Paper - The Sexual Cycle in the Human Female as revealed by Vaginal Smears: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 265: | Line 265: | ||

This is in accord with Corner’s and Allen’s views. He also made observations on the cellular changes during gestation. He noticed the presence of the cells of Papanicolaou (navicular). He also found erythrocytes in the pregnancy smear for about 23 days, beginning at the twenty-sixth day since the onset of last menstruation (or 14; to 17 days after fertile | This is in accord with Corner’s and Allen’s views. He also made observations on the cellular changes during gestation. He noticed the presence of the cells of Papanicolaou (navicular). He also found erythrocytes in the pregnancy smear for about 23 days, beginning at the twenty-sixth day since the onset of last menstruation (or 14; to 17 days after fertile | ||

Revision as of 12:12, 8 September 2015

| Embryology - 5 May 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Papanicolaou GN. The Sexual Cycle in the Human Female as revealed by Vaginal Smears. Am J Anat. 1933;52: 519–637.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

| Online Editor |

|---|

| These are currently some of the plates from the historic paper by George Papanicolaou (1883 – 1962) the pathologist who developed the diagnostic "Pap smear" test named after him. Originally a Greek clinician (Georgios Nikolaou Papanikolaou) he travelled throughout Europe before becoming in 1913 an American researcher. His first studies were in other species (Guinea-Pig) before extending the studies onto humans. This paper described the appearance of normal cell smears during the different stages of the menstrual cycle. The true value of the "Pap smear" test was the identification of abnormal cells associated with cytopathology of cancer of the cervix.

The original black and white photomicrographs were hand-coloured by the author to match his microscopic observations. |

The Sexual Cycle In The Human Female As Revealed By Vaginal Smears

George N. Papanicolaou

Department of Anatomy, Cornell University Medical College, and Woman’s Hospital, New York City

- This work has been aided by the Committee for Research on Sex Problems of the National Research Council, and by the National Committee on Maternal Health.

Three Figures and Ten Plates (Eighty-One Figures)

I. Introduction

The study of the female sexual functions in mammals has been greatly stimulated and advanced in recent years by the application of the vaginal smear method. This method, as originally applied to the guinea pig by Stockard and Papanicolaou in 1917, consists in the microscopic examination of smears prepared at frequent intervals from the fluid content of the vagina. The vaginal fluid usually has a mucous consistency and contains a variety of desquamated cells, as well as leucocytes, lymphocytes, often erythrocytes, and a large number of bacteria. As the relative number and the distribution of these elements change periodically, smears prepared from such fluid show modifications in their composition and structure. The successive alternation of periods of sexual activity and inactivity, which characterizes the mammals, imparts to the vaginal fluid a rhythmical sequence of typical cellular stages which can be easily recognized.

These cyclic changes affect the entire genital tract, and, consequently, every change in the vaginal fluid is strictly correlated With corresponding changes in the other organs of

the female genital system, particularly the uterus and the ovaries. The time of ovulation may be accurately detected by this method in living mammals, while, before its application, no such information could be obtained without an operation or the sacrifice of an animal.

In the guinea pig, which is polyoestrous, the sexual cycles

return periodically throughout the year every 15 to 16 days

(15.73 in average). The longest part of each sexual cycle,

i.e., about 12 days, is occupied by a period of relative inactivity or rest, which is called ‘clioestrus.’ During this time

the vaginal smear, as described by Stockard and Papanicolaou ( ’l7), consists chiefly of leucocytes and a varying num-

ber of atypical squamous cells. The period of increased

sexual activity lasts 3 to 4 days and is characterized by a

succession of stages, which have been designated as stages

I, II, III, IV. During stage I the leucocytes almost disappear

from the smear, the secretion of mucus becomes more abundant, and the cells which dominate the smear are of a squamous type with very small pyknotic nuclei which are at times

fragmented. At the end of stage I there is an intermediate

period, characterized by the prevalence of ‘elongate, cornified

cells Without nuclei.’ Stage II also shows a scarcity of leucocytes and a prevalence of cells which are derived from the

deeper layers of the vaginal epithelial wall, being thus less de-

generated and having a larger nucleus and a more compact

form. Stage III is characterized by the reappearance of

myriads of leucocytes and by cells mainly of the II and III

type. The III cells are as a rule modified type II cells, the

bodies of which had been penetrated by the invading leucocytes. Stage IV is practically the same as stage III, with the

difference that erythrocytes are also present in the smear as

the result of slight bleedings.

