File:Rugh 138.jpg

Original file (1,000 × 572 pixels, file size: 122 KB, MIME type: image/jpeg)

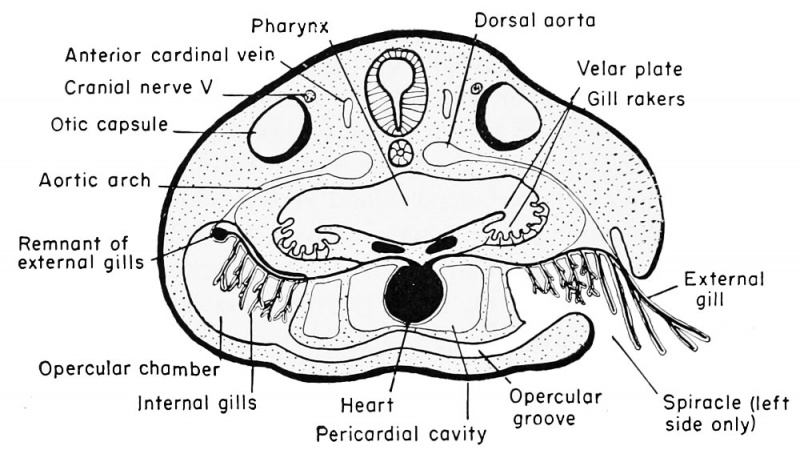

Relation of the pharynx to the internal and external gills of the frog, transverse section

Spiracle (left side only)

The finger-like and branched external gills arise as outgrowths of the lateral wall of the third, fourth, and fifth visceral (branchial I, II, III) arches shortly after the gill clefts are perforated. The first and second external gills arise at the 5 mm. stage and the third at the 6 mm. stage of development. The arches carry with them the covering ectoderm and the capillary loop of blood vessels and the nerves that are always found within the arches themselves. The ectodermal covering is very thin so that the relatively large capillaries in each gill can readily exchange CO._. and O.. in the surrounding aqueous medium. These external gills constitute the respiratory organs of the larva from about the fifth to the tenth days, and then the gills begin to atrophy. This process of degeneration is assisted by the development of a posterior growth from the hyoid arch, known as the operculum. This is a membrane which covers the gills and forms, along with a similar membrane of the other side, a ventral and ventro-lateral opercular chamber. While the external covering of the operculum is ectodermal it contains mesoderm. Water taken in through the mouth continues to pass over the external gills, within the opercular chamber, but escapes through the spiracle at the posterior margin of the left opercular fold.

In the meantime the internal gills must develop in order to take over the respiratory functions that gradually are being relinquished by the external gills. These internal gills develop a double row of filaments, ventral to the branchial arches and arising doubly from the postero-external (anterior and posterior) faces of the same first three pairs of branchial arches. These are visceral arches III, IV, and V. The fourth pair of branchial (sixth visceral) arches may also give rise to reduced single internal gills from their anterior faces only. These gills are termed internal because of their position on the arches and also because of the fact that they are covered by a body flap, the operculum, and are therefore truly within the body. The entire opercular (branchial) chamber is lined with ectoderm, however, and this includes the covering of all of the external and internal gills. The internal position of this new set of gill filaments is therefore secondary.

The ventro-lateral position of the external gills, plus the development of the operculum, tends to move them to a position beneath rather than lateral to the pharynx, within the spacious opercular cavity or chamber. The original endodermal branchial pouches, lateral to the pharynx, become partially separated off by lateral projections of the pharyngeal floor and also by longitudinal folds in the lateral aspects of the roof. This provides a lengthwise pair of pockets between the pharynx and the latero-ventral gill chambers. From the floor of each of these pockets develop finger-like, endodermally covered, frilled organs known as the gill rakers. These tend to filter the water as it passes from pharynx to gill chamber, removing any relatively large particles of matter and retaining them within the pharynx to be carried into the oesophagus with the food. In addition, the shelf-like projection or flap of tissue from the floor of the pharynx and also from the lateral wall of the pharynx likewise aid in the mechanical sifting or filtering of the water. These shelves are known as the velar plates. During subsequent metamorphosis both the gill chamber and the related opercular chamber become filled with rapidly multiplying cells which ultimately become incorporated into the body wall.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Reference

Rugh R. Book - The Frog Its Reproduction and Development. (1951) The Blakiston Company.

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 28) Embryology Rugh 138.jpg. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/File:Rugh_138.jpg

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 19:40, 14 April 2013 |  | 1,000 × 572 (122 KB) | Z8600021 (talk | contribs) |

You cannot overwrite this file.

File usage

The following 2 pages use this file: