Paper - The developmental history of the primates

| Embryology - 19 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Hill JP. The developmental history of the primates. (1932) Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London B, 221:45-178. PubMed 20775204

| Online Editor |

|---|

| This historic 1932 paper by James Hill describes several early human embryos.

|

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

The Developmental History of the Primates

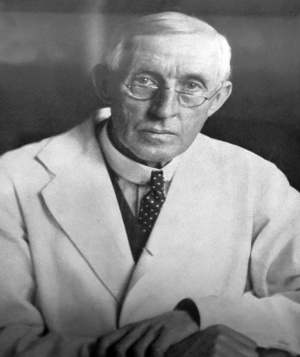

Professor. J. P. Hill’s Croonian Lecture.

The following is an abstract of the Croonian Lecture for 1929, on the developmental history of the primates, delivered before the Royal Society by Professor J. P. Hill, F.R.S.

Starting with the relatively simple developmental conditions met with in the Lemuroidea, Professor Hill considered the question of how the much more specialized and modified developmental relations found in the higher primates might be supposed to have arisen as the result of adaptive specialization, involving more especially acceleration and abbreviation in the developmental processes. A broad survey of the early development and placentation in representatives of the chief divisions of the order had led to the recognition of four main stages in its evolutionary history — lemuroid, tarsioid, pithecoid, and anthropoid.

The existing lemurs, said Professor Hill, were regarded, from the developmental point of view, as remnants of that basal lemurine stock from which the higher primates took their origin. In their development they exhibited a combination of primitive features with others which wereycertainly advanced, and which foreshadowed conditions characteristic of the higher types. Primitive features were evinced in the constitution of the blastocyst and its central type of development, in the disappearance of the covering trophoblast and consequent exposure of the embryonal ectoderm, in the origin and mode of spreading of the mesoderm, in the formation of amnion by folds, and in the development of the allantois as a free vesicle. Among the advanced features might be included the relatively early establishment of a complete chorion and its direct and complete vascularization by the ingrowth into it of the allantoic vessels and the reduction of the Template:Yolk-sac and its vessels. Their placentation was regarded as genuinely primitive, and the lecturer considered the manner in which the more specialized haemochorial type of the higher primates might have been substituted for it.

In the tarsioid stage, as exemplified by the existing tarsius, was to be observed the retention of certain lowiy features characteristic of the lemuroids — for example, the exposure of the embryonal ectoderm and the (levelcpmcnt cf the amnion by fold formation. At this stage certain developmental tendencies could be discerned which were already foreshadowed in the lemuroids — namely, the still more precocious differentiation of the extra-embryonal mesoderm, coelom, and chorion, and the replacement of the vesicular allantois by the almost solid Template:Connecting stalk, all of them features in which tarsius anticipates the pithecoids. Also present were certain definite advances on the lemuroid, in particular the acquisition by an early blastocyst of a direct attachment to the uterine lining and the resulting formation of a massive discoidal placenta of the deciduate haemochorial type.

In discussing the development of the placenta Professor Hill showed that the trophoblast was unique, both in its histological characters and in its behaviour, and on these grounds concluded that the tarsius placenta was too specialized to have been the actual forerunner of that of the pithecoids, but would seem to have developed along lines of its own, as a parallel formation. Acceptancejof this conclusion in regard to the placenta in no way lessened the significance of the tarsioid phase as the more important transitional stage in the evolution of the developmental processes of the primates. It was only to suppose that the pithecoids took origin from another branch of the tarsioid stock in which the attempt at the formation of a haemochorial placenta. proceeded along lines comparable with those which were found in the existing pithecoids.

