Book - Developmental Anatomy 1924-12

| Embryology - 12 Mar 2026 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Arey LB. Developmental Anatomy. (1924) W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Ectodermal Derivatives

Chapter XIII The Integumentary System

The contribution of ectoderm to the front part of the oral and nasal cavities, and specifically to the development of teeth, tongue, and salivary glands, is described in earlier chapters. Here will be presented the histogenesis of the skin and the development of its accessory epidermal structures. The integument is a double-layered organ; only its epithelium is derived from eetoderm, whereas the fibrous corium is mesodermal.

The Skin

The Epidermis

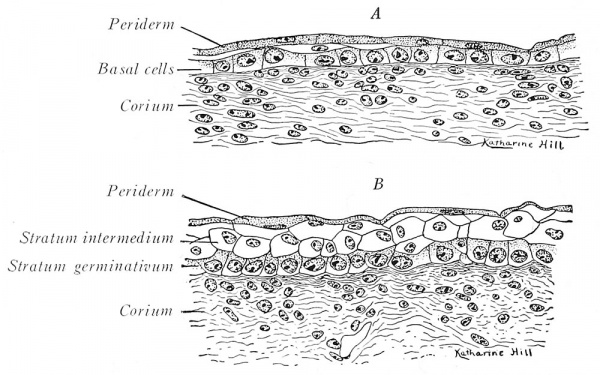

The embryonic ectoderm is originally a single sheet of cuboidal cells (Fig. 212), but, at the end of the first month, it consists of two layers. The outer, somewhat flattened cells compose the transient periderm; the hasal cells, of cuboidal or low columnar shape, are the reproducing elements which gradually give rise to new strata above (Fig. 229 A).

Fig. 229. Sections of the integument from a three-months - fetus (Prentiss). X 440 A. From the neck, showing at the right a two-layered epidermis and at tlie left the beginning of an intermediate layer; B. from the chin, w'ith three well -developed cjudermal layers.

During the third and fourth months, the epidermis is typically threelayered, an intermediate stratum being interposed between the basal and periderm cells (Fig. 220 /?). After the fourth month, the epidermis becomes highly stratified. The inner layers of actively dividing cells then constitute the definitive stratum germinativum. The outer layers cornify progressively toward the surface. Thus, above the germinative cells is the thin stratum granulosum, containing keratohyalin granules. Next higher, lies the clear stratum lucidum whose fluid, eleidin content is supposed to represent softened keratohyalin. Still nearer the surface, the thickened ectoplasm becomes cornifled, and in the cytoplasm a fatty substance collects; these gradually flattened cells comprise the stratum corneum.

.When the hairs emerge, at about the sixth month, they do not penetrate the outer periderm of the epidermis, but lift it off. Hence, in mammals, this layer is known also as the epitrichuim (layer upon the hair). Desquamated epitrichial and epidermal cells mingle with cast-off lanugo hairs and sebaceous secretions to form the pasty vernix caseosa that smears the fetal skin. Pigment granules appear soon after birth in the cells of the stratum germinativum; these granules are probably elaborated by the cytoplasm. Negro infants are quite light in color at birth, but within six weeks their integument reaches the final degree of pigmentation.

The Derma or Corium

The origin of the fibrous layers of the chick - s integument may be traced to that lateral portion of a mesodermal segment termed the cutis plate or dermatome (Fig. 212). It is now claimed that mammals lack a dermatome and that the region usually so designated really is a part of the myotome. In this event, the connective-tissue corium differentiates directly from the mesenchyme subjacent to the epidermis. At about the end of the third month, a distinction between the compact corium proper and the looser subcutaneous tissue becomes recognizable. From the corium, papillae project into the germinative stratum.

Anomalies

The deposition of pigment in the epidermis and elsewhere may fail {albinism), or be over-abundant {melanism). The defects of pigmentation sometimes affect local areas only. Navi are either pigmented spots Cmoles - ), or purple discolorations {'birthmarks - ) caused by cavernous vascular plexuses in the corium. Ichthyosis represents an excessive thickening of the stratum corneuni. In severe cases, horny plates, separated by deep cracks, are formed. Dermoid cysts (p. 156), resulting from epidermal inclusions, are not infrequent along the lines of fusion of embryonic structures (e.g., branchial grooves, mid-dorsal and mid-ventral body wall).

