Book - An Atlas of Topographical Anatomy 2

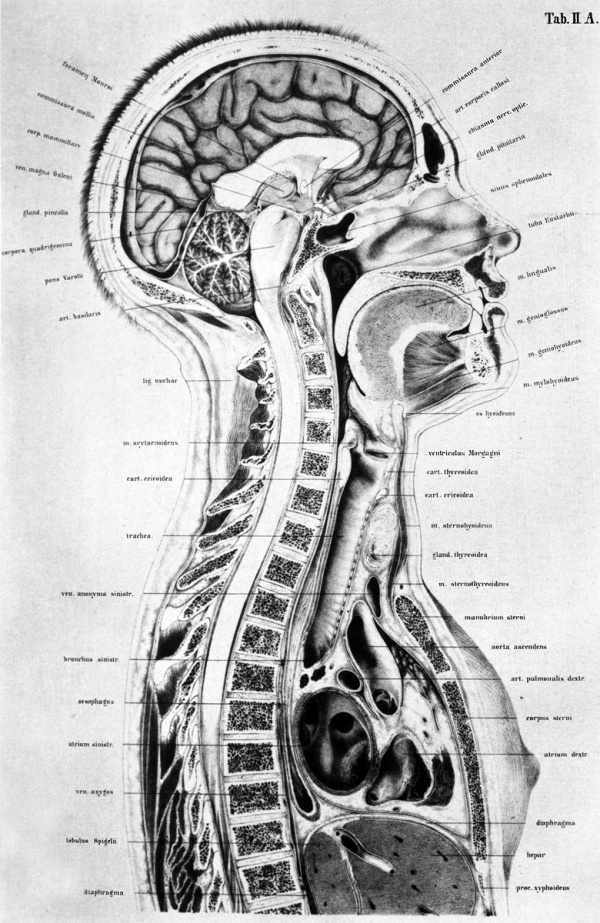

II. Sagittal section of the body of a female

| Embryology - 27 Feb 2026 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Braune W. An atlas of topographical anatomy after plane sections of frozen bodies. (1877) Trans. by Edward Bellamy. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

- Plates: 1. Male - Sagittal body | 2. Female - Sagittal body | 3. Obliquely transverse head | 4. Transverse internal ear | 5. Transverse head | 6. Transverse neck | 7. Transverse neck and shoulders | 8. Transverse level first dorsal vertebra | 9. Transverse thorax level of third dorsal vertebra | 10. Transverse level aortic arch and fourth dorsal vertebra | 11. Transverse level of the bulbus aortae and sixth dorsal vertebra | 12. Transverse level of mitral valve and eighth dorsal vertebra | 13. Transverse level of heart apex and ninth dorsal vertebra | 14. Transverse liver stomach spleen at level of eleventh dorsal vertebra | 15. Transverse pancreas and kidneys at level of L1 vertebra | 16. Transverse through transverse colon at level of intervertebral space between L3 L4 vertebra | 17. Transverse pelvis at level of head of thigh bone | 18. Transverse male pelvis | 19. knee and right foot | 20. Transverse thigh | 21. Transverse left thigh | 22. Transverse lower left thigh and knee | 23. Transverse upper and middle left leg | 24. Transverse lower left leg | 25. Male - Frontal thorax | 26. Elbow-joint hand and third finger | 27. Transverse left arm | 28. Transverse left fore-arm | 29. Sagittal female pregnancy | 30. Sagittal female pregnancy | 31. Sagittal female at term

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

THIS section was made on the body of a finely formed woman (twenty five years of age), which was brought into the dissecting room immediately after death by hanging. The arteries were injected with paint, the body laid on the back and frozen, and the details of the section carried out as in the last case.

The uterus was found to contain a foetus of, probably, the eighth week. All the organs were normal. The stomach and intestines were tolerably empty ; the transverse colon was moderately distended with flatus, and the rectum with fasces. The bladder was contracted, and as no urine had flowed from it during the transport of the body, it was probably empty at the time of death.

The section was carried from below upwards, chiefly in order to divide the pelvis in the middle line, and was, on the whole, very successfully directed. The articulation of the symphysis was opened, and so also were the urethra and lowest part of the rectum.

On the other hand, the uterus, which lay somewhat on the left side, was cut through in its right half, yet so near the middle line that it was necessary to remove a thin slice only in order to show the canal of the cervix throughout its extent. The spinal canal was opened throughout, and very near to its middle line.

It will be noticed, from the appearance of the dorsal portion of the cord, that at the lower part of the thorax the vertebrae are cut to the right of the middle line, and from the appearance of the great vessels of the abdomen, that the section passes through the diaphragm between the caval and the aortic apertures. The inferior cava is entirely removed with the right half of the body, and a transverse section only of the left common iliac vein is seen ; the abdominal aorta, on the other hand, is completely shown, with the right common iliac artery divided.

In the thorax the saw has passed exactly in the middle plane ; neither lung is seen and neither pleural sac. As regards the tongue, a small lamina only had to be removed to expose its mesial plane. The cerebrum was not cut exactly in the middle line, so that about one tenth of an inch of the dura mater had to be removed in order to expose the longitudinal sinus and to accurately halve the brain, which had been in the meanwhile hardened with spirit.

