Paper - The pharyngeal pouches and their derivatives in the mammalia

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Fox H. The pharyngeal pouches and their derivatives in the mammalia. (1908) Amer. J Anat. 8(3): 187-250.

| Online Editor |

|---|

| Note this paper was published in 1908 and our understanding of pharyngeal arch pouch derivatives has improved since this historic study using cat, pig and rabbit embryos.

|

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

The Pharyngeal Pouches and their Derivatives in the Mammalia

By Henry Fox, Ph.D.

With 73 Figures.

Introduction

The present paper is an outgrowth of an earlier unpublished article submitted to the Faculty of the University of Pennsylvania in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. The original article gave the results of a study of six or seven different stages in the development of the pig. Subsequently, through the kindness of Dr. C. S. Minot, I was enabled to study the extensive series of mammalian embryos in the collection of the Harvard Medical School. Of these I studied most thoroughly the series of pigs and cats, but also gave some attention to the later stages in the rabbit. The results of this additional study, along with those included in my former article, I now offer in the present paper. My aim is to give a complete history of the pharnygeal pouches and their derivatives as typically exemplified in the mammalia. The main facts of this history had been largely determined previous to my starting the investigation, but the interpretations attached to these facts by various authors differed considerably, and, moreover, there remained a number of details about which there was much confusion. These unsettled matters seemed to me to warrant a full investigation of the subject.

Soon after I had begun my observations an important article by Hammar appeared treating of the development of the fore-gut in man. Hammar had in his possession a large series of embryos, and from these he made out a full and consistent history of the middle ear and Eustachian tube. He also compared with his own results the statements made by earlier authors, and, through the more abundant material at his command, was enabled to show how their conclusions were in most cases the result of mistaken interpretation based on an insufficient body of facts.

While primarily concerned with the development of the pharynx in man, Hammar also examined a series of rabbit embryos, and while he does not in his article treat of them particularly, he yet mentions that he finds an essential agreement in the formation of homologous parts in both forms. Accordingly, he is inclined to assume that the essential features of the development in man will hold good in the case of other mammals.

Hammar’s first article was followed by a second on the fate of the second pharyngeal pouch. This is the last article of his I have seen, and, so far as I know, he has not published any articles on the fate or the last two pouches.

The appearance of Hammar’s paper seemed to me at first to do away with the necessity of further study of the first two pairs of pouches, but as Gaupp had already expressed the idea—based upon the conflicting statements of earlier investigators——that the formation of these parts probably differed considerably in different species of mammals, I concluded that a further contribution on the subject in the three species examined by me would not be without value. Moreover, as Kastschenko, the chief authority on the process in the pig, had declared that the middle ear tube did not arise in any way from the first pharyngeal pouch, I considered this an additional reason for continuing my investigation.

The results of this investigation, so far as the first and second pharyngeal pouches are concerned, are largely confirmatory of the conclusions reached by Hammar in man and the rabbit. The probability therefore is that the development of these parts is essentially similar in the majority of placental mammalia.

In the case of the third and fourth pharyngeal pouches I have obtained results which clear up certain details about which there has been much confiict of opinion. Among these may be mentioned the determination of the origin and structure of the carotid gland, a reconciliation of the confiicting statements regarding this structure made by Kastschenko and Prenant, a confirmation of the ectodermal origin of the so—called thymus superficialis of Kastschenko, and finally the origin of a second structure—beyond doubt the glandule thyroidienne of Prenant—from the fourth pouch.

My earlier studies were made by the aid of the wax reconstruction method. Later, owing to the lack of facilities for continuing the use of this method, I adopted the method of graphic projection, making dorsal, ventral and lateral views of each stage studied. The Pharyngeal Pouches in the Mamnialia 189 During the progress of this investigation I received much assistance from a number of investigators. To Dr. E. G. Conklin I am greatly indebted for his kind encouragement and helpful suggestions, and for these I desire to express my hearty thanks. To Dr. C. S. Minot I am under special obligations for his kindness in allowing me to examine the fine series of embryos in his charge. I also desire to thank Dr. C. B. Davenport for permission to continue part of this work in the laboratory at Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island.

I shall present the results of my studies under the following headings:

- The Formation and Structure of the Pharnygeal Pouches.

- The Later Modifications and Fate of the Pharnygeal Pouches.

In this study I was enabled to examine the following stages, which I here present in the order of progressive development:

(3) 6.5 mm., (M?) (1) 4.6 mm., N0. 398 (13) 14 days, 10.0 mm., No. 157 (6) 9.0 mm., (M5) (2) “ 413 (19) 16% “ 17.8 mm., “ 576 (7) 10.0 111111., No. 401 (4) 6.2 mm., “ 380 (20) 18 “ (8) 12.0 mm., “ 518 (5) 9.7 mm., “ 446 (25) 20 “ 29.0 mm., “ 172 (9) 13.5 mm., (14) 10.7 mm., “ 4:74 (26) 21 “ (10) 14.0 mm., N0. 65 (16) 15.0 mm., “ 436 (11) 17.0 mm., “ 51 (21) 23.0 mm., “ 466 (12) 18.0 mm., (M3) (24) 31.0 mm., “ 500 (15) 20.0 mm., No. 542 (17) 24.0 mm., “ 64 (18) 25.0 mm., (M4) (22) 32.0 mm., N0. 74 (23) 35.0 mm., (M)

1. The Formation and Structure of the Pharyngeal Pouches

Under this heading I shall describe all stages leading up to the complete formation of the four pairs of pharyngeal pouches characteristic of the mammalian embryo. The stages here considered include Nos. 1 to 4, inclusive.

The earliest stage of development of the pharynx and its appendages was shown in a cat embryo of 4.6 mm., No. 398 of the Harvard collection (figs. 55 and 56.) The embryo is approximately straight, the headfold is distinctly differentiated, but the posterior two-thirds of the enteric cavity opens widely into the yolk vesicle (at x in the figures). The neural tube is closed except anteriorly, where a narrow cleft still persists. The optic vesicles are present, but there is no sign of the optic cups. The pharynx anteriorly is in contact with the stomatodeal plate (St.). As a whole it is a relatively wide, dorso-ventrally flattened sac. Only two pairs of pharyngeal pouches are present as wide lateral diverticula of the pharynx. Of these the first (Ph. P. I) alone reaches the ectoderm and joins with it for a short distance. The second pair (P11. P. 2) are only barely indicated as faint outbulgings, the one on the left being the more distinct of the two.

The pericardium is of small size, in striking contrast to the enormous bulk it attains in later stages. It contains the inner portions of the great vitelline veins (V. v.), which are joined together only at their extreme anterior ends. Only one pair of fully developed aortic arches is present—the first or mandibular (ao. i). These extend dorsally in front of the first pouch and join the paired dorsal aortas. Two prominent out—bulgings from the sides of the vitelline veins are probably destined to form the common trunk from which the remaining aortic arches subsequently arise. ' A cat embryo, No. 413 of the Harvard collection, shows the next stage in advance (fig. 5'7). The posterior part of the body is still approximately straight, but the head portion is strongly flexed upon‘ it and is of relatively much greater extent than before.

Anteriorly the stomatodeal plate has disappeared. The pharynx is, as before, a wide flattened sac, but its width in its anterior portion is somewhat greater than in its posterior part. Its floor is somewhat deeper than before and close to the mouth is produced into a deep median groove— the median oral groove GR).

The hypophysis (HYP) appears as a blunt protuberance from the dorsal side of the pharynx close to its anterior extremity. Three pairs of pharyngeal pouches are now present. The first two pairs reach the ectoderm and join with it for a considerable extent (see light areas of Ph. P. 1 and 2, fig. 57). Of the third pair, the pouch on the right side reaches the octoderm, While that on the left is still removed by a slight interval from it. _ The first pharyngeal pouch forms a relatively large transverse fold. The greater part of its lateral margin is in contact with the ectoderm. The area of contact is widest dorsally and diminishes progressively in width toward the ventral side. The extreme ventral part of this margin extends a slight distance below the region of contact as a free edge, which then turns suddenly inwards as the ventral margin of the pouch. This part of the pouch projects slightly below the floor of the pharynx and thus forms a ventral diverticulum of the pouch. The second pharyngeal pouch, although considerably smaller than the first, is essentially similar to it. It has a ventral diverticulum, which is somewhat less prominent than the same part in the first pouch.

The third pharyngeal pouch is considerably smaller than its two predecessors. It forms a finger—like outgrowth, which extends outwards and downwards and, in the case of that on the right side, joins the ectoderm. The left pouch does not quite reach the latter.

The fourth pharyngeal pouch is only barely indicated by a slight bulging of the walls of the pharynx behind the base of the third pouch.

