Puberty Development

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Introduction

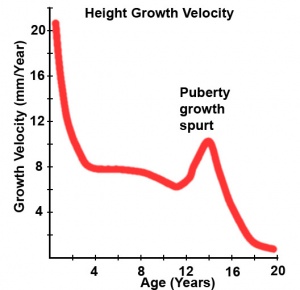

These notes cover normal postnatal development during the puberty period which occurs mainly in the early teenage years. Triggers to puberty include neuroendocrine changes in hypothalamic expression of kisspeptin which is suggested in turn to change gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) levels. (More? Kisspptin | Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone | Endocrine Notes - Hypothalamus)

Male and female sexual differentiation giving the complete sexual phenotype involves two main phases.

- Primary, is the formation of an ovary or a testis from the bipotential gonad in the embryo.

- Secondary, is the development of the female and male phenotypes in response to hormones secreted by the ovaries and testes which occurs in the teen years during adolescence. This is initiated by the renewed expression of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) which is minimal in childhood.

Of general interest would be the timing differences between girls and boys when puberty commences (girls before boys). Early onset of puberty (precocious) occurs more frequently in girls than boys, in contrast late onset (delayed) occurs more frquently in boys than girls.

There are a number of clinical puberty indicators; for males testicular volume increase (>4cc) corresponding to onset of spermatogenesis, for females menstruation and secondary sex characteristics of breast development (measured by the Tanner stages).

- Links: Postnatal | Neonatal Development | Puberty Development | Genital

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Puberty | Tanner stages | kisspeptin | Precocious Puberty | Delayed Puberty | |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

Puberty

Can occur over a broad range of time and differently for each sex: girls (age 7 to 13) boys (age 9 to 15).

The physical characteristics that can be generally measured are: genital stage, pubic hair, axillary hair, menarche, breast, voice change and facial hair.

The physiological process is initiated by the hypothalmus releasing gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) which signals the pituitary to release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) which in turn signals throughout the body sexual development.

Tanner Stages

(tanner scale) An anatomical staging system for measuring male/female sexual development at puberty. Stages were based upon genital and secondary sex characteristic development and named after James M. Tanner who, along with W.A. Marshall, published the stages for both girls (1969[4]) and boys (1970[5]. It is not a system for determining age.

| Tanner Stage | Genitals (male) | Breasts (female) | Pubic hair (male and female) |

|---|---|---|---|

| prepubertal (testis volume < 1.5 ml small penis (3 cm or less) (age 9 and younger) |

no glandular tissue areola follows the skin contours of the chest (prepubertal) (age 10 and younger) |

no pubic hair at all (prepubertal state) (age 10 and younger) | |

| testis volume 1.6 to 6 ml skin on scrotum thins, reddens and enlarges penis length unchanged (age 9–11) |

breast bud forms with small area of surrounding glandular tissue areola begins to widen (age 10–11.5) |

small amount of long, downy hair with slight pigmentation at the base of the penis and scrotum (males) or on the labia majora (females) (age 10–11.5) | |

| testis volume 6 to 12 ml scrotum enlarges further penis begins to lengthen to about 6 cm (age 11–12.5) |

breast begins to become more elevated and extends beyond the borders of the areola, which continues to widen but remains in contour with surrounding breast (age 11.5–13) |

hair becomes more coarse and curly begins to extend laterally (age 11.5–13) | |

| testis volume 12 to 20 ml scrotum enlarges further and darkens penis increases in length to 10 cm and circumference (age 12.5–14) |

increased breast size and elevation areola and papilla form a secondary mound projecting from the contour of the surrounding breast (age 13–15) |

adult–like hair quality extending across pubis but sparing medial thighs (age 13–15) | |

| testis volume > 20 ml adult scrotum and penis of 15 cm in length (age 14+) |

breast reaches final adult size areola returns to contour of the surrounding breast with a projecting central papilla (age 15+) |

hair extends to medial surface of the thighs (age 15+) | |

| Note that while typical ages are shown in brackets within the table, this is not a system for determining age.

Based upon W.A. Marshall and J.M. Tanner, published stages for girls (1969[4]) and boys (1970[5]). Links: Tanner stages | puberty | genital | Female | Male | |||

| Tanner Stages (Expand to open) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Links: Endocrinology - Puberty | Endocrinology - Endocrine changes in puberty | Endocrinology - Gonad | Clinical Methods - The Adolescent Patient | Clinical Methods - Staging Criteria for Secondary Sexual Development | NICHD - Puberty | UCSF - Male Development |

Precocious Puberty

Premature development of the signs of puberty which can occur in both girls (before age 7 or 8) and in boys (before age 9).

- Links: Endocrinology - Precocious sexual development | NICHD - Precocious Puberty | Nemours Foundation - Precocious Puberty | MedlinePlus - Obesity May Trigger Earlier Puberty for Girls | Time Magazine - Teens Before Their Time |

Delayed Puberty

Determined in boys by a lack of increase in testicular volume by the age of 14 years. In girls, no breast development by the age of 13.5 years and a lack of menstruation by the age of 16 years. There can also be a "pubertal arrest" where there is no progress in puberty over 2 year period.