Before I enter upon the chief points of importance in this plate or describe the pelvic viscera, I shall point out the general relations of the parts, commencing with the vertebrae.

The spinal column shows a very beautiful curve, which contrasts favorably with that in Plate I. On account of the slight bending backwards of the head the cervical vertebrae do not project so far forwards, and the dorsal spine does not curve backwards so considerably, but passes more gradually into the convexity of the lumbar curve.

If a line be drawn parallel with the long axis of the body, commencing in the region of the occipito-atloid articulation, and then passing through the posterior border of the odontoid process of the second cervical vertebra, it would touch the last cervical and first dorsal vertebra (in Plate I it touches the three lower cervical), and pass down close behind the promontory. The line passing nearly through these points is, according to Weber, the line of gravity.

The inclination of the pelvis is 58 (less than that of the male in Plate I, which is 60).

The slight projection of the promontory is characteristic of the female spine, as opposed to that of the male, and so also is the more abrupt direction of the symphysis pubis. It is evident from this circumstance that the conditions are more favorable for the expulsion of the child, which thus glides the more easily downwards on to the promontory from the more abrupt surface of the symphysis. It is repeatedly contested that the axis of the symphysis (by which is understood the direction of the greatest length of the joint) is more abrupt in the female than in the male, and from this an impediment to parturition has been sought. I am not able to declare whether in this particular a constant difference exists between the male and female pelvis. From a series of sections on frozen bodies I have, however, found this relation over and over again, as this and the first plate show, and I might therefore direct the attention of gynaecologists to this point, for I am unable as yet to give any decided opinion upon it.

The conjugate diameter is very large,* 4' 8 inches. The pelvis, on the whole, is wide, but is not otherwise abnormal. There is not much to remark as regards the head; the individual parts are the same as in Plate I. It is fortunate that the mouth was firmly closed, as the two incisor teeth shut upon one another like the blades of a pair of scissors. The tongue completely filled up the mouth. In a transverse section of the tongue a shallow furrow is generally noticed at its back, which passes from before backwards, a narrow space being left between the tongue and hard palate ; hence it must be assumed that the middle line of the tongue was not in this case exactly in the line of section. The oesophagus, in which was some undigested food, admits of delineation throughout its entire extent, but on account of the shading, it is not satisfactorily represented in its original position; against the third dorsal vertebra the shading is not intense enough to show its deep excavation. At the level of the sixth and seventh dorsal vertebrae, on account of the small piece cut off, more of the oesophagus lies on the right half of the body, and consequently its course forms a flat $-curve i n the frontal plane.

In front of the trachea lies in section a considerably developed thyroid body, which causes a slight bulging forwards of the neck. Beneath this lies the left innominate vein, and close to it are the remains of the thymus gland ; behind the vein is the ascending aorta with a section of the innominate artery. The course of the innominate artery with regard to the trachea is of considerable surgical importance. An incision made in the mesial line of the neck between the thyroid body and the upper border of the sternum would reach the vessel as it lies on the trachea. Ligature of this vessel has hitherto not been successful, owing to shortness of the trunk (from one inch to an inch and three fifths). It is not to be wondered at that the conditions for the formation of a firm coagulum are here unfavorable. It must also be borne in mind that the incision made to search for the vessel is, like that made in tracheotomy, below the thyroid body, and that at the lower end of the wound the left innominate vein may be met with. The trachea, which when extended lies on the anterior surface of the oesophagus, divides into its two bronchi in front of the fourth dorsal vertebra, as is shown in the section represented in Plate I.

I was much surprised by the apparent shortness presented by the trachea in the section of a frozen body made with the head depressed, and by its becoming very considerably extended, when at the commencement of thawing I reinstated the head in its normal position. It is owing to this extensibility of the trachea due solely to the elastic tissue between the cartilaginous rings that positions of extensive flexion and extension of the head can be taken up without thereby causing dislocation of the roots of the lungs. Were the trachea a uniformly solid tube it must follow that at each flexion of the head it would be pushed dangerously upon the root of the lung and left auricle, whilst on each abrupt jerking back of the head the thoracic viscera would be dislocated upwards by the sudden drag. Measurements which I have made show that the amount of extensibility of the trachea during flexion and extension of the head is about one inch, and that there is no considerable folding or pinching-up of tissue in its inner wall. This peculiar condition also accounts for the wide gaping of all transverse wounds of the trachea during extension of the head.

Of still further practical importance, particularly with relation to the performance of tracheotomy, is the variation in the relative position of the trachea and the anterior surface of the neck in the different positions of the head. During extreme extension of the head the trachea is brought considerably nearer, the surface of the neck, and is consequently more accessible ; moreover, the field for operation is much more extensive than when the chin is in the usual position of depression. The section given by Pirogoff (1. A, 14, 1 ) is remarkably instructive on this point. Again, with the extension and advancement of the trachea, the arch of the aorta and the innominate artery are drawn somewhat higher, and in this way the latter vessel is rendered more accessible for ligature.

