Abnormal Development - Listeria

| Embryology - 28 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| Educational Use Only - Embryology is an educational resource for learning concepts in embryological development, no clinical information is provided and content should not be used for any other purpose. |

Introduction

The bacterium Listeria monocytogenes is the pathogenic form of the 7 listeria species. Infection is generally through ingestion of organisms in contaminated food. Maternal symptoms may be mild, fetal effects can range from insignificant through to major abnormalities. Maternal treatment relates to potential developmental effects. Pregnancy greatly increases the risk of listeriosis, with pregnant women about 60% of all cases (male and female) aged 10 to 40 years. Similar effects are seem in other mammalian species.[1] See also the listeriosis review article[2] and the Guinea pig placenta listeria model[3] Generalized suppression of immunity during pregnancy is suggest to have a role in susceptibility, though recent results in a mouse model suggest that susceptibility can occur very early in a pregnancy and may relate to enteric carriage rate.[1]

| Bacterial Links: bacterial infection | syphilis | gonorrhea | tuberculosis | listeria | salmonella | TORCH | Environmental | Category:Bacteria |

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Listeria Pregnancy |

Listeria Infection

- ingestion of contaminated food

- colonization of the intestine

- intestinal translocation

- replication in the liver and spleen

- either the resolution of infection or spread to other organs resulting in a systemic infection

Lineage

Placental Infection

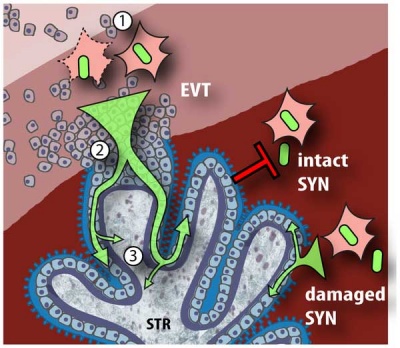

Model of L. monocytogenes mechanisms for breaching the maternal-fetal barrier[6] (text below modified from original reference)

Gram Stain

Bacterial staining procedure named after Hans Christian Gram (1853 - 1938). Generally divides bacteria into either:

- Gram-positive bacteria purple crystal violet stain is trapped by layer of peptidoglycan (forms outer layer of the cell).

- Gram-negative bacteria outer membrane prevents stain from reaching peptidoglycan layer in the periplasm, outer membrane then permeabilized and pink safranin counterstain is trapped by peptidoglycan layer.

- Links: Histology Stains

Australian NHMRC Guidelines

NHMRC Guidelines "are intended to promote health, prevent harm, encourage best practice and reduce waste" have replaced the earlier historic 1988 NHMRC recommendations.

- Links: Clinical Practice Guidelines - Pregnancy Care (2019) | PDF | Related Documents | Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines | NHMRC guidelines

| Historic - NHMRC (1988) Recommendations | ||

|---|---|---|

Neonates be assessed for follow-up care under the following conditions:

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Suyemoto MM, Spears PA, Hamrick TS, Barnes JA, Havell EA & Orndorff PE. (2010). Factors associated with the acquisition and severity of gestational listeriosis. PLoS ONE , 5, e13000. PMID: 20885996 DOI.

- ↑ Doganay M. (2003). Listeriosis: clinical presentation. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. , 35, 173-5. PMID: 12648833

- ↑ Bakardjiev AI, Stacy BA & Portnoy DA. (2005). Growth of Listeria monocytogenes in the guinea pig placenta and role of cell-to-cell spread in fetal infection. J. Infect. Dis. , 191, 1889-97. PMID: 15871123 DOI.

- ↑ Chan LM, Lin HH & Hsiao SM. (2018). Successful treatment of maternal listeria monocytogenes bacteremia in the first trimester of pregnancy: A case report and literature review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol , 57, 462-463. PMID: 29880186 DOI.

- ↑ Simon K, Simon V, Rosenzweig R, Barroso R & Gillmor-Kahn M. (2018). Listeria, Then and Now: A Call to Reevaluate Patient Teaching Based on Analysis of US Federal Databases, 1998-2016. J Midwifery Womens Health , 63, 301-308. PMID: 29799155 DOI.

- ↑ <pubmed>20107601</pubmed>| PLoS

Reviews

Lamont RF, Sobel J, Mazaki-Tovi S, Kusanovic JP, Vaisbuch E, Kim SK, Uldbjerg N & Romero R. (2011). Listeriosis in human pregnancy: a systematic review. J Perinat Med , 39, 227-36. PMID: 21517700 DOI.

Posfay-Barbe KM & Wald ER. (2009). Listeriosis. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med , 14, 228-33. PMID: 19231307 DOI.

Goldenberg RL & Thompson C. (2003). The infectious origins of stillbirth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 189, 861-73. PMID: 14526331

Albritton WL, Cochi SL & Feeley JC. (1984). Overview of neonatal listeriosis. Clin Invest Med , 7, 311-4. PMID: 6398177

Articles

Jackson KA, Iwamoto M & Swerdlow D. (2010). Pregnancy-associated listeriosis. Epidemiol. Infect. , 138, 1503-9. PMID: 20158931 DOI.

Bakardjiev AI, Stacy BA, Fisher SJ & Portnoy DA. (2004). Listeriosis in the pregnant guinea pig: a model of vertical transmission. Infect. Immun. , 72, 489-97. PMID: 14688130

Topalovski M, Yang SS & Boonpasat Y. (1993). Listeriosis of the placenta: clinicopathologic study of seven cases. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 169, 616-20. PMID: 8372871

Storrs CN & Partridge JW. (1980). Listeria infections in the newborn. Arch. Dis. Child. , 55, 246. PMID: 7387172

Luft BJ & Remington JS. (1982). Effect of pregnancy on resistance to Listeria monocytogenes and Toxoplasma gondii infections in mice. Infect. Immun. , 38, 1164-71. PMID: 6818146

Scott JM & Henderson A. (1968). A case of listeriosis of the newborn. J. Med. Microbiol. , 1, 97-104. PMID: 4990031 DOI.

Textbooks

Medical Microbiology - Listeria | Listeria Search

Search Pubmed

Search PubMed: Congenital Listeria | Abnormal Embryology Listeria | Abnormal Development Listeria

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- NHMRC (Australia) - Prevention of Listeria (PDF)

- Medline Plus

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (UK) Infection and Pregnancy - study group recommendations (Jun 2001)

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 28) Embryology Abnormal Development - Listeria. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Listeria

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G