These four smear stages are of short duration, succeeding one another rapidly and are strictly coordinated with corresponding stages of the uterine and ovarian cycles. During

stage I the ovary contains large ripening follicles and regressing corpora lutea. The uterus is congested and hypertrophied and its epithelial lining consists of high cuboidal or columnar cells. During the intermediate or cornified stage the follicles as well as the uterus reach their highest development. The onset of the catabolic processes, i.e., the bursting

of the ripe follicles and the denudation of the uterine mucosa,

is associated with the appearance of vaginal stages II and III.

Ovulation in the guinea pig is thus characterized by definite

vaginal changes and occurs at about the time of the sloughing

off of the uterine mucosa. Comparable conditions have been

found to exist in other rodents, such as the rat and the mouse.

Long and Evans (’22), in their monograph on the oestrous

cycle in the rat, described definite relations between the vaginal cycle, as revealed by vaginal smears, and the uterine and

ovarian cycles. The rat has normally a very short sexual

periodicity of about 5 days’ duration. Long and Evans recognized five smear stages: Stage 1: Leucocytes disappear;

great numbers of small round nucleated epithelial cells of

strikingly uniform appearance and size; duration 12 hours.

Stage 2, or ‘cornified cell stage’: leucocytes still absent;

appearance of cornified cells. Stage 3, or ‘late cornified cell

stage’: leucocytes absent; rich in cornified cells, forming

large cheesy masses; duration of stages 2 and 3 about 30

hours. Stage 4, or ‘leucocytic—cornified cell stage’: reappearance of leucocytes; gradual disappearance of the cornified

cells and appearance of epithelial cells; duration 6 hours.

Stage 5 corresponds to the dioestrus, which is of an approximate duration of 3 days and is characterized by the presence

of leucocytes and atypical epithelial cells in the vaginal smear.

The cornification of the vagina is much more pronounced

in the rat than in the guinea pig and this accounts for some

of the smear differences between these two animals. In the

rat the cornification extends over two well-defined stages, the

second and third of Long and Evans, whereas in the guinea

pig it is usually overlapped by the I and II to the III stages;

on this account, it had been originally described by Stockard

and Papanicolaou as an intermediate period. In the rat the

uterine growth is completed during the first and second

stages. The catabolic processes in the uterus begin during

the cornified cell stages, and the ovulation occurs during the last hours of this same period. The uterine epithelium is

vacuolized and degenerated, but an actual denudation, as in

the guinea pig, does not occur. The various phases of the

sexual cycle in the rat proceed in rapid succession, but their

coordination is maintained.

The corresponding vaginal smear stages in the guinea pig and the rat could be illustrated as follows:

| Vaginal Smear Comparison Table | |

|---|---|

| Guinea pig | Rat (Long and Evans) |

| I. Superficial squamous cells with pyknotic nuclei; progressive leucopenia. | 1. Small round nucleated cells; disappearance of leucocytes. |

Intermediate (cornification) period

|

Cornification period

|

| II, III, IV. Appearance of deep layer cells; reappearance and great exodus of leucocytes; gradual disappearance of cornifiecl cells; sometimes erythrocytes present. | 4. Leucocytic-cornified cell stage; reappearance of leucocytes; gradual disappearance of the cornified cells. |

| V. Dioestrus: Leucocytes and atypical atypical vaginal cells. | 5. Dioestrus: Leucocytes and vaginal cclls. |

| |

This comparison indicates that the succession of stages is similar in both animals. Ovulation occurs at practically the same moment in relation to the above stages, i.e., at the end of the intermediate period in the guinea pig and during the last hours of the cornification period (second and third) in the rat.

In the mouse, Allen (’22) has also recognized five stages, the entire sexual cycle averaging about 4% days.