As regards the heart, its left auricle was distended, owing to the injection having entered it from the lungs, thus the appearance presented by these parts is normal. The oval-shaped section of the distended left auricle is seen close to the oesophagus, before the more triangular opening in the right auricle. A small portion of the right ventricle is opened by the section. From both auricles the corresponding ventricles can be seen through the auriculo- ventricular openings ; these parts, after careful cleansing, are shown in their hardened condition. In the left auricle is seen the entrance of the pulmonary veins, in the right the coronary sinus. The sinus, with the valves of Thebesius, are shown in the lowest part of the triangular section of the right auricle. A portion of the valvular apparatus can be seen in the divided arch of the aorta ; behind the vessel lies the right branch of the pulmonary artery. A small portion of the right auricular appendage which was left in the left 'half of the body (also agreeing with the section in Plate I), was removed, so that a considerable space is left in front of the aorta inside the pericardium.

If the section of the thoracic cavity be compared with that of the young man (Plate I) it will at once be observed that the upper border of the manubrium of the sternum is half the depth of a vertebra higher in the male, and about yth of an inch further from the spine than in the female. In the female the upper border of the sternum corresponds with the space between the second and third dorsal vertebrae. The greater capacity of the male thorax is also demonstrated from the fact of the diaphragm reaching to the level of the nbro-cartilage between the ninth and tenth dorsal vertebrae, whereas in the female its highest point corresponds with the upper border of the ninth, and is consequently the depth of an entire vertebra higher. We have to deal here with a well-proportioned though greatly developed female, but as the two subjects were of the same age it will be of great advantage to compare them. It appears that the position of the several parts of the heart in both is nearly similar as regards the mesial line. (In both cases the auricles and a small portion of the right ventricle appear in the section.)

Nothing is seen of the lungs in young persons in such a preparation in consequence of the presence of the thymus gland; in the condition of expiration their anterior edges never reach the middle line, consequently a median vertical section does not expose lung tissue. In old persons, in consequence of the dwindling away of this organ and of the slight capability of contraction of the lungs, they meet one another after death anteriorly ; and, moreover, the right lung frequently overlaps the left half of the body.

On account of the slight distension of the intestines the cavity of the abdomen showed but little prominence, but not, however, an actual in- drawing of the abdominal walls as one observes in sections of bodies which have become emaciated from sickness. In this case, from the amount of fat beneath the skin and in the abdomen it is plain that the individual was well nourished. Also in this particular the circumstances closely resemble those of Plate I, although there is a considerable difference with regard to the depth of the abdominal cavity. In consequence of the greater distension of the stomach and intestines in the male subject, which is manifest from the greater extent of the section through the intestines, and that in the female the arteries were injected and the gravid uterus pushed a portion of the small intestine upwards, the distance of the abdominal wall from the vertebra at the level of the twelfth dorsal vertebra, in this plate, amounts to, nevertheless, 2 inches less, whilst in the region of the umbilicus the depth of the abdominal cavity is much the same in each, viz. about 3'5 inches. It is, moreover, to be borne in mind that in the male spine the concavity of the dorsal region begins lower down, is more decided than in the female, and further, that the bladder in this instance is empty and in the other tolerably full.

The section has so fallen through the abdomen that the diaphragm has been met with between the oesophageal and caval openings more towards the right side of the spine, so that the abdominal aorta is not divided as in Plate I, but remains intact on the upper surface. In order to make the artery more clear for the drawing, only a small layer of cellular tissue was removed so as to render distinct its plastic appearance. At its inferior extremity is the divided right common iliac artery ; nothing is to be seen of the inferior cava (which remains in the right half of the body) but a small portion close to the left common iliac vein. In like manner (as in Plate I) the trunk of the superior mesenteric vein is divided at the point where it, after receiving the splenic vein, courses over to the right side, opposite the pancreas, and passes to the liver as the portal vein. In front of the lower end of this vein is the superior mesenteric artery.

The pancreas, though not so broad as in Plate I, has a similar position at the level of the first lumbar vertebra. The superior mesenteric vein passes through the (lesser) pancreas throughout its extent. The duodenum, which was tolerably empty and flattened by the injected vessels, appears as a narrow cleft in front of the second or third lumbar vertebrae, at the inferior end of the lesser pancreas. In Plate. I, in consequence perhaps of the greater development of the lesser pancreas, it lies somewhat deeper.

A small piece of the lobulus Spigelii of the liver, which is covered by peritoneum, is seen remaining in the left half of the body. The complicated arrangement of the peritoneum in this region can be understood by consulting Plate XV, which represents a transverse section at the level of the eleventh dorsal vertebra, and thus accidentally corresponds to the section which separates both plates.

