Book - The Pineal Organ (1940): Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Header}} | {{Header}} | ||

{{Ref-GladstoneWakeley1940}} | {{Ref-GladstoneWakeley1940}} | ||

{{GladstoneWakeley1940 TOC}} | |||

{| class="wikitable mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" | ||

! Online Editor | ! Online Editor | ||

| Line 6: | Line 7: | ||

| [[File:Mark_Hill.jpg|90px|left]] This historic 1940 book by Gladstone and Wakeley describes the pineal gland - the comparative anatomy of median and lateral eyes, with special reference to the origin of the pineal body; and a description of the human pineal organ considered from the clinical and surgical standpoints. | | [[File:Mark_Hill.jpg|90px|left]] This historic 1940 book by Gladstone and Wakeley describes the pineal gland - the comparative anatomy of median and lateral eyes, with special reference to the origin of the pineal body; and a description of the human pineal organ considered from the clinical and surgical standpoints. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[https://archive.org/details/pinealorgancompa00glad/page/n5/mode/2up Internet Archive] | [[Media:1940_The_Pineal_Organ.pdf|PDF version]] | [https://archive.org/details/pinealorgancompa00glad/page/n5/mode/2up Internet Archive version] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

'''Modern Notes:''' {{pineal}} | {{endocrine}} | '''Modern Notes:''' {{pineal}} | {{endocrine}} | ||

| Line 20: | Line 21: | ||

By | By | ||

{| | {| | ||

| '''Reginald J. Gladstone''' | | valign=top|'''Reginald J. Gladstone''' | ||

M.D., F.R.C.S., F.R.S.E., D.P.H. | M.D., F.R.C.S., F.R.S.E., D.P.H. | ||

| Line 35: | Line 36: | ||

Of The Zoological Society Of London | Of The Zoological Society Of London | ||

| And | | valign=top|And | ||

| Cecil P. G. Wakeley | | valign=top|'''Cecil P. G. Wakeley''' | ||

D.Sc, F.R.C.S., F.R.S.E., F.Z.S., F.A.C.S., F.R.A.C.S. | D.Sc, F.R.C.S., F.R.S.E., F.Z.S., F.A.C.S., F.R.A.C.S. | ||

| Line 50: | Line 51: | ||

Hunterian Professor Royal College Of Surgeons Of England | Hunterian Professor Royal College Of Surgeons Of England | ||

|} | |} | ||

<br> | |||

London Bailliere, Tindall And Cox | London Bailliere, Tindall And Cox | ||

| Line 67: | Line 70: | ||

==Foreward== | ==Foreward== | ||

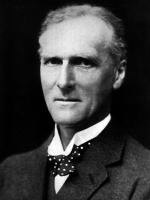

[[File:Arthur_Keith.jpg|thumb|150px|alt=Sir Arthur Keith (1866 - 1955)|link=Embryology History - Arthur Keith|Sir Arthur Keith (1866 - 1955)]] | |||

By Sir Arthur Keith, F.R.S. | By [[Embryology History - Arthur Keith|Sir Arthur Keith, F.R.S.]] | ||

I should mislead readers were I to assure them that this book, written | I should mislead readers were I to assure them that this book, written by an anatomist who has given half a century to the elucidation of the human body and by a surgeon who stands in the forefront of his profession, reads as easily as a work of fiction. Books which are fundamental in character are not easy reading, and this is a work of the kind. And yet the story which Dr. Gladstone unfolds is a romance. To trace the origin and evolution of the human pineal body or epiphysis, he has had to go back to an early stage of the world of life, one some 400 millions of years removed from us, when median as well as lateral eyes had appeared on the heads of our invertebrate ancestry. His search has not been confined to the geological record ; he has brought together from the literature of comparative anatomy and from his own observations what is known of median eyes and the pineal organ in all types of living forms, both invertebrate and vertebrate. | ||

by an anatomist who has given half a century to the elucidation of the | |||

human body and by a surgeon who stands in the forefront of his profession, reads as easily as a work of fiction. Books which are fundamental | |||

in character are not easy reading, and this is a work of the kind. And | |||

yet the story which Dr. Gladstone unfolds is a romance. To trace the | |||

origin and evolution of the human pineal body or epiphysis, he has had | |||

to go back to an early stage of the world of life, one some 400 millions of | |||

years removed from us, when median as well as lateral eyes had appeared | |||

on the heads of our invertebrate ancestry. His search has not been confined to the geological record ; he has brought together from the literature | |||

of comparative anatomy and from his own observations what is known of | |||

median eyes and the pineal organ in all types of living forms, both invertebrate and vertebrate. | |||