Selle (’22) has reclassified the vaginal smears of the guinea pig after a detailed study of the changes in the vaginal epithelium. He has recognized a separate ‘cornified cell stage’ similar to the same stage in the rat. Such a stage may be actually present in a large number ‘of cases, but, as a rule, it is indistinct and overlaps both the preceding and the following stages. This cornified cell stage of Selle corresponds to the ‘intermediate period’ of Stockard and Papanicolaou, and not to the stage 2 as given in Selle’s table. His stage 3 corresponds to the intermediate +II, whereas his stage 4 is equivalent to the stages III and IV of Stockard and Papanicolaou.

Murphey (’22) and Frei and Metzger (’26) have recognized four stages in the oestrous cycle in the cow with the vaginal smear method. Hartman (’23), in his study of the oestrous cycle in the opossum, also recognized four stages corresponding to the ones described in the rodents.

In 1924, McKenzie and Zupp, and in 1926, Wilson studied vaginal smears in swine. They found periodic variations in the cellular and leucocytic make-up of the smears, indicative of a cyclic rhythm.

A further step was made by Corner’s (’23) application of

this method to the Primates. His observations on Macacus

rhesus, though not entirely in line with the smear findings

in the rodents, yet revealed a rhythm in the vaginal reactions.

The average length of cycle in the Macacus, when the regular

cycles are considered, is about 27 days, which is almost the

same as in the human. During menstruation, which lasted

4 to 6 days, the vaginal smear contained erythrocytes, epithelial cells, and leucocytes. In the first half of the intermenstrual interval there were relatively few epithelial cells and

many leucocytes. About the middle of the interval a sharp

drop in leucocytes occurred or even total disappearance.

Leucocytes sometimes reappeared a few days later or were

absent until onset of next menstruation or a few days before.

During the second half of the intermenstrual interval there

was an increased desquamation of epithelial cells. The pre-menstrual smear seemed to be thick and caseous, whereas the

postmenstrual smear was rather thin and scanty.

These observations, though not establishing a definite succession of clear-cut stages, reveal the existence of a rhythm expressed mainly in the periodical increase and decrease in the number of the leucocytes and the epithelial cells. As Corner concludes:

- There is to some degree a cycle of the vaginal secretion in this species. There is hardly enough evidence to warrant a correlation with the much sharper cycle of the rodents; moreover there was seen in the monkeys no massive desquamation of completely cornified epithelial cells and no swarming of leucocytes into the epithelial debris. However, . . . . it seems very likely that the disappearance, or diminution in number of vaginal leucocytes, which usually happened about the tenth to the fifteenth day before the onset of menstruation (in regular cycles of 25 to 30 days) is to be compared with the disappearance of leucocytes from the vagina of rodents at oestrus or shortly before the moment of ovulation.

In a later paper, 1927, in which the presence of menstruation without ovulation in Macacus rhesus was reported, Corner stated that daily vaginal smears, taken from animals with ovulative and non-ovulative cycles, were practically alike. The presence or absence of ovulation could not be ascertained by the examination of vaginal smears.

Allen, in 1927, also studied vaginal smears of the monkey, Macacus rhesus, and found varying numbers of epithelial cells in different stages of cornification. Some of these cells were quite normal, others were flattened and their nuclei were pyknotic. The epithelial elements were present in greatest numbers during the latter half of the second and the whole third week of the cycle. Completely cornified, non-nucleated cells frequently also appeared at these times. Leucocytes were present in greatest numbers before, during, and after menstruation and in least numbers or absent between the tenth and the twentieth to twenty-fourth day of the shorter cycle. During menstruation varying numbers of erythrocytes were present.

Allen’s findings are more or less in line with Corner’s observations, especially in regard to leucocytes. Corner found many leucocytes during and after menstruation and Allen before, during, and after. At about the tenth day both noticed a progressive diminution in the number of the leucocytes. This diminution lasted for a few days or almost up to the onset of next menstruation. In regard to ovulation, they agree that, whenever present, it occurs in the mid-period, between the tenth and the fifteenth days.

The preparation of vaginal smears from the human has been in usein pathology for a long time for the study of various conditions, especially of bacterial infections. However, the application of smears to morphological and physiological studies has been extremely limited up to the last decade.

As early as 1847, Pouchet, in his book on “Ovulation and other related phenomena,” gave a description of human vaginal smears, which is chiefly interesting from a historic standpoint. Though unaided by modern technical methods, he

was able to recognize the existence of a rhythmical reaction

in the vaginal secretion. His work, however, was largely lost

sight of and in no way stimulated attention upon the value

of the vaginal content as an indicator in analyzing the phases

of the sexual cycle. The recent interest and activity in these studies can in no sense be connected with or attributed to this early pioneer effort by Pouchet.