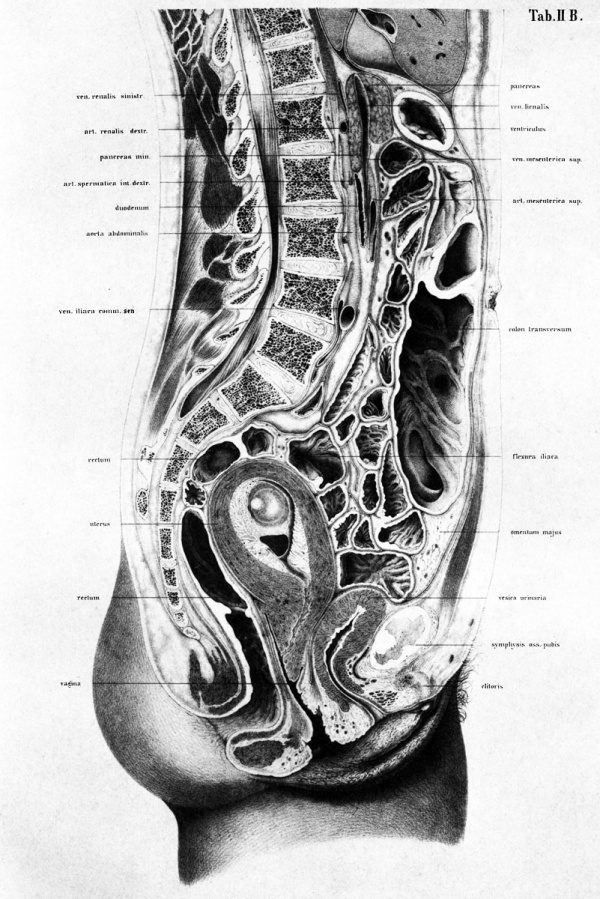

The stomach was empty and contracted, but the transverse colon, which was considerably distended with gas, hung down like a sling, and was therefore divided to a greater length. There is no peculiarity to be noticed in the small intestine. A portion of the ileum is pushed up out of the pelvis by the uterus, and therefore the lumina of the intestines fill up the abdominal cavity higher than in Plate I. We must here consider the relations of the rectum more attentively. It was evenly distended with frozen faecal matter, and was of great calibre. The anus is directed backwards as in the upright position, a direction dependent on the inclination of the pelvis ; but in the sitting position, when the equilibrium of the trunk is maintained by the tuberosities of the ischium, the symphysis is raised .so considerably that the conjugate diameter is nearly horizontal, and the anus takes a direction directly downwards. Above its lowest curve, at the level of the coccyx, is a transverse fold, which is the commencement of the valves of the rectum of Kohlrausch. Higher up the rectum gradually passes over towards the left side, and afterwards it crosses the middle line again by a sharper curve to fall a second time into the plane of section. From the transversely divided lumen of bowel, which lies in front of the third and fourth pieces of the sacrum, the rectum appears again more in the middle line, and following the curvature of that bone, terminates in the iliac flexure. The rectum thus forms a double S curve ; one portion lying in the antero-posterior plane of the body, the other in the transverse. These bendings serve to support the sphincter-apparatus during the pressure of the faecal matter, so that at the time of defecation a resistance is afforded which would not exist were the direction of the rectum vertical. It will be observed also that the name rectum, which has been applied to this portion of the intestine, is incorrect ; it originated from the old representations which were made from undistended intestine and soft preparations.

In front of the rectum, between it and the contracted bladder, is the gravid uterus. Considerable interest is claimed for this section, from the fact of the womb being in a state of gestation corresponding with the end of the second month.

I am unable to say how it happens that the body of the uterus is so sharply bent against its neck and turned backwards, for its tissues are absolutely normal, and according to the statement of Hoist (' Beitrage zur Geburtskunde,' 1 H., Tubingen, 1868, p. 162) at this period of pregnancy anteflexion rather than retroflexion would be expected. I can only with difficulty accept the proposition that the uterus during life had some other position originally, and that directly after death, when the body was placed on its back, it sank down from its own weight. At the same time it must be admitted that the space between the uterus and rectum was previously occupied by small intestine, and yet we cannot imagine that they slid upwards in order to make room for the body of the uterus. The subject presented throughout firm tissues and strong muscles, and there were no signs of a previous pregnancy. The relations of the intestines are normal; no coils lie between the uterus and rectum, or uterus and bladder.

The deep situation of the external orifice of the uterus, from which a firm plug of mucus projects, corresponds with early pregnancy. Later on the uterus rises up out of the pelvis and draws the vaginal portion up with it, so that the external os takes a higher position.

The uterus itself inclined somewhat towards the left side, so that the plane of section passed obliquely through its long axis, and only a small portion of it was removed with the right half of the body.

The hinder lip of the cervix appeared as if it had slipped away, and wanted only a thin slice more to be cut off in order to expose the canal of the cervix throughout its length.

The bag of the amnion was untouched, and the umbilical vesicle was clearly evident. I have removed from the wall of the uterus successive layers so that the individual parts of the ovum may be seen distinctly.

On the inner side of the muscular tissue of the uterus can be seen the decidua vera, consisting of uterine follicles, cellular tissue, and bloodvessels. The round openings of the follicles could be easily seen with the naked eye on the inner and upper surfaces. Above, commencing in the anterior wall of the uterus, the decidual layer is extremely thin, but it gradually increases on the posterior surface, and in the neighbourhood of the internal uterine orifice it is still thicker. Corresponding to the thinnest spots, at about the middle of the fundus, the decidua reflexa is shown as a fold over the triangular clot of blood. It is one of the thin envelopes of the ovum, and is most external. It is formed from the chorion Isevis and the decidua reflexa, and upon it are found remains of epithelium, connective tissue, and rudimentary tufts.