Passing to a consideration of the pithecoid stage, the lecturer said that the justification for the recognition of this stage rested on the occurrence in the platyrrhine and ca‘.-arrhine monkeys of certain striking resemblances in their early development, all of the nature of definite developmental advances on the tarsioid condition. ~ In this stage the amnion no longer developed by fold formation, since its cavity, the primitive amniotic cavity, arose as a closed-space in the ectodermal cell mass of the very early blastocyst. The primaryattachment of the blastocyst to the uterine wall was always effected by the trophoblast over the embryonal pole. A second attachment was also usually formed at the anti-embryonal pole, in which case the placenta was bidiscoidal. The extra-embryonal mesoderm and coelom and the mesodermal primordium of the connecting stalk were formed even more precociously than in the tarsioid. The extra-embryonal mesoderm (the so-called primary mesoderm of the early human blastocyst), though homologous with that of the tarsioid, was no longer of direct primitive streak origin, but appeared to arise, as in hapale, as a proliferation from the hinder margin of the shield ectoderm and the adjoining amniotic ectoderm. The trophoblast always became clearly distinguishable into cellular and syncytial layers. The syncytiotrophoblast exhibited erosive and destructive properties, and had the capacity of proliferating and of penetrating more or less -deeply into the maternal decidual tissue in the form of an irregular network. The existence of certain well-marked differences in the behaviour of the trophoblast and in the structure of the placenta in the two groups of monkeys, and the very striking similarities in the development of the placenta in the catarrhines and the anthropoids, suggs.-sted that the platyrrhines separated very early from the parent stem to pursue a path of their own, while the catarrl1ine.s furnished the stock from which the anthropoids originated.

In the anthropoid stage were grouped together anthropoid apes and man, and in this stage was to be seen the culmination of developmental adaptation so far as the primates were concerned. Though there was no knowledge about the earlicr stage in the development of the anthropoid apes, enough was known - thanks to the labours of Selenka and Strahl - of their later stages and placentation to justify the belief that their development conformed in all essentials to the human type, so that for the details of early anthropoid ontogeny the work of the human embryologist must be relied on.

The outstanding feature of the early human blastocyst was its extraordinary precocity., as exemplified, for example, in the relations it very early acquired to the uterine lining, and in the remarkably early differentiation of its trophoblast and its extra-embryonal mesoderm It was no longer content to undergo its development in the uterine lumen, as did the blastecysts of the lower primates, but, while still quite minute, it burrowed its way through the uterine epithelium and implanted itself in the very vascular sub-epithelial desidual tissue of the uterus“; Therein it formed for itself a decidual cavity and underwent its subsequent development, completely embedded in the maternal tissue. In this way the primate germ reached the acme of its endeavour to maintain itself in the uterus and to obtain an adequate supply of nutriment at the earliest possible moment. It was a significant fact that just the pithecoid blastocyst always attached itself by the embryonal pole, so here that. pole was the first to enter, and the embryo lay on the deep side of the blastocyst in immediate proximity to the site of formation of the definitive placenta.

Certain features, distinctive of the anthropoids, were to be regarded as the direct outcome of this process of interstitial implantation, and consequently as purely secondary specializations. These included differentiation of a decidua capsularis from the decidual tissue covering the blastocyst; formation round the very early blastocyst of a complete enveloping network of syncytiotrophoblast, possessing in even more marked degree than that of the pithecoids destructive and penetrative properties; and development from the chorion of the older blastocyst of a more or less uniform covering of chorionic villi. In the blastocyst itself formation of the extra-embryonal mesoderm apparently took place at such an early period that it. was able to fill the minute cavity of the blastocyst completely as a delicate cellular tissue in which only later the coelomic cavity appeared.

Apart from these adaptive specializations, the anthropoid developed along the. lineslaid down in the catarrhine stock, and as a result of the atrophy of the chorionic villi originally related to the decidua capsularis and the growth of those related to the decidua basalis, formed a single discoidal placenta, the homologue of the primary placenta of the catarrhine, and differing from that only in minor details and in the rather more individualized character of its foetal chorionic villi. Of the genetic relationship of the anthropoid apes and man, and of these to, the catarrliine stock, concluded Professor Hill, there could be no question on embryological-grounds.

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 19) Embryology Paper - The developmental history of the primates. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Paper_-_The_developmental_history_of_the_primates

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G