Paper - Observations on the origin of the Mullerian groove in human embryos

| Embryology - 27 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Falconer RI. Observations on the origin of the Mullerian groove in human embryos. (1951) Carnegie Instn. Wash. Publ. 611, Contrib. Embryol., .

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Observations on the Origin of the Mullerian Groove in Human Embryos

Contributions To Embryology, No. 229

Robert I. Faulconer

Department of Embryology, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Baltimore

With one plate and one text figure

Introduction

The human Müllerian duct or paramesonephric duct (Frazer, 1940; Hamilton et a1., 1945; Gardner et al., 1948) arises directly from an invagination of the coelomic epithelium at the cranial end of the Wolffian body. The site of invagination has been described by modern workers and in current textbooks of embryology (Tandler, 1913; Hunter, 1930; Arey, I946; Patten, 1946) as the lateral margin of the Wolffian body. Textbooks generally depict a clearly localized invagination occurring on the dorsolateral surface of the Wolffian body, as seen in figure I, but offer no discussion of variations in the site. Shikinami (1926) in his detailed description of the form of the Wolffian body in human embryos of 4.5 to 23 mm. mentions the Müllerian duct only briefly, and gives no details concerning the formation of the ostium. The absence of exact information on this point prompted an investigation of the position of the Müllerian groove in a series of human embryos, with the purpose of clarifying this important detail of development and considering any bearing it might have on the origin of the duct and its derivatives.

It was soon evident that the site of the Müllerian groove is not constant in relation to the cranial end of the Wolffian body, but is subject to much variation. The specimens examined revealed groove formation on all surfaces of the Wolffian body. These sites of invagination are designated as (I) dorsolateral, (2) lateral, (3) ventral, and (4) ventrolateral.

The embryos used in this study are from the collection of the Department of Embryology, Carnegie Institution of Washington, and were selected as representing common variants with respect to the site of origin of the duct. All specimens were studied from complete serial sections, and are in excellent histological condition for a morphological study of this sort. Pertinent information for each embryo is presented in table 1, in which crown-rump length has been corrected in accordance with Streeter’s adjustments for developmental horizons xvi, xvii, and xviii (Streeter, 1948). This circumstance will explain any discrepancy in statements as to length between this report and previous ones in which these embryos have been cited.

Table 1 List of Embryos and Site of Invagination of the Ostium

| Carnegie Number |

Streeter Horizon |

Crown Rump Length |

Plane of Section and thickness (micron) |

Figure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | |||||

| 623 | XVII | 10.1 | Trans. 20 | |||

| 6517 | XVI | 10.5 | Trans. 8 | Lateral | Lateral | |

| 1836 | XVI | 11.0 | Trans. 20 | Ventrolateral | Ventrolateral | 2 |

| 6524 | XVIII | 11.7 | Trans. 10 | Ventral | Dorsolateral | 3, 4 |

| 6521 | XVII | 13.2 | Trans. 8-18 | Dorsolateral | Dorsolateral | 1 |

| 6520 | XVII | 14.2 | Trans. 10 | Ventral | Dorsolateral | 5 |

| 6527 | XVIII | 14.4 | Trans. 15 | Ventral | Ventral | 6, 7 |

Observations

The primordium of the Müllerian duct is said by Felix (1912) to make its appearance on the summit of the urogenital fold in embryos of 10.0 mm. crown rump length. His observation was confirmed in this study. The primordium was first seen in the 10.1-mm. embryo, as a characteristic thickening of the epithelium covering the lateral surface of the Wolffian body near its anterior end. The earliest indication of invagination was found in the same position in the 10.5-mm. embryo. Here a slight depression of the thickened area was present, sharply distinguished from the surrounding epithelium b tall dark-staing P Y 2 ing, columnar cells in and immediately adjoining the groove.