The first three pairs of aortic arches are now fully developed and a fourth is beginning to develop. _ In a pig embryo of 6.5 mm. (M2 of my collection) and a cat of 6.2 mm. (No. 380, Harvard collection) all the pharyngeal pouches and their associated parts are typically developed. The two embryos show almost the same relative stage of development, but that of the pig shows a slightly more primitive condition. It will, accordingly, be considered first.

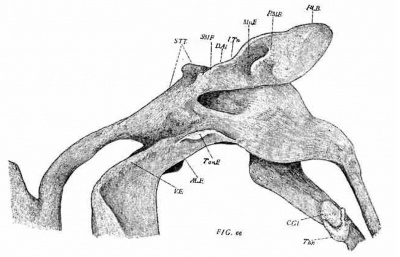

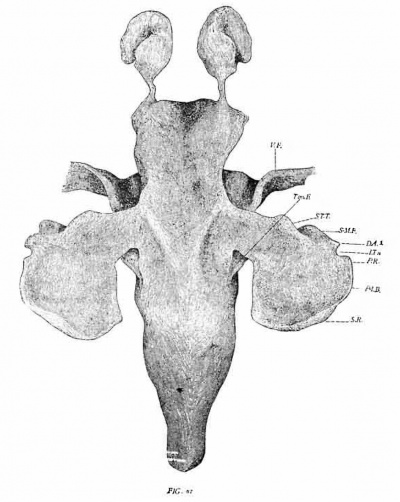

The pharynx (figs. 1, 2 and 3) shows four complete pairs of pharyngeal pouches, all of which have a more or less extensive contact with the ectoderm of the corresponding grooves. Between the first two pairs of pouches the pharynx is considerably wider than in the region between the last two pairs. Anteriorly the hypophysis (HYP.) projects forward as a blunt protuberance, and immediately back of it arises a minute conical process, the representative of Seessel’s pocket.

The pharyngeal pouches in general have the form of vertical winglike expansions projecting outwards and slightly backwards from the side walls of the pharynx. Typically, they are joined to the pharynx by a relatively narrow base and only laterally dilate into the wing-like expansions mentioned. Each pouch is attached laterally to the ectoderrn. The extent of this attachment is shown by the clear areas in fig. 1. As these show, it varies greatly, being most extensive in the second, where it includes almost the entire lateral margin. A similar relation is noted by I-Iammar in the corresponding stage in man, and, as the figures of the next stage show (see fig. 58), it holds in the cat.

A conspicuous feature—shown best in the second and third pouches—is the presence of deep ventral projections to the pouches (V.D. 1-4). They reach to a greater or less extent below the floor of _the pharynx. Hammar calls them the ventral diverticula. They appear, from all published figures examined, to be constant at the corresponding stage in all mammals so far investigated. A ventral view (fig. 3) shows a number of important features. Projecting from each side of the pharynx are the four pharyngeal pouches, each with its ventral diverticulum. That of the first pouch (V. D. 1) fOI‘1II3S a low narrow ridge extending from the infero-lateral angle of the pouch inwards and slightly backwards quite to the median line, where it joins the corresponding ridge of the opposite side. There is thus formed a complete transverse V-shaped fold, the apex of the fold being the meeting point of the two opposite limbs. The ridge corresponding to the median oral groove begins immediately in front of this apex. The shallow impression between corresponds to the tuber~ culum impar of His. Just behind the apex is the median thyroid. The latter consists of two lobules joined to each other and to the pharynx by a slender epithelioid cord.

The ventral diverticula of the next two pouches are much deeper than that of the first, but are largely confined to the lateral half of the pharynx. A faint ridge, however, extends from the base of the second diverticulum to the median line, where it is joined by a similar ridge from the third pouch (see fig. 60 of the next series for this condition). The two sets of ridges thus converge to form a rather low protuberance immediately above the thyroid and in front of the tracheal ridge.

The presence of these inner low ridges connecting the opposite ventral diverticula of the second and third pouches shows their essential agreement in this respect with the first pouch. Only, in the case of the two former, the lateral half of each ridge is produced far below the level of the inner portion, while in the first pouch the depth (its height) of the ridge is throughout approximately uniform.

Owing to the form of the ventral diverticula of the second and third pouches there is left between their opposite lateral halves a considerable space, in which is lodged the apical portion of the heart along with the large arteries radiating from it (fig. 3). The prominent aortic arches at this time are the third (carotid), fourth (aorta typica) and the fifth (pulmonary). The latter has a small posteriorly directed braneh—the later pulmonary artery (fig. 3, Pul.), The first aortic arch is much reduced in size and has lost all connection with the dorsal aorta. The second is also extremely reduced and is only connected with the dorsal aorta by an extremely narrow (apparently functionless) vessel.

Immediately back of the common origin of the aortic arches begins a sharp median ridge, which deepens posteriorly. It represents the future larynx and trachea. The first pharyngeal pouch has a greater lateral extent than any of the succeeding. As the figures show, the lateral extension of the pouches decreases regularly from before backwards. The first pouch blends with the lateral portion of the pharynx by a broad base, so that it is impossible to draw any definite line between the two. The limits assigned by Hammar, whose usage in this matter I adopt, will be given presently. Laterally the outer extremity of the pouch is produced upwards as‘ a blunt prominence——the dorsal diverticulum of I-Iammar—which projects considerably above the roof of the pharynx. The dorsal-diverticulum terminates in a narrow apex—the dorsal apex (d. a. 1) (Recessus tympani anterior, Hammar).

Hammar includes in the first pouch the following parts: (1) The sulcus tubo-tympanicum. This is Mo1denhauer’s term for the prominent ridge (fig. 2, S. T. T.) representing the antero—lateral border of the pouch. It begins externally at the dorsal apex and extends downwards, inwards and forwards, terminating close to the base of the hypophysis. (2) The latero-ventral ridge and its continuation, the ventral diverticulum. This is a narrow ridge which in its dorso-lateral portion is joined to the ectoderm. The connection includes the dorsal two-thirds of its lateral extent. The lower third forms a free edge, and this, at its lower outer angle, turns sharply inwards and backwards to form the ventral diverticulum. (3) The sulcus tensoris tympani (S. T. Ty.). This is a term applied. by Hammar to the border extending from the dorsal apex backwards and inwards to join the next part along the inner border of the hyoid arch. (4) The sulcus tympanicus posterior (S. T. P.). This term, also given by Hammar, includes the longitudinal ridge forming the inner boundary of the hyoid arch arid connecting the sulcus tensoris tympani with the base of the second‘ pouch. (5) The impressio cochlearis. This I-Iarnmar defines as a conspicuous depression on the dorsal wall of the pouch close to its origin from the pharynx. The auditory sac lies immediately above this area.

The second pharyngeal pouch is characterized, as already mentioned, by the extensive contact of its lateral margin with the ectoderm. Only at its extreme lower end does this border have a free margin. So far as the present specimen is concerned, there is no communication between the lumen of the pouch and the exterior. The closing membrane is exceedingly thin, but examination shows no break in its continuity.

The ventral diverticulum of this pouch forms a. prominent quadrangular folcl. The mesial half forms only a faint ridge, but the lateral portion is very deep. The deepest part is represented by the blunt angle immediately below the lower end of the lateral border.

Posterior to the region of the second pouch the pharynx diminishes considerably in width. Its lateral margin forms a low ridge connecting the second pouch with the third. Between this ridge and the median dorsal ridge of the pharynx is a shallow longitudinal furrow, in which is lodged the dorsal aorta.

The third pharyngeal pouch is slightly smaller than the second. It is joined by a relatively narrow base with the pharynx, but distally expands into a broad wing—like fold with a prominent ventral divertic- \ ulum. A slight dorsal diverticulum is also present. The lateral margin is in contact with the ectoderm for almost its entire length.

As in the case of the second pouch, the deep portion of the ventral diverticulum is limited to the lateral half of the pharynx. Its mesial portion is represented by a low ridge, which extends from the root of the lateral half forwards and inwards close to the median line, where it joins with the same part of the second pouch. The extreme ventral tip of the ventral diverticulum is turned toward the mesial side.

The fourth pharyngeal pouch is the smallest of the series. It is divided by a shallow constriction into two parts, a dorso-posterior portion (Ph. P. IV), which projects laterally and at one point comes into contact with the ectoderm, and a ventro-anterior bulge, which terminates blindly and corresponds to a ventral diverticulum.

From the base of the ventral diverticulum a low ridge extends forwards to the base of the third pouch. It corresponds to the mesial extension of the ventral diverticulurn.

In the cat embryo of 6.22 mm. (No. 480, Harvard collection) the condition of the pharynx is essentially similar to that just described in the pig. As in the latter, four pairs of pharyngeal pouches are present.

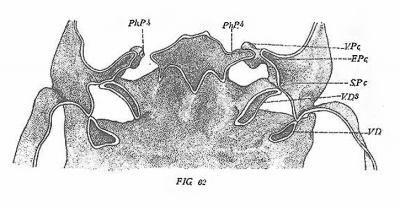

The characteristic features of this stage are shown in figs. 58, 59 and 60. fig. 58 shows the lateral aspect. The clear areas on the lateral margins of the pouches show the extent to which these are attached to the ectoderm. It will be noticed that they are essentially similar to the same parts in the preceding specimen. The dorsal diverticulum of the first pouch is somewhat more elevated. The ventral diverticulum of the third pouch extends to a slightly lower. level. The fourth pouch shows more clearly its division into two portions. The dorso-posterior portion is somewhat bulbous. Its more dorsal part is flattened and is produced outwards as a thin process which reaches the ectoderm. The ventral diverticulum projects almost directly forwards.

The median thyroid is of a relatively large size. It has lost all connection with the pharynx and lies at a lower level than in the preceding specimen.

Owing to the more rapid growth of the mandibular and hyoid arches as compared with that of the arches posterior to them, the originally almost transverse plane of the second and third pouches becomes postero-lateral. Their originally anterior and posterior surfaces thus become antero—lateral and postero-internal, respectively. Their lateral margins thus come to project backwards.

The increased antero-posterior growth of the mandibular arch leads to a change in the direction of the tubo—tympanal border of the first pouch. The latter is at first almost transverse, but later assumes a more anterior direction. The more antero-mesial direction of this border in the present stage as compared with that in the preceding shows the beginning of the change. As growth continues the border progressively lengthens, thus giving an increased width to the basal portion of the pouch. These relations are clearly indicated in the dorsal view (fig. 59).

figs. 59 and 60 show the relations of the more posterior pouches to the now fully formed sinus praecervicalis—relations which are of considerable importance in view of later developments. Owing to the great increase in bulk of the hyoid arch the posterior border of the latter projects backwards. The third and fourth arches increase but slightly in bulk and thus remain at a considerably lower level than the arches in front. The sinus is thereby formed as a deep recess, the bottom being formed by the arches mentioned. Just within the anterior margin of the sinus opens the second pharyngeal groove. The third groove occupies the middle of the inner walls. Dorsally it meets the upper extremity of the fourth groove. From this point the latter turns strongly downwards, backwards and inwards to where it meets the fourth pouch. As the latter lies at a considerably lower level than the other pouches, this part of the sinus projects inwards as a prominent, pointed process.

The ventral view (fig. 60) shows some additional features. On the right side the section is taken at a slightly lower level than on the opposite side, and accordingly it shows the entire exterior of the first two arches, together with the ventral extension of the first pharyngeal groove. It also shows how the antero-internal angle of the sinus praecer— vicalis is continued ventrally into the ventral extension of the second groove. The latter has a decided anterior course, and at its mesial end meets the first groove.

On the left side the ventral wall of the sinus praecervicalis is represented as having been removed, so that its interior is clearly shown. The internal process of the sinus is less deep than the same part on the right.

The continuous transverse fold formed by the ventral diverticula of the first pouch is clearly shown in this view. As in the case of the pig, there is no contact between this fold and the corresponding ventral extension of the groove, the two being separated by a considerable thickness of mesenchyrne.

II. The Later Modifications and Fate of the Pharyngeal Pouches

Owing to the more or less independent course which the different pouches take in their later history, I think it will conduce to greater clearness if I consider them separately, and accordingly I subdivide the above topic as follows:

A. The Modifications of the first Pharyngeal Pouch.

- (a’) The Formation of the Primary Tympanic Pouch.

- (a”) The Differentiation of the Tympanic Cavity and Eustachian Tube.

B. The Modifications and Fate of the Second Pharyngeal Pouch.

- (b’) The Retrogressive Modifications of the Pouch.

- (b”) The Formation of the Tonsillar Fold.

C. The Metamorphoses of the Third Pharyngeal Pouch and its Derivatives.

- (c') The Elongation of the Ventral Diverticulum and the Formation of the Thymus.

- (c”) The Origin and Structure of the Carotid Gland.

- (c’”) The Sinus Praecervicalis and its Relation to the Thymus.

D. The Fourth Pharyngeal Pouch and its Transformation into the Lateral Thyroid and Glandule Thyroidienne.

A. The Modifications of the First Pharyngeal Pouch

(a’) The Formation of the Primary Tympanic Pouch

The pharynx is essentially alike in a pig of 9 mm. (Series M5, my collection) and in a eat of 9.’? mm. (No. 446, Harvard series). fig. 61 gives a ventral View in the latter. The first pharyngeal pouch is wider in the antero—poste1'ior direction than before——a change connected witlr the anterior growth and elongation of the oral cavity and the consequent prolongation in the same direction of the attached tubo-tympanal rim. The ventral diverticula are slightly less prominent. T0gether they form a low V—shaped elevation on the floor of the pharynx. Just external to the median apex formed by the convergence of the arms of the V each is joined by one of the pair of folds forming the outer line of the tuberculum impar (Tub.) . Close to the lateral margin each arm is crossed by the broad alveolo-lingual fold (AL.F.). A slight distance in front the latter meets the vestibular fold (V.F.). Immediately back of the point of convergence a lateral fold (SM is given off, which extends obliquely outwards and backwards over the lateral ridge of the latter. The formation of this fold marks the initial step in the development of the later important submeckelian fold.

The tuberculum impar arises as a result of the bipartition of the median oral ridge. The crest of the latter widens and its middle part then becomes depressed to form a shallow concavity—the ventral counterpart of the tuberculum.

In the pig of 10 mm. (No. 401, Harvard series, figs. 4-6) the pouch is joined to the ectoderm by only the dorsal third of its lateral ridge. The remainder of this border is now free and forms a low fold separating the antero-lateral and postero-lateral surfaces of the pouch. Ventrally it is continuous with the ventral diverticulum. Where the transition takes place the alveolo-lingual swelling cuts across it at right angles, forming here the line of demarcation between the pouch and the pharynx.

The ventral cliverticula present no new points of interest. The swellings which marked the lateral boundaries of the tuberculum impar are now relatively inconspicuous, having been absorbed along with the adjacent parts of the pharyngeal floor in the broad depression (representing the anlage of the tongue) lying between the alveola—lingual ridges.

Dorsally the pouch projects relatively higher than hitherto and terminates in a more acute apex. This condition is not due to the growth dorsalwards of the pouch, but is a result of a ventral displacement of the pharynx. As a comparison of the figures shows, the formation of the neck of the animal is attended with a ventral (caudal) fiexure of the posterior half of the pharynx. The flexure also afiects to a minor degree the remainder of the pharynx, tending to displace it to a lower level. This tendency, however, is checked by the fact that the first pair of pouches is still attached to the ectoderm by their lateral extremities. These points are accordingly relatively fixed in position, and, as the basal portion of the pouch sinks in response to the general lowering of the pharynx, the structure attains the pronounced ascending course characteristic of it at this stage.

In consequence of this change the basal portion of the pouch has assumed an almost horizontal plane, while its peripheral part ascends almost vertically. Where the two parts meet there is on the lateral surface a slight ridge extending from the lateral ridge to the base of the vestibular fold. It corresponds with the fold mentioned in the preceding stage as forming the beginning of the submeckelian fold (fig. 6, S.M.F.).

This fold subdivides the antero-lateral wall into two surfaces, an external, dorso—lateral and a mesial ventro—lateral surface. The former forms an elongated triangular area limited dorsally by the tubetympanal crest and posteriorly by the lateral ridge. The latter forms a smaller triangle bounded internally by the alveolo-lingual fold and posteriorly by the lateral ridge.

The anterior prolongation of the tubo-tyrnpanal ridge is more pronounced than in the preceding stage. The difference is due to a continuance of the process, already mentioned, of anterior elongation of the oral cavity.

A pig of 12 mm. (No. 518, Harvard series, figs. 9-11) shows the pharynx only slightly larger than in the stage just descr_ibed. The continued anterior elongation of the oral cavity has given the tubetympanal crest a decided antero-posterior course. The pouch retains its connection with the ectoderm only at its dorsal apex. The lateral ridge forms only a low prominence extending from the dorsal apex to the ventral diverticulum.

The dorsal apex appears broader and more depressed than in the preceding stage. This condition, I think, results from the lateral flex ure of the apex in consequence of the general growth in width of the head.

At this stage the pouch has the essential features of the primary tympanic pouch of Kastschenko. This investigator considered the pouch as merely a widened diverticulum of the lateral wall of the pharynx and regarded the lateral ridge as alone representing the first pharyngeal pouch. As Hammar shows and my observations confirm, Kastschenko’s conception of the pouch was entirely too limited and was doubtless due to his not examining earlier stages in which it is more typically developed.