The Nails

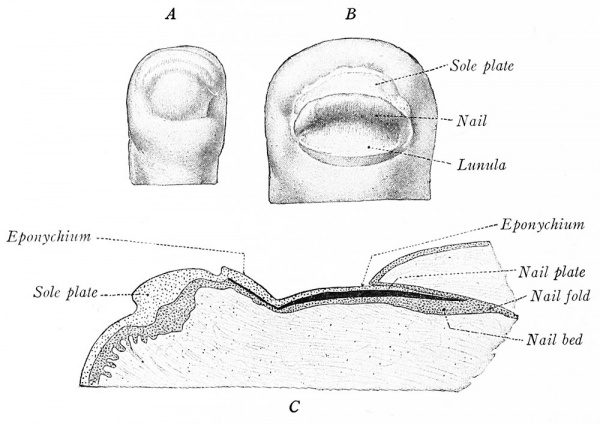

Nails are modifications of the epidermis that correspond to the claws and hoofs of lower mammals. The nail anlage is recognizable in fetuses of 10 weeks as an epidermal, pouch-like fold that soon extends from the proximal border of the future exposed plate almost to the articulation of the terminal phalanx (Fig. 230 C) this proximal nail fold also continues laterally on either side as the lateral nail folds (Fig. 230 A, B).

Fig. 230. The development of the human nail (Kollman). A, 10 weeks (X 20); B, 14 weeks (X 1,3); C, longitudinal section at 14 weeks (X 24).

The material of the nail is developed in the lower lamina of the proximal nail fold (Fig. 230 C). Certain of the epidermal cells, which, according to Bowen, represent a modified stratum lucidum, develop keratin fibrils during the fifth fetal month. These appear without the preliminary keratohyalin stage, as is the case in ordinary epidermis. The cells flatten and form the compact mass of which the nail plate is composed. Thus, the nail substance differentiates in the proximal nail fold as far distad as the outer edge of the Iunula (the whitish crescent at the base of the adult nail). Beyond the lunule, the underlying epidermis takes no active part in development. The stratum corneum and periderm of the epidermis for a time cover completely the free nail and are termed the eponychium (Fig. 230 C). In late fetuses this is lost, but portions of the horny layer persist as the curved rim of epidermis which adheres to the base of the adult nail. During life the nail constantly grows at its base (proximally), is shifted distally over the nail bed, and projects at the tip of the digit. The coriuni throws its surface of contact with the nail into parallel longitudinal folds that produce the characteristic ridging.

The Hair

Hairs are specialized epidermal gowths. The earliest begin to develop at the end of the second month on the eyebrows, upper lip, and chin; those of the general integument appear at the beginning of the fourth month.

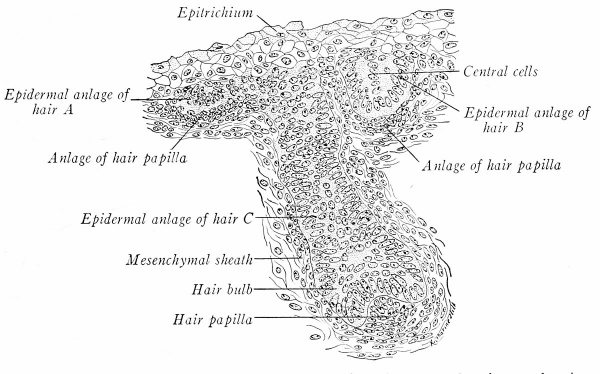

The first evidence of a hair anlage is the crowding and elongation of a cluster of germinative cells (Fig. 231, A). Their bases sink bud-like into the corium, and active proliferation soon produces a cylindrical epithelial plug (Fig. 231, B , C). This hair anlage consists of an outer wall of columnar cells, continuous with the basal layer of the epidermis, and an internal mass of polyhedral cells. About the whole is a mesenchymal sheath, and at its base the mesenchyme condenses into a mound-like papilla.

Fig. 231. Section through the facial integument of a three-months - fetus, showing three stages in the early development of hair (Prentiss). X 330.