If Dr. Gladstone's story begins in a past which is very distant, that | If Dr. Gladstone's story begins in a past which is very distant, that which Mr. Wakeley has to tell belongs to the present and the future. His story opens a new chapter in surgery, that which is to deal with the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the pineal body. | ||

which Mr. Wakeley has to tell belongs to the present and the future. His | |||

story opens a new chapter in surgery, that which is to deal with the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the pineal body. | |||

It is many years since Dr. Gladstone and I became students and | It is many years since Dr. Gladstone and I became students and friends at the University of Aberdeen, and friends and students we have remained ever since. We have in that time seen strange changes in the anatomy of the human body — structures such as the pituitary, thyroid, and adrenal, which we counted negligible, soar to positions of dominance ; we have seen parts of the brain such as the hypothalamus, which we regarded as mere wall-space of the third ventricle, become the seat of fundamental and vital processes ; and we have seen some structures dethroned. Although the " pineal gland " had fallen from its high estate long before Gladstone and I became students, it is of interest to compare the opinion which Descartes formed of it in the seventeenth century with the conclusions reached by our authors in the twentieth century. | ||

friends at the University of Aberdeen, and friends and students we have | |||

remained ever since. We have in that time seen strange changes in the | |||

anatomy of the human body — structures such as the pituitary, thyroid, | |||

and adrenal, which we counted negligible, soar to positions of dominance ; | |||

we have seen parts of the brain such as the hypothalamus, which we | |||

regarded as mere wall-space of the third ventricle, become the seat of | |||

fundamental and vital processes ; and we have seen some structures | |||

dethroned. Although the " pineal gland " had fallen from its high estate | |||

long before Gladstone and I became students, it is of interest to compare | |||

the opinion which Descartes formed of it in the seventeenth century with | |||

the conclusions reached by our authors in the twentieth century. | |||

Those who are familiar with The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy | Those who are familiar with The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy will recall Mr. Shandy's wish to discover " that part where the soul principally took up her residence." Let me quote from the original : | ||

will recall Mr. Shandy's wish to discover " that part where the soul | |||

principally took up her residence." Let me quote from the original : | |||

" Now from the best accounts he had been able to get of this matter, he | " Now from the best accounts he had been able to get of this matter, he was satisfied it could not be where Des Cartes had fixed it upon the top of the pineal gland of the brain, which, as he philosophized, formed a cushion for her about the size of a marrow pea ; this to speak the truth, as so many nerves did terminate all in that one place, it was no bad conjecture." | ||

was satisfied it could not be where Des Cartes had fixed it upon the top | |||

of the pineal gland of the brain, which, as he philosophized, formed a | |||

cushion for her about the size of a marrow pea ; this to speak the truth, | |||

as so many nerves did terminate all in that one place, it was no bad | |||

conjecture." | |||

Readers will remember how Uncle Toby knocked the bottom out of Descartes' theory by relating the case " of a Walloon officer at the battle of Landen, who had one part of his brain shot away by a musket ball — and another part of it taken out after by a French surgeon, and after all, recovered and did his duty very well without it." | |||

the | |||

I | I need not anticipate the conclusions reached by our authors regarding the nature and function of the pineal body of the human brain ; they will be found in the concluding chapter of this book. In spite of all their labours, much remains enigmatic concerning the pineal body ; but they have laid a basis from which those who would go further must set out. | ||

