Book - An Atlas of Topographical Anatomy 1

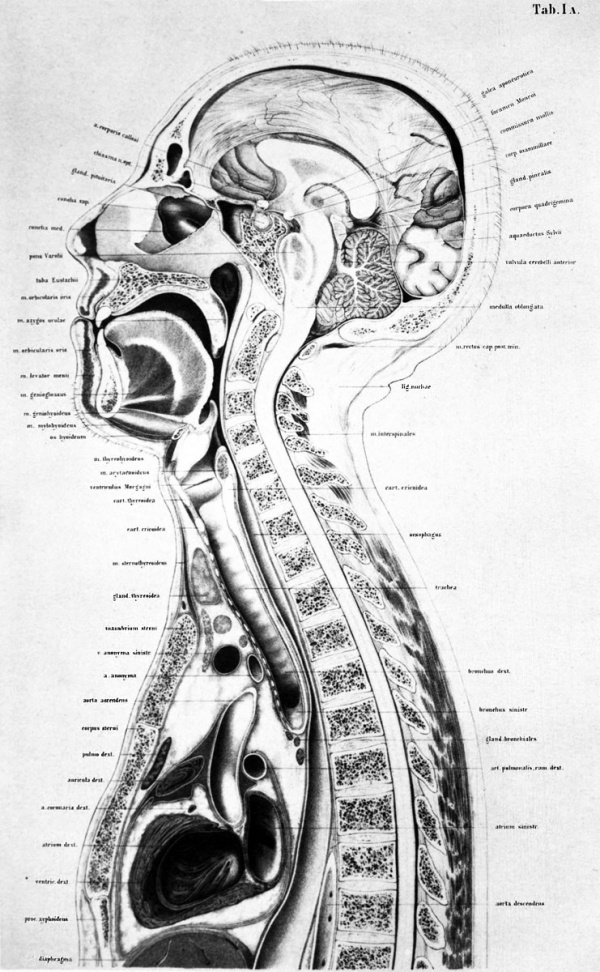

I. Sagittal section of the body of a male

| Embryology - 30 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Braune W. An atlas of topographical anatomy after plane sections of frozen bodies. (1877) Trans. by Edward Bellamy. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

- Plates: 1. Male - Sagittal body | 2. Female - Sagittal body | 3. Obliquely transverse head | 4. Transverse internal ear | 5. Transverse head | 6. Transverse neck | 7. Transverse neck and shoulders | 8. Transverse level first dorsal vertebra | 9. Transverse thorax level of third dorsal vertebra | 10. Transverse level aortic arch and fourth dorsal vertebra | 11. Transverse level of the bulbus aortae and sixth dorsal vertebra | 12. Transverse level of mitral valve and eighth dorsal vertebra | 13. Transverse level of heart apex and ninth dorsal vertebra | 14. Transverse liver stomach spleen at level of eleventh dorsal vertebra | 15. Transverse pancreas and kidneys at level of L1 vertebra | 16. Transverse through transverse colon at level of intervertebral space between L3 L4 vertebra | 17. Transverse pelvis at level of head of thigh bone | 18. Transverse male pelvis | 19. knee and right foot | 20. Transverse thigh | 21. Transverse left thigh | 22. Transverse lower left thigh and knee | 23. Transverse upper and middle left leg | 24. Transverse lower left leg | 25. Male - Frontal thorax | 26. Elbow-joint hand and third finger | 27. Transverse left arm | 28. Transverse left fore-arm | 29. Sagittal female pregnancy | 30. Sagittal female pregnancy | 31. Sagittal female at term

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Sagittal section of the body of a male, set.