He describes the vaginal mucus as becoming less dense

shortly before menstruation and as acquiring a peculiar odor

(une odeur ‘sui generis’), to which he attributed an exciting

effect upon sex desire. Microscopically, the vaginal fluid

showed fragments of epithelium and lacerated pieces, some

consisting only of the ‘tubercule central’ (he evidently meant

the ‘nucleus’), also large numbers of ‘globules muqueux’ (meaning probably the leucocytes) and some erythrocytes.

During the menstrual phase (‘période d’état’) he records the enormous quantity of erythrocytes, of mucous globules, and of small and transparent epithelial fragments. He believed that ovulation occurs toward the end of the menstrual phase, when the sex desire is most imperative. The menstrual phase is followed by a ‘period of desquamation,’ lasting approximately 10 days. This period is characterized by the detachment of a considerable quantity. of epithelial plates (‘Plaques d ’épithélium ’) .

During the sixth and seventh days after the end of menstruation (eleventh to twelfth day after onset) the vaginal mucus begins to lose its transparency and becomes heavier. Large numbers of epithelial plates are present and the mucous globules become more abundant. At about this time, or on the eighth day after menstruation (thirteenth day since the onset), some women experienced a feeling of heaviness or sharp pains lasting 1 to 2 days. Pouchet attributed these to contractions of the fallopian tubes, and not to the ovulative process, which he thought to occur much earlier.

Between the tenth and fiftenth days after cessation (fifteenth to twentieth day after onset of menstruation) pieces

of uterine decidua (‘flocon membraneux’) were expelled in

a number of cases. Pouchet interpreted this as an abortive

process and believed that a woman could only conceive between the time of menstruation and the spontaneous fall of

this decidua.

In 1921, Lehmann made a study of the diagnostic value of

the human vaginal smear. Interested chiefly from a pathological and diagnostic point of view, he did not attempt to

establish definite morphological and physiological relations

between the changes in the vaginal fluid and the ovarian and

uterine cycles. He recognized, however, the dependence of

certain vaginal conditions, such as secretion of glycogen,

acidity, or bacterial growth on ovarian and uterine functions.

In 1925, I announced in a preliminary report some of the early results of my human vaginal smear studies. I held that there are definite morphological changes in the vaginal fluid by which a diagnosis of certain physiological and pathological conditions is made possible.

Pregnancy, cystic or other degenerative changes of the

ovaries, inflammatory processes, growth, etc., affect the entire

genital tract, including the vagina, in a way which produces

definite and typical changes in the consistency and make-up

of the vaginal smear. The presence or absence of different

types of desquamated cells, as well as the varying form and

number of leucocytes, lymphocytes, erythrocytes and bacteria,

offer a variety of criteria upon which a diagnosis of certain.

conditions may be based.

These observations were mainly on the morphological changes of the various constituents of the smear, and not merely on quantitative estimates of the relative number of

leucocytes or cells.

In the same year, Allen (’25) reported tests on human vaginal smears from gynecological patients in collaboration

with Dr. Q. Newell. He stated that—

- Although they found a decided variation in the number of leucocytes and epithelial cells at different times in the cycle, results were not nearly so clear-cut as in rats, because normally no cornification occurs in the vaginal epithelium of women. Furthermore, the smear test is of greatest value in animals, in which sexual changes are not as clearly marked externally. In the primates menstruation furnishes such a prominent milestone that vaginal smears seem of secondary importance for diagnosis.

A year later, King ( ’26) published her studies on human vaginal smears. She found that “in general the secretion is more scanty during the first few days following menstruation and the cells show less degeneration during the first part of the cycle than in the late intermenstrual and premenstrual phases. The leucocytes are of the polymorph type, although an occasional mononuclear can be seen.” She also found a definite decrease in the number of leucocytes and a relatively high content of epithelial cells in one cycle of case D, on the thirteenth day after one onset and 16 days before the next. A similar condition was seen in the third interval of case F, beginning in the middle of a 22-day cycle.” She considers this fall in leucocytes as being probably comparable to the intermenstrual decrease noticed in some of Corner’s monkeys which may bear a relation to the time of ovulation. She states, however, that there were great irregularities in this respect in other cases.