From the position of the effused blood (which is accurately represented) a slender, whitish line runs backwards and upwards, dividing the chorion frondosum from the decidua vera. The portion of the chorion which is shown in the plate contains only tufts and vessels ; it indicates the place of formation of the placenta. In this neighbourhood the umbilical cord is already discernible as it runs deeply downwards.

Inside the chorion was a viscid fluid, in which floated the sac of the amnion, the vitelline duct, and umbilical vesicle. Distinct membranes between the chorion and amnion were not made out in the fluid. The embryo shows the usual curvature of the trunk with the head bent forwards. Its length, from the coccyx to the head as it lay in its original position was about four fifths of an inch, and when stretched out it was about one inch and a fifth.

The cranium was so enveloped by its coverings that the division of the brain could not be seen clearly through them. The nose was small, but already formed. The lateral parts of the oral cavity (the cheeks and lips) were already so developed that the mouth appeared as a circumscribed fissure. The upper and fore arms were flexed and separated ; the hands were discernible and the lower extremities were in a proportionate stage of development. These conditions correspond with the development of an embryo described by Erdl (' Die Entwickelung des Menschen und Huhnchens im Eie,' Leipzig, 1845, taf. iii, 6, iv, 18, ix, 3 and 4).

The umbilical vjesicle is represented too tense and large. It lay on the closed amnion as a flaccid bag, looking like a membranous disc, of the size of a lentil, or about one fifth of an inch in diameter.

The vagina, divided through its anterior and posterior rugae, appears as a narrow fissure, and is continued upwards behind the posterior lip of the external os.

The right sacral ligament of the uterus is seen in the bundles of fibrous tissue here divided. The fibres do not admit of being clearly discerned from the muscular tissue of the uterus, but show themselves merely as a transversely divided bundle, the continuation of which in the fold of Douglas grasped the rectum on both sides and extended to the sacrum. It cannot be accurately defined where the vagina ends and the uterus begins. The muscular fibres of both organs lay so close together, and were so interlaced, that they are represented as being in continuity. It is clear from the plate that the peritoneum stretches further down behind the uterus than in front, and that it covers a small portion of the wall of the vagina. A thin process of fascia is united to this by lax cellular tissue, which permits of a shifting of the rectum and vagina in their mutual distension. I have found the connexion between the bladder and cervix uteri so arranged that the possibility of considerable distension of the bladder, and of the anterior wall of the vagina, and a rising of the uterus would be permitted. The ascent of the base of the bladder is not possible if it were, as is stated by Courty, adherent to the cervix (Courty, ' Maladies de 1' uterus,' Paris, 1866, page 11).

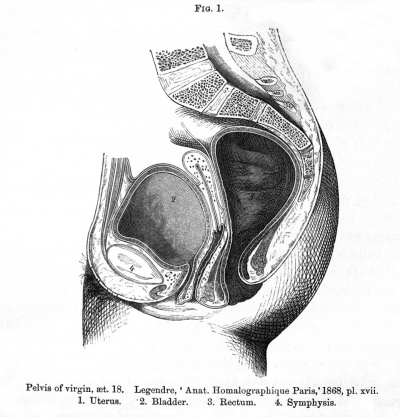

The clitoris is shown with its right crus divided. Behind it, and in front of the urethra, lie the divided blood-vessels of the bulb of the vestibule. The urethra opened of itself after the thawing of the preparation, and is shown in the dilated condition. In the tissue in front of and behind the urethra was found (by means of the microscope) a layer of striped muscular fibre which forms the sphincter of the urethra. I was not able to obtain a well-made female subject for section, nor did I succeed in getting a body affected with well-marked anomalies in as regards the position of the uterus. It is, however, of great practical interest to compare the plane sections of such a body with the plate ; I therefore give a series of reduced copies from Legendre and Pirogoff, with the idea of making this work as complete as possible. The bladder in fig. 1 contained, according to Legendre, nearly one pint of urine. The peritoneum at its reflexion from the bladder was two inches from the symphysis, and its distance behind the uterus from the perineum was 2.08 inches. The conjugate diameter was 4.2 inches ; that of the outlet was 2.4 inches.

Although a decidedly atrophic uterus is here represented, the plate must be accepted, as I sought in vain for a better specimen. The distended bladder has lifted the peritoneum some way from the symphysis, and has pushed the uterus downwards and backwards. The form of the bladder is not that usually found in young persons. The spindle shape which is so characteristic in children persists for some long time, whereas the rounder form is met with in old persons. It is not improbable that Legendre had removed the viscera from the subject the preparation was made from, which would account for no sections of intestines being seen excepting the rectum, as well as for abdominal walls being cut off shorter than the spinal column. Should this have bsen the case, the form he has given to the bladder is explained ; a bladder lying freely is distended in a different manner from one which lies in the closed abdominal cavity, as can be easily proved by experiment. On the other hand, the level of the reflexion of the peritoneum above the symphysis agrees with that given in the young subject which Legendre figures. In young persons only can we reckon that in distension of the bladder so much space would be gained that in extracting a calculus above the symphysis a sufficiently large vertical incision can be made without wounding the peritoneum ; in old persons the space is very limited in a transverse direction. Between the uterus and the rectum no coils of intestine are seen.