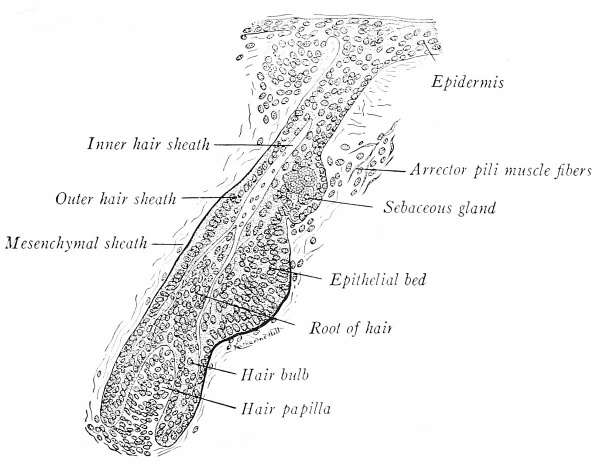

Fig. 232. Longitudinal section through a developing hair from a five and one-half months - fetus (Stohr in Prentiss). X 220.

As development proceeds and the hair anlage pushes deeper into the corium, its base enlarges into the bulb which becomes moulded over the papilla (Fig. 232). The actual hair substance is a proliferation from the basal epidermal cells next the papilla. These cells give rise to an axial core, destined to become the inner sheath and shaft, which grows toward the surface (Fig. 232). Entirely distinct are the peripheral cells of the original anlage which constitute the outer sheath.

The hair grows at its base and is pushed up through the central cells of the primordial downgrowth. Above the level of the bulb, the cells of the hair shaft cornify and differentiate into an outer cuticle, middle cortex, and central, inconstant medulla. Two swellings of the outer hair sheath appear on the lower side of the obliquely directed follicle. (Fig. 232). The upper of these becomes the associated sebaceous gland; the deeper swelling is the epithelial bed, a region of rapid mitosis that contributes to the growth of the hair follicle. Mesenchymal tissue near the epithelial bed transforms into the smooth fibers of the arrcctor pili muscle. Pigment granules develop in the basal cells of the hair and cause its characteristic coloration.

The first generation of dense, silky - lanugo - hairs are short-lived, all except those covering the face being cast off soon after birth. The coarser, replacing hairs develop, at least in part, from new follicles. Thereafter, hair is shed and regenerated periodically throughout life.

Anomalies

Hypertrichosis refers to excessive hairiness which may be general or local, as in exhibited - hairy monsters. - In the rare hypotrichosis, the congenital absence of hair is usually associated with defective teeth and nails.

Sebaceous Glands

Nine-tenths of all sebaceous glands accompany hairs but independent ones occur also, such as those around the nostrils, anus, and eyelids. They appear first in the fifth month as solid buds of the epidermis, especially that of the hair follicles (Fig. 232). The anlage becomes a lobulated sac. A lumen forms by the fatty degeneration of the central cells, and the resultant oih" secretion is an important constitutent of vernix caseosa (p. 231).

Sweat Glands

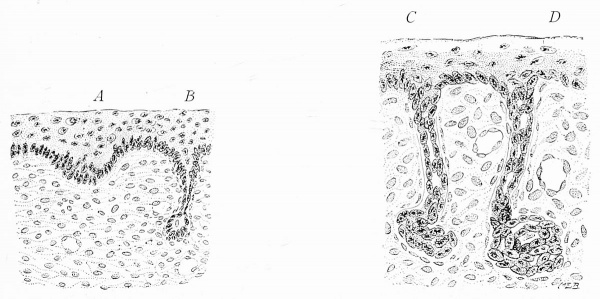

Sudoriferous glands begin to develop in the fourth month from the epidermis of the finger tips, the palms of the hands, and the soles of the feet. They are formed as solid downgrowths from the epidermis, but differ from hair anlages in being more compact and in lacking the mesenchymal papillie at their bases (Fig. 233, A, B). During the sixth month the simple cords coil, and, in the seventh month, their lumina appear (Fig. 233, C, D). The inner layer of eells forms the gland cells, while the outer cells become transformed into smooth muscle fibers, which, accordingly, are ectodermal. In the axilla, eyelids, and external acoustic meatus the sweat glands are large and branched.

Fig. 233. Vertical sections of the integument, illustrating four stages in the development of a sweat gland (adapted from Kollman). A, B, Four months; C, D, seven months.

