Paper - Development of the larynx (1910)

| Embryology - 26 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Frazer JE. Development of the larynx. (1910) J Anat. 44: 156-191. PMID 17232839

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Development of the Larynx

By J. Ernest Frazer, F.R.C.S.,

Senior Demonstrator in the Anatomical Department, King’s College.

Object and Material

The great work which Professor His carried out on early human embryos has made us well acquainted with the general arrangement of the parts in the floor of the pharynx, Since his time Hammar, Tourneux and Verdun, Kallius and others have also contributed much to our knowledge of this important region.

With regard, however, to the exact relations of the ventral ends of the arches to one another, and the precise mode of formation of the back part of the tongue and the development of the larynx, there is still need for further research. Besides certain gaps which exist in our knowledge of the successive stages of growth of these parts, there are, for example, marked differences of opinion on the involvement and fate of the ventral ends of the visceral arches.

The present investigation was therefore undertaken with the object of working out more particularly the ontogenetic development of the larynx in human embryos, and incidentally of tracing as far as possible the different stages of the development and growth of the parts forming the floor of the pharynx. ‘

For this purpose recourse has been had to the study of wax-plate reconstruction models and histological examination of longitudinal and transverse sections through the developing parts. The models which have been made show the embryonic pharynx and larynx in specimens of the following sizes :—

| I. 5 mm. x 50. | V. 12 mm. x 50. |

| II. 6.6 mm.x 50. | VI. 16 mm. x 50. |

| III. 7 mm. x100. | VII. 22 mm. x 33. |

| IV. 8.5 mm. x 50. | VIII. 35 mm. x 25. |

There are, in addition, models of the laryngeal cavities in 35 mm. x 33, and in 5 mm. x 100 and some separate cartilages from an embryo of 32 mm. x 25 ; also two models from young pigs.

A model of the pharynx of an embryo of 3 mm. was not completed, as the specimen was not in a state of good preservation, and a reconstruction of the external aspect of the pharynx of a 2.5 mm. embryo is shown in its place: this was made a few years ago by Professor Peter Thompson, and I take this opportunity of expressing my most sincere thanks to him, to Professor Arthur Robinson, and to Dr G. J. Jenkins for their kindness in freely putting at my disposal such of their material as was suitable for my purpose.

The histological material included, in addition to the sections from which the reconstructions were made, specimens of 18 mm., 32 mm., and over; observations were also made on embryos of pig, rabbit, and frog.

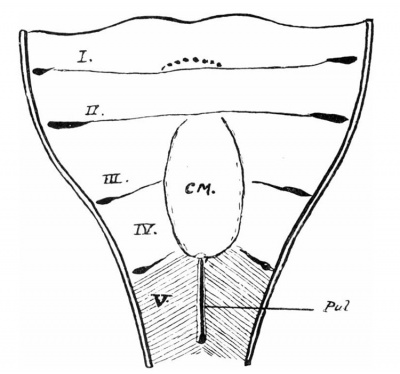

FIG. 1. Reconstruction model : embryo 5 mm.

The models, with the exception of IV., are coloured, and in the older ones the colouring is designed to show cartilage, precartilaginous tissue, mesenchymal thickenings, and undifferentiated tissue.

Before dealing as a whole with the question of the development of the larynx, a short description of some of the main characters of these models, in so far as they bear on the present subject, may be of value.

I. (5 mm., fig. 1). — The four arches are distinct with their intervening clefts; the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th clefts deepen at the sides into pouches. A minute tuberculum impar is showing. The 2nd arch is clear in the middle line, but behind this there is a. longitudinally placed central mass into which the 3rd and 4th arches run.

The sagittally placed laryngeal fissure lies behind the level of the 4th pouches, and at each side of it the floor is raised up into rounded swellings.

- I use lines drawn between corresponding pouches as convenient levels for descriptive purposes, but it must not be forgotten that, owing to the increasing obliquity of the arches, the statement that a structure is above any pouch-level does not necessarily mean that it is in the region of the corresponding arch.

The whole general cavity narrows fairly gradually from the 2nd cleft to behind the situation of the fissure.

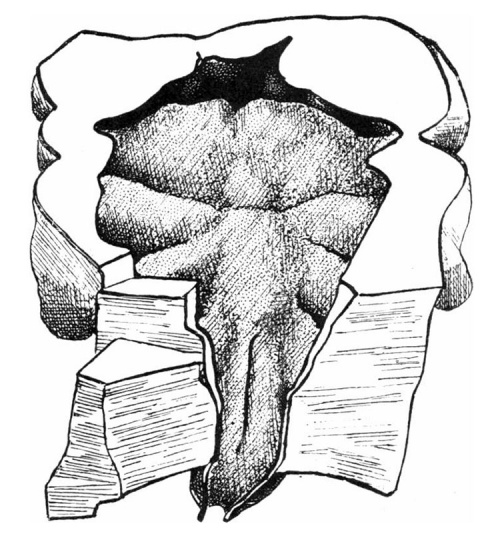

II. (6 mm., fig. 2). — Tl1e ventral fusion of the 3rd and 4th arches is a prominent mass, standing out well above the levels at each side and receiving the 2nd arches in front. The cavity narrows rapidly over the 3rd arch, but behind the 3rd cleft it more gradually decreases to the level of the hinder end of the fissure. The masses bounding the fissure reach

Fig. 2. Reconstruction model : embryo 6 mm.

with it the level of the top of the 4th pouches; the walls of the fissure are closely pressed together—showing as a groove in the model—so that no opening is apparent, save at the lower end, where a patent track leads into the “trachea.”

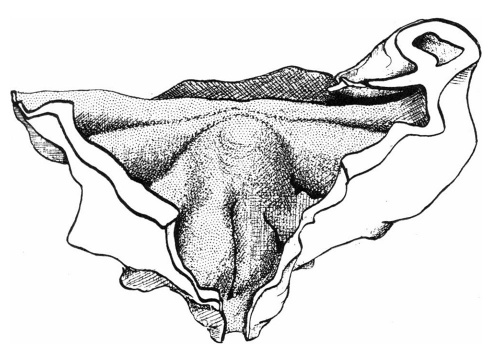

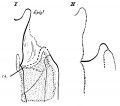

III. (7 mm., fig. 3).—The model is not completed in the region of the 1st arch. The pouches are Very evident. The central mass is marked, and seems to correspond mainly with ventral ends of 4th arches, with the attenuated ends of the 3rd arches running into its front part.

The fissure with its bounding masses ends in part on the base of the median prominence, well above the level of the 4th pouches; the masses are well marked, bulky, and prominent, and at their lower ends—between which there is an opening into the tracl1ea—the general cavity narrows suddenly. The cavity gives the impression of being somewhat widened by the enlargement of the masses, being otherwise like that in the last model.

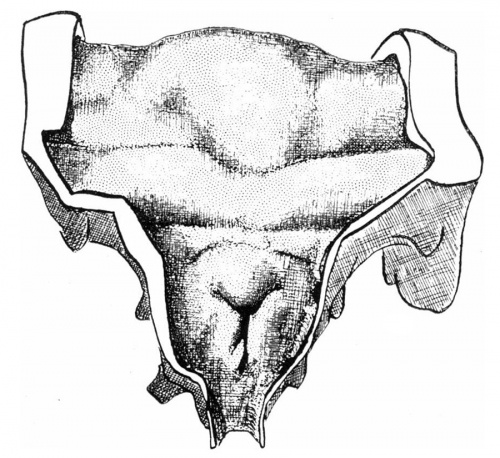

IV. (8.5 1nm., fig. 4). Pouches are still discernible. The cavity narrows rapidly along the 3rd arches, but very slightly behind these, till it reaches the level of the lower opening in the fissure.

The middle mass is prominent, and seems to contain more 3rd arch element than in the preceding specimens. The two lateral masses seem to have extended forward, diverging to lie on each side of the central swelling, which is thus exposed between their upper extremities; these fuse with the lateral aspect of the central mass, about half way». between the levels of the 2nd and 3rd pouches. Behind these extremities, the lateral masses enlarge, overlapping the base of the median eminence, and meet in the middle line about half way between the 3rd and 4th pouchlevels. Below this they form the lips of the fissure, which terminates in a small free opening just below the level of the 4th pouches.

Fig. 3. Reconstruction model : embryo 7.5 mm. First arch incomplete.

Owing to this disposition of the lateral masses, the line of the opening into the future laryngeal cavity can be described as Y-shaped, the limbs of the Y having between them the lower part of the median prominence, on which a short, slightly marked groove is seen, representing the upper termination of the original fissure.