Two types of secretion described by Lehmann for normal adults may be found, according to her, in the same individual and, in addition, there is a type in which the content in both

leucocytes and epithelial cells is high. She concludes that—

The cellular content of the vaginal secretion of the normal human female is exceedingly variable and is a doubtful index of changes transpiring in the ovary and uterus. The indications of periodic variation are even less evident than those found by Corner for the monkey. Considering the higher degree of specialization, this is the condition which might reasonably be expected.

A Mexican gynecologist, Ramirez[1] published, in 1928, a study of the human vaginal smear cycle. He recognized five provisional types of cells: I) Cells with a large and round nucleus clearly outlined, finely reticulated, and taking a violet-reddish color with Leischmann’s stain; cytoplasm reticulated, pale-blue, with or without inclusions. II) Cells with a large round or oval nucleus having a thick reticulum, granular or semigranular; cytoplasm spongy, bluish, with inclusions and vacuoles. III) Cells with a much smaller nucleus having a thick reticulum or forming granules, irregularly outlined, taking a blue-violet color; cytoplasm condensed, bluish, vacuolated with inclusions. IV) Cells with a small, pyknotic granular or simply structureless nucleus of bluish or wine shade; cytoplasm spongio-granular with abundant inclusions and with or without large vacuoles. V) Anucleate cells and cells with only a trace of a nucleus. The nucleus appears as a mass of granules which seem to be dispersed in the granular cytoplasm. All the granulations, nuclear or cytoplasmic, display the same bluish color.

Ramirez found that during menstruation the prevailing cellular type is: I (49 per cent), II (27 per cent), III (20 percent), IV (4 per cent), and V (0); leucocytes, scarce at first, increase toward the end. During the post menstrual period (2 to 3 days after menstruation) the cell percentages were as follows: I (1 per cent), II (9 per cent), III (24 per cent), IV (60 per cent), V (6 per cent) ; many polynuclear neutrophilic leucocytes. During the early interval (4 to 8 days after menstruation): I (0), II (15 per cent), III (25 per cent), IV (52 per cent), and V (8 per cent). During the interval (8 days after menstruation) : I (0), II (1 per cent), III (42 per cent), IV (45 per cent), and V (12 per cent) ; leucocytes exceptional.

Type V was prevalent in pregnancy, where the cellular percentages were as follows: I (0), II (0), III (18 per cent), IV (12 per cent), and V (70 per cent). The aspect of the smear was entirely different during pregnancy and the cells showed a tendency to form large groups or laminae. Ramirez arrived at the same conclusion that I had in 1925, that pregnancy may be diagnosed through the cytological characteristics of vaginal smears. His cellular classification is, however, different from mine and his diagnosis is based rather on quantitative estimates. The increase of leucocytes during and immediately after menstruation and their decrease during the interval, as observed by Ramirez, are in accordance with the previous observations of Corner and Allen in monkeys and of King in the human being.

- ↑ A preliminary report on the same subject was published by this author in 1922, but unfortunately I have been unable to obtain the article.

Hartman, in his paper on gestation in Macacus rhesus (’28), presented some data on vaginal smear changes under normal conditions and during pregnancy. He found that the only successful mating in his Macacus took place at the ninth to twelfth day. During the fertile mating leucocytes were still present in the Vagina (though on the decline). Soon after copulation there was a temporary vaginal leucocytosis. He recognized two different types of leucocytes: those with unstained nuclei and those whose nuclei stained intensively with methylene blue. He stated that—

The total number of leucocytes increases during the second

half of intermenstruum, reaching a maximum just before (or

during) menstruation, whereas they go down to nearly zero in

the mid-interval; the curve of greatest desquamation from

the vaginal wall rises to a maximum in the latter part of the

interval, to fall, usually very low, about the time of menstruation.