THE accompanying plate was taken from the body of a powerful, well-built, perfectly normal man, aged 21, who had hanged himself. The organs exhibited no pathological irregularities. The body, which was brought in unfrozen, was placed on a horizontal board, without any special support for the head, and it was only by laying it down that provision could be made for the limbs lying as symmetrically as possible with regard to the mesial line. In this position the subject lay untouched in the open air, and at a temperature of about 50 F., for fourteen days. At the end of this time the process of freezing was commenced and completed. The mesial line of the body was next accurately marked out anteriorly and posteriorly with a black line, and the section carefully performed by means of a broad, fine-edged saw, much in the same way as two workmen would saw the trunk of a tree. After cleansing the surface, the right half of the body showed that a most successful section had been made. In the brain the fifth ventricle had been traversed ; in the thorax the mediastinum, so that neither of the pleurse was opened ; and in the pelvis the upper third of the urethra. The tracing was then taken from the frozen surface. Where the course of the section had not exactly kept the mesial plane, I improved the preparation subsequently in such places as the nature of the case required. Thus, a thin slice of the cerebellum was removed by means of a razor, and the entire course of the aquseductus Sylvii exposed down to the fourth ventricle, with the penile portion of the urethra and the anus where not opened in the middle line. The plane of the section passed close against the contracted anus, which was opened after the body had thawed ; this accounts for the apparent size of this passage. In sections which pass through the anus in the frozen condition of the body the anterior wall lies nearer to the posterior, not, however, so close that complete apposition is permitted.

It is also to be observed that the details in these plates were worked out from fresh preparations, in order to produce as useful a result as possible; due notice will be taken of these details in the proper places.

With regard to the structures entering into the formation of the skeleton as seen in the section, the vertebral column holds the chief place. The section has been so directed that it passes almost through the middle line of the bodies of the vertebra; and that the arches, on the other hand, as is clear in the dorsal region, are divided somewhat to the right of the middle line.

An examination of the individual portions of the vertebra shows the spinal column to be quite normal. No deformity at all was to be found in the bodies of the vertebra (as is so frequently the case in aged individuals), but, on the other hand, a great amount of mobility in the parts was met with, characteristic of a young and actively built person. The sacrum was devoid of any irregularity, and had a perfect and uniform curve. That only two portions of the coccyx are to be seen in the plate is owing to a variation which this part of the skeleton presents, and is not remarkable.

On examination of the vertebral column in general, its considerable amount of curvature is first of all worthy of notice.

One would clearly expect that in the horizontal position a flatter curve would be met with, as the spine, when examined in preparations after the removal of the thoracic wall and viscera, shows a much flatter arc in the two halves of the body.

Parow, however, has proved (Yirchow's ' Archiv/ Bd. xxxi, p. 108, &c.) that the removal of the viscera of the thorax causes a great increase in the flattening of the spinal column. One needs only to compare the method which was stated by him after the measurement of an isolated vertebra, and is figured a a 0, PI. Y, fig. 4, with that given by E. "Weber ('Mechanik der menschlichen G-ehwerkzeuge ') and with mine, in order to see at once the great difference.

If the plate before us be compared with that which Pirogoff (' Anatome Topographica,' 1859, fasc. I, A, Tab. 10, 11), made from a body which was also frozen in the horizontal position, and then sectioned, it will be found that the curvatures are nearly exactly the same. Both differ, however, in this respect from Weber's, as they do not show so considerable a concavity in the dorsal region. As Parow found by his observations that the contents of the abdominal cavity, although not on so high a level as those of the thorax, influenced the position of the vertebra, we must look for the cause of this slight difference in Weber's preparation in the previous eventration. Although Weber's proposition for the establishment of the shape of the vertebral column, with its ligaments and discs, is excellent, still it is not thoroughly applicable to all vertebral columns in connection with the soft parts, and must, therefore, be modified according to circumstances.

It would seem now worth while, in the vertebral column before us, to be able to determine what this variation would be in the upright position of the individual, but, unfortunately, the means of doing so are impossible.

If any series of representations of the body frozen in the upright position were given, no advantage would be obtained. It is evident that it is impracticable to keep a body so balanced, and in such equilibrium, as the muscles are capable of doing during life. The trunk always hangs over to one side to such an extent that the spine partly loses its original curvature and takes a semiflexure. It is therefore not to be wondered at that the figure which Pirogoff (a a 0, Tab. 12) gives, taken from a subject frozen in the upright position, exhibits curves having flatter arcs than it would have had if the drawings had been taken from one frozen in the horizontal position. We should consequently fall into a great error if we conclude on the ground of Pirogoff 's plate that in the living individual, whilst in the upright position, the spine has a lesser curvature than when lying down. Parow, indeed, by the help of an instrument (Coordinatenmesser), carried out a number of observations with a view of determining the position of the spinous processes, and so estimated the curvature of the spinal column on the living body.