- Links: Endocrinology - Delayed puberty | Endocrinology - Definitions and causes of delayed puberty | Nemours Foundation - Delayed Puberty

Kisspeptin

While the hypothalamic expression of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) is a known puberty trigger, it was not known what initiated the GnRH secretion. Recent research suggests that an earlier signal could come from increased neuronal and hypothalamic expression of a peptide family (kisspeptins) and their receptor (G protein-coupled receptor GPR54) in the hypothalamus. A single gene (Kiss1) encodes these 145 amino acid kisspeptins and it was originally identified as a human metastasis suppressor gene (suppresses melanomas and breast carcinomas without affecting tumorigenicity).[6]

Two hypothalamic nuclei, the arcuate nucleus and anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV), are thought to contain the kisspeptin secreting neurons.

The anteroventral periventricular nucleus differs in males and females (sexually dimorphic). The arcuate nucleus (and medial preoptic area, MPOA) is linked into the olfactory system, through the vomeronasal organ, perhaps in relation to the influence of pheromones on sexual behavior and neuroendocrine function (in mice).[7]

Why Kisspeptin?

The original discovery of the peptide was made by scientists located in Hershey, PA, USA and named the gene "Kiss1" after the "Hershey chocolate kiss".

Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH)

Neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (and other nuclei) synthesise this hormone along with gonadotrophin associated peptide (GAP), which are both released and transported by hypophyseal portal capillaries to the anterior pituitary and bound by a membrane receptor.

GnRH increases during early puberty, followed by an increased pituitary responsiveness, then increasing sex steroid levels and then increased nocternal Luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion.

- Links: Endocrinology - GnRH and the control of gonadotrophin synthesis and secretion | Endocrinology - Synthesis of GnRH and its actions on pituitary gonadotrophs |

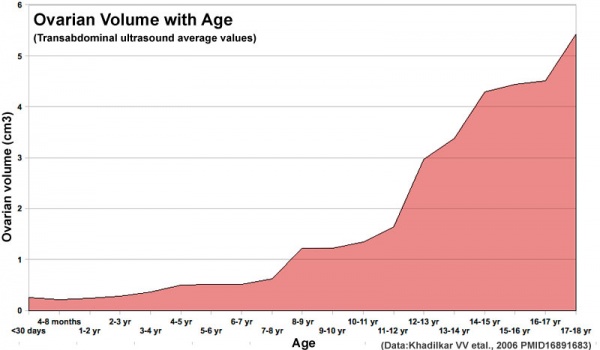

Female Postnatal Ovary Growth

In females at puberty, surges in lutenizing hormone (LH) stimulate the resumption of meiosis in oocytes arrested in the first meiosis (prophase 1 diplotene stage) from fetal life through postnatal childhood. This and other changes results in overall ovarian growth.

Human ovary postnatal volume growth[8]

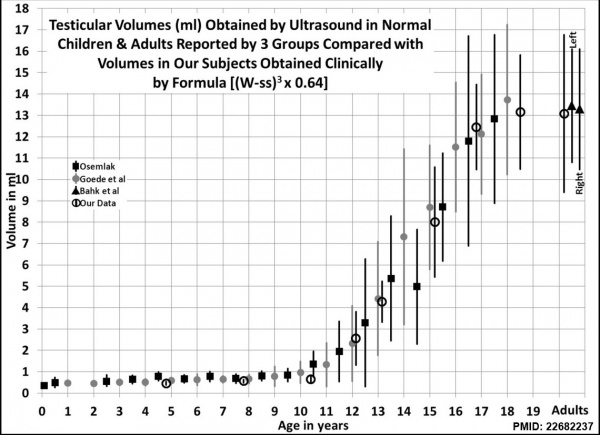

Male Postnatal Testis Growth

Male puberty testicular volume graph[9]

Testicular volume increase at puberty can be measured by: including orchidometry, rulers, calipers, and ultrasonography. There is also an earlier empirical formula developed by Lambert[10] used to estimate testicular volume.

Ellipsoid Equation

A recent publication has developed a technique using a centimeter ruler[9] with results similar to ultrasound. Equivalent to the ellipsoid equations, to calculate testicular volumes with corrections of the width (W), length (L), and height (H) of the testis obtained in the scrotum to avoid the inclusion of the scrotal skin and epididymis.

- Ellipsoid equation W2 x L x π/6

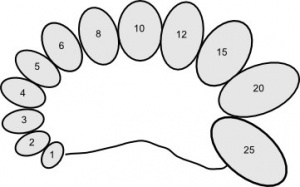

Orchidometer

Male puberty testicular volume graph[9]

Testicular volume increase at puberty can be measured by: including orchidometry, rulers, calipers, and ultrasonography. There is also an earlier empirical formula developed by Lambert[10] used to estimate testicular volume.