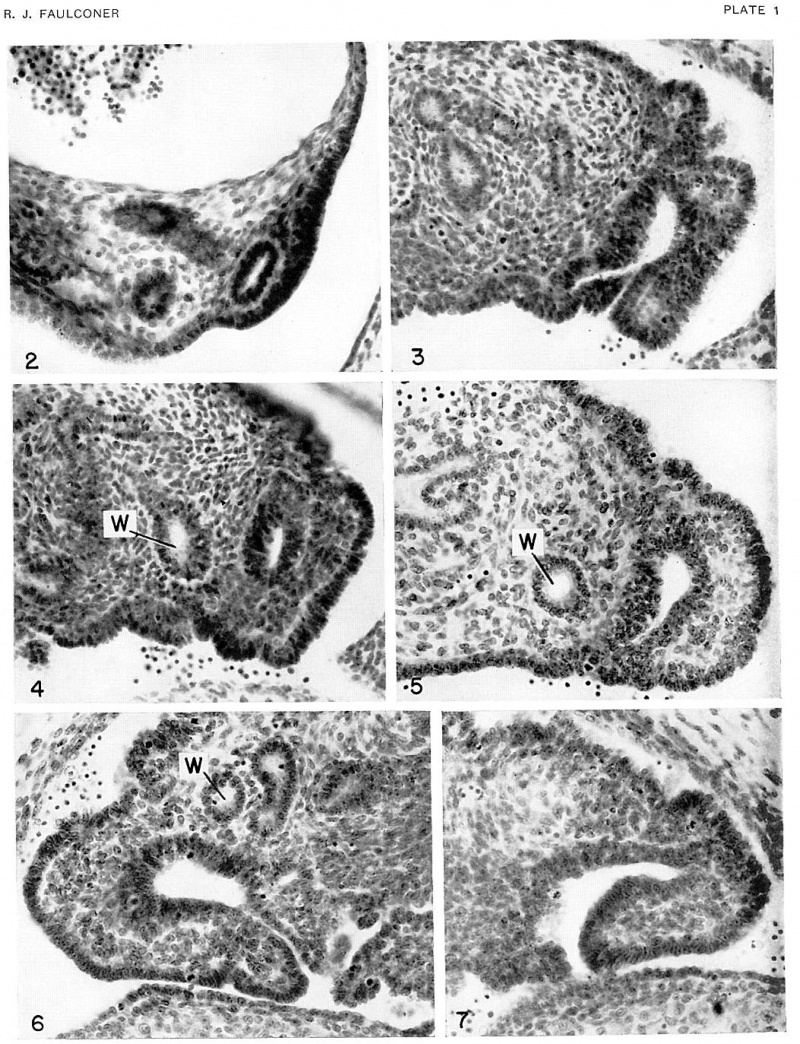

The 11.0-mm. embryo has a ventrolateral Müllerian groove and duct forming on each V\/olflian body. The posterior cardinal veins happen to be unusually large at this level, and oceu most of the cranial end of in the manner usually represented as the characteristic pattern of development (fig. I). The duct is formed by fusion of the dorsal and ventral lips of the groove posterior to the ostium. Following this fusion, the duct occupies a deeper position in the stroma of the Wolffian body, but is always lateral to the Wolffian duct.

In the 14.2-mm. embryo an invagination of the ventral surface, extending through two-thirds of the thickness of the right Wolffian body, is present. The the Wolffian body on either side, save for the ventrolateral region (fig. 2, pl. 1).

Fig 1. Dorsolateral invagination of the ostial region of the Müllerian groove on both sides in a 13.2-mm embryo. This location is usually described as “normal." Embryo no. 6521. X60.

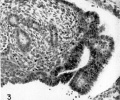

In the 11.7-mm. embryo, ostium and duct formation are well advanced. The cranial end of the right Müllerian groove appears as an irregularly folded thickening continuous with the ventral surface of the Wolffian body (fig. 3, pl. 1). As the invagination progresses caudalward it deepens and occupies a medial position on the ventral surface, until it eventually closes by fusion of the lateral and medial lips of the groove (fig. 4, pl. 1). The Müllerian groove on the opposite side of this specimen is, by contrast, dorsolateral in position.