But valuable as these observations are in an individual case, and however carefully followed out, with a view of showing that each variation of the attitude and balance of the trunk exercises an influence on the position of the vertebrae, it appears to me from the great variation in the forms of the spinous processes, that no absolute rule for the position of the bodies of the vertebra can be adduced, more especially as the exact definition of the promontory still renders special measurements necessary. Therefore I have, apart from this consideration, by comparing Parow's curves with my own plates, estimated the alteration which the spinal column presents in the upright position. An exact determination of the line of gravity of the spinal column in my preparation must likewise be given up. It is not possible to estimate with certainty how this line passes through the individual sections of the vertebrae ; and such definitions can only be undertaken on the living body. If the figure be placed in the upright position, and the head be considered as held forwards, as is the case when balanced on the spine, the excessive convexity in the cervical region becomes somewhat flattened, and a plumb-line hanging from the occipito-atloid articulation would cut approximately the vertebral segments, as the brothers "Weber have shown. It passes downwards close behind the promontory and through the line of junction' of the heads of the thigh bones, and indeed Parow has by his measurements fallen back on this proposition of Weber's.

Also it is shown by examining the inclination of the pelvis both in my plate and in the one given by Pirogoff, that this is much more considerable than Meyer gives it, and presents nearly the same angle that Weber has determined by his measurements. The line joining the upper border of the symphysis pubis with the promontory of the sacrum makes an angle of 60 with the horizon.

The ligamentous structures belonging to the vertebrae are represented in the plate as accurately as possible. The separate portions also, such as those of the compound ligamentous apparatus of the articulations of the cranium, and those passing down on the anterior and posterior surface of the bodies of the vertebrae, could not be shown in any detail in such a section.

However, at the odontoid process of the second cervical vertebra the transverse ligament, with its articulation on the anterior cartilaginous surface opposite the joint fissure between the atlas and odontoid process, is clearly seen, as also are the sharply defined elastic ligamenta subflava. The posterior occipito-atloid ligaments which close in the spinal canal between the occiput, atlas, and axis, have not the elastic quality of the ligamenta flava ; they are but slightly distinct from the overlying cellular tissue, and therefore not particularly prominent in the drawing. The section has passed so exactly in the mesial line, that in the neck no muscles are seen except the inter spinales, and one in the lumbar region showing through its sheath. In the dorsal region, on the other hand, where the section had passed somewhat to the right side, the tendon-like structure of the multifidus and semispinalis muscles appear. The space between the spinous processes appears in other places filled up with connective tissue, which belongs to the interspinous and supraspinous ligaments derived from the ligamentum nuchse above. At the inferior end of the spine is seen the posterior sacro-coccygeal ligament, which closes in the end of the spinal canal, and attaches itself to the two portions of the coccyx here shown. The intervertebral discs are represented exactly as they appeared, and their fibrous structure and pulpy centre are clearly shown. It appears that in the most movable parts, such as the cervical and lumbar regions, the discs have an unequable thickness before and behind, whilst those in the dorsal region are of an even thickness. The bodies of the vertebrae in the region of the thorax are of different depths, anteriorly and posteriorly, and consequently influence the curvature of the spine ; and it is shown in the region of the neck and loins, which are the most movable, that the intervertebral discs are essentially stronger anteriorly than posteriorly, though the sides of their respective vertebrae are equally deep.

There is nothing peculiar to remark of the sternum and skull ; they are sufficiently characterised throughout. The spongy portion is accurately shown in each individual bone of the preparation. Especial care was required to bring each portion of the brain clearly under notice. Sections through fresh brains were used in order that the drawing-in of the parts within the dense contours should be made clear and correct.