The primary tympanic pouch at this stage is a dorso—ventrally flattened triangular fold which arises by a broad base from the pharynx and terminates peripherally in the dorsal apex. The pouch as a whole lies almost horizontally, but towards the lateral edge it turns sharply upwards. Its walls are medic-dorsal and lateral. The former is limited laterally by the tubo-tympanal crest, dorsal apex and posterior tympanal borders. All below these limits is embraced in the lateral wall. This is divided by the lateral ridge into two surfaces, antero-lateral and latero—posterior. The antero-lateral surface is further subdivided into two areas—dorso—lateral and ventro—lateral—by the submeckelian fold.

The ventral diverticula now form a pair of low swellings. Mesially they are interrupted by a shallow longitudinal groove connecting the tongue concavity with the deep hollow in front of the larynx.

In a pig of 13.5 mm. (Series M1 of my collection) the condition of the pouch is intermediate between that last described and the next. The only feature that calls for remark is the presence at the dorsal apex of a short narrow process by which the pouch retains its last connection with the ectoderm (fig. 3'7).

In the pig of 14 mm. (No. 65, Harvard series, figs. 14-16) the primary tympanic pouch has separated entirely from the ectoderm and now lies some distance below it-—a condition due to the greater lateral growth of the head compared with that of the pouch.

The pharynx at thistime begins to show modifications due to its own differential growth. The increase in width of the anterior half is considerably greater than in the posterior portion. Thus, while the distance between the apices of the first pair of pouches has increased appreciably since the last stage, that between the same parts in the second pair remains approximately the same. In consequence of this the pouch now shows a more pronounced lateral projection. The tensortympani crest turns sharply inwards and joins the posterior tympanal border at an obtuse angle. The latter border also shows a tendency to assume a more transverse trend. The second pouch appears as a rounded prominence at the postero-internal angle of the tympanic pouch.

The ventral half of the lateral ridge and its continuation, the ventral diverticulum, have disappeared. Their former position is only indistinctly indicated by low swellings on the under side of both pouch and pharynx. The dorsal half of the lateral ridge, however, is continued into the submeckelian fold, and these are now slightly more prominent, Together they now form a continuous crescent—shaped fold extending from the dorsal apex to the base of the vestibular fold. It underlies, for the greater part of its length, l\Ieckel’s cartilage. For this reason I have called it the submeckelian fold. The shallow depression in the lateral wall which it subtends I call the Meckelian fossa.

The paired ridges which formerly limited the tuberculum impar laterally have now become blended with the epithelium covering the tongue anlage. The formation of the latter has been accompanied by the progressive downgrowth of the surrounding alveolo-lingual crests, particularly in their anterior portion. The deep space thus enclosed is filled with the tissues of the organ. Posteriorly this space is now connected by a deep groove with the space in front of the larynx.

An early stage in the formation of the external auditory meatus is shown by the conical indentation projecting under the pouch. Its inner angle terminates a short distance below the latero—posterior surface. The two structures are nowhere in contact, a moderately thick layer of mesenchyme intervening between them.

In the pig of 1*?’ mm. (No. 51, Harvard series, figs. 19-21) the primary tympanic pouch is slightly more expanded and depressed. The dorsal apex has become flattened out to a low rounded prominence and has sunken to a lower level, so that it scarcely projects above the level of the pharyngeal roof. The tubo-tympanal crest in consequence is almost horizontal. Anteriorly it turns sharply inwards to form the relatively short tubal portion, the remainder forming the tympanic part (see fig. 20).

On the lateral wall the submeckelian fold forms a prominent, projecting ridge. It extends from the dorsal apex downwards and forwards to the latero—inferior edge, when it projects as a convex ventral pocket. In front of this region it suddenly dies out, forming only a low fold (fig. 19, 37.), continued to the base of the vestibular fold. The interval outside of this part is occupied by Meckel’s cartilage. The latter ascends from the mandibular arch in the angle between the submeckelian and the vestibular folds and thereby comes to lie in front of and above the former. The presence of the cartilage in the angle mentioned has probably some close connection with the separation of the two folds. Its presence would inhibit continued lateral extension of the connecting portion, while it would not interfere with such growth in the remainder of the fold. The latter would then continue to expand laterally and would thus give rise to the prominent projection which it forms at this stage.

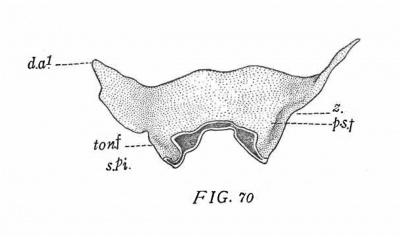

The form of the pharynx is essentially the same in a pig of 18 mm. (Series M3, my collection) and a rabbit of 14 days (No. 157, Harvard series, fig. 70). It differs but slightly from that last described. The greater part of the tympanic pouch lies in an almost horizontal plane, only its extreme lateral portion being slightly upturned (figs. 41-46). The dorsal apex forms only a low eminence, the meeting point of tubetympanal border, submeckelian fold and tensor tympani border.

The most important feature of this stage consists in the definite segregation of the neighboring skeletal structures, particulary l\Z[eckel’s cartilage and the auditory capsule. Their formation is so intimately associated with certain later modifications of the pouch that a short description of their essential characteristics is necessary. Meckel’s cartilage is a stout rod, which, as already mentioned, rises from the mandibular arch in the angle between the submeckelian and vestibular folds and then turns obliquely backwards above the former fold (figs. 41-43). Close to the posterior margin of the fold it sends down the stout manubrium which curves around the back of the fold and terminates in a slight depression——the manubrial fossa—immediately beneath (figs. 43-44). The submeckelian fold is thus wedged in the angle between Meckel’s cartilage and the manubrium and is thus relatively fixed in position (fig. 43). This relative fixity of the fold is an important factor in the final transformation of the pouch into the definitive tympanic pouch and Eustachian tube.

The auditory capsule occupies the depression (Impressio cochlearis) between the dorso-internal surface of the pouch and the roof of the pharynx.

(a”) The Differentiation of the Tympanic Pouch and Eustachian Tube

In a pig of 20 mm. (No. 542, Harvard series, figs. 23-27) we observe the beginning of the changes leading to the final transformation of the primary tympanic pouch into the definitive pouch and Eustachian tube. The transformation appears to be closely connected with a continuance of the processes already indicated. Of these We may recall (1) the ventral (caudal) flexure and elongation of the posterior half of the pharynx in connection with the formation of the neck, (2) the anterior extension and fiexure of the mouth, and (3) the relative fixation of the primary tympanic pouch by the differentiation of the surrounding cartilages.

As a result of the iiexures of the pharynx and mouth the common structure now has the form of an arch (fig. 23), the apex of the arch being that part lying between the primary tympanic pouches. From the side of this part each pouch projects as a broad, flattened fold, which towards its periphery turns strongly upwards so that the apex again extends some distance above the roof of the pharynx. Together the tub0—tympanal and tensor tympani borders form an arched curve, the apex being formed by the dorsal apex (fig. 23). The submeckelian fold (S-ELF.) has much the same appearance as before. It is completely separated from the vestibular fold. It, however, no longer projects below the ventral line of the pouch, but lies a slight distance above it on the lateral surface. This change has been eifected by a process which only becomes noticeable in the region of the pouch at this time. This is the downward growth and posterior extension of the alveolo-lingual folds As these grow down they carry with them the adjacent ventro-lateral wall of the pouch, and thus the latter loses its original horizontality and assumes an inclined position. Its surface thus comes to be more nearly continuous with the plane of the dorso-lateral portion. Since the submeckelian fold forms the dividing line between the two portions, it comes, in consequence of this change, to occupy its present relatively higher level on the side of the pouch.

An important, but at this stage inconspicuous, feature is a shallow indentation on the posterior tympanal rim between it and the second pouch (see figs. 2-6-27, z.). The latter pouch is now so small that the exact line of demarcation is not easily recognizable. A slight ridge (fig. 26, p-m.f.), however, which extends from the indentation to the submeckelian fold, enables one to fix upon this point as being between the two structures. The same ridge, showing the same relations, is present in the immediately «preceding stage when the second pouch was still clearly recognizable. This ridge later becomes the prominent elevation limiting the manubrial fossa posteriorly.