V. (12 mm., fig. 5).—The lateral pouches are only just discernible. The general cavity narrows rapidly internal to and behind the 2nd pouch, the side wall passing almost directly inwards, but over the middle of the 3rd arch the line of the wall passes more directly backwards with a slight inclination inwards, past the 3rd and 4th pouches, to narrow again rapidly below this.

The arches are distinguishable, the 3rd small and apparently running into the front part only of the mesial mass. Behind this the laryngeal surface swellings stand altogether above the level of the 4th pouches, the lateral masses being smooth and prominent, and much thicker than in the preceding model: their upper ends are broad and thick, and seem to be continuous with the sides of the upper part of the central mass, above the level of the 3rd pouches. The central mass is rounded and broader for its height than in the previous Inodel, so that the limits of the Y—shaped opening are more divergent.

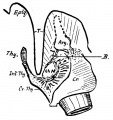

Fig. 4. A. Reconstruction model : embryo 85 mm. B. Surface view of laryngeal opening of same seen somewhat from the side, showing the lateral masses commencing to overlap the central mass : the 3rd and 4th pouches are seen at the side.

VI. (16 mm., fig. 6).—There are no indications of separate arches or clefts, save the lower ends of the Eustachian pouches. The epiglottis is distinct, separated by a sulcus from the back of the growing tongue. The lateral masses are much more prominent, particularly in the neighbourhood of the hinder end of the sagittal fissure, so that this is lifted up into a line directed more dorso—ventrally than before. The laryngeal surface area has increased in breadth but not in length, so that the transverse part of the fissure makes a T-shape instead of a-Y.

The growth of the lateral masses has increased the extent of the laryngeal cavity, but in its greater part the side walls are still pressed together and adherent: the transverse part is open for the most part, and an imperfectly open channel runs down to the trachea in the dorsal part of the cavity.

Fig. 5. Reconstruction model : embryo 12 mm.

VII. (22 mm., fig. 7).— The surface appearances here are much the same as in the last model, save that the outer parts of the lateral masses are more prominent.

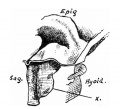

VIII. (35 mm., fig. 8).— The lateral swellings do not till the cavity of the pharynx, but are 1nucl1 slightcr, thinning upwards to their apices ; these are separated from the epiglottis by a transverse fissure with the points of the limbs turned back, continuous in the middle line with the open sagittal cleft. The latter has come down from its somewhat dorso-ventral direction nearly to its original plane. The cavity is open nearly throughout. The tops of the lateral swellings are at a lower level than iii the last two models, judging from their relation to the position of the thyo—hyoid junction. Epiglottis is not a transverse bar, but a thick median upstanding prominence.

Fig. 6. (16 mm).

A is a view from behind of the model. about half size, with part of the floor removed below.

B is a side view of the crieoid and arytaanoid rudiments lying against the lining of the segittal cavity: the transverse cavity is seen in front of the arytaenoid. The epiglottic ridge is seen above and in front, and behind this is the lateral mass separated from it by the depression of the transverse opening.

C. Median section through “cavity.” The greater part of the area of the sagittal wall is adherent, leaving only channels along the dorsal wall and floor. The “ ventral lamina. ” (V.L.) is seen below the‘floor, as in the previous figure.

D. The form of the hyoid and thyroid : the lesser cornu is continuous with its fellow in the upper part of the “ body.”

The larynx is outlined deeply. Chondrification seems most advanced in the dorsal aspect of the body, where there is a. single median nodule that is plainly cartilaginous. The rest of the structure shows only precartila.ginous states in various places.

Fig. 7. (22 mm).

B is a side view of the deeper structures in A after removal of the loose piece. The lighter portion of the cricoid and arytaenoid exhibit cartilaginous change, more advanced in the former. The chordal nodule is seen below and in front of the Arytenoid, and, in front of this, the lateral edge of the wall of the transverse cavity passes upwards and outwards.

C is an outline of the thyroid ala. and its continuity with the greater cornu.

D gives the outline of the hyoid, thyroid, and inter-thyroid lamina, and cricoid from the front.

The numerous remaining structures in the last three models, with the other points that are evident in the earlier ones, will be described as they come into the account of the growth of the larynx.

A short general consideration of the floor of the pharynx can conveniently precede the description of the laryngeal development, with the object of showing that five arches are represented in this floor.

Fig. 8. (35 mm. ).

A is a reduced drawing of the model from behind.

B is a larger drawing of the model from the left and below, the lateral piece being removed with the thyroid ala. The chordal nodule (Ch. N.) is seen connected below with the cricoid, which is very large. The saccular outgrowth (S¢wc.) has the false cord above it, and, above this, the lateral edge of the wall of the transverse cavity is seen. Part of the wall of the sagittal cavity is shown (s) behind the arytaenoid, and a little of this wall is exposed behind and below the chordal nodule, where the original connection of the nodule with the cricoid has thinned out, and is no longer demonstrable, leaving the wall exposed.

C. A drawing of a separate model of the cavity oi the same embryo, divided mesially and seen from the right.

General Consideratlon of the Floor of the Pharynx

The floor of the human pharynx is formed by hypoblast covering the ventral ends and ventro-lateral parts of the visceral arches. These arches differentiate from before backwards, so that in the third week the 1st and 2nd are easily distinguishable, the 3rd is indicated laterally, while the 4th cannot be distinguished a lateral swelling, although its future position is made. manifest by the development of a fourth recess a very short distance behind the third recess.

Each arch is formed of a bar of mesoblast, which seems to grow ventrally and inwards, lifting up the lining of the floor as it extends; it has a corresponding nerve, following the growth in point of time, and in its extension seems to follow the line of a corresponding vessel running ventro-dorsally from the common aortic stem. Possibly as a result of this, the general direction of the various arches is towards a ventral central point, situated in the neighbourhood of the ventral ends of the 2nd or 2nd and 3rd arches; thus the ventral ends of the 1st arch tend a little backwards, and the 3rd and 4th tend forwards, the obliquity increasing from before backwards and with the increase in length of the pharynx.

Or the matter may be put in another way, by saying that the tendency of the arches is to run towards the hyoid complex, without considering the reason for the existence of this complex.

Before the arches meet ventrally, the wall of the pharynx in this situation is smooth and flat, but, by the time that they approach the middle line, a mesial longitudinal thickening has taken place there, and they run into this; at least, the 2nd, 3rd, a11d 4th arches end at first in this way, but the 1st arch, if it ever does so, is very quickly separated from the median part, and this becomes non-existent here, unless the small tuberculum impar can be considered to represent its remnant.

The arches become clear across the middle line; in other words, their ventral ends assert themselves and meet, cutting up the longitudinal mesial eminence into corresponding tralisversely-disposed portions, and this process proceeds, like the differentiation of the arches themselves, from before backwards.

Thus the 2nd arch is a continuous bar across the middle line some little time before the 3rd becomes clearly differentiated on the floor; but the 4th has undergone superficial changes of aspect so marked by this time, that its continuity across the middle line through the hinder part of the original longitudinal prominence can only he surmised from a surface examination of the pharyngeal floor.

The appearance of the arches ill the floor has a corresponding arrangement of cell-masses. Each arch is a prominence caused by a condensation of cells, that is continuous round the side of the pharynx, between the cleftrecesses, with a thin cell stratum placed on the dorso—lateral part of the roof, between it and the dorsal artery; the whole arch system is easily distinguished dorsally, laterally, and ventro—laterally from those in front of it and behind it, in sagittal and coronal sections during the fourth week. Where the central longitudinal eminence receives the arches, the cell-condensation is lost, and the eminence might be considered as a swollen ventral end joined with a similarly affected one; but the fact that the condensed bar of mesenchyme gets smaller an(l shallower as it approaches the possible central fusion would suggest rather that the latter is an independent central formation which has not yet been invaded by the growing arches. Such a formation might possibly have some connection with the presence of the underlying arterial axis.

Be this as it may, the surface extension of the clear arch to the middle line is accompanied by a corresponding extension of the condensed mesenchyme. So far as I have been able to follow the process, there seems first of all to be a deep prolongation of the arch structure, possibly in connection with the arterial course, and a later superficial extension under the hypoblast, gradually invading the central eminence from its outer side. In this way the 2nd and 3rd arches become clearly represented iii the floor of the pharynx, but I have not been able to satisfy myself as to the ultimate relation of the 4th arch to the remaining hinder end of the original central prominence. Possibly the arch may invade the prominence, as in the case of the anterior arches, but, if so, the fact is not so clear as in these; wherefore, leaving the question undecided, it will be convenient for the purpose of this paper to term this median hinder end simply the “central mass,” while the undoubted 4-th arch that runs into it and lies posterolateral to it can be spoken of as the “ ventro—lateral ” 4th arch.