Animal Puberty

| Phase | Rat | Dog (beagle) | Primate (monkey) |

| Neonatal | Birth to postnatal Day 7 | Birth–3 weeks | Birth to 3–4 months |

| Infantile | Postnatal Days 8–21 | 3–5 weeks | Up to 29 months |

| Juvenile/prepubertal | Postnatal Days 22–37 | 5 weeks–6 months | Up to 43 months |

| Pubertal | Postnatal Days 37–38 | 6–8 months | 27–30 months |

References

- ↑ Lee HK, Choi SH, Fan D, Jang KM, Kim MS & Hwang CJ. (2018). Evaluation of characteristics of the craniofacial complex and dental maturity in girls with central precocious puberty. Angle Orthod , 88, 582-589. PMID: 29708396 DOI.

- ↑ Day FR, Elks CE, Murray A, Ong KK & Perry JR. (2015). Puberty timing associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and also diverse health outcomes in men and women: the UK Biobank study. Sci Rep , 5, 11208. PMID: 26084728 DOI.

- ↑ Blakemore SJ, Burnett S & Dahl RE. (2010). The role of puberty in the developing adolescent brain. Hum Brain Mapp , 31, 926-33. PMID: 20496383 DOI.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Marshall WA & Tanner JM. (1969). Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch. Dis. Child. , 44, 291-303. PMID: 5785179

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Marshall WA & Tanner JM. (1970). Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch. Dis. Child. , 45, 13-23. PMID: 5440182

- ↑ Seminara SB. (2006). Mechanisms of Disease: the first kiss-a crucial role for kisspeptin-1 and its receptor, G-protein-coupled receptor 54, in puberty and reproduction. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab , 2, 328-34. PMID: 16932310 DOI.

- ↑ Dungan HM, Clifton DK & Steiner RA. (2006). Minireview: kisspeptin neurons as central processors in the regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology , 147, 1154-8. PMID: 16373418 DOI.

- ↑ Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Kinare AS, Tapasvi HS, Deshpande SS & Maskati GB. (2006). Ovarian and uterine ultrasonography in healthy girls between birth to 18 years. Indian Pediatr , 43, 625-30. PMID: 16891683

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Sotos JF & Tokar NJ. (2012). Testicular volumes revisited: A proposal for a simple clinical method that can closely match the volumes obtained by ultrasound and its clinical application. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol , 2012, 17. PMID: 22682237 DOI.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 LAMBERT B. (1951). The frequency of mumps and of mumps orchitis and the consequences for sexuality and fertility. Acta Genet Stat Med , 2, 1-166. PMID: 15444009

- ↑ Beckman DA & Feuston M. (2003). Landmarks in the development of the female reproductive system. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. , 68, 137-43. PMID: 12866705 DOI.

Reading

Most embryology textbooks (by definition) do not cover postnatal developmenty in any detail. The links below are to useful scientific external online resources.

- PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT, GROWTH, MATURATION, AND AGEING

- Patterns of Human Growth (PDF document)

- Causes and Mechanisms of Linear Growth Retardation

The links below are to general public external text resources (this listing is for information purposes only and is not intended as an endorsement of a commercial product).

- Ready, Set, Grow!: A What's Happening to My Body? Book for Younger Girls, by Lynda Madaras and Linda Davick

- What's Happening to My Body? Book for Boys: The New Growing-Up Guide for Parents and Sons, Third Edition by Lynda Madaras, Area Madaras, Dane Saavedra, and Simon Sullivan

- Sex, Puberty, and All That Stuff: A Guide to Growing Up, by Jacqui Bailey and Jan McCafferty

Reviews

Muir A. (2006). Precocious puberty. Pediatr Rev , 27, 373-81. PMID: 17012487

Palmert MR & Boepple PA. (2001). Variation in the timing of puberty: clinical spectrum and genetic investigation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. , 86, 2364-8. PMID: 11397824 DOI.

Dungan HM, Clifton DK & Steiner RA. (2006). Minireview: kisspeptin neurons as central processors in the regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology , 147, 1154-8. PMID: 16373418 DOI.

Articles

Banerjee I, Trueman JA, Hall CM, Price DA, Patel L, Whatmore AJ, Hirschhorn JN, Read AP, Palmert MR & Clayton PE. (2006). Phenotypic variation in constitutional delay of growth and puberty: relationship to specific leptin and leptin receptor gene polymorphisms. Eur. J. Endocrinol. , 155, 121-6. PMID: 16793957 DOI.

Search Pubmed

April 2010

- puberty development - All (9053) Review (1407) Free Full Text (1747)

- puberty - All (26880) Review (3582) Free Full Text (4312)

- early puberty - All (4190) Review (676) Free Full Text (821)

Search Pubmed Now: puberty development | puberty | early puberty |

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

Australian

American

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Puberty | Precocious Puberty

- American Academy of Family Physicians Puberty: What to Expect When Your Child Goes through Puberty

- Nemours Foundation Precocious Puberty | Delayed Puberty |

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Puberty Development. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Puberty_Development

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G