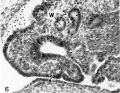

The 13.2-mm. embryo shows symmetrically on either side a dorsolateral groove and duct, forming duct formed is somewhat larger than usual, and about twice the diameter of the Wolffian duct (fig. 5, pl. 1). The left Müllerian groove and duct in this specimen are formed, on the other hand, by a dorsolateral invagination as in figure 1.

The 14.4-mm. embryo shows a wide area of columnar epithelium anterior to the ostium on either side, covering the ventral surfaces of both Wolffian bodies near their cranial ends. As the sections are followed caudalward, a deep ventral invagination of the columnar epithelium is apparent bilaterally (figs. 6, 7, pl. 1). The narrow, deep groove on the ventral surface of the left Wolffian body is lined with a single layer of columnar epithelium through the greater part of its length, and its structure is suggestive of a nephrostomal canal. Farther back, where the duct is completely closed over, the resulting lumina are markedly larger in diameter than those of the Wolffian ducts.

Discussion

In recent times the opinion has been prevalent that the ostium of the Müllerian duct in amniotes arises from the invagination of a special localized area of coelomic epithelium. With regard to human development this view has been quite general. Forbes (1940) has reviewed the known data on the development of the oviducts in reptiles. He demonstrated the development of the ostia in Alligator nzissisxippicrrsis from the coelomic epithelium of the dorsolateral surfaces of the Wolffian bodies by an invagination of these surfaces. According to Forbes, a similar mode of development is found in other reptiles which have been studied.

Lillie (1919) described the formation of the Müllerian duct in the chick. He found that the duct begins as a groove in a specialized area of thickened epithelium, on the lateral and dorsal surfaces of the Wolffian body. The cranial end of the groove re— mains open to form the abdominal ostium, while the caudal extremity closes over as a duct and grows backward in the stroma of the Wolffian body. Lillie recognized that the caudal growth of the Müllerian duct was closely parallel to that of the Wolffian duct at its inception, but considered the two duct systems to be growing independently. The subsequent development of the oviducts of female birds is modified by a regression of the right duct; only the left oviduct and left ovary are functional at maturity.

The coelomic epithelium which forms the Müllerian ostia of mammals has at various times been associated with the site of degenerate pronephric or mesonephric nephrostomes (e.g. Brambell, 1927), but until recently no investigator has demonstrated this relationship satisfactorily in any mammal. Burns (1941) described in the opossum, Didclp/zyr vi:-giriiztrza, the homology of a series of primitive epithelial rete cords and canals in the anterior genital ridge with the ostium of the Müllerian duct. He then suggested the probable derivation of these structures from a series of nephrostomes.

Streeter (1948), in speaking of the precise area on the Wolffian body which invaginates to form the ostium of the human Müllerian duct, said, “This area is regarded by some investigators as a reconversion of unused pronephric epithelium.” The derivation of the ostium of the Müllerian duct from epithelium of pronephric origin appears unlikely for the following reasons: The human proncphros is a rudimentary and imperfect structure. It appears in the L7-mm. embryo, has reached its caudal limit of extension at 2.5 mm. (attaining the level of the fourteenth somite), and has disappeared altogether at 5 mm. At its greatest extent it consists of but seven to eight tubules and never reaches farther caudalward than the first thoracic segment. The Müllerian ostium is formed at the level of the third and fourth thoracic segments, a level never attained by the pronephros.

Mesonephric tubules, on the other hand, may be recognized at the level of the fifth cervical segment. If the Müllerian ostium in human embryos is derived from “unused” nephrostomal epithelium, it would more probably be of mesonephric than of pronephric origin. No observation, however, clearly indicating the direct derivation of human ostia from nephrostomal epithelium has been reported.