The region of the pharyngeal floor that lies behind the 4th arches, and between them as they become obliquely placed during growth, would thus properly belong to a 5th arch area, and I hope to show that it should be so regarded: each 5th arch causes a swelling on the floor, and reaches the posterior end of the central eminence, and the pulmonary diverticulum opens into the pharynx between them.

The pulmonary outgrowth takes place in the third week, when the 4th arches are not as yet apparent, and it lies behind a bend in the smooth floor of the foregut. When the central longitudinal prominence is formed, this lies in front of the opening of the outgrowth, as do also the 4th arches running into this prominence, and behind these the 5th arches lie on either side of the opening: by this time the pulmonary outgrowth has increased in length, so that it is only its pharyngeal end that is held, as it were, between the 5th arches that lie in the floor of the pharynx on each side of it. The proximal part of the outgrowth thus included between the 5th arches becomes the lower part of the cavity of the larynx; the remaining upper part of the cavity is added to this secondarily.

The reasons that lead me to think that the bars which lie on each side of the opening of the outgrowth are of the nature of 5th arches, do not only consider the position and surface appearances and relations, b11t also take into account the result of examinations of sections histologically.

The condensed mesenchyme that forms the basis of this “ arch ” is very marked in its character, and very distinct in its limits in the 5 mm. embryo —more so tha11 is the case in the other arches. In a 3 mm. specimen the condensation also seemed slightly more marked than in the other arches, but the cells in these earlier floors are on the whole more loosely aggregated, and the limits of the arches can only be fixed by the situation of the clefts.

5 mm. sagittal sections show the very definite front limit of the condensation in question, and transverse sections show its lateral extent, which is also well defined.

This mass lies beside the pharyngeal end of the pulmonary outgrowth, which it and its fellow compress between them, so making the walls meet and adhere, and converting this pharyngeal or cephalic end of the outgrowth into a sagittal (potential) cleft. The mass is continued forwards as far as the cleft extends, getting smaller as it does so, so that it has an irregular wedge shape; the thick base behind is continuous with a marked condensation that lies lateral to the pharynx a little distance behind the 4th pouch, a11d this in its turn is continued on to the dorso-lateral wall of the pl1arynx—or what might perhaps be now termed the (esophagus.

In later embryos the increasing obliquity of the posterior arches in the floor leads to elongation of the Wedge-like portion of this condensation that lies beside the cleft, so that, still bounding the cleft, it lies between it and the 4th arch, which is placed antero-lateral to it, and narrows to its apex, which reaches the base of the “central mass.”

An artery runs ventro-dorsally behind the 4th pouch, embedded in the front part of the lateral portion of the cell condensation, from the ventral aortic stem to the dorsal aorta: this is evidently i11 series with the aortic arches in the anterior condensations, as is distinctly seen in reconstructions or in longitudinal sections (see fig. 9).

A nerve accompanies the base of the wedge behind the 4th pouch, and, later, is found running forward with the drawn-out condensation.

It would seem, then, that this region agrees with those that are placed in front of it in the positive character of a mesenchymal condensation that is continued from the floor to the dorso-lateral part of the pharynx, and is distinct in its whole extent from the neighbouring arch, lies behind a definite visceral pouch or cleft, causes a ventral prominence in the floor, and is accompanied by an artery and nerve evidently in series with those lying in front of it. In addition, it may be pointed out that the condensation, laterally and dorso-laterally, lies between the pharynx and the main arterial plane, as in the other arches; and, as in them, there seems an early extension of the cell-thickening ventrally along the artery towards the aortic stem.

The apparent objections to the conclusion are only negative : there is no external manifestation of the arch, and there is no 5th pouch limiting it behind.

The first of these objections is of little importance, when one considers how slightly the 3rd arch shows, and the 4th still more slightly, and behind this comes a much thicker mass of tissue covering a much smaller pharynx, with the addition of large veins, pericardial structures, a11d commencing limb—bud.

The second objection does not seem of much weight, even if true; the rapidly elongating (esophageal region would tend to obliterate any sulcus that did not enlarge to form secondary bodies, and thus the chance of hitting upon the pouch—if it exists—would be rather small.

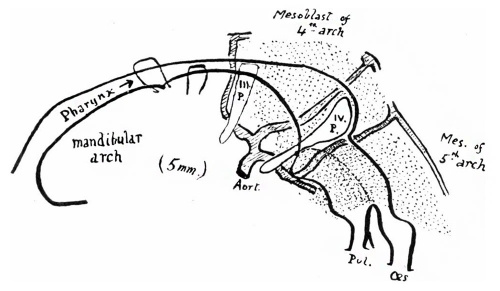

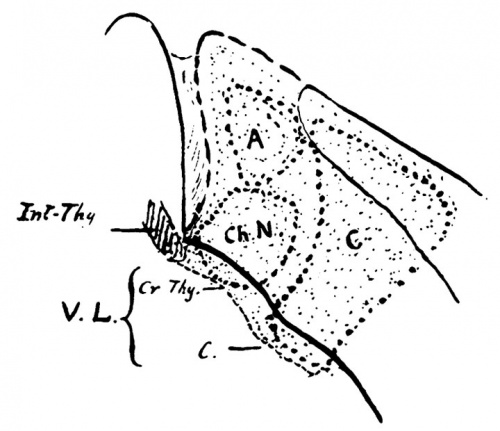

Fig. 9. 5 mm. embryo: graphic reconstruction showing the relation of the cell-masses of the 4th and 5th arches to each other and to the 4th pouch, situated between them. The relations of the pharyngeal wall as a whole are also indicated, and the position of the ventrolateral part of the 5th arch mass that forms the lateral wall of the laryngeal fissure is shown, behind the 4th pouch in this stage. The arteries of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th arches are represented running from the ventral aortic stem (Aort.) to the dorsal aorta.

Even if the pouch has no existence, its absence would not, in my opinion, invalidate in any way the positive claims of the structures described to be considered as of the nature of a visceral arch.

For these reasons it seems to 1ne that the floor of the human pharynx should be described as made up of the lower ends of five arches, tending to meet their fellows across the middle line—Wl1ere they are at first separated by a central longitudinal bar—and, as the pharynx grows, the posterior arches become obliquely placed in the floor; the opening of the air-tube is situated between the two 5th arches behind, as a sagittal cleft, and its bordering 5th arches are connected with each other by a ventral cellular bridge below it, and also by their apices at its anterior end, on the base of the central mass.

The condensations are also continuous with each other behind the situation of the fissure, by means of a bar of mesenchyme that lies under the floor of the pharynx immediately posterior to the fissured opening, and separates the pharynx from the underlying air-tube; it can therefore be stated that the hinder part of the 5th arch masses makes a continuous ring round the pulmonary out-growth in this situation.

When the air-tube elongates, and the “lateral masses ”—as will be described later——grow forward, this surrounding ring‘ is elongated with the tube it contains, and which is compressed at first by it into a narrow chink.

The question of the possibility of a 6th arch element existing in the floor has also been considered, but it does not seem possible to affirm or deny its existence from examination of the specimens.

Endeavouring, with an open mind, to follow the histological structure in both directions in all the younger specimens, I do not think one would be justified in saying more than this: that if there is a 6th element coming in, it appears to be lost in the deep posterior part of what I have termed the 5th arch mass. In trying, therefore, to keep the complicated description as clear as possible, I intend, with this reservation in mind, to term the whole condensation that has to do with the sagittal cleft the “ 5th arch,” for 1 do not think there can be any doubt that it is of this nature, so far as the greater part of its substance is concerned.

The Development of the Larynx

Although the various parts of the larynx are inter—dependent in their development, nevertlieless it would perhaps make clearer the account of the processes if the description were undertaken under different headings. l propose, therefore, to divide the subject into (a) the development of the cavity and true vocal cords, and (b) the development of the reniaining structures.

(A) The Cavity and True Vocal Cord

Under this heading I hope to show that the cavity of the adult larynx is composed of two parts, arising in dil'Yerent ways: if a. line is drawn backward along‘ the true vocal cords to the aryt:enoid, and then upwards along the front border of the arytaenoid prominence to its apex, that part of the cavity which lies below and behind this line is derived directly from the median sagittal cleft that lies below the floor of the pharynx, whereas the portion that lies above and in front of the line is formed secondarily, and its cavity is at first transverse in long direction and is really an included part of the pharynx.