Beneath the corpus callosum a good view is obtained of the fornix. It is seen as it passes forward and downward from the splenium, and stopping at the corpus mammillare which lies at the base of the skull. In front of this last lies the infundibulum, which leads to the pituitary body in the sella turcica. Still further forward is a section of the optic chiasma. At the extremity of the fornix is the anterior white commissure. Behind the fornix is the black cleft representing the foramen of Munro, and the inner grey lamina of the optic thalamus with the grey commissure. From the upper white lamina of this some fibres are to be seen passing to the pineal gland, which is in relation inferiorly with the posterior white commissure and the corpora quadrigemina. Beneath the corpora quadrigemina is the aquseductus Sylvii uniting the third and fourth ventricles ; the anterior half of this is covered by the corpora quadrigemina, the posterior half being provided with grey convolutions above from the valve of Vieussens. The floor of the fourth ventricle is formed of grey matter, which is shown to be as a continuation of the grey nucleus of the medulla. This becomes clear from the departure of the posterior fibres of the medulla to the cerebellum.

In the pons Varolii a white band is well seen, the penetrating fibres of the pyramid, whilst those of the olivary body go through between the pons and cerebellum. Behind the pons is seen a portion of the nucleus of the olivary body cut through. Between the several portions of the brain which are not directly in apposition, the sites of the great subarachnoid spaces are seen. One, for instance, between the anterior (here upper) border of the pons and the corpus mammillare, and a second between the cerebellum, the medulla, and the commencement of the spinal cord; a third between the posterior part of the corpus callosum and the cerebellum. The investing arachnoid, which, springing across from one portion of the brain to another, so forms this space, cannot be reproduced in the plate on account of its excessive fineness. Excepting the artery of the corpus callosum, which passes upwards over the genu, all the vessels depicted are veins.

The superior longitudinal sinus is laid open for almost its entire extent. The inferior longitudinal sinus on the lower border of the falx is only to be distinguished by the blood seen through its walls. Beneath the splenium the vena Galeni magna passes upwards in order to empty into the straight sinus, of which only a small portion is met with at its junction with the lateral, whilst the thyroid plexuses of the third and fourth ventricles are very evident and clearly represented in the plate. The dura mater, which in the cavity of the skull lies close down upon the bone and on the foramen magnum, and is connected with the external periosteum, leaves the bony walls in the spinal canal and approaches the cord. At the commencement of the cauda equina at the lumbar vertebra the cord can (in the plate) be no longer distinguished from the dura mater.

It will be observed that a portion of the septum narium has been removed. This has resulted from its deflection towards the left side. It was not caused by a polypus. I amplified the defect somewhat in order to bring the relation of the mucous membrane to the septum narium and the two upper turbinated bones clearly into view. Behind the septum is seen the inferior opening of the Eustachian tube. It follows from the relation of the parts, that instruments which are introduced into the tube must be passed along the floor of the nares in order to preserve the necessary direction. The plate shows that an examination of the opening of the Eustachian tube by means of the laryngoscope, would be materially facilitated by drawing the velum forward and upward. The relation of the uvula to the glands and muscular tissue is evident. The thickness of the velum must be borne in mind in. the operation of staphyloraphy. One is inclined to underrate its thickness, and thus to experience difficulty in freshening the edges of the cleft.

Mouth. Before the freezing of the subject the contents of the stomach had ascended into the oesophagus, and partly filled up the cavity of the mouth. After removal of the frozen mass its tube could be represented in the plate.

It can be seen also in the present preparation that the tongue is formed like a muscular pestle, which can thrust hither and thither the contents of the cavity of the mouth. The relation between the tongue, hyoid bone, and larynx is clearly shown. If the surgeon desires to reach the larynx easily, he only requires to draw the tongue out of the open mouth, and can then move the epiglottis and with it the larynx upwards and forwards. The parts of the hyoid bone and the neighbouring organs, which are here shown, are similar to those represented in Pirogoff's plate, and as it was not taken from a person who had died by hanging, they may be regarded as normal.

The larynx is evenly divided in the mesial plane, and offers no peculiarities for consideration. The sections of the cricoid and thyroid cartilages, and the ventricle of Morgagni between them, are shown, and, on account of the apposition of the vocal cords, the ventricle appears only as a cleft. The muscles to be noticed in this section are, on the posterior wall of the larynx, the transverse section of the arytenoideus, anteriorly, between the cricoid and thyroid cartilages, some fibres of the crico-thyroid lying close in the mesial line, and above a portion of the thyro-hyoid.