the authors | |||

I must not be like a too loquacious chairman and abuse the privilege the authors have given me, in writing the foreword, by intruding my own opinions. Yet at the risk of sinning in this respect, there are one or two observations I have picked up in my recent reading, which seem to throw light on some of the problems discussed by them. There is first an observation made by Wislocki and King {Amer. Journ. Anat., 1936, 58, 421), who on injecting a solution of trypan blue in the live animal, found that it stained certain nuclear structures in the hypothalamus and also the cells of the pineal body — an outgrowth from the epithalamus. There are structural resemblances in the parts so stained. Such an observation fits easily into the final conclusions drawn by our authors. Hypothalamus and epithalamus, so widely separated by the thalamus in the human brain, were anciently close neighbours, both being associated with olfactory tracts and connections. Both are constituent parts of that cavity of the brain from which the lateral eyes as well as the median or parietal eye are developed. | |||

there are | |||

eye | |||

Our authors find that the evidence which attributes a sex function to the pineal body is confused and contradictory, and rightly in my opinion bring in, on this head, a verdict of " unproven." Before we finally reject the evidence, however, it seems well to remember that through our retinae, there are transmitted to the brain not only stimuli which give rise to vision but also " light reflexes." It seems probable that the median as well as the lateral eyes had this double function. Through centres in the hypothalamus and pituitary, light reflexes can bear in upon the gonads and regulate their times of ripening. Prof. Le Gros Clark and his colleagues (Proc. Roy. Soc, 1939, 126 (B), 449) by cutting the optic nerves of the ferret and thus cutting off light reflexes, altered the onset of the period of heat. One can best explain the connection of the habenular ganglia of the pineal with the hypothalamus (through the striae medullares) by supposing that the median or parietal eye did exercise an influence on the hypothalamus and pituitary. Nor is it unreasonable to suppose that, in connection with sex-function, there arose in the basal part of the diverticulum which gives rise to the pineal organ an area or segment of nerve-cells, which, like certain groups in the hypothalamus, are neuro-secretory in nature. With the disappearance of the parietal eye in birds and mammals, this basal part embedded in the epithalamic system, persisted in them to form the pineal body. | |||

I count it a privilege to have had the opportunity of reading this work while it was still in proof-form. I have learned much from it and I am sure others will benefit from its study as much as I have done. I would especially endorse a sentence in the first chapter, which reads : | |||

to | |||

" As one branch of medicine advances it becomes repeatedly necessary to fall back on the fundamental sciences for help and guidance, and realizing that the investigation of these pineal tumours proved rather barren some years ago, the authors determined to investigate the whole question of the nature of the pineal organ from the lowest to the highest forms in the animal kingdom." | |||

By so doing they have shown themselves to be true disciples of John Hunter. | |||

ARTHUR KEITH. | |||

Buckston Browne Research Farm, Downe, Kent, | |||

October 28th, 1939 | |||

==Preface== | ==Preface== | ||

This book is the outcome of a desire to study the pineal body from the | This book is the outcome of a desire to study the pineal body from the broad standpoint of comparative anatomy, and to correlate as far as possible the structural appearance and connections of the mammalian epiphysis with the conflicting views which are held with regard to its origin and functions. | ||

broad standpoint of comparative anatomy, and to correlate as far as possible | |||