In the third week and first part of the fourth week the anterior end of the pulmonary outgrowth is situated below the floor of the pharynx and compressed by the 5th arches, which lie on each side of it, so that it is only a potential cleft-—the sides being adherent in nearly their whole extent——and its pharyngeal opening is a mesial longitudinal fissure in the floor between the slight prominence of the 5th arches. This fissure, with its bounding arches, lies at first behind the level of the 4th pouches and reaches in front to the base of the central mass.

|

|

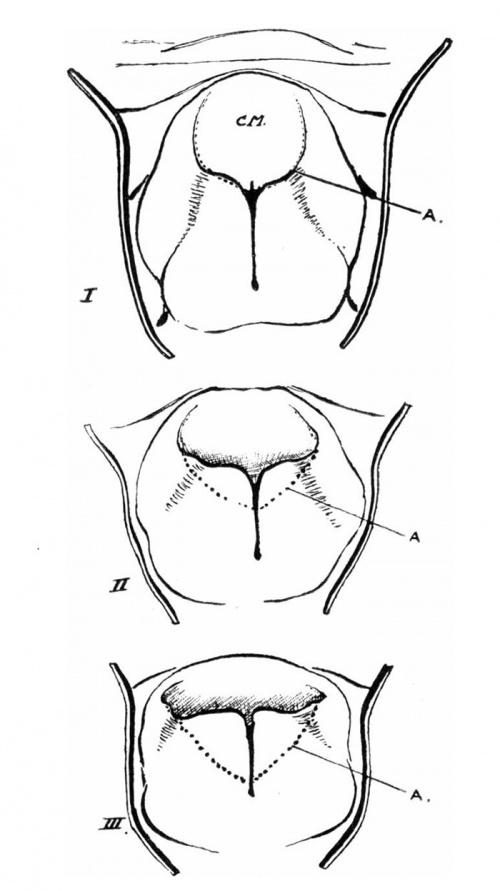

| Fig. 10. shows the position of the pulmonary opening (Pul.) behind the 4th pouch level: the 5th arch is obliquely shaded. The central mass (C.M.) is shown interposed between the ends of the 3rd and 4th arches. | Fig. 11. The diagram shows the increased obliquity of the hinder arches : the pulmonary opening is thus apparently in front of its position in the lust figure. The interrupted line B shows the outline of the lateral mass, which thus comprises 4th and 5th arches, and the thick line A indicates the line at which it begins to overlap the central mass; this line is seen to correspond with the margin of the central mass. |

The front end of the pulmonary opening is on the base of the central mass, bordered by the “ original apices ” of the 5th arches, and the line of overlapping therefore crosses the sagittal cleft at the point X; therefore, when overlapping occurs, the sagittal line in front of X is left on the base of the central mass with the original apex on each side of it, and a new dorsal apex of the 5th arch is lifted over the central mass, being originally behind and outside X.

The 4th arch element of the lateral mass is seen spreading up the side of C. M. and being lost there, and the 3rd arch is clear across the middle line.

The continuity between the two “ apices” of each 5th arch mass must lie under the sulcus formed at the line A where the shading crosses it.

The position of the opening and the arches at this stage is seen in the diagram in fig. 10.

As growth proceeds, the fissure gradually comes to occupy a higher position with reference to the 4th pouches, and the prominence of the 5th arches becomes more marked, so that, by the end of the fourth week, the 4th pouch level crosses the fissure about half way down its length, and the front end of the swollen 5th arches are lost, beside the anterior extremity of the fissure, on the base of the central mass a little below the level of the 3rd pouches.

The position at this stage is seen in fig. 11, where, in consequence of the apparent forward dislocation of the area, the 5th arches are now seen to have the 4th arches as antero—lateral relations.

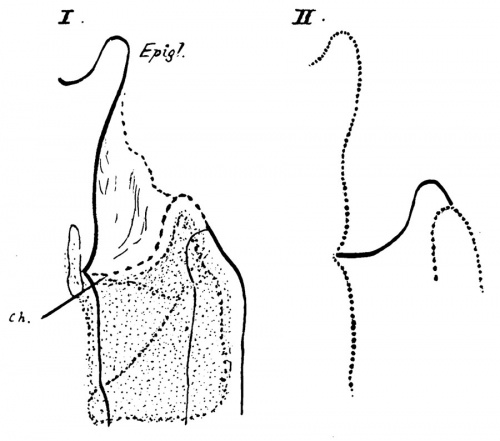

Fig. 12. (a) Diagrams of the mode of formation of the cavity, shown by sagittal sections in the middle line. The central mass (C.M.) is shown in outline, becoming the epiglottis, and the dotted area represents the 5th arch mass: the interrupted line that bounds this above corresponds with the margin of the sagittal opening in the pharyngeal floor. The second and third figures show the result of the overlapping of the central by the lateral mass, thus forming the transverse cavity (T) continuous with the original sagittal cavity (S) round the margin of the latter. The 4th arch element is seen forming the outer part of the dorsal wall of the trans verse cavity. The increase in size of the hinder part (V) of the 5th arch seems to be largely responsible for the lifting forward of the front part. V. L. is the “ ventral lamina” that connects the two 5th arch masses under the floor of the sagittal cavity. The angle of junction between the floors of the two parts of the whole cavity is seen to be well marked. (b) The lower figures illustrate the change in the direction of the line of the original sagittal opening, which is shown as a. thick line, in the various stages of its alteration.

Measurements on the models show that the fissure remains approximately of the same length, whereas the lateral walls of the pharynx increase in length, so that the forward movement is only an apparent one, due to want of growth (in length) of the floor, while the remainder of the general cavity grows with the embryo. While this is going on, the pulmonary outgrowth is increasing in length, ending behind in the lung buds; the drawing out of this tube, with the increasing obliquity of the hinder arches, leads to a proportionate stretching out of that part that is compressed by the deeper and hinder parts of the 5th arches, so that the sagittal “cavity” increases in length, although its “opening” remains stationary in size in the floor of the pharynx.

The result of these factors on the shape of the sagittal cleft is shown in the first diagram in fig. 12; the section is supposed to open up the cleft, and shows its bounding 5th arch mass running with it on to the base of tlie central mass, and becoming continuous, round its ventral side and end, with its fellow.

At this stage—i.e. at the and of the first or bcginoimg of second month —tl1e transverse part of the cavity begins to be formed by the active forward overlapping of the central mass by the 5th and 4th arches.

In the diagram (fig. 11) on the left side the vcntro-lateral 4th arch is seen lying outside and in front of the 5th arch, and extending up along the side of the central mass, running into it near the top; the 5th arches, as already shown, pass on to the central mass behind with the front end of the fissure between them.

The contiguous arches now begin to grow up together as a common “lateral mass " on each side, overlapping the central mass from behind and the side, at the line ofits margin, where they form a sulcus that rapidly deepens as they grow forward; the two sulci thus formed diverge in a Y—shape from the central fissure, the central mass being between the limbs of the Y.

Thus the front end of the 5th arch can be said to give a forward prolongation which forms the inner part of the (lo;-.s-al, wall of the sulcus, and is continuous round the hinder end of the floor of this sulcus with its original apex which lies ventrad to the sulcus, beside the anterior end of the original fissure; the outer part of the overlapping mass is composed of ventro-lateral 4th arch, and this extends up the side of the central mass, where its overlapping is gradually lost. The line along which this overgrowth of the conjoined arches begins to overlap the central mass is shown on the right side in the diagram (fig. 11) and corresponds with the margin of the central mass: the area of the “lateral mass” thus formed is also indicated in the diagram.

The original sagittal fissure extended on to the central mass, so that the line of the margin of the mass cuts across it at a point a little distance behind its front end; as the overlapping takes place along this margin, it follows that the diverging sulci thus formed open into the sagittal “cavity ” at this point, and the front end of the fissure is left on the central mass, which is going to form the ventral wall of the transverse cavity.

The formation of the sulcus seen from the middle line is shown in the second diagram in fig. 12; the surface view of the condition is seen in the model IV. (fig. 4), where the anterior end of the original groove is also apparent. The lateral masses, formed in this way by the two arches on each side, continue their forward growth as the dorsal walls of the sulci, which are thus converted into a. definite cavity directed transversely, narrowing from above downwards. Fig. 12 shows the alteration in the shape and build of the cavity due to the growth forward of the dorsal wall of each sulcus; the 5th arch or inner element in this lateral mass grows a little more rapidly than the outer 4th arch portion, so that the two parts are more on a level at the end of the process, as shown in fig. 13.

Fig. 13. To show the way in which the lateral masses overlap the central mass (C.M.) at the line A, and the inner or 5th arch element comes up more on a level with the 4th arch part. The early Y-shaped opening is converted into a. T-shape by this and by the increasing breadth of the central mass becoming the epiglottis, and the part of the 4th arch that runs up the side of the central mass is modified into the ary-epiglottic fold.