Mammary Glands

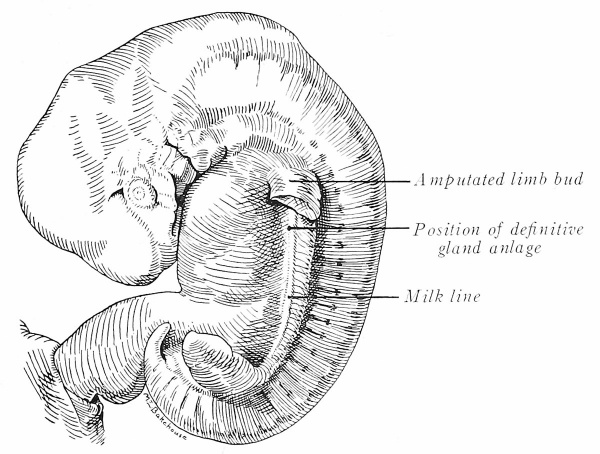

Mammary glands are peculiar to mammals. In embryos of about 9 mm. paired ectodermal thickenings extend lengthwise between the bases of the limb buds (Fig. 234). This linear ridge is the milk line. In man it often is inconspicuous except in the pectoral region, but in lower mammals, like the pig, that have serially repeated glands, a prominent thickening reaches from axilla to groin (Fig. 389).

Fig. 234. Human embryo of 13.5 mm. with a prominent milk line (after Kollman). X 5.

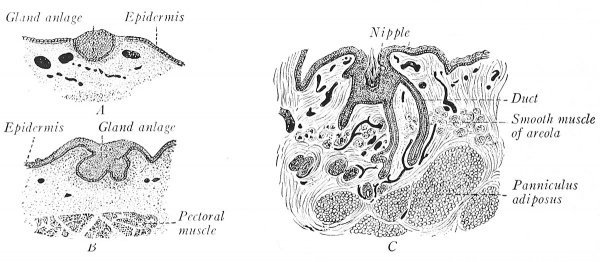

Each human mammary gland begins as a thickening and downgrowth from the epidermal milk line in the region of the future breast (Fig. 235). During the fifth month, from 15 to 20 solid cords bud off {B). These anlages of the milk ducts branch in the mesenchymal tissue of the corium, hollow out, and eventually produce the alveolar oid pieces (C). Where the milk ducts open on the surface the epidermis is elevated to form the nipple, but this may be delayed until after birth. The glands yield a little secretion ( - witch milk - ) at birth; they enlarge rapidly at puberty and are further augmented during pregnancy, while two or three days after parturition they become functionally active.

The mammary glands are regarded by most authorities as modified sweat glands. This homology is made because their development is similar, and because in the lower mammals their structure is the same. Rudimentary mammary glands (areolar glands of Montgomery), which also resemble sweat glands, occur in the areola about the nipple. In many mammals, numerous pairs of mammary glands are developed along the milk line (pig; dog) ; in some a single pair occurs in the pectoral region (primates; elephant); in others, they are confined to the inguinal region (sheep; cow; horse).

Fig. 235. Sections representing three stages in the development of the human mammary gland (Tourneux). A, Two months; B, four months; C, seven months.

Anomalies

Supernumerary mammary glands (hypermaslia) or nipples (liy perihelia) between the axilla and groin are common. These represent independent differentiations along the primitive milk line, such as occur normally in some mammals.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

| Developmental Anatomy 1924: 1 The Germ Cells and Fertilization | 2 Cleavage and the Origin of the Germ Layers | 3 Implantation and Fetal Membranes | 4 Age, Body Form and Growth Changes | 5 The Digestive System | 6 The Respiratory System | 7 The Mesenteries and Coelom | 8 The Urogenital System | 9 The Vascular System | 10 The Skeletal System | 11 The Muscular System | 12 The Integumentary System | 13 The Central Nervous System | 14 The Peripheral Nervous System | 15 The Sense Organs | C16 The Study of Chick Embryos | 17 The Study of Pig Embryos | Figures |

|

Reference

Arey LB. Developmental Anatomy. (1924) W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia.

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2026, March 12) Embryology Book - Developmental Anatomy 1924-12. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_Developmental_Anatomy_1924-12

- © Dr Mark Hill 2026, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G