the structural appearance and connections of the mammalian epiphysis | |||

with the conflicting views which are held with regard to its origin and | |||

functions | |||

It was originally intended to deal with the subject mainly from the practical standpoints of diagnosis and operative technique, based upon the exact anatomical relations and connections of the pineal organ in the human subject. It soon became evident, however, that the study involved a much wider basis than the purely anatomical and clinical, and in order to assess the true significance of the facts which have been observed in connection with the mammalian epiphysis it would be necessary to investigate the history of the pineal body and parietal sense-organ from the standpoints of embryology, conparative anatomy, and geology. This, study raises further questions which are of great biological importance such as the influence which heredity appears to have in causing the retention for millions of years of an organ which in the majority of living vertebrate animals has completely lost its original function of a visual sense-organ ; also the problems that are raised by the recent hypothesis that the pineal body of the higher vertebrate classes is evolving as an endocrine organ by transformation of the vestigial parietal sense-organ into a gland of internal secretion, or the alternative supposition, that the mammalian epiphysis is a genetically distinct structure which has arisen independently of the parietal eye of fishes and reptiles. Another problem which has engaged the attention of previous investigators, and which we have discussed in the light of recent palaeontological work, is the explanation of the coexistence of a general similarity in structure of the pineal eyes of vertebrates and the median eyes of invertebrates along with certain differences in detail, which also exist, and which were formerly considered to exclude any possibility of the two systems being genetically connected. One of the first fruits of this inquiry was the definite confirmation which we found is afforded by palaeontology and comparative anatomy of the primarily bilateral origin of the parietal sense-organ ; and a second the conviction which was gained of the extreme antiquity of the pineal system — this seems not only to have evolved before the evolution of the roof-bones of the vault of the skull but in some types of primitive fish to have already entered the regressive phase of its ancestral history at the time when the dermal bones of the skull had first completely covered over the brain and formed a protective investment for the principal sense-organs, namely the olfactory, visual, and static. | |||

study of | |||

of | |||

is | |||

of the system | |||

The authors hope that the book will be of interest to readers outside as well as within the medical profession and that it will stimulate the study of other organs and systems of the human body from the standpoint of comparative anatomy, in addition to the purely practical aspect. We feel assured that the wider outlook which is gained by the investigation of any particular structure by the embryological and comparative methods well repays the additional time which is spent in acquiring this knowledge. It not only greatly increases interest in the particular organ which is being studied but it also gives a better insight into the special functions of the system both in health and disease. | |||

Special care has been taken in selecting and making the illustrations, each of which has an independent explanatory legend. They have been assembled from various sources ; some are original drawings made specially for this work or which have previously been published by either one or both of us in the British Journal of Surgery, the Journal of Anatomy, or the Medical Press and Circular. Others have been reproduced from blocks, redrawn from lithographic plates, photographs, or drawings illustrating original papers, or from well-known standard works. The source of the latter has in each case been duly acknowledged, and the authors desire to take this opportunity of expressing their gratitude to the publishers and authors who have generously allowed us to make use of these figures ; and we desire specially to thank the publishers of those journals and books from which certain of the illustrations have been reproduced : John Wright and Sons, Bristol ; Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, London ; Quarterly Journal of the Microscopical Society, London ; Cambridge University Press ; Macmillan and Co., London ; Contributions to Embryology, John Hopkins University. | |||

published | |||

of the | |||

The authors also wish to acknowledge their indebtedness to the published works of all those writers whose names appear in the bibliography and in the following list. These works have been of the greatest value in determining the general trend of the book and an aid in coming to the conclusions which we have been enabled to draw from our own observations and experience. We wish especially to mention the names of the following authors : Achucarro, Agduhr, Ahlborn, Altmann, Amprino, Bailey, Badouin, de Beer, Beraneck, Berblinger, Bernard, Bertkau, Bourne, Brown, Cairns, Cajal, Calvet, Cambridge Natural History, Cameron, Cushing, Dandy, Dendy, Dimitrowa, Eycleshymer, Favaro, Foa, Gaskell, Globus, Goodrich, Grenacher, Harris, Haswell, Hill, C, Howell, Huxley, T., Huxley, J., Izawa, Kiaer, Kappers, Kerr, Kishinouye, Klinckostroem, Kolmer, Krabbe, Lang, Lankester, Leydig, Lereboullet, L'Hermitte, MacBride, MacCord, Marburg, Nicholson, Nowikoff, Parker, G. H., Parker and Haswell, Pastori, Patten, Penfield, Quast, Rio de Hortega, Schwalbe, Spencer, Stensio, Stormer, Strahl and Martin, Studnicka, Tilney and Warren, van Wagenen, Watson, Woodward, A. S., Zittel. | |||

and | |||

We | We desire, further, to gratefully acknowledge the help which we have received from Professor Doris L. MacKinnon of the Department of Zoology, King's College, London, and Dr. J. A. Hewitt, Lecturer on Physiology and Histology, King's College, London, for permission to make use of the specimens of Geotria and Sphenodon which belonged to the late Professor Arthur Dendy, and specimens from the Department of Histology from which some of the illustrations have been drawn. We also wish to thank Professors A. Smith Woodward, D. M. Watson, and W. T. Gordon, for valuable help with respect to references to literature, and Mr. Walpole Champneys and Margaret M. Gladstone for assistance in drawing some of the illustrations. | ||