At the same time the central mass increases more in breadth than in height, and in this way the original Y-shape of the opening is widened out, showing more the form of a T, or of a Y with the limbs widely divergent and turned somewhat back at their extremities.

A transverse section through this part of the whole larynx would now give an outline to the cavity which is shown as a solid diagram in fig. 14; the transverse cavity is bounded in front by the central mass (now becoming more definitely an epiglottis) and is continuous with the sagittal cleft between the two lateral masses, which fit into the angles formed by the junction of the limbs and central stem of the T-shaped cavity, and thus form the two parts of its dorsal wall.

Fig. 14.

If this account has been followed, it is apparent that, whereas the dorsal and posterior part of the whole cavity is formed directly from the original sagittal cleft, the ventral and anterior transverse part is a secondary thing, due to the overlapping of the central mass by the forward growth of the lateral masses to form its dorsal wall ; that the opening of the transverse part into the pharynx is bounded laterally by the continuity of the outer and front extremity of the lateral mass (4th arch) with the central mass (epiglottis); that the lateral masses are made up of 5th and 4th arch element, and that the former is continuous with its original apex on the base of the central mass (the ventral floor of the transverse cavity) by a cell-continuity passing round the point of junction of the original sulcus with the original sagittal cleft.

The continuity just noticed between the primitive ventral and secondary dorsal parts of the 5th arch would thus lie beside the lowest part of the transverse cavity—in fact, at its junction here with the sagittal part; and the true vocal cord will be shown later to be developed in this line.

An angle is formed in the floor of the cavity at the junction of the transverse and sagittal parts i.e., at the posterior margin of the central mass (fig. 12). This angle persists markedly till late, till the growth of the cartilages straightens out the cavity, and can be found very slightly marked in sections of the adult larynx.

The overlapping of the lateral masses seems to be due more to an increase in their posterior parts than to growth elsewhere; this pushes the front parts forward, folding them over the margin of the central mass, as it were, and the excessive increase is more largely developed in the 5th arch elements. Resulting from this, two effects can be noticed here: the 5th arch dorsal parts are brought up nearly to a level with the 4th arch portions, and the original sagittal opening is lifted forward with these, leaving a 5th arch mass in the floor of the pharynx behind it.

Another result of the growth of the hinder part of the 5th arch element is that the line of the opening is “swung up” on its front end, becoming more dorso-ventral in direction than at first, and bent into an angle corresponding with the fore-part of the dorsal growth of the 5th arch element.

These details are illustrated in fig. 12.

What I have spoken of in this account as the lateral mass evidently corresponds with Kallius’ arytaenoidwiilste, and the prominent dorsal points of its 5th and 4th arch elements seem to represent his cornicular and cuneiform swellings; on this point of view, the shallow groove that separates them and runs outwards and backwards over the mass, towards the 4th pouch, would be serially homologous with the grooves between the arches in the remainder of the pharyngeal floor (fig. 13).

The true vocal cords are developed in connection with the bridge of continuity that exists between the ventral and dorsal parts of each 5th arch: they would thus correspond with parts of the original “free” margins of the arches that formed the edges of the sagittal fissure.

Their mode of formation is as follows :—

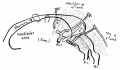

When the lateral masses have grown up to form the dorsal wall of the, transverse cavity, the dorsal part of each 5th arch lies in its corresponding mass in close contact with the lining of the sagittal cleft, and is continuous behind with the main body of the mass enclosing the proximal end of the drawn-out air tube; ventrally and in front it is directly continuous, as already shown, with the original apex of the arch on the base of the central mass, i.e., at the lowest part of the ventral wall of the transverse cavity. The whole 5th arch area thus defined is shown in figs. 12 and 15, and the two arches are connected with each other by a “ ventral lamina” passing under the floor of the (sagittal) cavity.

The arytaenoid and cricoid cartilages develop in this cell-condensation, as shown in fig. 15, and the two halves of the latter cartilage meet in the ventral lamina.

The “ventral lamina” immediately in front of this forms the central part of the crico—thyroid membrane, and this in its turn is continued into the lower part of the “inter—thyroid lamina,” a thick cell-layer that is interposed between the two halves of the thyroid cartilage.

It is apparent that, from this relationship, the crico—thyroid membrane (ventral part) and the lowest part of the inter—tl1yroid lamina must be connected with the cricoid behind, and, in front of this, with the more anterior parts of the 5th arches laterally.

The cell area in the angle between the arytaenoids and cricoid development (fig. 15) undergoes a condensation (ChN), and in the sixth week is almost in a precartilaginous condition. This “chordal nodule,” from its position and formation, is continuous dorsally with the arytaenoid anlage, behind, dorsally and ventrally with that of the cricoid, and ventrally with the ventral lamina forming the central crico-thyroid membrane and lower end of the inter—thyroid lamina.

Fig. 15. A continuation of Fig. 12. Shows the dotted area of thei lateral mass, with the relative position of the three main structures develope in this mass —the cricoid, arytmnoid, and chordal nodule. V.L. is the “ventral lamina ” involved behind in the ventral meeting of the t\vo cricoid halves, in front probably forming the lowest part of the inter-thyroid lamina, and between these two, developing into the middle part of the cricoid-thyroid membrane: the chordal nodule is attached to the ventral lamina and is continuous with the remaining part of the lateral mass.

The last—named structure ultimately becomes chondrified by extension from the thyroid, so that the nodule is attached to the ala of this cartilage, but in the meantime it undergoes modification.

Fig. 16 is a diagram from model VII., and shows the state of the nodule in the seventh week ; its connection with the other structures named is well shown, but it is considerably smaller, and its cell—continuity with the arytaenoid rudiment is becoming elongated. This degeneration of the nodule goes on. and as its ventral connections appear to be stronger than those on its dorsal side it remains closely attached to the ventral laminar structures, but the cell-strands that connect it with the arytaenoid and dorsal part of the cricoid become thinned out and weak; the latter seem to become broken down, but the f0rmer—th0se connecting it with the arytaenoid—remain and thicken as the true vocal cord.

The cord is thus very obliquely placed at first, but, as the arytaenoid settles down into its place, and the depth of the thyroid increases ventrally, it assumes its final position.

Fig. 16. A semi-diagrammatic sketch from a 22 mm. embryo showing the chordal nodule, a ready smaller, with its attachments to the cricoid and arytaenoid behind, and central crico-thyroid membrane and lower part of inter-thyroid lamina in front. The front attachments seem stronger than the others, so that these latter thin out and disappear, with the exception of the arytaenoid attachment, which thickens somewhat subsequently and forms the true cord (B). The arytaenoid ends above in a column of condensed cells, and is joined to the cricoid by similar tissue. T is placed in the transverse cavity and points to the indicating line of -the wall of the cavity. (The inter-thyroid lamina appears to be derived from the ventral lamina in its lowest part: its upper part is presumably formed as a 4th arch structure continuous with the thyroid rudiments.)

At the end of the second month the nodule, much reduced, exists as a small mass underlying the lowest part of the transverse cavity, at its junction with the floor of the sagittal part, and, by the end of the third month, it appears more as a spindle-shaped swelling on the ventral end of the cord. I have not seen it reach a truly cartilaginous state, but I presume it may do so occasionally, and so account for the small nodule of cartilage that is sometimes found in this part of the true cord.

A few other details connected with the cavity can be considered here.

The saccule is first seen as a definite outgrowth in my series of models at the end of the second month; its large size, bringing it out for some distance beyond the lateral limit of the transverse cavity, implies that it is an active outgrowth and not a part of this cavity cut off, and, moreover, must commence its growth at an earlier period.

- The saccule proper is probably only the outer end of this growth, the nearer part helping to form Morgagni’s ventricle in the more mature larynx, but from this point of view the saccular part would be the earliest part to grow out, so I have termed the whole the “ saccular” outgrowth.

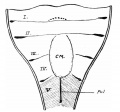

Fig. 17. A sketch of the outline of the adult cavity, with indications of the underlying cartilages, for comparison with figs. 12, 15 and 16. The second figure shows the final position of the original sagittal opening.

It is not apparent in the 22 mm. model, but the lining cells in this specimen were evidently in a state of proliferation, and the consequent limits of the cavity do not show up well.

In a small model of the side of the larynx in an 18 mm. embryo, cut sagitally, there is a decided increase in the breadth of the epithelial limits of the transverse part, though this increase does not affect the cavity (fig. 18); I cannot say whether this is an indication of the commencing outgrowth or not. Examination of numerous sections of this embryo and

those of 16 mm. and 22 mm. lengths, under a high power, have suggested the possibility of there being some destruction of the lateral lining cells of this part of the cavity, but this is no more than an occasional suggestion: so the cell thickness seen in the 18 mm. model might be a preliminary to disappearance, or might be the antecedent of the saccular bud.