This is in accord with Corner’s and Allen’s views. He also made observations on the cellular changes during gestation. He noticed the presence of the cells of Papanicolaou (navicular). He also found erythrocytes in the pregnancy smear for about 23 days, beginning at the twenty-sixth day since the onset of last menstruation (or 14; to 17 days after fertile

Plates

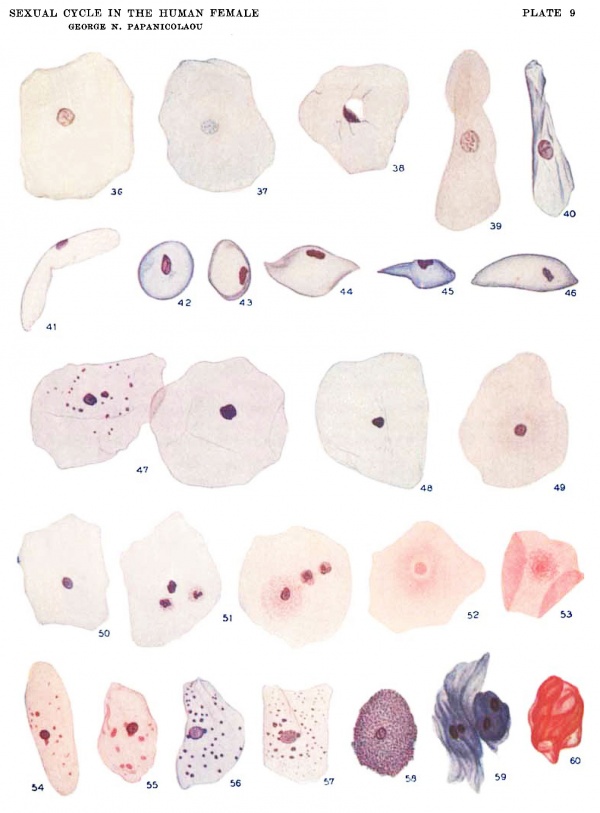

Plate 9

Drawings of various types of cells found in normal human vaginal smears.

- 36 to 60 Cells from human vaginal smears at different stages of the normal menstrual cycle.

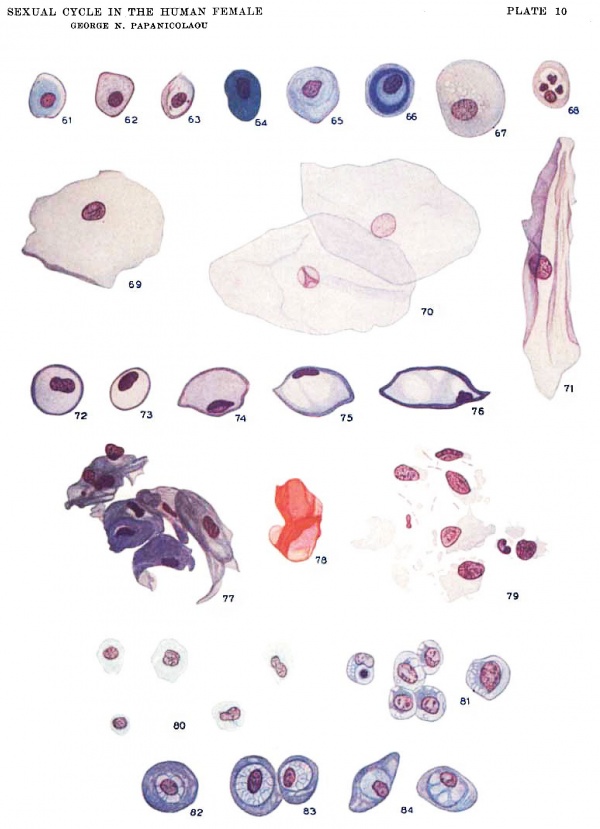

Plate 10

Drawings of various types of cells found in normal human vaginal smears.

- 61 to 68 Cells from human vaginal smears at different stagesrof the normal menstrual cycle.

- 69 to 79 Characteristic types of cells found in human vaginal smears during pregnancy.

- 80 Normal mononuclears during menstruation.

- 81 Large mononuclears found in post—partum.

- 82 to 84 Cliaraeteristic types of cells found in postpartum.

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, May 5) Embryology Paper - The Sexual Cycle in the Human Female as revealed by Vaginal Smears. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Paper_-_The_Sexual_Cycle_in_the_Human_Female_as_revealed_by_Vaginal_Smears

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G