We also wish to express our thanks to Mr. E. J. Weston, Mr. Charles Biddolph, and Mr. Denys Kempson for the valuable assistance they have given in the preparation of serial sections of embryos and microphotographs. Lastly, we would like to thank Miss Mil ward Smith and Miss Mary Popham, who between them have typed the whole of the manuscript. | |||

R. J. G. C. P. G. W. | |||

London, | |||

November, 1939 | |||

==Contents== | ==Contents== | ||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 1|Introduction]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 2|Historical Sketch]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 3|Types of Vertebrate and Invertebrate Eyes]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 4|Eyes of Invertebrates : Coelenterates]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 5|Flat worms]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 6|Round worms]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 7|Rotifers]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 8|Molluscoida]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 9|Echinoderms]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 10|Annulata]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 11|Arthropods]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 12|Molluscs]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 13|Eyes of Types which are intermediate between Vertebrates and Invertebrates]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 14|Hemichorda]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 15|Urochorda]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 16|Cephalochorda]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 17|The Pineal System of Vertebrates: Cyclostomes]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 18|Fishes]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 19|Amphibians]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 20|Reptiles]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 21|Birds]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 22|Mammals]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 23|Geological Evidence of Median Eyes in Vertebrates and Invertebrates]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 24|Relation of the Median to the Lateral Eyes]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 25|The Human Pineal Organ : Development and Histogenesis]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 26|Structure of the Adult Organ]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 27|Position and Anatomical Relations of the Adult Pineal Organ]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 28|Function of the Pineal Body]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 29|Pathology of Pineal Tumours]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 30|Symptomatology and Diagnosis of Pineal Tumours]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 31|Treatment, including the Surgical Approach to the Pineal Organ, and its Removal: Operative Technique]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 32|Clinical Cases]] | |||

# [[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) 33|General Conclusions]] | |||

[[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) Glossary|Glossary]] | |||

[[Book - The Pineal Organ (1940) Bibliography|Bibliography]] | |||

Bibliography | |||

Latest revision as of 08:50, 27 August 2020

| Embryology - 21 Jun 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Gladstone RJ. and Wakeley C. The Pineal Organ. (1940) Bailliere, Tindall & Cox, London. PDF

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

The Pineal Organ

The Comparative Anatomy of Median and Lateral Eyes, with Special Reference to the Origin of the Pineal Body ; and a Description of the Human Pineal Organ Considered from the Clinical and Surgical Standpoints

By

| Reginald J. Gladstone

M.D., F.R.C.S., F.R.S.E., D.P.H. Formerly Reader In Embryology And Lecturer On Anatomy, At King's College, University Of London, And Lecturer On Embryology At The Medical College, Middlesex Hospital, London J Member Of The Anatomical Society Of Great Britain And Ireland ; Formerly Fellow Of The Royal Anthropological Institute, And Fellow Of The Zoological Society Of London |

And | Cecil P. G. Wakeley

D.Sc, F.R.C.S., F.R.S.E., F.Z.S., F.A.C.S., F.R.A.C.S. Fellow Of King's College, London, And Lecturer In Applied Anatomy At King's College, University Of London ; Senior Surgeon, King's College Hospital And The West End Hospital For Nervous Diseases; Consulting Surgeon To The Maudsley Hospital And To The Royal Navy ; Hunterian Professor Royal College Of Surgeons Of England |

London Bailliere, Tindall And Cox

7 And 8, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C.2

1940 Printed In Great Britain

Initium sapientice timor Domini.

For a thousand years in Thy sight are but as yesterday when it is past, and as a watch in the night. — Psalm xc. 4.