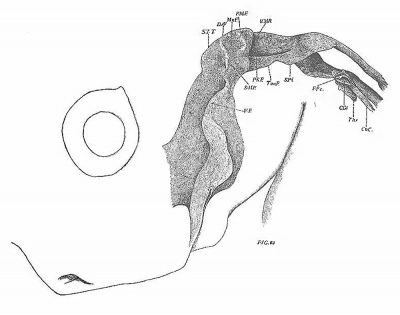

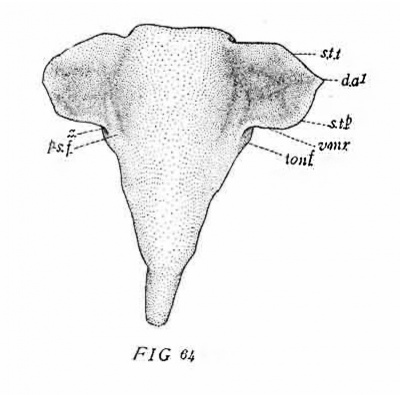

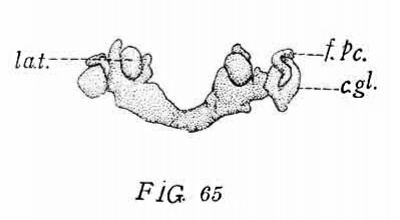

In the cat of 10.7 mm. (No. 474, Harvard series) the tympanic pouch shows a slight advance. The indentation between the pouch and the second pouch is slightly deeper and consequently the posterior tympanal crest now forms a rounded lobe projecting dorsally. In all other respects this stage is so similar to the preceding that further description is unnecessary. The l?haryngeal Pouches in the Mammalia 203 The eat of 15 mm. (No. 436, Harvard series, fig. 63, 64) presents the next stage in the modification of the tympanic pouch. The incision, which in the preceding stages had just begun to form between the tympanic pouch and the dorsum of the second pouch, is now much deeper. The postero-lateral lobe of the pouch in consequence protrudes more\ strongly in the dorso-posterior direction. As a result of the incision a new ventro-mesial border (V.M.R.) has begun to form between the base of the pouch and the pharynx. Posteriorly this border connects by a rounded angle with the posterior tympanal border (fig. 64, s. t. p.). 6 The connection of the pouch with the pharynx is both relatively and actually of lesser extent than in the preceding stages. This condition represents the commencement of the gradual constriction of the connecting part as a result of the anterior extension of the incision.

Owing to the increased depth of the intervening incision the tympanic pouch is now completely separated from the second pouch. This condition is apparently produced in the following manner: It will be recalled that the pouch has now become relatively fixed in position by being included between Mecke1’s cartilage with its manubrial process and the auditory capsule. The neighboring lateral walls of the pharynx, on the other hand, are continuously being displaced to a. lower level by the downgrowth of the alveolo-lingual margins. Among the parts thus carried down is the concavo-convex fold representing the dorsal remnant of the second pouch (Ton.F.). In consequence of this displacement of the second pouch and the relative flxity of the tympanic pouch, the incision (z) between the two spreads dorsally over the second pouch and reaches the longitudinal ridge (P—S.F.) lying immediately internal to the base of the pouch (cf. figs. 26, '70 and 64). Thus the base of the tympanic pouch is placed in connection with this ridge, which is the external expression of the groove extending backward from the Eustachian opening between the levator cushion and the salpingo-pharyngeal fold. For convenience in description I shall speak of it as the post-salpingeal groove.

As a result of the process. just described the dorsum of the second pouch comes to lie on the lateral surface of the pharynx below the posterior margin of the tympanic pouch. With the subsequent downgrowth of the a.lveolo-lingual folds it is carried farther ventralwards, and, as will be described later, is finally transformed into the tonsillar recess. On the expanded lateral wall of the tympanic pouch two prominent outstanding folds are now present. The anterior is the submeckelian fold; it shows the now deep Meckelian fossa on its dorsal side. The posterior fold is less prominent; it corresponds to the ridge formerly mentioned as forming the posterior limit of the manubrial fossa. The latter now forms a depression of considerable depth.

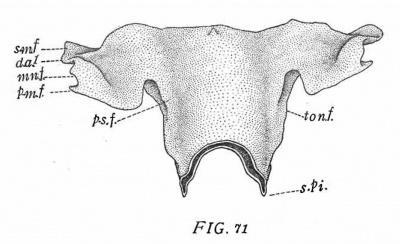

A rabbit of 161/2 days, 17.8 mm. (No. 576, Harvard series, fig. '71) shows the constriction of the tympanic pouch still further progressed. The post-salpingeal fold (p. s. f.) is more convex. The dorsum of the second pouch (ton. f.) is separated by a short interval from the base of the tympanic pouch. The remaining features of the pouch are essentially like those in the following stage.

This stage is represented by a pig of 24 mm. (No. 64, Harvard series, figs. 29, 30). The constriction of the tympanic pouch has now reached a stage where its connection with the pharynx embraces about twothirds of its former extent. The ventro-mesial margin is accordingly of considerable length. The posterior half of the pouch projects strongly backwards as a wide, cup-shaped fold.

The submeckelian fold forms a wide, almost horizontal shelf (figs. 47-50, s. In. f.). Laterally it reaches considerably beyond the dorsal apex, so that it is clearly visible from above (fig. 30). On lateral View it appears at a considerably higher level than before. This position it has obtained partly as a result of its lateral extension and the consequent flattening of its dorsal surface and partly from the ventral dovmgrowth of that portion of the pouch lying immediately below it (cf. figs. 48-50, with fig. 43).

The manubrial fcssa forms a shallow impression between the submeckelian (s. m. f.) and post-manubrial folds (p. m. f.). The latter is much less prominent in the pig than in the equivalent stage of the cat.

The pig of 25 mm. (Series M3, my collection), while slightly more advanced than the preceding, is essentially similar so far as the tympanic pouch is concerned. figs. 4-7-51 give views of several transverse sections of the structure.

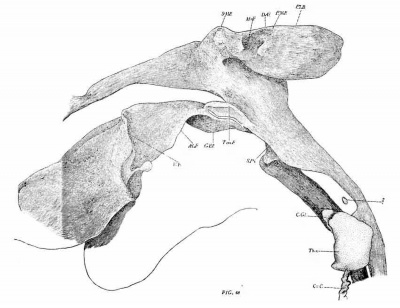

The next step in advance is shown by a eat of 23.1 mm. (No. 466, Harvard collection, figs. 66-67). In this case the tympanic pouch and Eustachian tube are first clearly diiferentiated from each other. The former is a wide, cup—shaped expanse, concave dorsally. As a whole, it has a decided ascending direction. The postero-lateral border (P-L.B.) forms a highly elevated ridge. Immediately back of the dorsal apex it is interrupted by a deep incision—the incissura tensoris (I.Tn.). Anterior to the apex is the submeckelian fold (SM.F.) facing at this stage in the antero—dorsal direction. Laterally its margin is so far upturned as to hide from view the adjacent part of the tubetympanal border.

The msanubrial fossa (i\In.F.) is Very deep. It lies immediately below the tensor incision, bounded anteriorly by the submeckelian fold and posteriorly by the post~manubrial fold (P—M.F.). The external auditory tube lies a short space below the fossa, but is still separated from it by a considerable thickness of connective tissue.

The most noteworthy feature of this stage is the initial division of the pharynx into its oral and nasal portions by the backward extension of the palatine incisions. The oral cavity has been entirely separated from the nasal tube, but the constriction of the pharynx has only begun in its more anterior part. The constriction, as the figures show, takes place in the part lying below the post—salpingeal fold, between it and the tonsillar fold.

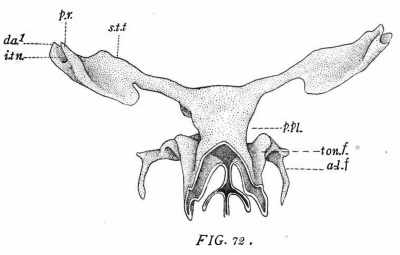

The rabbit of 18 days (Harvard series), while showing a slight difference from the preceding, is yet so closely similar that a full description is unnecessary. Its general features can be seen by consulting fig. '72. The most marked feature is the greater posterior extension of the palatal constriction. The broad grooves continued back from the latter over the sides of the pharynx represent the posterior palatine grooves (Arcus pharyngo-palatinus), p. pl.

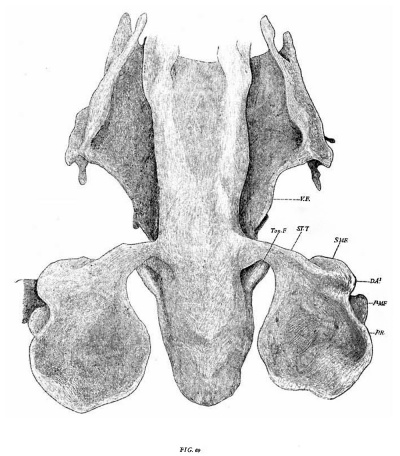

In the pig of 32 mm. (No. 74, Harvard series, figs. 32, 33, 52) the Eustachian tube is more constricted than in the preceding stage. The tympanic pouch projects sharply outwards and backwards. Close to where it joins the tube it gives off the still prominent submeckelian fold. Where the latter and the tubo—tympanal borders meet is the dorsal apex (Recessus anterior, D.A.1). Below the latter on the lateral wall is the now crescent-shaped post—nianubrial fold. The latter arches around underneath the manubrial fossa (Mn.F.) and becomes continuous with the portion extending to the dorso-lateral margin of the pouch. Immediately below the fossa the ventro—lateral surface of the pouch is flattened and is adpressed against the inner part of the external auditory tube. Only an exceedingly thin layer of connective tissue intervenes between the two structures (fig. 52).