So far as examination of the specimens and models goes, it is only possible to say that the saccule develops in the latter part of the second month, and is well marked by the end of the month as a hollow projection with an expanded fundus, issuing from the transverse cavity just above the position of the “chordal nodule.”

- It was suggested by Kohlbrügge that the saccule represents a visceral cleft or pouch : Kallius quotes this, an considers that, if this view is held, the ouch represented would be the 5th. It is apparent, if the account given here is followed, that this could not be the case, as the pouching is situated in front of the 5th arch, between it and the 4th arch element. I do not think the outgrowth can be looked on as in series with, or corresponding with, a visceral cleft or pouch proper, because it occurs secondarily in a secondary specialised formation ; but t at it has a definite connection with the line between the arches is very probable, and this connection may be a mechanical one——that the growth of the lining membrane of the transverse cavity that is evident in the 18 mm. embryo, for instance, only has its opportunity of progressing in the area between the arch cell-masses, where the resistance is presumably less.

The Walls of the original sagittal cleft are pressed together by the growing 5th arch mass, and the epithelial lining consequently adheres, so that, in the 5 mm. embryo and in later stages, the cleft is only a potential one in the greater part of its extent. But the main pressure is apparently exerted in the centre of the cleft area, and not so much in the periphery, and, as a result of this, a minute channel runs, from the front end of the fissured opening, along the floor of the cleft: this anterior or ventral channel is not always open at its front extremity.

Fig. 18. Shows the apparent protrusion (X) at the lower end of the transverse cavity of an 18 mm. embryo: the thickening affects the cellular lining and does not seem to increase the breadth of the cavity. The model is seen from the right and behind, and shows the 3rd arch element in the epiglottis.

Similarly, a posterior or dorsal channel—rather better marked—runs downwards and backwards from the hinder end of the fissure in the floor of the pharynx.

The two channels meet in the common lumen of the drawn-out air-tube, i.e. at the level of the hinder end of the 5th arch mass (fig. 19).

As the back part of this mass grows, the meeting of the two channels is at first drawn out, and later, as the cricoid develops and allows the, lumen to expand, their meeting becomes merged in the general opening up of the cavity.

In the meantime, the formation of the transverse cavity having taken place, this receives the front end of the ventral channel into its downwarddirected apex, at the angle formed between the two parts at their junction.

Fig. 19. Diagrams to show the ventral (V) and dorsal (D) channels left when the central part of the 5th arch mass (M) occludes the remainder of the original sagittal cavity. The later stages are opening up from below, owing to the formation of the cricoid. The transverse cavity opens, from its earliest stage, into the front end of the ventral channel.

In these later stages the channels may be partly obliterated by the increasing size of the 5th arch mass, before this is resolved into its ultimate products.

The general epithelial adhesion in the sagittal cleft begins its disappearance from below with the formation of the cricoid cartilage, and from above and in front with the “settling down” of the dorsal part of the 5th arch mass on the forming arytaenoid, and has practically gone by the end of the second or beginning of third month.

In the transverse cavity there may be some adhesion at first at the extremities of the limbs of the formation, but this does not last very long. The appearance of proliferation observed in the seventh week embryo does not seem to me to be the normal condition, but might be a change subsequent to the death of the embryo as a whole.

When the lateral masses are pushed forward by their hinder growths, to form the dorsal wall of the transverse cavity, they come up nearly to the level of the top of the epiglottis, and have the originally hinder part of the sagittal opening showing between them dorsally: by this time the cricoid is very large proportionately, as is the arytaenoid, and the former is largely and the latter partly chondrified, so that the mass is held as a whole more,or less in the position it has gained.

The extremity of the overlapping mass becomes less swollen and sinks »back on the underlying support, and in this way is slightly modified in _its level, at the same time opening up the part of the sagittal cavity that lies between it and its fellow: corresponding changes proceed in relation with the chordal region andthe cricoid.

This moulding into shape by reduction on the underlying structures in the sagittal cavity goes on mainly in the latter part of the second month.

A short summary of the general development of the cavity might now be given as follows :—

It is at first a simple sagittal cleft, bounded by the 5th arch masses, and elongated as growth proceeds.

The masses increase in size, and about the end of the first month are joined on each side by the 4th arch masses. The lateral mass thus formed on each side of the cleft grows forward, folding itself over the central mass, so that a secondary transverse cavity is built up, opening between the lateral masses into the original sagittal cleft. Thus the transverse cavity is really a modified part of the pharyngeal floor, and narrows to its apex below and behind. The ventral walls of the two parts thus formed meet in an angle, which remains in adult life: this angle corre ‘sponds with the apex of the transverse cavity. By the middle of the second month the depth of the transverse cavity is equal to that of the sagittal part.

After this the rapidly developing cartilages in the 5th arch mass form a supporting framework that holds the mass as a whole in the position it has gained, and the sagittal cavity lies between these developing cartilages, opening in front and ventrally into the transverse cavity.

The true vocal cord is developed in the front and ventral part of the 5th arch mass, so that it corresponds with this boundary of the sagittal cavity ; the rest of the boundary settles down on the arytaenoid, wherefore the line drawn along the cord and up the arytaenoid margin separates the sagittal cavity (pulmonary outgrowth) from the transverse part, which is a portion of the general pharyngeal cavity enclosed by the upgrowth of the lateral masses. ‘

The distinction between these two parts can be made evident if it is remembered that the line of the sagittal opening in the floor is the line of the boundary between the pulmonary and pharyngeal cavities, and its modification is simply shown in the scheme in fig. 12.

(B) The Development of the Remaining Structures in the Larynx

The 5th arch masses bounding the original sagittal cleft, and carried forward to form the dorsal wall of the transverse cavity, are composed of much condensed mesenchyme; in this condensation are laid down the cricoid and arytaenoid cartilages, and the apparatus connected with the true cords.

The ventral lamina is involved in the ventral junction of the two halves of the cricoid, and in_ front of this forms the central part of the crico-thyroid membrane, running still further forward into the lower part of the interthyroid lamina of cells intervening between the developing thyroid alae. Thus these structures are connected with the ventral parts of those developed in the 5th arch mass.

The outer cells of the 5th arch mass form the internal intrinsic muscles of the larynx, and the thyroid cartilage is laid down outside these again.

It will be convenient to describe first the development of the deeper tissues, and finally that of the thyroid and epiglottis.

In discussing this later development and describing the late models it will perhaps be more appropriate to use the terms of position that are employed in descriptive human anatomy.

Cricoid

The cricoid anlage is distinguishable in the sixth week as a concentration in the already condensed tissue of the 5th arch, on each side of the lower end of the laryngeal fissure ; its situation can be placed opposite the junction of the two more or less open channels to form the patent free tube, and for a little distance below this junction. This would probably put the point of development at the hinder end of the ventro-lateral 5th arch. The concentration is continued upward for some little distance beside the compressed and rapidly deepening sagittal cleft of the cavity: this extension upwards leaves uncompressed the back part of the cleft that contains the posterior channel.

The concentration fades away all round into the surrounding condensed mass, and through this is continuous above with the distinctly separate arytaenoid concentration. The model (fig. 6) shows the two early structures with their relation to the wall of the cavity, but it must be remembered that their outlines are not so definite as they must be in a model, and the open space all round them is filled up by the condensation of the ventro— lateral 5th arch. In the seventh week each half of the cartilage is partly cartilaginous below and in front, and is in a precartilaginousi condition behind and above, where it has closed completely round the cavity.

- This dorsal growth is elongating rapidly, and it is probably the rapid thickening of the mesenchyme that precedes it that is argely responsible for the pushing forward of the lateral masses over the central mass.

A thin bridge of cartilage unites the lower ends on the ventral side of the tube, and the arytaenoid anlage is more nearly continuous with its upper part. The ventral and dorsal junction of the two halves (with the corresponding growth) enables the lumen of the enclosed tube to become somewhat more rounded than in the earlier state: in both models there is a spur-like infolding of the back wall of the tube into the lumen, that is apparently due to the pressure of the cricoid while the lumen is increasing in size, but the size of this spur decreases in the succeeding specimens as the cartilage grows and the tube opens out. The model (fig. 7) shows the cartilaginous and precartilaginous cricoid, continuous above with the arytaenoid mass in a partly precartilaginous state, and between these and in front of them, and directly continuous with them, a third mass of condensed‘ mesoblast (chordal nodule) which in its turn is continuous, below the lower part of the transverse cavity, with the condensed interthyroid lamina.