Foreward

I should mislead readers were I to assure them that this book, written by an anatomist who has given half a century to the elucidation of the human body and by a surgeon who stands in the forefront of his profession, reads as easily as a work of fiction. Books which are fundamental in character are not easy reading, and this is a work of the kind. And yet the story which Dr. Gladstone unfolds is a romance. To trace the origin and evolution of the human pineal body or epiphysis, he has had to go back to an early stage of the world of life, one some 400 millions of years removed from us, when median as well as lateral eyes had appeared on the heads of our invertebrate ancestry. His search has not been confined to the geological record ; he has brought together from the literature of comparative anatomy and from his own observations what is known of median eyes and the pineal organ in all types of living forms, both invertebrate and vertebrate.

If Dr. Gladstone's story begins in a past which is very distant, that which Mr. Wakeley has to tell belongs to the present and the future. His story opens a new chapter in surgery, that which is to deal with the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the pineal body.

It is many years since Dr. Gladstone and I became students and friends at the University of Aberdeen, and friends and students we have remained ever since. We have in that time seen strange changes in the anatomy of the human body — structures such as the pituitary, thyroid, and adrenal, which we counted negligible, soar to positions of dominance ; we have seen parts of the brain such as the hypothalamus, which we regarded as mere wall-space of the third ventricle, become the seat of fundamental and vital processes ; and we have seen some structures dethroned. Although the " pineal gland " had fallen from its high estate long before Gladstone and I became students, it is of interest to compare the opinion which Descartes formed of it in the seventeenth century with the conclusions reached by our authors in the twentieth century.

Those who are familiar with The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy will recall Mr. Shandy's wish to discover " that part where the soul principally took up her residence." Let me quote from the original :

" Now from the best accounts he had been able to get of this matter, he was satisfied it could not be where Des Cartes had fixed it upon the top of the pineal gland of the brain, which, as he philosophized, formed a cushion for her about the size of a marrow pea ; this to speak the truth, as so many nerves did terminate all in that one place, it was no bad conjecture."

Readers will remember how Uncle Toby knocked the bottom out of Descartes' theory by relating the case " of a Walloon officer at the battle of Landen, who had one part of his brain shot away by a musket ball — and another part of it taken out after by a French surgeon, and after all, recovered and did his duty very well without it."

I need not anticipate the conclusions reached by our authors regarding the nature and function of the pineal body of the human brain ; they will be found in the concluding chapter of this book. In spite of all their labours, much remains enigmatic concerning the pineal body ; but they have laid a basis from which those who would go further must set out.

I must not be like a too loquacious chairman and abuse the privilege the authors have given me, in writing the foreword, by intruding my own opinions. Yet at the risk of sinning in this respect, there are one or two observations I have picked up in my recent reading, which seem to throw light on some of the problems discussed by them. There is first an observation made by Wislocki and King {Amer. Journ. Anat., 1936, 58, 421), who on injecting a solution of trypan blue in the live animal, found that it stained certain nuclear structures in the hypothalamus and also the cells of the pineal body — an outgrowth from the epithalamus. There are structural resemblances in the parts so stained. Such an observation fits easily into the final conclusions drawn by our authors. Hypothalamus and epithalamus, so widely separated by the thalamus in the human brain, were anciently close neighbours, both being associated with olfactory tracts and connections. Both are constituent parts of that cavity of the brain from which the lateral eyes as well as the median or parietal eye are developed.

Our authors find that the evidence which attributes a sex function to the pineal body is confused and contradictory, and rightly in my opinion bring in, on this head, a verdict of " unproven." Before we finally reject the evidence, however, it seems well to remember that through our retinae, there are transmitted to the brain not only stimuli which give rise to vision but also " light reflexes." It seems probable that the median as well as the lateral eyes had this double function. Through centres in the hypothalamus and pituitary, light reflexes can bear in upon the gonads and regulate their times of ripening. Prof. Le Gros Clark and his colleagues (Proc. Roy. Soc, 1939, 126 (B), 449) by cutting the optic nerves of the ferret and thus cutting off light reflexes, altered the onset of the period of heat. One can best explain the connection of the habenular ganglia of the pineal with the hypothalamus (through the striae medullares) by supposing that the median or parietal eye did exercise an influence on the hypothalamus and pituitary. Nor is it unreasonable to suppose that, in connection with sex-function, there arose in the basal part of the diverticulum which gives rise to the pineal organ an area or segment of nerve-cells, which, like certain groups in the hypothalamus, are neuro-secretory in nature. With the disappearance of the parietal eye in birds and mammals, this basal part embedded in the epithalamic system, persisted in them to form the pineal body.