The ligaments shown are the glosso-epiglottic, the middle thyro-hyoid, and further down the middle crico-thyroid.

The section of the neck is so closely in the mesial plane that no vessels are seen, except a vein above the manubrium sterni, a communicating branch uniting two subcutaneous veins of ,the neck. It lies enclosed between two laminaD of fascia, which arise from the splitting of the anterior lamina of the cervical fascia. Behind this lies the cut edge of the sterno-thyroid muscle. Between this muscle and the trachea is the section of the middle portion of the thyroid body which is perfectly normal in its relations. The plate shows the direction taken by the knife in tracheotomy, and the importance of keeping the incision exactly in the middle line of the neck.

The absence of arteries in the middle line, as is almost uniformly the case, shows that there is less apprehension of danger in the middle line from haemorrhage than laterally. The thyroidea ima artery is the only one which would be met with in such a plane, and this, according to Neubauer, is found in one in every ten bodies. Since this vessel takes its origin in almost all cases from the innomminate its distribution must be looked for somewhat towards the right of the middle line. As the trachea lies further distant from the surface of the body as it descends, the operation of tracheotomy is easier of performance the nearer the surgeon approaches the larynx, consequently, unless there are contra-indications, it should be performed above the thyroid body. It must be recollected that this gland should be drawn upwards by a blunt instrument in order to freely expose the upper rings of the trachea, a proceeding unattended with difficulty owing to the mobility of the organ. Should the operation be performed below the thyroid body there is a considerable depth of tissue to get through before reaching the trachea, and, moreover, great attention must be paid to the position of the vessels of the neck. The position of these trunks is not so constant that any general rule for their distance from the upper edge of the sternum can be given.

The trachea, which in this preparation divides into the two bronchi opposite the fourth dorsal vertebra, has tolerably the same relations, as shown by Luschka (' Brustorgane,' Tubingen, 1857). It appears, however, from sections on other bodies that there is no constant point of division, and different authors make different statements on this matter. Henle (' Anatomic, ' 1866, Bd. ii, p. 26 A), describes it as opposite the fifth dorsal vertebra. Pirogoff in his plate (Fasciculus I A, tab. 14), gives it as high as the third.

Thorax. The slight depth of the thorax is striking, and yet one can convince oneself, both from measurements on the living body and also from Pirogoff's plates, that there is in this case no abnormality. The mediastinum was so exactly divided by the section that neither pleural sac was opened ; whilst of the lungs, nothing is seen but a small strip of the right, which, covered by pleura, is shown behind the body of the sternum. In Pirogoff's plate (Fasc. I A, tab. 10, 44), no lung is to be seen, by reason of the considerable breadth of the mediastinum. The heart was so divided that only a flat piece of the arch of the aorta remained in the right half of the body, whilst the root of the pulmonary artery was removed with the left side, its right branch being cut through The superior and inferior venge cavae are not seen at all, they lie deeply, and empty themselves above and below into the right auricle, so that their point of entrance cannot be clearly made out. If, in the plate, a line be drawn from the anterior border of the septum auriculorum outwards and downwards, the situation of these deeply lying vessels will be indicated. The large cavity in front of and below the aorta belongs to the right auricle, the larger portion of which remained on the right half of the body. Its cavity extends upwards toward the right auricular appendix, of which, as is clear !>v the plate, only a small portton nabbed across to the left half of the body posteriorly towards the vertebrae, and somewhat behind the left auricle. A large portion of the tricuspid valve has been removed in the section.

Only a small portion of the left auricle is left, and this is seen lying ???? it Mini the SpillSlI ColuiMII. Al.O.lt t Wo

thirds of it were removed with the left half of the body. The two openings into it correspond to the entrance of the pulmonary veins. That portion of the auricular septum containing the foramen ovale is removed, and only a small portion of the right ventricle is noticed.

Here the heart was cut obliquely near its upper SHI -I'; ice, and therefore its muscular tissue and fatty layer appear remarkably clearly. There is a considerable

amount of l':i.l. <ii the heart . Tin- muscular structure of the heart and Yahres, however, shows no irregularity. The relation of the pericardium is clearly shown. The accompanying woodcut explains Uio position of Mm In-art, wit h regard to t ho mesial lino as found in the present case, from whence result the rules for its percussion. It will

| M > noliced th.-it tin- relations agl'e exactly with those {.riven ly Luschka (loc. fiit. t tab. iii).