The marked variations in the site of the Müllerian groove, as reported in this paper, indicate that the formation of the Müllerian duct is potentially the function of a wide area of specialized epithelium at the cranial end of the Wolffian body. The frequent occurrence of ventrolateral and ventral sites of invagination for the Müllerian groove is, however, suggestive of the conversion of nephrostomal epithelium, since it is in this territory that rudimentary nephrostomalucanals might be expected. It is not to be regarded at present as more than this.

Summary

- The site of invagination of the Müllerian groove in human embryos varies greatly in its relation to the surface of the Wolffian body. The invagination may occur on the dorsolateral, lateral, ventrolateral, or ventral surface of the Wolffian body, always near the anterior end, and may differ in this respect on opposite sides in the same embryo.

- The site of invagination is an area of specialized coelomic epithelium of variable or irregular distribution which may represent the site of one or more mesonephric nephrostomes. Circumstantial evidence in support of this opinion is presented.

I am indebted to the Department of Embryology of the Carnegie Institution of Washington for access to the collection of human embryos and the use of laboratory facilities. I also wish to thank members of the technical and professional staffs for advice and assistance during this study, especially Dr. R. K. Burns, who has given generously of his time and counsel.

Literature Cited

AREY, L. B. 1946. Developmental anatomy. 5th ed., 616 pp. Philadelphia.

BRAMBELL., F. \V. R. 1927. The development and morphology of the gonads of the mouse. II. The development of the Wolffian body and ducts. Proc. Roy. Soc. London, B, vol. 1oz, pp. 206-221.

BURNS, R. K., JR. 194x. The origin of the rete apparatus in the opossum. Science, vol. 94, pp. 142-144.

FELIX, W. 1912. The development of the urinogenital organs. In Keibel and Mall, Manual of human embryology, vol. 2, chap. 9. Philadelphia.

FORBES T. R. 1940. Studies on the reproductive system of the alligator. IV. Observations on the development of the gonad, the adrenal cortex, and the Müllerian duct. Carnegie Inst. Wash. Pub. 518, Contrib. to I£mbryol., vol. 28, pp. 129-155.

FRAZER, I. E. 1940. A manual of embryology. 523 pp. London.

GARDNER, G. H., R. R. GREENE, and B. M. I’r.et<n.-t.\t. 1948. Normal and cystic structures of the broad ligament. Amer. Iour. Obstet. and Gynecol., vol. 55, pp. 917-939.

HAMILTON, W. L, I. D. Born, and H. \V. Mosswtx. 1945. Human embryology. 366 pp. Baltimore.

HUNTER, R. H. 1930. Observations on the development of the human female genital tract. Carnegie Inst. Wash. Pub. .314, Contrib. to Embryol., vol. 22, pp. 91-107.

LILLIE, F. R. 1919. The development of the chick. 472 pp. New York.

PATTEN, B. M. 1946. Human embryology. 776 pp. Philadelphia.

SHIKINAMI, I. 1926. Detailed form of the Wolffian body in human embryos of the first eight weeks. Carnegie Inst. Wash. Pub. 363, Conlrib. to Embryol., vol. 18, pp. 49-61.

TANDLER, J. 1913. Entwickelungsgeschiehte und Anatomic der \\'eil)licl1cn Genitalien, part 1, sec. II, pp. 5-10. Wiesbadcn.

Plate 1

Fig. 5. Large Müllerian duct formed by the invagin:1 tion of the ventral surface of the right Wolffian body in the 14.2 mm embryo. Note the smaller Wolffian duct (W) medial to the Müllerian duct. Embryo no. 6520. X300.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Links: fig 1 | plate 1 | fig 2 | fig 3 | fig 4 | fig 5 | fig 6 | fig 7 | Uterus Development | Genital Development

Reference

Falconer RI. Observations on the origin of the Mullerian groove in human embryos. (1951) Carnegie Instn. Wash. Publ. 611, Contrib. Embryol., .

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 27) Embryology Paper - Observations on the origin of the Mullerian groove in human embryos. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Paper_-_Observations_on_the_origin_of_the_Mullerian_groove_in_human_embryos

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G