (1910) J Anat. 44: 156-191. PMID 17232839

Goeppert, E. : Die Entwicklung des Mundes, etc., die Entwicklung der Schwimmblase, der Lunge und des Kehlkopfes der Wirbeltiere, Hex-twig's Handb. der vergl. und exp. Entwicklungslehre, vol. ii, 1902.

Greil, A.: Ueber die Anlage der Lungen, sowie der ultimobranchialen (postbranchialen, suprapericardialen) Korper bei anuren Amphibien, Anat. Hefte, vol. xxix, 1905.

Greil, A. : Bemerkungen zur Frage nach dem Ursprung der Lungen, Anat. Anz., vol. xxxvii, 1910. Grosser, O. : 1910 and 1911. See p. 491.

Hammar, J. A.: 1902. See p. 494. Hammar, J. A. : Ein Fall von Nebenlunge bei einem Menscben fetus von 11.7 mm. Nackenlange, Beitr. zur path. Anat. und allg. Path., vol. xxxvi, 1904.

d^Hardhtllier, A. D. : Developpement et homologation des bronches principales chez les mammiferes, Thesis, Nancy, 1897. His, W. : 1885. See p. 494.

His, W. : Zur Bildungsgeschiehte der Lungen beim menschlichen Embryo, Arch. fiir Anat. und Phys., Anat. Abth., 1887.

Kallius, E. : Beitrage zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des Kehlkopf es, Anat. Hef te, vol. ix, 1897.

Kallius, E.: Beitrage zur Entwicklung der Zunge. III. Teil: Siiugetiere. 1. Sus scrofa dom., Anat. Hefte, vol. xli, 1910.

Linser, P. : Ueber den Ban und die Entwicklung des elastiscken Gewebes in der Lunge, Anat. Hefte, vol. xiii, 1900.

Merkel, P. : Atmungsorgane, in Bardeleben's Handb. der Anat des Menschen, vol. vi, 1902.

Moser, F. : Beitrage zur vergleichenden Entwicklungsgeschichte der Wirbeltierlunge, Arcb. fiir mikr. Anat,, vol. lx, 1902.

Narath, A.: Der Broncbialbaum der Saugetiere und des Menschen, Bibliotbeca medica, Abtb. A., Anat., Pt. Ill, Stuttgart, 1901.

Pensa, A. : Considerazioni intorno alio sviluppo dell' albero broncbiale nell' Uomo e in Bos taurus. Boll. Soc. Med. Chir., Pavia, vol. xxiii, 1909.

Robinson, A. : Observations on tbe Earlier Stages in the Development of the Lungs of Rats and Mice, Journ. of Anat. and Phys., 1889.

Schmidt, V. : Zur Entwicklung des Kehlkopfes und der Luf trohre bei den Wirbeltieren, Anat. Anz., vol. xxxv, 1910.

Soulee, A., and Bardier, E. : Recherches sur le developpement du larynx chez l'homme, Journ. de l'Anat. et de la Phys., vol. xlii, 1907.

Thompson P. Description of a human embryo of twenty-three paired somites. (1907) J Anat Physiol, 41(3):159-71. PMID 17232726

Thompson P. A note on the development of the septum transversum and the liver. (1908) J Anat Physiol. 42(2): 170-5. PMID 17232762

Weber, A., and Buvtgnier, A. : L'origine des ebauches pulmonaires chez quelques vertebres superieurs, Bibliogr. Anat., vol. xii, 1903.

Figures

- “Respiratory

| Embryology - 28 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Grosser O. Lewis FT. and McMurrich JP. The Development of the Digestive Tract and of the Organs of Respiration. (1912) chapter 17, vol. 2, in Keibel F. and Mall FP. Manual of Human Embryology II. (1912) J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 28) Embryology Book - Manual of Human Embryology 17-10. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_Manual_of_Human_Embryology_17-10

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G