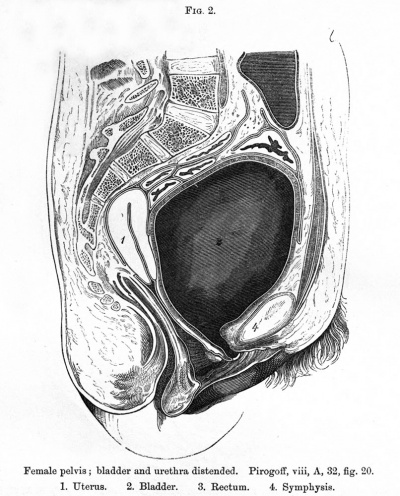

The following plate from Pirogoff merely shows the bladder and urethra fully distended in order to demonstrate the anatomical relations of the high operation and the vestibular incision for stone.

Fig. 1. Pelvis of virgin, set. 18. Legendre, ' Anat. Homalographique Paris,' 1868, pi. xvii. 1. Uterus. 2. Bladder. 3. Rectum. 4. Symphysis.

FIG. 2. Female pelvis ; bladder and urethra distended. Pirogoff, viii, A, 32, fig. 20. 1. Uterus. 2. Bladder. 3. Rectum. 4. Symphysis.

A thorough distension of the bladder left the peritoneum an inch and a half from the symphysis, and by the traction on the anterior wall of the vagina the uterus is drawn upwards and backwards. The conjugate axis is 4.08 inches. The rectum is empty and contracted.

The extent to which the position of the uterus varies with distension and evacuation of the bladder is well shown in figs. 2 and 3. The section in fig. 3 has not gone exactly through the mesial plane, and thus, although the uterus is bisected, the anus and the urethra have escaped division. In fig. 2 we have exactly the opposite conditions, namely, an empty bladder and distended rectum ; consequently the relations of the uterus and vagina are altered. Whereas in fig. 2 the uterus follows the axis of the vagina, in this instance it forms an obtuse angle with it, without, however, being anteverted. No coils of intestine lie between the uterus and rectum. The conjugate diameter is 4.41 inches.

FIG. 3. Female pelvis, set. 35 ; normal ; bladder empty, rectum distended. Pirogoff, iii, A, 21, fig. 3. 1. Uterus. 2. Bladder. 3. Rectum. 4. Symphysis.

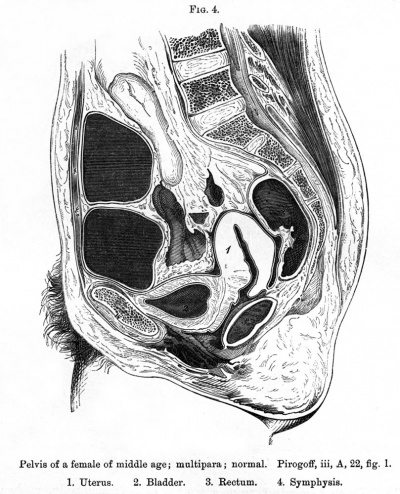

The uterus in fig. 4 with all its connections, was normal, and lay between the moderately distended bladder and rectum ; nor do coils of intestine lie behind the uterus in this section. It will be noticed, therefore, that in the different degrees of distension of the bladder and rectum the uterus is always in the middle line between these viscera, whilst its position varies with its volume. The uterus in this figure lies considerably deeper than in the foregoing ones. The conjugate diameter is 4.2 inches.

FIG. 4. Pelvis of a female of middle age; multipara ; normal. Pirogoff, iii, A, 22, fig. 1. 1. Uterus. 2. Bladder. 3. Rectum. 4. Symphysis.

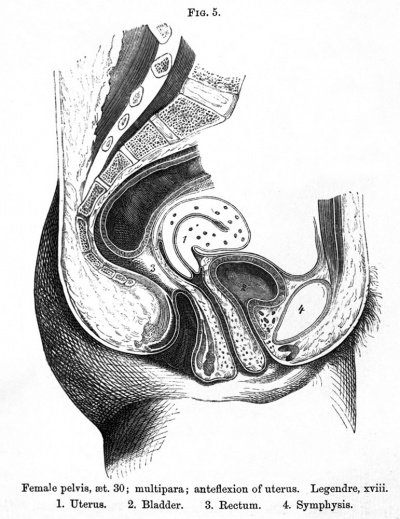

FIG. 5. Female pelvis, set. 30; multipara; anteflexion of uterus. Legendre, xviii. 1. Uterus. 2. Bladder. 3. Rectum. 4. Symphysis.

Fig. 5 (from Legendre), from a section of a frozen body, made after the removal of the viscera, shows well-marked anteflexion of the uterus.