Tin- entire IniHli of tin- (rsopliinnis is not^ distinctly shown liy UKin. 'di. in section, :is in ccrtnin plan-s tin- lulu- diverged ronsiilrrnhly from the

middle lino. In this preparation, however, on account of the contents of

tin- slniuiidi h;i\ in.r i-iMnir.riinird into ii, it \v:is so distcndeil that lliejilano ' ' incl it ihi-oii^l,,,,,! j| s ( . ( ,|,,- S( ..

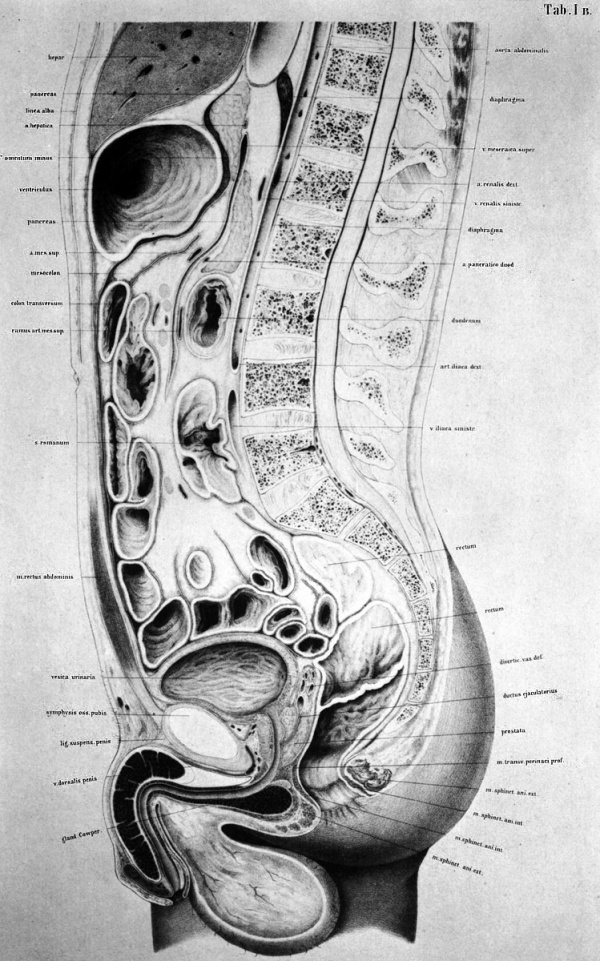

Abdomen. It can be seen from the form of the abdominal walls, that there is no sinking-in of the parietes, but, although the intestines were

moderately di-t.-mled. the short distance of the iinibiliciis 1'roin the luinhar

vortebrno is very remarkable. The depth of the abdomen in the mesial lino is, indeed, very variable, and is generally represented far too great.

But it is to be expressly noticed here that, the condition of parts seen in the present drawing is not precisely the same as in the living body, sinco in the dead subject the lungs are in the position of fullest expiration, and the diaphragm reaches its highest level ; and the relation of the intestines with it, the distribution of the blood, and the arching forward of the abdomen, are somewhat altered. Therefore, with reference to the living body, the distance of the vertebral column from the abdominal walls must be considered as somewhat greater, although not so much so as one is accustomed to suppose. From this relation of the parietes to the vertebrae, the possibility of the ready compression of the abdominal aorta may be inferred. Compression becomes the easier the thinner the individual and the less full the intestines. Further, it is evident that the individual should lie in such a position that the lumbar vertebras be bowed as much forward as possible ; and as the aorta bifurcates on the fourth lumbar vertebra, the pressure should be brought to bear directly on the navel.