The eat of 31 mm. (No. 500, Harvard series, figs. 68-69) gives the final stage in its species. The Eustachian tube is very narrow, while the tympanic pouch is widely expanded, particularly in its posterior part. It still retains its cup—like form, the concave surface fitting closely against the ventro—lateral wall of the auditory capsule. The' submeckelian fold (S—M.F.) is relatively not so prominent as earlier. The dorsal apex or anterior recess (D.A.1) projects strongly outwards. The manubrial fossa (Mn.F.) forms a deep hollow on the more dorsal portion of the lateral surface. It is largely surrounded by the new high and conspicuous post-manubrial fold (P.M.F.). Below the fossa is the surface already mentioned as being in close relation with the external auditory tube. The remaining posterior extension of the pouch is simply applied to the neighboring part of the auditory capsule.

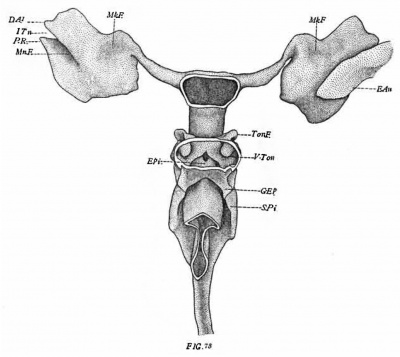

The latest stage studied is shown by a rabbit of twenty-one days. fig. '73 shows the more important points. The manubrial fossa (Mn.F.) is still rather deep in its dorsal half, but vertrally becomes very shallow and there tapers out to a point. The area entering into the constitution of the tympanic membrane is more extensive than in the preceding stage. It now includes a considerable part of the surface in which the manubrial fossa is located.

The Meckelian fossa (Mk.F.) is almost obliterated; it persists as a very shallow impression on the antero-dorsal margin close to the union of the pouch with the Eustachian tube.

Review and Comparisons

The foregoing results render it highly probable that the developmental history of the first pharyngeal pouch is essentially the same in the three species of mammals studied.

This history I have subdivided into three periods, as follows:

- The period of formation of the typical pouch.

- The period of transformation of the pouch into the primary tympanic pouch.

- The period of differentiation of the tympanic pouch and Eustachian tube and their subsequent modifications.

Period I.

The formation of the pharnygeal pouches takes place in the usual manner~—beginning with the most anterior and ending with the most posterior.

When typically developed the first pharyngeal pouch has the form of an approximately transverse vertical fold. At its dorsal lateral angle it projects dorsalwards as a narrow prominence, the dorsal apex (recessus anterior). From this apex three prominent ridges diverge, i. e., antero—lateral, lateral and postero-lateral. - The first extends diagonally inwards and slightly forwards. It forms the sulcus tubetympanicus of Moldenhauer. The lateral. ridge is that by which attachment to the ectoderm is effected. The area of attachment includes nearly its entire extent. Ventrally this ridge is continued into the ventral diverticulum. The postero—lateral ridge extends obliquely inwards and backwards from the dorsal apex to the dorsum of the second pouch.

The ventral diverticula of the first pair of pouches are at first more prominent than those of the succeeding, but they are soon outstripped by the latter. Typically they form a pair of low, but sharp folds, which at first are continuous across the median line of the pharynx.

Period II.

The most important changes leading to the transformation of the first pouch into the primary tympanic pouch are the following: The gradual separation of the pouch from the ectoderm. This process begins on the Ventral side and progresses dorsalwards until complete separation has been effected. In consequence of this separation the lateral ridge becomes greatly reduced and partly absorbed into the neighboring walls of the pouch.

The tubo-tympanal border becomes prolonged in the anterior direction. This change is produced as a result of the elongation in the same direction of the adjacent part of the oral cavity.

The ventral diverticula first become interrupted in the mid-line, and later gradually disappear as a result of absorption into the floor of the pharynx.

The basal or mesial portion of the pouch is displaced ventralwards in consequence of a corresponding displacement in the adjacent part of the pharynx itself. This portion of the pouch thus assumes an almost horizontal position. At first the peripheral part, owing to its continued attachment to the ectoderm, retains its ascending course, joining the mesial portion at a sharp angle. Later, after complete separation from the ectoderm, the peripheral portion also sinks, and thereby assumes a plane more nearly like that of the mesial portion.

The submeckelian fold is formed by the union of the dorsal remnant of the lateral ridge with the diagonal fold separating the basal and peripheral portions of the pouch. At first the fold is continuous anteriorly with the lateral margin (vestibular fold) of the oral cavity. Subsequently this connectionis interrupted and the submeckelian fold then grows out as a prominent shelf—like protuberance underlying Meckel’s cartilage.

Period III.

The transformation of the primary tympanic pouch into the definitive tympanic pouch and Eustachian tube is marked by the following features: The peripheral portion of the pouch becomes relatively fixed in position by the segregation of Meckel’s cartilage with its manubrial process and the auditory capsule.

The basal portion, on the other hand, continues to be carried down by the downgrowth of the alveolo-lingual fold.

The combined effect of these two processes is to give the pouch a peripherally ascending course.

An incision forms at the postero—internal angle of the pouch between it and the dorsum of the second pouch. This incision rapidly extends forwards as an ever—widening cleft between the base of the pouch and the wall of the pharynx.

In consequence of this process the connecting part of the pouch is progressively constricted until it forms a narrow tube, the Eustachian tube.

The remainder of the pouch retains its original wide extent and forms the tympanic pouch.

The later changes relate mainly to modifications in the detailed structure of the tympanic pouch. Among them are the formation of the manubrial fossa, the reduction of the submeckelian fold and the formation of the tympanic membrane.

The manubrial fossa lodges the ventral extremity of the manubrium. At first it is a shallow impression on the lateral surface immediately underlying the posterior part of the submeckelian fold. With the formation of the definitive tympanic pouch it rapidly deepens to form a cup—like depression. Subsequently this elongates at its ventral extremity to form the fissure-like groove characteristic of its final stage.

The submeckelian fold is at first very prominent and partly encloses a Meckelian fossa. The latter later assumes a more flattened form and the fold at the same time broadens until it is absorbed into the wall of the pouch. In the latest stage the submeckelian fold forms only ‘an inconspicuous swelling on the outside of the tubo-tympanal border.

The tympanic membrane is formed by the progressive approximation of the ventro-lateral portion of the tympanic pouch and the neighboring dorso-internal surface of the external auditory tube. At first the two surfaces are separated by a considerable interval filled with connective tissue. This interval later becomes narrower until it is reduced to an exceedingly thin layer—the membrana propria of the definitive membrane. The formation of the tympanic membrane begins on the ventrolateral surface of the pouch, but subsequently it extends dorsalwards so as to include the portion containing the manubrial fossa.

After its differentiation the pouch as a whole increases in width both laterally and longitudinally. Its posterior portion extends backwards as a prominent projection (posterior recess). The margins become upraised and thus the pouch as a whole assumes a cup—like form. The concavity on the dorsal side, corresponding to the promontory, lies close to the latero-Ventral surface of the auditory capsule.

As already mentioned, my results make it highly probable that the developmental history of the first pharyngeal pouch is in all important respects similar in the three types studied. This probability is still further heightened when the results are compared with those obtained by other investigators. Thus Piersol has described and figured the earlier stages in the rabbit. They agree in every important particular with the corresponding stages in the cat and pig.

The most complete comparison can, thanks to the work of Hammar, be made with the human species. Hammar figures nearly every stage from the typical first pharyngeal pouch to the end of foetal life. I have carefully compared Hammar’s descriptions and figures with mine and find that in every important particular they are applicable to the types examined by me. It is in fact diflicult to recognize any important differences, at least as late as the stage when the tympanic pouch and Eustachian tube have been fully differentiated. In the case of the human species the tympanic pouch during the later foetal life gives rise to several outgrowths from its dorso-lateral margin. From one of these the mastoidal cells arise as a complex series of buds. In the rabbit these outgrowths had not formed at as late a stage as that of an animal of 21 days. Whether they are present at the same stage of development in the other two forms I am, at present, unable to say. The latest stages of each, Which I was enabled to examine, showed no trace of them.