The commencement of the cricoid is evidently bilateral, and situated nearer the dorsal than the ventral edge of the tube, as is shown in the 16 mm. embryo.

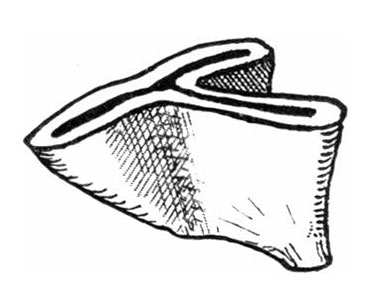

By the end of the second month (fig. 8) the cartilage has grown enormously; its rate of increase from its commencement has been out of all proportion to the increase in length of the embryo or of the cavity of the larynx, but after this period its growth is slower. The whole cartilage is chondrified and seems complete, with the exception of its ventral junction, where the connection between its two sides is still narrow: the pointed ends of the lateral halves are turned down here before they join, so that they form an upper notch which is bridged across by the central part of the crico-thyroid membrane. At the end of the third month this downward_direction is still apparent, but there is a tendency to close in the notch.

Arytenoid

This cartilage is closely applied to the laryngeal cleft, and is derived from the dorsal part of the lateral thickening, so that the posterior channel passes down behind it and its fellow.

The early concentration, noticeable during the sixth week (fig. 6), seems larger than that of the cricoid, from which it is separated by some little distance, the interval being filled by thickened mesoblast.

It does not grow rapidly like the cricoid, and chondrifies more slowly.

In the seventh week there is a decided precartilaginous condition observable just above the cricoid, with which it is connected by condensed tissue, while, above, it is continuous with a thickened column of cells that extend up towards the inner part of the top of the lateral mass, close against the contained cleft. In front and below it is continuous with a concentration that forms a mass in the angle between it and the cricoid, and, through this concentration, is connected with the interthyroid lamina below the lower end of the limb of the transverse part of the cavity. This concentration is the chordal nodule.

By the end of the second or beginning of the third month its shape is fairly well laid down in cartilage, but the vocal angle, that connects it with the concentrated mass in front of and below it, is still unchondrified, and its upper end is continued into a column of mesoblast as before. It is applied to the cricoid and connected with it by thick bands of cells, but there is no indication of a joint cavity. Examination of sections of the cartilage during the latter part of the third" month show that the vocal angle is apparently separately chondrified and fused with the arytaenoid.

Development of Intrinsic Muscles and Thyroid Cartilage

In an early embryo (5 mm.) two distinct sets of cells are apparent in the 5th arch mass; the deeper set that, with its fellow, compresses the cleft has outside it a layer of circular1y—disposed cells that is distinctly marked by reason of this disposition. This circular layer is found dorsally on the dorsal aspect of the pharynx, and passes down from this with and in front of the condensation of the arch, running between it and the 4th pouch, and so comes into relation with the side of the laryngeal cleft, from which, however, it is separated, as mentioned above, by the deeper condensation of the arch.

It does not extend quite so far forward as the deeper mass at this stage, but can be described as forming a layer situated outside the’ condensed main part of the mass. In an embryo of this size there is no corresponding circular layer found in connection with the 4th arch.

A little later, not only has this circular layer increased in extent forwards, but the 4th arch mesoblast, now becoming antero-external to it, has, in its turn, developed a circular layer in its outer part. Thus, during the fourth week, there are two planes of circularly disposed cells, separated from (me cmotherr by mesoblast of the 4th arch, the superficial plane belonging to the 4th arch, and the deeper plane being derived from the 5th arch and being separated by the condensation of the arch from the median cleft of the larynx.

The planes can be referred to as inner and outer constrictors: the inner constrictor appears to be subsequently split up into the internal intrinsic muscles in its laryngeal part, and dorsally forms part of the pharyngeal musculature, while the outer co'nstr'ictor becomes dorsally a superficial part of this musculature and, in its laryngeal area, gets a secondary attachment to the cricoid and thyroid, and seems to form the crico-thyroid muscle in consequence of the downgrowth of the inferior thyroid cornu into it.

It is diflicult to follow the details of the transformation of these constrictors, but the general process appears to be the following :—

Inner Constrictor

This is at first a tract of cells placed circularly round the pharynx and larynx, incomplete ventrally, so that its laryngeal part lies on the outer side of the 5th arch condensation.

The tract very soon gets attached to the ventro-lateral part of the pharynx, growing in between this and the drawn-out hinder end of the larynx—to which it is also attached,—so that by the end of the first month there is a more or less complete constrictor round the pharyngeal cavity (oesophagus) and one partially formed round the larynx ; this last is incomplete ventrally and only complete in the upper part dorsally, i.e. in the dorsal part of the 5th arch mass, behind the fissured opening, Where the pharyngeal portion is incomplete ventrally. The differentiation of the muscles after this seems to follow the formation and growth of the cartilages. The ventral end of the tract becomes attached to the cricoid and chordal nodule, the dorsal part running into the cricoid condensation below and being continuous across the middle line above. The formation of the arytaenoid seems to convert the dorsal hinder part into the crico—arytaenoideus posticus, the upper part into the arytaenoideus, and the ventral part into the thyro-arytaenoideus and lateral crico—arytaenoid.

The atrophy and ventral recession of the chordal nodule may perhaps draw the thyro—arytaenoid fibres more ventrally, but examination in later stages rather indicates that they have extended their area of attachment ventrally along the nodule.

Each of these intrinsic muscles thus appears to step at once from the primitive constrictor state into its proper position, the transformation being due to the development of the framework in sita.

The outer constrictor, continuous dorsally with the most superficial cells in the roof of the pharynx, passes, ventrally, to the outer side of the thyroid rudiment. It is found first, before this rudiment is recognisable, in the 7 mm. embryo. It is not easy to follow its further development after the thyroid rudiment is fairly well marked, owing to the near neighbourhood of other cells forming muscle strands in connection with the hyoid; but it appears to increase in thickness and in ventral prolongation, coming into contact in the sixth or seventh week with the cricoid, caudal and ventral to the small thyroid, which is on a plane internal to it.

As the thyroid cartilage increases in size, the fibres of the constrictor become attached to it externally, and when its lower cornu grows down to reach the cricoid, about the end of second or beginning of third month, this passes among the caudal fibres attached to the cricoid, and they thus assume an intermediate insertion into this cornu; and in this way apparently the crico-thyroid is formed, and its continuity with the constrictor is still evident over the lower cornu in 35 mm. and later specimens.

It appears, therefore, from these observations, that the outer constrictor is derived from the 4th arch and gives rise, among others, to the crico-thyroid, while the remaining intrinsic muscles are derivatives of the internal constrictor of the 5th arch system. The muscles in connection with the epiglottis have not been observed, there being no trace of them e_ven in the 6 cm. specimen, though the epiglottic cartilage was fairly well developed.

The Thyroid Cartilage

The small rudiment of this cartilage, shown in the 16 mm. model (fig. 6), seems to arise in a thick mass of closely packed cells that is situated, at the end of the first month, immediately in front of the 4th pouch and cleft, and somewhat ventral to them. It lies between the two constrictors, and is evidently a 4th arch structure; even in the 16 mm. specimen, Where the track of the 4th pouch can be found under the microscope, the rudiment that is seen in the model lies altogether on the cephalicside of that track. One is therefore driven to the conclusion that the thyroid anlage belongs to the 4th arch, and, if the cartilage contains‘ a 5th arch element, this is added afterwards, when the difliculty of determining the arch values of structures is enormously increased.

In the sixth week the thyroid concentration is directly continuous with that of the greater cornu of the hyoid, and, Very small in size, presents two ventral points. The continuity With the hyoid has its precursor in the 8'5 mm. embryo, where the mass of condensed mesoblast that lies in front of the 4th pouch is continued in a curve into the mesoblast of the 3rd arch. At the end of the seventh wee/c (fig. 7) chondrification has considerably progressed; Kallius describes two centres of chondrification for this cartilage, but I have not been able to hit upon their time of first appearance, which would, I presume, be about the first part of the seventh week.

In the model there are well-marked foramina in the cartilage, which seemed to be formed by the ventral junction of the two points noticed in the previous model. As these points occur on a rudiment that appears to be altogether a 4th arch structure, it would seem that the persistence of the foramen does not indicate the line of junction of a 4th and 5th arch element in the complete cartilage, but rather the failure of chondrification to involve the spot, possibly because the presence of a vessel or some other cause has kept the preliminary concentration of mesoblast from taking place there.