Intestines. The position of the intestines in the middle line should be compared repeatedly with other sections on bodies of the same size. It appeared that a similar figure continually obtained, and that, with exception of some of the coils of intestine, the stomach, duodenum, transverse colon, iliac flexure, and rectum, when in an equal state of distension, lay pretty much in the same position. In one case the stomach was found in such an empty and contracted condition that it was at first entirely overlooked, and when it was found the little finger could be scarcely pushed into its cavity. On examining the abdomen it appears (and more so than in other regions) that the change in the volume of individual organs as well as their mobility may be considerable without other parts having essentially to suffer thereby. For fat and cellular tissue so completely surround the viscera that no empty spaces are left, and thus freedom of movement and compression are permitted.

The section of the liver passes through the left lobe near the lobulus Spigelii.

The pancreas is cut through near its head, where the superior mesenteric vein approaches the liver. The other part of it, which is directed from the head of the gland to the middle line along the lower horizontal portion of the duodenum (the so-called lesser pancreas), lies behind the mesenteric vein, so that it looks as if the vein passed through the pancreas itself.

The relations of the peritoneum are represented in the plate as they were met with after the thawing of the preparation ; only, for the sake of clearness, half the fat of the greater bag of the peritoneum has been taken away and the layers thereof shown somewhat diagrammatically.

A vertical section in the middle line is not the most favorable for showing the mutual disposition of the reflexions of the peritoneum ; an oblique one taken outwards from the foramen of Winslow, through the root of the mesentery to the iliac flexure, would much better answer the purpose. Therefore, in the accompanying woodcut I have given a diagrammatic representation, which will at least make clear the relation of the lesser bag to the other portions of the peritoneum. The individual layers of which the transverse meso-colon is composed, are not represented in this drawing as they cannot be prepared in the full-sized body, and their diagrammatic representation would only complicate the drawing.

On the relations of the rectum there is nothing further to add. The distance of the peritoneal sac from the anus, which is here about three inches, is to me noticed, as is also the position of the so-called valves of the rectum. Since the rectum in its ascending portion courses over towards the left half of the body, there is only a flat section of it to be seen ; in this respect my plate differs from those of Henle and Kohlrausch.

The representation of the bladder also differs from that given by the above-mentioned authors, it was, however, accurately drawn from the preparation. The bladder was completely full of frozen urine, and consequently there was no sinking-in of its upper wall, as is represented in several of Pirogoff's plates. I injected the bladder with tallow as soon after death as possible, partly through the urethra and partly through the ureter, both in the vertical and horizontal position, in order to compare the form and situation of that viscus. A section in the mesial plane in each case showed the same conditions as in the plate, and, with reference to the flattening of the upper wall, no essential difference was found whether the body was upright or lying down.

The position of the entrance of the urethra corresponds with Henle's and Kohlrausch's description, though no absolute similarity need be expected. Langer (' Med. Jahrb. Wien.,' 1862, 3 Heft) has shown that many considerable variations obtain as regards this matter. Especial care was expended on that envelope of the bladder which forms the porta vesicae of Retzius, as this is not very clearly shown in Henle and Kohlrausch. It is shown that from the termination of the posterior wall of the sheath of the rectus (the socalled fold of Douglas) two laminae of fascia take their origin, and then pass down close to one another between the rectus and the peritoneum. If the bladder be only moderately distended, as in this case, they however confine a space in front of the peritoneum, which is taken possession of by the bladder as it rises upwards during distension. The anterior lamina passes downwards as a thin covering upon the rectus abdominis and lines the space between the bladder and the symphysis pubis ; the posterior lamina passes across behind the urachus on to the bladder, in order to invest it, and to join the prostatic capsule and pelvic fascia. The internal vesical sphincter is clearly seen in the plate, but, on the other hand, the external sphincter is not completely brought into view. The limits of the prostate gland are clearly defined, also the parts lying in front of the urethra are accurately represented. In most cases the muscular fibres and gland tissue are not exactly made out.

In front of the prostate is the middle pubo-prostatic ligament with the numerous veins which form the plexus venosus of Santorini. Beneath it is some muscular tissue which has not been completely analysed. It was represented as it stood, and, after Henle, is comprehended under the name of deep transverse perineal muscle; it, moreover, corresponds with Muller's so-called constrictor of the membranous urethra. The triangular ligament of the urethra (Colles), which lies on the ligamentum arcuatum, close beneath the symphysis, and is incorporated with the deep transverse perinei, does not appear very clearly defined in this section. The white portions on the anterior border of the above-mentioned muscular mass are to be referred to this. Vertical sections in an antero-posterior direction are not adapted for the demonstration of the pelvic fasciae and muscles j those made across the axis of the body afford better results.