The angle between the body and neck of the uterus impinges upon the rectum. The walls of the uterus appear throughout of uniform thickness, and the rectum and bladder are but slightly encroached upon.

The bladder may be so compressed in the middle line that it assumes an hour-glass form, one portion of it still retaining the urine after the other has been emptied by the catheter. In such conditions the catheter would have to be passed into the further cavity, so that all the urine might be drawn off.

The anterior lip of the os is continued into the anterior wall of the vagina without a clearly defined border, whilst the hinder is strongly prominent and has a length of one inch. The cavity of the vagina contains the canal of the cervix. The vagina itself is 3 inches in length, whilst that in fig. 4 was only 1-5 inch, and the long extended one in fig. 2, 2.8 inches. In like manner the distance of the peritoneum on the posterior wall of the vagina from the perineum is increased, being 3.24 inches ; in fig. 1 it is 2.08 inches. The conjugate diameter is large, being 4.28 inches. The ante-flexed position of the uterus is shown by Schultze to be the normal one in young persons when the bladder is empty. The uterus would, following the contracting bladder, lie upon it, and from traction exercised by the utero-vesical ligament of Courty extend the base of the bladder backwards (cf. Volkmann,'Sammlung Klinisches Yortrage,' No. 50). There is no question that during the variations of the forms of the rectum and bladder, according to the amount of their contents, a space remains in the pelvis near the uterus, which must either be temporarily filled with small intestine, or render necessary a larger amount of variability in the shape of the uterus itself. If we exclude with Claudius and Hennig the possibility of a filling-up of Douglas's pouch by the small intestine, in the case of the bladder and rectum being empty, the difficulty of representing the topography of the uterus would be enormous, as is evident to every experienced anatomist. We have the choice only, either with Henke to show the uterus set up at a fixed angle with the vagina surrounded by small intestine, or with Schultze to represent it bent over on the bladder. However important it may be to determine these relations accurately, I do not think that it can be done at present ; in any case I should not follow Schultze's statement completely. The extension of the base of the bladder does not appear to me in Schultze's plate to be correct, still less so does the assumption of a forcing of the same by means of a ligament, as Courty describes. The lax cellular tissue which lies between the uterus and the base of the bladder, and in which a large number of thin-walled veins run, cannot be regarded as a ligament in the usual sense of the word, and is not shown as such in my plates. It would be necessary to obtain a series of bodies of young females in order to study the variations of the position of the uterus in well-hardened preparations.

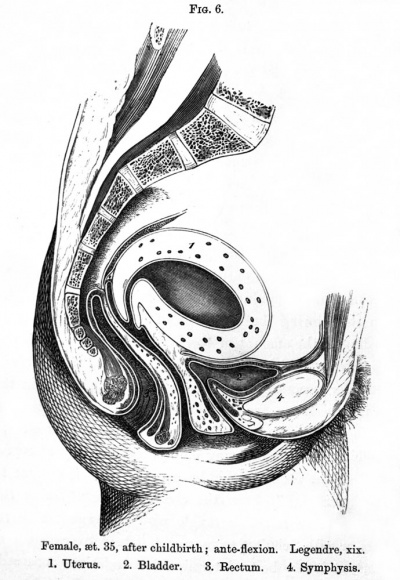

Fig. 6. Female, set. 35, after childbirth ; ante-flexion. Legendre, xix. 1. Uterus. 2. Bladder. 3. Rectum. 4. Symphysis.

The woman (fig. 6) died immediately after childbirth ; the anteflexion also was recent, brought on by the weight of the heavy body of the uterus, which had a capacity of about two fluid ounces.

The flexion is so considerable that the body and neck of the uterus are almost at a right angle with each other, and on the anterior wall a distinct fold is formed. The posterior wall of the uterus rests on the rectum, and presses on its lumen, &c. The vagina is distended and measures 3.6 inches. The distance of the peritoneum on the posterior wall of the uterus from the perineum is 3.8 inches. These figures consequently considerably exceed those in the preceding case.

The position of the fundus with regard to the firmly-compressed bladder is to be remarked here, so also the position of that portion of the peritoneum which lies between the uterus and bladder on the anterior wall of the vagina. In the normal condition of the uterus its end lies nearest the peritoneum, whereas it is here in the middle. It is further to be noticed that the strong attachment of the posterior portion of the base of the bladder with the neck of the uterus (which as already mentioned is admitted by Courty) is not present in this preparation, otherwise the bladder and urethra lying close down on the uterus would be dragged upwards. Nevertheless, the lax cellular tissue and fascia between these viscera is not so capable of distension that variations in the position of the uterus could continue without any influence on the bladder. We notice here that a large piece of the posterior portion of the base of the bladder has been drawn upwards, a condition which would interfere with the action of the vesical sphincter, and consequently cause an incontinence of urine. The conjugate diameter is very large, 5 inches, and exceeds that in PI. II.

The ante-flexed position of the uterus is very well represented by Legendre, as is also to be found in Pirogoff's ' Atlas,' and in Riidinger's ' Topogr. Chirurgische Anatomie,' i, II Abtheilung, taf. ii.