I count it a privilege to have had the opportunity of reading this work while it was still in proof-form. I have learned much from it and I am sure others will benefit from its study as much as I have done. I would especially endorse a sentence in the first chapter, which reads :

" As one branch of medicine advances it becomes repeatedly necessary to fall back on the fundamental sciences for help and guidance, and realizing that the investigation of these pineal tumours proved rather barren some years ago, the authors determined to investigate the whole question of the nature of the pineal organ from the lowest to the highest forms in the animal kingdom."

By so doing they have shown themselves to be true disciples of John Hunter.

ARTHUR KEITH.

Buckston Browne Research Farm, Downe, Kent,

October 28th, 1939

Preface

This book is the outcome of a desire to study the pineal body from the broad standpoint of comparative anatomy, and to correlate as far as possible the structural appearance and connections of the mammalian epiphysis with the conflicting views which are held with regard to its origin and functions.

It was originally intended to deal with the subject mainly from the practical standpoints of diagnosis and operative technique, based upon the exact anatomical relations and connections of the pineal organ in the human subject. It soon became evident, however, that the study involved a much wider basis than the purely anatomical and clinical, and in order to assess the true significance of the facts which have been observed in connection with the mammalian epiphysis it would be necessary to investigate the history of the pineal body and parietal sense-organ from the standpoints of embryology, conparative anatomy, and geology. This, study raises further questions which are of great biological importance such as the influence which heredity appears to have in causing the retention for millions of years of an organ which in the majority of living vertebrate animals has completely lost its original function of a visual sense-organ ; also the problems that are raised by the recent hypothesis that the pineal body of the higher vertebrate classes is evolving as an endocrine organ by transformation of the vestigial parietal sense-organ into a gland of internal secretion, or the alternative supposition, that the mammalian epiphysis is a genetically distinct structure which has arisen independently of the parietal eye of fishes and reptiles. Another problem which has engaged the attention of previous investigators, and which we have discussed in the light of recent palaeontological work, is the explanation of the coexistence of a general similarity in structure of the pineal eyes of vertebrates and the median eyes of invertebrates along with certain differences in detail, which also exist, and which were formerly considered to exclude any possibility of the two systems being genetically connected. One of the first fruits of this inquiry was the definite confirmation which we found is afforded by palaeontology and comparative anatomy of the primarily bilateral origin of the parietal sense-organ ; and a second the conviction which was gained of the extreme antiquity of the pineal system — this seems not only to have evolved before the evolution of the roof-bones of the vault of the skull but in some types of primitive fish to have already entered the regressive phase of its ancestral history at the time when the dermal bones of the skull had first completely covered over the brain and formed a protective investment for the principal sense-organs, namely the olfactory, visual, and static.

The authors hope that the book will be of interest to readers outside as well as within the medical profession and that it will stimulate the study of other organs and systems of the human body from the standpoint of comparative anatomy, in addition to the purely practical aspect. We feel assured that the wider outlook which is gained by the investigation of any particular structure by the embryological and comparative methods well repays the additional time which is spent in acquiring this knowledge. It not only greatly increases interest in the particular organ which is being studied but it also gives a better insight into the special functions of the system both in health and disease.