The dorsal vein of the penis and the suspensory ligament are well shown.

The curvature of the urethra differs somewhat from that which Kohlrausch describes as normal, but the condition here represented must also be regarded as such, since it presents no pathological irregularities nor are there any in neighbouring organs. It must be therefore assumed, as follows from the plate of Pirogoff and Jarjarvay, that this urethral curvature which offers in the normal condition frequent variations can only be generally denned. Moreover, the ease with which instruments can be introduced into the bladder merely by their own weight proves that it is less a question of giving the catheter a definite curvature, than of knowing of the hindrances which might oppose its introduction. The projection in the prostatic portion of the urethra corresponds to the prostatic sinus near the colliculus seminalis, which lies in the section with the ejaculatory duct.

The relations and structure of the glans and corpus cavernosum are well shown, so also is the fossa navicularis. The other dilatations and contractions of the urethra which are regular in the normal body cannot be defined. In order to obtain a clear idea of these, casts must be made from soft specimens as Langer has done, as sections of hard preparations are not of much value. The position of Cowper's glands, which lie so deeply below the urethral muscles, will explain why the inflammation and enlargement, which are frequently found on section to have affected them, are so little regarded during life ; a considerable amount of swelling must occur in order to afford any perceptible tumour.

If the plate be examined with regard to perineal operations, such as lithotomy, one is astonished at the narrowness of the space between the upper portion of the urethra and the rectum. It must be remarked, however, that in the present instance it is peculiarly exaggerated, as the rectum was full of faeces.

The importance of the rule is evident that before the operation of lithotomy be undertaken the rectum be cleared of all faecal matter, in order that it be out of the reach of the knife. That the space is thereby substantially enlarged is manifest from Kohlrausch's plate, which is drawn from a greatly distended rectum.

It is further seen from the relations before us, that it is quite practicable to preserve the capsule of the prostate. By dilating the membranous and prostatic portions of the urethra more room is obtained for entering the bladder, as well as for the removal of large calculi. By the preservation of the posterior part of the prostate with its capsule, dangerous urinary infiltration is obviated. With regard to the high operation of lithotomy above the symphysis there is nothing to remark. The plate also shows that the bladder must be fully distended in order that that part of it which is not covered by peritoneum may be raised sufficiently above the level of the pubic symphysis.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

- Braune Plates (1877): 1. Male - Sagittal body | 2. Female - Sagittal body | 3. Obliquely transverse head | 4. Transverse internal ear | 5. Transverse head | 6. Transverse neck | 7. Transverse neck and shoulders | 8. Transverse level first dorsal vertebra | 9. Transverse thorax level of third dorsal vertebra | 10. Transverse level aortic arch and fourth dorsal vertebra | 11. Transverse level of the bulbus aortae and sixth dorsal vertebra | 12. Transverse level of mitral valve and eighth dorsal vertebra | 13. Transverse level of heart apex and ninth dorsal vertebra | 14. Transverse liver stomach spleen at level of eleventh dorsal vertebra | 15. Transverse pancreas and kidneys at level of L1 vertebra | 16. Transverse through transverse colon at level of intervertebral space between L3 L4 vertebra | 17. Transverse pelvis at level of head of thigh bone | 18. Transverse male pelvis | 19. knee and right foot | 20. Transverse thigh | 21. Transverse left thigh | 22. Transverse lower left thigh and knee | 23. Transverse upper and middle left leg | 24. Transverse lower left leg | 25. Male - Frontal thorax | 26. Elbow-joint hand and third finger | 27. Transverse left arm | 28. Transverse left fore-arm | 29. Sagittal female pregnancy | 30. Sagittal female pregnancy | 31. Sagittal female at term

Reference

Braune W. An atlas of topographical anatomy after plane sections of frozen bodies. (1877) Trans. by Edward Bellamy. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 30) Embryology Book - An Atlas of Topographical Anatomy 1. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_An_Atlas_of_Topographical_Anatomy_1

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G