File:Rugh 119.jpg

Original file (842 × 800 pixels, file size: 127 KB, MIME type: image/jpeg)

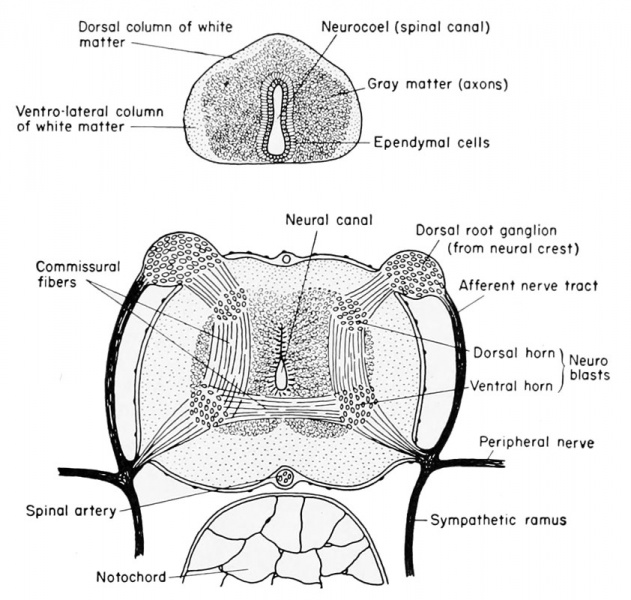

Development of the Spinal Cord of the Frog

- Top - Spinal cord of the 7 mm larva.

- Bottom - Spinal cord just before metamorphosis.

The neural or central canal (neurocoel) from the beginning of its development is laterally compressed by the thick lateral walls of the spinal cord derived from the original neural folds. The lining cells, coming from the dorsal epithelial ectoderm, retain both their pigment and their cilia, and are non-nervous in function. These cells, which continue to line the central canal of the adult, are known as the nonnervous ependymal cells. The thick lateral walls of the spinal cord are made up of the rapidly multiplying germinal neuroblasts (primitive or embryonic precursors of the neurons) and the supporting small and stellate cells known as the glia (neuroglia) cells. These cells have the function normally ascribed to connective tissue, namely support for the neuroblasts, but they are of ectodermal origin. The compact glia and neuroblasts close to the inner layer of ependyma comprise the gray matter of the cord. It is within this layer that the bulk of the cell bodies of neurons and the commissural fibers from one side of the cord to the other will be seen. As the cord develops further, the anterior and posteriorly directed fibers of the various neurons are concentrated more laterally so that only cross sections of axons will be seen. This peripheral area is then known as the white matter, to distinguish it from the more central and cellular gray matter of the cord. In addition to the lateral walls of the cord, which are thick, the dorsal wall is also thick because it consists of the fused neural folds.

The central canal or neurocoel is therefore displaced ventrally in the embryo and larva, but, as the cord is developed and more neuroblasts are formed, the neurocoel assumes a more central position. Within the enveloping connective tissue membrane which surrounds the spinal cord may be seen several blood vessels, principally the large spinal artery located in the mid-ventral (inverted) groove of the cord.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Reference

Rugh R. Book - The Frog Its Reproduction and Development. (1951) The Blakiston Company.

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 28) Embryology Rugh 119.jpg. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/File:Rugh_119.jpg

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 14:56, 14 April 2013 |  | 842 × 800 (127 KB) | Z8600021 (talk | contribs) | ==Development of the spinal cord of the frog== (Top) Spinal cord of the 7 mm. larva. (Bottom) Spinal cord just before metamorphosis. {{Rugh1951 footer}} Category:Spinal cord |

You cannot overwrite this file.

File usage

The following 2 pages use this file: