Book - Manual of Human Embryology 17

| Embryology - 30 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Grosser O. Lewis FT. and McMurrich JP. The Development of the Digestive Tract and of the Organs of Respiration. (1912) chapter 17, vol. 2, in Keibel F. and Mall FP. Manual of Human Embryology II. (1912) J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

XVII. The Development of the Digestive Tract and of the Organs of Respiration

By Otto Grosser, Prague; Frederic T. Lewis, Harvard University; and J. Playfair Mcmurrich, University of Toronto.

- Introduction Frederic Lewis

- Early Development of the Entodermal Tract and the Formation of its Subdivisions Frederic Lewis

- The Mouth and Its Organs J. Playfair McMurrich

- The Development Of The Oesophagus Frederic Lewis

- The Development of the Stomach Frederic Lewis

- The Development of the Small Intestine Frederic Lewis

- The Development of the Large Intestine Frederic Lewis

- The Development of the Liver Frederic Lewis

- Development of the Pancreas Frederic Lewis

- The Pharynx and its Derivatives Otto Grosser

- The Development of the Respiratory Apparatus Otto Grosser

Introduction

Formation of the Intestines from the Umbilical Vesicle

In the youngest human embryos which have yet been obtained, the entoderm forms the lining of a more or less spherical sac, which the early anatomists named the umbilical vesicle (vesicula wnbilicalis). The vesicle enlarges with the growth of the embryo, and during the second month it is a conspicuous object. At birth it is still present.

It was observed at birth by Hoboken, in 1675, as a granule of oval shape, white, about the size of a hemp-seed, with indurated contents. It was probably the umbilical vesicle which Diemerbroeck found in an embryo of the sixth week, and described in 1672 as a sac, the size of a small hazel-nut, filled with clear fluid. But the first satisfactory description of this structure in a human embryo is credited to Albinus, who published an excellent drawing of it in 1754, and referred to it as the vesicula ad umbilicum parvuli embryonis. The vesicle was lodged between the amnion and chorion near the distal end of the umbilical cord, and a slender thread-like prolongation extended from it, through the cord, to the body of the embryo. Beyond this point Albinus did not follow it for fear of damaging his specimen.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century the umbilical vesicle was recognized as a constant structure in young human embryos and its significance was being discussed (Lobstein, 1802). Wrisberg had shown that blood-vessels passed from it into the mesentery of the embryo. Oken believed that the embryo was nourished through the umbilical vesicle, and in 1806 he published a notable treatise, in which he declared that the following propositions would be proved with absolute certainty:

- The intestines of embryos originally do not lie in the abdominal cavity, but arise from a vesicle, situated outside of the amnion, called the vesicula umbilicalis in man, and the tunica erythroides in other animals.

- The intestines do not lie in the vesicle as in a sac. but they are a prolongation of it, as the duodenum is a prolongation of the stomach. The prolongation splits into an anterior and a posterior intestine, both of which pass through the umbilical cord into the abdominal cavity, one part going to the anus, the other to the stomach.

- The stalk of the vesicle, between the splitting of the intestine and the vesicle, becomes obliterated after some weeks, closing and becoming cut off like an umbilical artery; it appears at first as the caecum, and later also as the vermiform process, so that at this place there is no continuity in the intestines but an angular splicing- with a valve.

- The intestines now begin to draw back toward the umbilicus and finally enter the abdominal cavity, so that all embryos necessarily have the so-called umbilical hernia.

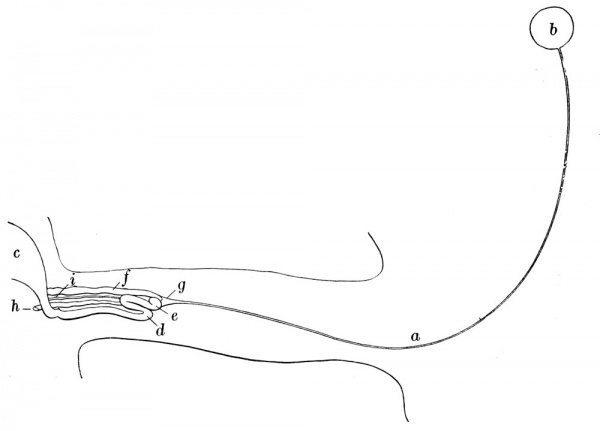

These propositions were defended by Kieser in 1810, who published an interesting figure of the intestines of a three months' human embryo, a reduced copy of which is shown in Fig. 223. He found that the coils of the intestine were lodged in the umbilical cord and not in the abdominal cavity. He was uncertain whether the intestinal tube continued across the insertion of the stalk of the umbilical vesicle, but, influenced by Oken, he wrote, " It appears as if the ends of the two parts of the intestine were here still divided." The gastric portion is represented as ending in a knob-like expansion, which is in contact with the blunt end of the anal half of the intestine and with the cord of the umbiHcal vesicle, at a place where later the caecum and vermiform process will appear. The cord of the vesicle is a prolongation of the mesentery, in which both the blood-vessels and the tube connecting the vesicle with the intestine have become obliterated.

Fig. 223. — Kieser's figure, reduced and re-lettered, showing the umbilical cord of a human embryo of three months, the intestines within it, the cord of the umbilical vesicle (a), and the vesicle itself (6); c, lower part of stomach; d, coil of the gastric portion of the intestine which has a blunt end at e; f, anal part of the intestine, also with a blunt end; g, "cord of the umbilical vesicle as it surrounds the two ends of the intestine like a funnel; " h, vena omphalo-mesenterica; i, arteria omphalo-mesenterica.

In Oken's chapter entitled " Proof that all mammals possess an intestinal vesicle and that the intestines arise from it," he says, " I could easily extend this proof over the classes of egg-laying animals." The human umbilical vesicle had already been compared with the yolk-sac of birds, and in 1768 Caspar Friedrich Wolff had published his fundamental studies upon the development of the intestine in the chick. He found that the primitive intestinal cavity is in the dorsal part of the yolk. From this cavity he saw a slender prolongation, which admitted a fine needle, grow forward to make the stomach and oesophagus. This prolongation is called the fore-gut. Somewhat later in the development of the chick, Wolff saw a similar prolongation grow backward to make the rectum, and this is the hind-gut. Between the two is the mid-gut, open below toward the yolk, and becoming relatively small as the fore-gut and hind-gut lengthen, partly at its expense. Thus Wolff saw in the chick what Oken later conjectured for man, and what has since been actually observed, namely that the intestine arises by the outgrowth of foregut and hind-gut respectively, from the dorsal part of the cavity of the yolk-sac.

Separation of the Intestines from the Yolk-sac

The term yolk-sac, sacculus vitetlinus, since it is applicable both to lower animals and to man, has largely replaced the term umbilical vesicle. The name mid-gut, although in common use, may well be abandoned. The fore-gut can then be sharply denned as that portion of the intestine anterior to the attachment of the yolk-sac, and the hind-gut as the part which is posterior. The attachment of the yolk-sac, broad at first, becomes reduced to a slender stalk, the base of which may remain as a diverticulum of the intestine.

Oken wrongly supposed that a portion of the yolk-stalk persists as the vermiform process. This error was corrected by Meckel (1812) in a most thorough manner. An out-pocketing of the human small intestine, usually about an inch in length but sometimes several times as long, had frequently been observed. It was generally found opposite the mesenteric attachment, about three feet from the beginning of the large intestine. Sometimes it was turned toward the mesentery. Its walls included all of the layers which enter into the formation of the intestinal tube, with which its lumen was in free communication. Meckel regarded the opinion of Fabricius, that such diverticula arise from the pressure of substances within the intestinal canal, as improbable. He saw the diverticulum several times in children at birth, once in an embryo of six months and twice at three months. Since it is a congenital structure, essentially constant in position, Meckel sought to explain it through the normal development of the intestinal tract, and concluded as follows : " Even into the third month of embryonic life a small elevation remains in the lower part of the small intestine as a trace of the former connection (with the yolk-sac), and if this is retained beyond this time it appears as a blind appendage." Meckel found one abnormal case in which it remained as an open duct extending from the intestine to the umbilicus, accompanied by its vessels which were still pervious. He saw cases also in which the obliterated vessels formed cords extending from the diverticulum of the intestine across the abdominal cavity to the umbilicus. Such cords have frequently been observed, and, as Meckel recorded, they may leadt-to adhesions and intestinal obstruction. The diverticulum was found not only in man but in other mammals. Cuvier had seen it in birds, and Meckel concluded that it was a constant structure in ducks and geese, in which, moreover, its genesis from the yolk-sac could be clearly demonstrated. Thus the true embryonic interpretation of the diverticulum ilei was clearly established by Meckel. He found also that " the vermiform process appears first as a little knob which gradually enlarges considerably." " I saw it arise thus in the human embryo, as Wolff had seen the caeca in the chick, where previously no trace of them could be identified.' - ' This conclusion is in accord with later observations.