Hammar does not lay as much stress as I on the submeckelian fold. He describes its formation correctly, but apparently fails to note its separation from the vestibular folds and its later lateral expansion. His figures, however, leave no doubt that in these particulars the human species agrees with the other types. In some of his figures I am 1101‘. certain whether Hammar means to include the subrneckelian fold as a part of the recessus anterior or to limit the latter to the dorsal apex. His descriptions seem to me to favor the latter alternative. He applies, at any rate, no distinctive term to the fold, and accordingly I have felt free to call it the submeckelian fold.

The foregoing remarks make it apparent that the same essential type of development of the tympanic pouch and Eustachian tube holds in species belonging to four different orders of mammals, *5. e., Rodentia (Lepus), Ungulata (Sus), Carnivora (Felis), and Primates (Homo). So far as known, other species, which have been much less thoroughly investigated, agree with this type. Accordingly, it seems reasonable to suppose that the same type prevails in the majority of ordinary placental mammals and that it represents the typical development of the structures in the class. In forms which are adapted to a special environment (Cetacea, for example) or which are farther removed from the main phylogenetic series (Edentata) it may show important modifications. So far as I am aware, these forms have not yet been investigated in regard to this point. The Marsupials and Monotremes have also not been sufficiently investigated to allow of any assertions being made concerning them. It may be added that a figure by Maurer, showing an early stage of the pharynx in Echidna, bears a striking likeness to that of my 6.5 mm. pig and 6.2 mm. cat.

B. The Modifications and Fate of the Second Pharyngeal Pouch

(b’) The Retrogressive Modifications of the Pouch

We left the second pharyngeal pouch fully and typically developed in a eat of 6.2 mm. (figs. 58-60). Its form at that stage is that of a postero-laterally projecting, vertical fold, which is connected by its entire peripheral margin with the ectoderm of the corresponding groove. At its dorso-lateral angle it is produced into a slight elevation forming a dorsal apex (D.A.2) similar to that of the preceding pouch, but considerably less prominent. On its ventral side the pouch is continued as a prominently projecting ventral diverticulum (V.D.2). The deep portion of the latter is limited to the lateral half of the pharynx, its internal border forming a free edge (fig. 60). At the base of this edge the diverticulum is continued mesially as a low fold similar to the same part in the first pouch. Like the first pouch, the second has four borders and three surfaces. The borders are antero-lateral, posterointernal, lateral and ventral. The surfaces are antero-lateral, medioThe Pharyngeal Pouches in the Mainmalia 211 posterior and dorsal. The antero-lateral border (Ton.F.) extends from the dorsal apex diagonally forwards and inwards to the postero—internal angle of the first pharyngeal pouch. It forms the dividing line between the ‘dorsal and antero—lateral surfaces. The postero—internal border is approximately crescentiform. Laterally, owing to the posterior flexure of the pouch, its course is almost longitudinal, but basally it bends first inwards and then posteriorly and connects with the lateral ridge extending to the third pouch. It separates the dorsal and postero-internal surfaces. The lateral margin forms the part connected with the ectoderm. It separates the antero—lateral and postero—internal surfaces. Ventrally it is continued into the ventral margin, which forms the free edge of the ventral diverticulum.

In a cat of 9.7 mm. (No. 446, Harvard series, fig. 61) the second pouch, beyond a slight increase in size, shows but few new features. For a short distance below the dorsal apex it has separated from the ectoderm—the initial step in the process which in this case begins at the dorsal end and progresses towards the ventral. The separation is accompanied by the ingrowth of mesenchyme into the intervening space.

The latero-ventral angle of the ventral diverticulum is produced into a slight projection. As a result the inner border of the diverticuluin ascends more diagonally to the floor of the pharynx.

In the pig of 10 mm. (No. 401, Harvard series) a departure from the preceding stage is shown by the slightly lower level of the second pouch. In the preceding examples the dorsal line of the pouch lay a short distance above the same line of the pharynx, while in the present stage it lies below it. This condition is probably produced by the changes taking place in the neighboring parts. The hyoid region increases in thickness more rapidly in its dorsal portion than in its relatively passive ventral part. The dorsal portion thus projects outwards over the lower and consequently the second ectodermal groove assumes a more inclined direction than before. With the latero-ventral rotation which the dorsal half of the groove undergoes it naturally results that the attached dorsal portion of the internal pouch accompanies it, at least in part, in the same direction, and thus assumes a more lateral, as well as lower, position.

In the 12 mm. pig (No. 518, Harvard series, figs. 9-12) the second pouch comes to a standstill so far as any lateral growth is concerned. Thus the distance between the lateral margins of the two opposite pouches remains the same as in the preceding stage. The first pharyn» geal pouch, on the contrary, continues to extend rapidly in that direction, and at the same time carries with it the attached adjacent parts. As already mentioned, the antero-lateral margin of the second pouch is continuous anteriorly with the latero-posterior border (S.T.T.) of the first pouch. At first the two join at a considerable angle, but as this border of the first pouch is carried outwards by the growth of the pouch, the attached antero-lateral border of the second pouch (Ton.F.) follows it and thus the angle tends to become drawn out and the borders to form a continuum. Consequently at this stage the antero—lateral border extends diagonally outwards instead of inwards, as in preceding stages.

The lateral fiexure of the antero-lateral margin causes it to arch outwards above the underlying antero-lateral wall. The latter thus forms a well—marked concavity, which is limited internally by the low fold (later part of the alveolo—lingual sinus) connecting the ventral diverticula of the first and second pouches. Owing to its inclined position, this surface will henceforth be called ventro-lateral (fig. 12, c. v.).

Corresponding to the depressed condition of the vcntro-lateral surface, the dorsal surface, which is everywhere closely adpressed against the underlying wall, is raised into a low dome-shaped convexity. The latter I shall call the dorsal prominence (fig. 10, D.Pr.).

The ventral diverticulum (v. d. 2) is reduced to about three-fourths of its former vertical extent. This change I am inclined to attribute, in part at least, to the outward extension of the antero—lateral portion of the pouch. The latter would set up a tension in the remainder of the pouch which would lead to a partial absorption of the diverticulum into the adjacent portion of the pouch. A fact favoring the existence of such a tension is the presence upon the ventro-lateral wall of a narrow fold extending obliquely upwards from the base of the diver-ticulum (fig. 12).

The lateral margin of the second pouch is now largely free from the ectoderm, the connection with the latter persisting only in its more ventral portion, where the corresponding ectodermal groove forms»a deep, vertical pit (fig. 11).

The pig of 14 mm. (No. 65, Harvard series, figs. 14-17) shows the second pouch slightly reduced in vertical extent, but produced at its ventro-lateral angle into a long, fine process (Fl.P.), the distal end of which is attached to the ectoderm. Elsewhere the pouch is free and is removed by a wide interval from the ectoderm. This condition is the result of the rapid growth in thickness of the hyoid region. As the figures (12 of last stage and 17 of this) show, this growth has not been accompanied by a corresponding increase in the pouch, which at this stage remains of the same width as in the preceding stage. Consequently, as the second pharyngeal groove is displaced more and more lateralwards, the attached ventro—lateral angle becomes drawn out into the process here shown. Owing to its form, I designate the latter the filiform process (fl. p.).

The lateral margin of the pouch is considerably less prominent than hitherto. This change appears to be produced by an actual regression of the margin. This is indicated by the fact that the distance between the lateral margins of the two opposite pouches is slightly less than in the preceding stage. The regression is probably attributable to the tension exerted upon this margin by the continued lateral extension of the adjoining antero-lateral margin with which it now joins at a. wide angle.

As just mentioned, the antero—lateral margin (ton. f.) has continued to extend in the lateral direction. It thus has a decided antero—latera1 course. For this reason it is inappropriate to call it by the term hitherto used, and accordingly I shall hereafter speak of it as the dorsolateral margin.

The dorsal apex (D.A.2) of the pouch now forms only a slight protuberance at the posterior extremity of this margin (fig. 15).

In consequence of the extension laterally of the dorso-lateral margin the underlying ventro—lateral surface has acquired the form of a deep concavity (fig. 17, c. v.). The overlying dorsal wall is correspondingly raised as a broad dome—shaped prominence (fig. 15, D.Pr.). I The ventral diverticulum (v. d. 2)- has almost ceased to exist as a distinct feature. Only in its more peripheral part does it project to a fair degree below the ventro-lateral line of the pharynx. Its middle part has largely disappeared owing" to the downgrowth of the alveololingual ridge (fig. 17, al. f.) and the union of the latter with the sinus piriformis (fig. 17, s. pi.). The place of the original diverticulum is indicated by a widening of the continuous ventro-lateral fold thus formed.

The more internal part of the diverticulum persists as a slight ridge on the inner side of the ventro-lateral fold (fig. 17).

In the 17 mm. pig (figs. 19-22) the second pouch has entirely severed its connection with the ectoderm, leaving the filiform process terminating blindly in the mesenchyme. Owing to the continued lateral extension of the dorso—lateral margin (Ton.F.), the original lateral border now forms a continuum with it. This leaves the dorsal apex as a minute protuberance at its posterior extremity.