In the 16 mm. model the very small rudiments lie altogether lateral in the laryngeal region, connected with each other ventrally by a thick interthyroid lamina of cells; this is not shown in the model. The chondrifica— tion proceeds rapidly in the lamina, and in the 22 mm. model each ala is markedly convex externally, its ventral border turning in, in the plane of the lamina, towards its fellow; the two alae are much more widely separated above than below. The antero-inferior angle is elongated and turned down, tending to overhang the cricoid, and there is a suggestion of a commencing inferior cornu at the postero—inferior angle. The upper cornu is as long as the posterior border of the ala. In the 35 mm. model (fig. 8) the lower cornu is in contact with the cricoid, and the whole ala has evidently grown in length as well as in breadth; the former growth, so far as one can judge from not very reliable measurements, seems to affect the whole length of the structure (leaving the proportionate length of the upper cornu still the same), but the increase in breadth has come about by extension into the inter-thyroid lamina, so that the lower and anterior prominent angle is now a prominent tubercle or the lower border two-thirds of its length backwards. The alae are in contact in front, with the exception of the top part, where the incisura is showing; the upper borders exhibit the convex outline. Two small nodules of cartilaginous structure are interposed between the alae just below the incisura.

- I presume these represent the cartilages of Nicolas, but have been unable to obtain his original paper, so cannot be at all certain of this.

The cartilages form a large curve, convex forward and laterally, corresponding with the curved plane of the lamina into which the chondrification has spread.

The alee appear to meet ventrally at their lower ends first; in the 22 mm. model (fig. 7) there is a prolongation of the cartilaginous portion here which nearly reaches the middle line; this extension is somewhat downwards, involving the lowest part of the inter-thyroid lamina, so that the middle crico-thyroid part of the ventral lamina is directly attached to it, and the chordal nodule, which is fastened to the inter-thyroid lamina a little distance up (figs. 16, 17), in this way becomes attached to the meeting alae some distance above their lower margin, as can be seen in the 35 mm. model.

The small nodules that probably correspond with the cartilage of Nicolas are situated between the ala at the upper end of their junction, and appear to be connected with the cell strands that compose the false cords ; these are placed horizontally above the saccular dilatation, and pass from the front of the partly chondrified arytaenoid, at each side of the transverse cavity and the base of the epiglottic thickening in the front wall of this (with which they seem connected), to reach the small cartilaginous nodules.

The Epiglottis

The Epiglottis is a direct derivative of the central mass, and thus the morphological value of its greater part must remain doubtful from examination of human specimens. The 3rd arch, however, becomes clear across the middle line, showing as a ridge on the oral side of the prominence, noticeable even in an 18 mm. embryo. Thus this arch might be said to be represented on the front surface of the epiglottis, and the pharyngeepiglottic fold may possibly represent its lateral continuation.

The upper and outer part of the lateral mass (4th arch) is lost on the side of the central mass, here forming the lateral boundary of the upper opening of the transverse or pharyngeal part of the cavity, and this connection lengthens out as the lateral masses settle down on the arytaenoid, and becomes the ary-epiglottic fold.

The epiglottic cartilage commences as a loose concentration of small cells at the early part of the third month or end of second month, lying under the lining membrane of the centralmass. It increases slowly, not being very much more marked at the end of the third month than at the beginning. It seems to consist of a central thickened and rounded bar, with thinner wings at the sides: these wings first extend in their outer parts into the ary-epiglottic folds, and are apparently continuous below with the inner part of the false cords. The lower end of the structure lies opposite the lowest part of the area of “ Nicolas’ cartilages,” with which it seems to have some connection; it is not shown in the models except by colour to some extent.

I hope to return to the subject of the ontogenetic development of this cartilage at some future time—at present my observations on it are very incomplete, and I have made no reconstructions of it.

Summary of Results

The principal results obtaining from the study of the material and models may be shortly summarised as follows :—

- There is a 5th arch behind the 4th in the pharyngeal floor, subsequently becoming internal to it as well as behind, owing to the growth of the pharynx. ‘

- The opening of the pulmonary diverticulum lies between the two 5th arch masses, and behind a “central mass” in the middle line—the proximal end of the diverticulum is compressed between the 5th arch masses.

- The 5th arch is joined by the 4th to form a “lateral mass ” on each side of the opening, extending up along the side of the central mass.

- The lateral masses grow forward, overlapping the central mass from the line of its margin, and so form a secondary cavity, transverse in direction, wider above than below, and bounded ventrally by the central mass and dorsally by the two lateral masses.

- The transverse cavity is thus really a secondary inclusion of part of the cavity of the pharynx by an upgrowth of its floor, while the sagittal part is the drawn-out proximal end of the pulmonary diverticulum. An angle in the ventral wall marks the junction of the two parts even in the adult.

- These two parts of the cavity of the larynx are separated in the adult by a line drawn back along the true cord, and then upwards along the border of the arytaenoid eminence to the inter—arytaenoid notch. This line corresponds with the margin of the original sagittal opening in the pharyngeal floor.

- The true cords are developments in the continuity between the part of the 5th arch masses that lie respectively dorsal and ventral to the extreme lower or hinder end of the transverse cavity. Each cord is preceded by the appearance of a “chordal nodule,” whose subsequent atrophy leaves it attached to the thyroid junction and draws out the true cord as a strand of cells connecting it with the arytaenoid.

- The ventricle and saccules are outgrowths from the transverse cavity occurring just above the true cords.

- The arytaenoid and cricoid are developed in the 5th arch mass, the latter showing cartilaginous change before the former, by two centres placed laterally.

- The thyroid cartilage is primarily a 4th arch derivative, and, if it has a 5th arch element, this is a later addition, and its line of junction is not indicated by the occasional persistence of the foramen in the ala.

- The intrinsic muscles are derived from two planes of circularly arranged cells : the inner plane belongs to the 5tl1 arch, and gives origin to all the internal muscles, which depend for their differentiation on the growth of the cartilages, while the outer plane belongs to the 4th arch and appears to give rise to the crico-thyroid as a part cut off from the remainder (? inferior constrictor) by the downgrowth of the lower thyroid cornu.

- The epiglottis is derived from the central mass, and has a 3rd arch element in its oral and upper aspect: the arch value of the central mass is doubtful. The ary—epiglottic folds are elongated parts of the 4th arch element in the lateral mass that extended on to the sides of the central mass.

The remaining values of the adult larynx can be briefly given. The pharyngo—epiglottic fold is probably a remnant of the 3rd arch, the sinus pyriformis corresponds partly with the position of the 3rd pouch, while the situation of the 4th pouch can be put nearly opposite the lower end of the pharynx. The cornicular and cuneiform eminences mark the apices of those parts of the 5th and 4th arches respectively that lie dorsal to the transverse cavity.

The object of this work having been stated to be the provision of an account of the rmtogenetvlc origin of the larynx, I have refrained from any attempt to discuss the subject from the point of view of comparative anatomy. For the same reason, and because the results of the investigation were to be founded on the series of embryos which I had under observation, I have not been influenced by the views of others. In fact, the observations were made and this paper finished before consulting the literature on the subject, so that my ideas might remain unbiassed, save by‘ the rather meagre accounts in the English text-books and by a few scattered personal observations. It may at once be said, however, that the writings of Goppert, Kallius, and Strazza form a solid contribution to the subject under consideration. A comparison of the results of these researches with those set down in this paper shows many points of agreement, and also many of disagreement.

Space will not permit a discussion of the various points at issue, and the reader is referred to their well-known monographs. I may, however, remark that the reading of Göppert’s monograph on the cartilage of Wrisberg has reinforced my resolve to investigate further the ontogeny of the epiglottic cartilage, but his extensive research, being mainly of a comparative nature, has no immediate bearing on the object of the present paper.

Kallius’ work forms the basis of the modern account of the development of the larynx; it would be impossible to consider fairly the points of difference between his conclusions and those given here without adding very much to the considerable length of the present paper, so that I have limited my notice of his important contributions to a note on the ventricle of the larynx, which seems to be specially required.

Strazza has written on the development of the muscles of the human larynx, and found the same difficulty in Working out the details of the process. He did 11ot seem to have early material on which to make his observations, and considers, with Ganghofer, that these muscles are continuous mesoblastically with those of the tongue. I confess that I find it diflicult to follow the meaning of this statement, unless it implies that the muscles are developed under the pharyngeal floor, — where the later mesoblast is certainly continuous along its whole length, as also in the roof and elsewhere—and any continuity other than this I have not observed. He calls attention to the likeness of the earlier state of the musculature to Furbringer’s pharyngo-laryngeal constrictor of mammalia.

Strazza considers that the posterior arytaenoideus is the first muscle to develop separately, but I find it hard to agree with this statement, and look on it merely as more easily recognisable from its position; certainly it is not present when the “inner constrictor ” is well marked.