Special care has been taken in selecting and making the illustrations, each of which has an independent explanatory legend. They have been assembled from various sources ; some are original drawings made specially for this work or which have previously been published by either one or both of us in the British Journal of Surgery, the Journal of Anatomy, or the Medical Press and Circular. Others have been reproduced from blocks, redrawn from lithographic plates, photographs, or drawings illustrating original papers, or from well-known standard works. The source of the latter has in each case been duly acknowledged, and the authors desire to take this opportunity of expressing their gratitude to the publishers and authors who have generously allowed us to make use of these figures ; and we desire specially to thank the publishers of those journals and books from which certain of the illustrations have been reproduced : John Wright and Sons, Bristol ; Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, London ; Quarterly Journal of the Microscopical Society, London ; Cambridge University Press ; Macmillan and Co., London ; Contributions to Embryology, John Hopkins University.

The authors also wish to acknowledge their indebtedness to the published works of all those writers whose names appear in the bibliography and in the following list. These works have been of the greatest value in determining the general trend of the book and an aid in coming to the conclusions which we have been enabled to draw from our own observations and experience. We wish especially to mention the names of the following authors : Achucarro, Agduhr, Ahlborn, Altmann, Amprino, Bailey, Badouin, de Beer, Beraneck, Berblinger, Bernard, Bertkau, Bourne, Brown, Cairns, Cajal, Calvet, Cambridge Natural History, Cameron, Cushing, Dandy, Dendy, Dimitrowa, Eycleshymer, Favaro, Foa, Gaskell, Globus, Goodrich, Grenacher, Harris, Haswell, Hill, C, Howell, Huxley, T., Huxley, J., Izawa, Kiaer, Kappers, Kerr, Kishinouye, Klinckostroem, Kolmer, Krabbe, Lang, Lankester, Leydig, Lereboullet, L'Hermitte, MacBride, MacCord, Marburg, Nicholson, Nowikoff, Parker, G. H., Parker and Haswell, Pastori, Patten, Penfield, Quast, Rio de Hortega, Schwalbe, Spencer, Stensio, Stormer, Strahl and Martin, Studnicka, Tilney and Warren, van Wagenen, Watson, Woodward, A. S., Zittel.

We desire, further, to gratefully acknowledge the help which we have received from Professor Doris L. MacKinnon of the Department of Zoology, King's College, London, and Dr. J. A. Hewitt, Lecturer on Physiology and Histology, King's College, London, for permission to make use of the specimens of Geotria and Sphenodon which belonged to the late Professor Arthur Dendy, and specimens from the Department of Histology from which some of the illustrations have been drawn. We also wish to thank Professors A. Smith Woodward, D. M. Watson, and W. T. Gordon, for valuable help with respect to references to literature, and Mr. Walpole Champneys and Margaret M. Gladstone for assistance in drawing some of the illustrations.

We also wish to express our thanks to Mr. E. J. Weston, Mr. Charles Biddolph, and Mr. Denys Kempson for the valuable assistance they have given in the preparation of serial sections of embryos and microphotographs. Lastly, we would like to thank Miss Mil ward Smith and Miss Mary Popham, who between them have typed the whole of the manuscript.

R. J. G. C. P. G. W.

London,

November, 1939

Contents

- Introduction

- Historical Sketch

- Types of Vertebrate and Invertebrate Eyes

- Eyes of Invertebrates : Coelenterates

- Flat worms

- Round worms

- Rotifers

- Molluscoida

- Echinoderms

- Annulata

- Arthropods

- Molluscs

- Eyes of Types which are intermediate between Vertebrates and Invertebrates

- Hemichorda

- Urochorda

- Cephalochorda

- The Pineal System of Vertebrates: Cyclostomes

- Fishes

- Amphibians

- Reptiles

- Birds

- Mammals

- Geological Evidence of Median Eyes in Vertebrates and Invertebrates

- Relation of the Median to the Lateral Eyes

- The Human Pineal Organ : Development and Histogenesis

- Structure of the Adult Organ

- Position and Anatomical Relations of the Adult Pineal Organ

- Function of the Pineal Body

- Pathology of Pineal Tumours

- Symptomatology and Diagnosis of Pineal Tumours

- Treatment, including the Surgical Approach to the Pineal Organ, and its Removal: Operative Technique

- Clinical Cases

- General Conclusions