The dorso-lateral margin shows no increase in length, but anteriorly it has been carried farther outwards in consequence of the extension of the tympanic pouch in that direction. It thus acquires a course almost in line with the postero—lateral margin (s. t. p.) of the latter. Only a slight notch remains to indicate the dividing line between them.

The ventral diverticulum (v. d. 2) has now nearly disappeared, having been absorbed by the downgrowth of the ventro-lateral margins of the pharynx.

The features of the second pouch in the pig of 17 mm. are essentially duplicated in cats of 10.7 mm. and 12 mm.

A rabbit of 14 days (No. 157, Harvard series, fig. '70) shows a stage somewhat intermediate between that just described and the next.

The same remark is also applicable to an 18 mm. pig (Series M3, of my collection).

In a pig of 20 mm. (No. 542, Harvard series, figs. 23-27) the second pharyngeal pouch is chiefly modified as regards length and direction. As indicated by the figures, these modifications are related to the ventral (caudal) flexure of the posterior half of the pharynx. As already mentioned (see account of tympanic pouch), the tympanic pouch has at this time become relatively fixed in position by the formation about it of the related cartilages. Consequently, as the pharynx continues to bend toward the ventral side, the attached second pouch tends to be drawn out and flattened (fig. 23). This process is also accelerated by the continued deepening of the ventro-lateral margin of the pharynx.

The hitherto prominent dorsal prominence is now reduced to a low swelling located at the postero-internal angle of the tympanic pouch. No lateral extension of this part of the pouch has taken place since the 17 mm. stage. Its middle and posterior portions, on the contrary, have shrunken slightly, due probably to the tension produced by its elongation in the ventral direction and the continued downgrowth of the adjacent ventro-lateral margin (A-L.F.) of the pharynx.

Posteriorly the second pouch thus forms a low ridge situated on the outer side of the ventro-lateral fold (= conjoined alveolo-lingual and piriform sinuses).

The shrunken filiform process is still recognizable. The Pharyngeal Pouches in the Mamrnalia 215 The dorsal apex has been absorbed into the neighboring surface of the dorsal prominence.

The ventral diverticulum forms only an inconspicuous fold in the same situation as hitherto.

(b") The Formation of the Tonsillar Fold

The eat of 15 mm. (No. 436, Harvard series, figs. 63-64) gives us the initial step in the transformation of the remnant of the second pouch into the tonsillar fold.

In this stage the dorso—lateral fold, representing the second pouch, no longer forms a continuum with the adjacent border of the tympanic pouch, but is separated from the latter by an indentation which extends quite across its dorsal side to the longitudinal ridge (P.S.F.), forming its mesial boundary. .

The second pouch thus forms an arched lateral fold. The lateral margin (Ton.F.) of the fold lies on a level with the ventro—lateral line of the pharynx. The ventral side is concave; the dorsal correspondingly convex. Anteriorly the fold is continued immediately under the ventr0internal angle of the tympanic pouch and extends to the base of the vestibular fold. Internally the fold is limited on the ventral side by the alveolo—lingual fold, on the dorsal by the adjacent surface of the pharynx. The structure thus defined is the tonsillar fold (tonsillar sinus). The concavity on its ventral side corresponds to the tonsillar prominence (tonsillenhocker).

There is no trace at this stage of the filiform process.

The rabbit of 161/2 days (No. 5'76, Harvard series, fig. '71) shows an essentially similar condition. The fold (ton. f.) is more strongly arched and its lateral edge lies some distance above the lower edge of the alveolo—lingual groove. The fold is widest immediately under the post-salpingeal ridge (p. s. f.). Its anterior continuation forms a low ridge, which probably represents an extension of the fold over the adjacent surface of the pharynx.

In the 24 mm. pig (No. 64, Harvard series, figs. 29-30) the tonsillar fold is removed by a considerable interval from the base of the tympanic pouch (fig. 30"). Between them the surface of the pharynx is depressed, forming the palatal constriction. The present position of the fold is due to the formation of this constriction and to the continued downgrowth of the alveolo—lingual margin (A-L.F.) with which it is closely associated. In form the tonsillar fold (Ton.F.) of the pig of this stage bears a greater resemblance to that of the cat than to the same structure in the rabbit. The tonsillar fold of the latter has a more decided ascending plane than the others.

In the eat of 23.1 mm. (No. 466, Harvard series, figs. 66-67) the tonsillar fold (Ton.F.) has attained its definite position. The palatal constriction has now separated the nasal cavity from the mouth and has begun to encroach upon the pharynx. The tonsillar fold forms a wide, diagonally ascending arched fold on the side of the oral portion. Its ventro—lateral surface is, as usual, deeply concave.

The pig of 32 mm. (No. 74, Harvard series, fig. 32) shows the tonsillar fold (Ton.F.) more nearly erect than in the cat. In outline it is approximately quadrangular and its outer (: ventral) surface is less concave than in the cat. Ventrally it is limited by the alveolo— lingual ridge (A-L.F.), which at this stage no longer forms the lower line of the pharynx, but lies on the outer side of the glosso-epiglottic fold (vallecula glosso-epiglottica).

In the 31 mm. cat (No. 500, Harvard series, figs. 68-69) the tonsillar fold (Ton.F.) has essentially the same form as in the 23 mm. cat. As in the pig last described, its lower boundary——the alveolo—lingual ridge——now lies on the outer side of the glosso—epiglottic fold The palatal constriction has now completed the division of the pharynx into nasal and oral portions.

The narrow cord shown in the figure parallel with the tonsillar fold is an epithelial structure which lies free in the connective tissue to the outer side of the fold. Its significance I have not been able to solve.

In none of the stages so far studied did I observe any clear indications of the formation of lymphoidal tissue in connection with the tonsillar fold.

In the rabbit of 21 days (fig. '73) the tonsillar fold (Ton.F.) is approximately vertical. Its lateral surface is deeply concave and lies between a dorsal and a ventral fold. The former corresponds to the supra-tonsillar recess and evidently represents the derivative of the second pouch. The ventral fold I am inclined to homologize with the infra-tonsillar recess (V.T.) which is a derivative of the pharynx. I-Iammar, however, who describes a similar stage in the rabbit as well as in man and several other mammals, fails to mention this fold as the part in question. I regret that with the relatively few later stages at my disposal I have not been able to solve this problem satisfactorily.

Review and Comparisons

My investigations make it probable that the history of the second pouch, so far, at least, as its earlier stages are concerned, is similar in the forms studied. Unfortunately, my rabbit and cat material was not sufficiently abundant to enable me to make this statement without qualification. However, the specimens I did examine agreed very closely with corresponding stages in the pig series. The later stages were not sufficiently numerous to enable me to make comparisons. In its general features the development of the tonsillar fold seems to agree in all forms; in details, there are undoubtedly considerable differences in tlie different species.

The history of the pouch, as mainly determined in the pig, divides itself in two periods—-the first characterized by a series of retrogressive changes in the pouch, the second by a series of progressive changes converting the remains of the pouch into the tonsillar fold.

When typically developed the second pouch has the form of a poster0laterally projecting vertical fold. Dorsally the dorso-lateral angle is produced as a dorsal apex. Ventrally it shows a prominent ventral diverticulum. Connection with the ectoderm is more extensive than in any other pouch, the entire lateral margin taking part in the formation of the verschlussmembmn.

The earlier modifications of the pouch are connected with the rapid lateral growth of the hyoid region. The pouch, on the other hand, remains stationary. Parts of it are, however, connected with adjoining structures, and, as these undergo displacement connected with subsequent growth, the pouch becomes profoundly modified.

Separation of the pouch from the ectoderm begins on the dorsal side and extends progressively toward the ventral. The last point to remain attached is the ventro-lateral angle of the ventral diverticulum, which becomes drawn out into a thin cord, the filiform process. The latter subsequently separates and then shrinks in length and disappears.

Largely as a result of the lateral extension of the adjoining tympanic pouch the dorso-anterior portion of the second pouch is drawn farther outwards. Its margin, which originally extended forwards and inwards, acquires an antero-lateral course and thus comes to form a continuum with the posterior border of the tympanic pouch. The underlying antero-lateral surface becomes ventro-lateral and its wall becomes depressed to form a deep concavity, which corresponds to the later tonsillar projection. The closely adpressed dorsal Wall is correspondingly raised into a dome—shaped swelling, the dorsal prominence.

After its separation from the ectoderm the original lateral margin of the pouch recedes towards the median line. At first it forms a slight projection at the postero-internal angle of the pouch, but later this is absorbed and then forms a continuum with the dorso—lateral fold.

The ventral diverticulum early diminishes in size and later is absorbed by the downgrowth of the alveolo—lingual fold.