The female from which this plate was made died shortly after instrumental labour, and was soon given over to Riidinger, who froze it and obtained a good section. The thick- walled uterus had dragged the small intestine upwards and lay with its fundus high above the symphysis. Here also the base of the bladder had not followed the traction exerted by the ante-flexed uterus, so that the statement of Courty is not borne out in this case.

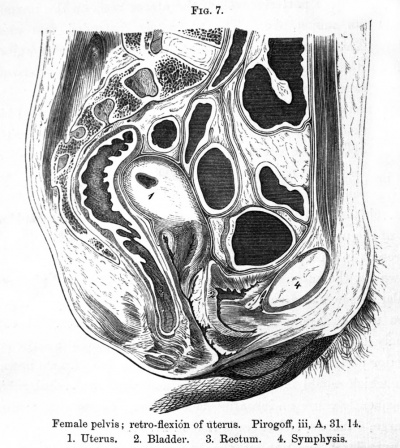

FIG. 7. Female pelvis; retro-flexion of uterus. Pirogoff, iii, A, 31. 14. 1. Uterus. 2. Bladder. 3. Rectum. 4. Symphysis.

Fig. 7 shows a retro-flexion of the uterus. The thick hyperaemic uterus, which has been opened at one spot only (1), contains masses of coagulated blood, and shows retro-flexion as well as a lateral deviation. The body of the uterus lay more in the left half of the pelvis, and the neck, which was divided throughout its length, kept its original position. Such a condition of the uterus would cause a pressure on the rectum which would be increased to complete compression were the retro-flexion more extended.

Therefore, if the retro-flexion be very considerable a stoppage of faeces may be expected, but ante-flexion, as the preceding figure shows, is able to produce a similar result. The conjugate diameter was 4.4 inches.

If, with a view of forming any conclusions, the figures here given be compared, it is at once noticed that the statement of Claudius (" Bericht liber die Naturforscherversammlung zu Giessen," 1865, ' Zeitschrift fur Eationelle Medizin,' iii Reihe, 23 B., p. 244), according to which the normal uterus is not so movable and not so enclosed on all sides by coils of small intestine as is generally represented, is quite borne out. The uterus lies so much more between the bladder and the rectum, that Douglas's pouch contains no small intestine. Corresponding with this is the gravid uterus in PL II, A, B, in closer apposition with the hinder wall of the pelvis. However, as I have mentioned above, I am not able to express myself precisely on this matter.

It would be important to institute further investigations on pregnant bodies to find out whether the sharp bending seen in PL II, A, B, is post mortem or not; at all events, the fact of lying the body on its back cannot alone be the reason of it. If the uterus were ante-verted, and directly after death sank from its own weight into the position of retro-flexion, we must expect that during life there may have been similar variations when a supine position is taken up repeatedly and for a long time at once. On the other hand, I cannot assent to the statement of Claudius, when he affirms that the bladder by its filling and emptying communicates no movement to the uterus. I have already mentioned that one can demonstrate that an influence is exerted by the full and empty bladder upon the site of the uterus on the dead body, also on the living subject the variations of the position of the uterus from micturition can be made out. A cup-like sinking-in of the upper wall is shown, moreover, in the empty bladder only, when the subjects are not very fresh and the urine has been voided immediately before death. The round and empty bladder with its firmly contracted thickened walls (Plate II) shows the normal relaxations of this viscus when it has been emptied by its own power of contraction.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

- Braune Plates (1877): 1. Male - Sagittal body | 2. Female - Sagittal body | 3. Obliquely transverse head | 4. Transverse internal ear | 5. Transverse head | 6. Transverse neck | 7. Transverse neck and shoulders | 8. Transverse level first dorsal vertebra | 9. Transverse thorax level of third dorsal vertebra | 10. Transverse level aortic arch and fourth dorsal vertebra | 11. Transverse level of the bulbus aortae and sixth dorsal vertebra | 12. Transverse level of mitral valve and eighth dorsal vertebra | 13. Transverse level of heart apex and ninth dorsal vertebra | 14. Transverse liver stomach spleen at level of eleventh dorsal vertebra | 15. Transverse pancreas and kidneys at level of L1 vertebra | 16. Transverse through transverse colon at level of intervertebral space between L3 L4 vertebra | 17. Transverse pelvis at level of head of thigh bone | 18. Transverse male pelvis | 19. knee and right foot | 20. Transverse thigh | 21. Transverse left thigh | 22. Transverse lower left thigh and knee | 23. Transverse upper and middle left leg | 24. Transverse lower left leg | 25. Male - Frontal thorax | 26. Elbow-joint hand and third finger | 27. Transverse left arm | 28. Transverse left fore-arm | 29. Sagittal female pregnancy | 30. Sagittal female pregnancy | 31. Sagittal female at term

Reference

Braune W. An atlas of topographical anatomy after plane sections of frozen bodies. (1877) Trans. by Edward Bellamy. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2026, February 27) Embryology Book - An Atlas of Topographical Anatomy 2. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_An_Atlas_of_Topographical_Anatomy_2

- © Dr Mark Hill 2026, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G