The Allantois

Several human embryos have been obtained which are so young that neither the fore-gut nor the hind-gut has begun to grow out from the cavity of the yolk-sac. In most of these, however, the tubular entodermal outgrowth known as the allantois is present. The allantois grows out from the posterior portion of the yolk-sac near its dorsal surface. When the hind-gut pushes out, the allantois is carried with it, so that then it empties into the terminal part of the hind-gut, which is called the cloaca.

In the horse, cow, and pig the distal portion of the allantois dilates enormously, forming a somewhat cylindrical vesicle, so attached to its stalk that the entire allantois is T-shaped. At certain stages the terminal vesicle is many times the size of the embryo. Thus, with an embryo goat of eighteen days Haller found an allantoic sac two feet long, whereas the embryo itself measured less than two inches (twenty lines). The allantoic sac is found between the amnion and the chorion, to which it may be adherent.

The part of the allantois near the intestine, which develops through subdivision of the cloaca, is commonly called the allantoic stalk. Its formation will be fully considered in the chapter on the urogenital tract. 1 A part of the allantoic stalk expands to form the bladder. Between the apex of the bladder and the allantoic sac, the allantois remains slender and is known as the urachus. The urachus extends from the bladder into the umbilical cord.

The allantois has been known for centuries. According to Fabricius ab Aquapendente (1600'), " The membrane is called aXkavroeuS^g because it is similar to aXkag, that is, sausage. But it must not be understood that it resembles anything filled with chopped meat, with which sausage skins are usually filled (for it contains only urine), but because its form seems similar to a sort of intestine from which sausages are generally made; hence it is called allantoic, that is, intestinal, by Galen and early writers. According to Suidas, a/ldq seems generally to be used in the sense of svrepov, although this too cannot be denied, that in such membranes, along with urine, particles like chopped meat or sausage are sometimes found." The solid particles referred to may be the hippomanes found in the allantois of the horse, and said to be known to Aristotle (Bonnet, 1907, p. 194).

Many attempts were made to find an allantois in human embryos, but at the beginning of the nineteenth century no agreement had been reached. Hale in 1701 had announced " The Human Allantois discover'd," but. according to Oken and Velpeau, it was probably an amnion which he described. Lobstein declared that the human yolk-sac was the allantois. " Who will not be entirely in doubt," Oken wrote in 1806, " when one finds that writers have described as allantois the most heterogeneous things which were ever seen ? " It soon became established, however, that in human embryos a slender urachus extends from the bladder into the umbilical cord, accompanied by the umbilical arteries. Velpeau, in 1834, thought that after the urachus had passed the whole length of the cord it became lost in a porous tissue between the amnion and the chorion, and that this tissue represented the allantoic sac. Von Baer, in 1837, declared that what was found between the amnion and the chorion had been somewhat rashly interpreted as the allantois. " The true allantois it certainly is not.

- Allantoic vesicles continued to be reported for many years, until finally the fundamental relations of the human allantois were established by His. He wrote as follows (1885, p. 222) : “I designate as body-stalk [pedunculus abdominalis] that thick cord which in very young embryos forms a connection between the 1 See also page 322. embryo and the chorion. . . . The main portion of the body-stalk is loose connective tissue with a few smooth muscle-cells; its dorsal surface has an ectodermal covering, and the ventral half surrounds the allantoic duct and the two umbilical arteries running with it. ... A vesicular or even only a free allantois has never been found in human embryos, and the slender duet in the body-stalk, the allantoic duct as I have formerly named it, is indeed only a very rudimentary representative of the structure which is so large in many mammals." Although the human allantois may be described as rudimentary because of its small size, it is nevertheless differentiated very early. Keibel and Elze (1908, p. 152) have recorded that it appears in man and the apes before any segments have formed.

It arises somewhat later in Tarsius, but still before there are any segments. It first appears in pigs of four or five pairs of segments, in rabbits of about eleven pairs, and in chicks of more than twenty pairs.

In the first human embryo which is now to be described, the body-stalk will be seen connecting the yolk-sac with the chorion. Into this stalk in the second specimen the allantois has grown out, thus forming the first subdivision of the entodermal tract.

| Embryology - 30 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Grosser O. Lewis FT. and McMurrich JP. The Development of the Digestive Tract and of the Organs of Respiration. (1912) chapter 17, vol. 2, in Keibel F. and Mall FP. Manual of Human Embryology II. (1912) J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 30) Embryology Book - Manual of Human Embryology 17. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_Manual_of_Human_Embryology_17

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G