2011 Group Project 11: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

'''Neural crest cells forming craniofacial structures''' | |||

{|style="background:gold" border="1px" cellspacing="1" align="center" cellpadding="2" | {|style="background:gold" border="1px" cellspacing="1" align="center" cellpadding="2" | ||

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

|} | |} | ||

'''Non neural crest cells forming craniofacial structures''' | |||

{|style="background:gold" border="1px" cellspacing="1" align="center" cellpadding="2" | {|style="background:gold" border="1px" cellspacing="1" align="center" cellpadding="2" | ||

Revision as of 19:45, 14 September 2011

| Note - This page is an undergraduate science embryology student group project 2011. |

Cleft Palate and Lip

--Mark Hill 12:11, 8 September 2011 (EST) This project shows extremely poor progress at this time. May empty sub-sections and many of you have not met the requirements as required in an earlier laboratory assessment to add your content to the project page. Given the scope of your project topic there are an enormous number of resources, which have not been researched or utilised.

- Timeline would look better as bullet points with the date in bold as the first text.

- Only figure added is incorrectly named File:Pierre-Joseph_Desault-jpg.jpg. I had previously contacted and asked for this to be fixed and a citation added, neither has been done.

- I cannot provide you any further constructive comments at this stage, because there is insufficient for me to work with.

Introduction

--Mark Hill 12:10, 8 September 2011 (EST) There is no introductory text here.

- Cleft lip more prevalent in males

- Cleft palate more prevalent in females; 60:40 ratio females: males

- Neither age nor parity appear to be directly related

- Frequency of this birth defect is about 1 in 2,000 newborn in white populations

- It is higher in the Japanese

- lower in the Negro populations

History

In ancient times many congenital deformities, including the cleft lip and palate, were considered to be evidence of the existence of an evil spirit in the affected child. The reaction of the birth of a deformed child has varied widely from culture to culture where the infant was often removed from the tribe or cultural unit and left to die in the surrounding wilderness, a practise that was common in Antiquity and still happens today in certain parts of African tribes. In Sparta the unfortunate newborns were abandoned on Mount Tagete, while in Rome they were drowned in the Tarpeian rock.

The renowned philosopher Plato discussed it in one of his dialogues in the Republic, explaining that it was indeed a means of eradicating evil omens and preserving the soundness of the race.[1]

This state of lack of knowledge is evident up until 1889 when Keating published his opinion that a series of congenital anomalies were provoked in each case, by the mother looking at a person with similar deformity during her pregnancy.[2] The first persuasive explanation regarding the actual causation of the condition offered by Philippe Frederick Blandin between 1838 to1896 has revolutionised the perception of the condition. It sparked interest among physicians to investigate further into embryological development and the possible origin of clefting.[3]

Since 1896 to the 19th century both understanding and the surgery of cleft lip witnessed remarkable improvements. Surgeons around the world continued to research and propose refinements on the early procedure striving to accomplish precise and reproducible methods.

Timeline

- In 1295- 1351, Jean Yperman noted that cleft had a congenital origin classifying the various forms of the condition and outlining corresponding treatment principles. [4]

- In 1460, Heinrich von Pfolsprundt passed stitches through all the layers to repair the cleft instead of simply suturing the skin accomplishing a better repair of the lip. [5]

- In 1537-1619, Fabricius ab Aquapendente first described the embryological basis of cleft lip. [6]

- In 1561, Pierre Franco and Ambroise Pare described the techniques of correction of both unilateral and bilateral cleft lips in Traite des Hernies using dry sutures, pins and a triangular bandage. He emphasized that an accurate surgery procedure can produce an inconspicuous scar, an outcome which was “particularly desirable when the patient was a girl”.[7]

- In 1795, Pierre Joseph DeSault, a French pioneer of bilateral cleft surgery at La Charité and Hôtel-Dieu in Paris developed a new method for teaching anatomy and taught the procedure of bilateral cleft surgery[8]

- In 1808, Meckel pubished his theory of the embryological development of the lips which stated that the lips formed from five distinct processes which eventually united, three for the upper lip and two for the lower lip. [9]

- In 1838, Philippe Frederick Blandin suggested that facial cleft resulted from a failure of the premaxilla and the maxillary segments to unite at a later stage in development. [10]

- In 1844, Germanicus Mirault introduced a triangular flap from the lateral side into a gap created by making a horizontal incision on the medial side of the lip creating a nostril floor and reducing the linear scar on the lip. [11]

- In 1872, Jacob August Estlander, a Finnish surgeon introduced a method to correct the mid-face retrusion that was left by the bilateral lip repair process. He recommended a wedge resection of the vomer which allowed the protruding premaxilla to be pushed back. [12]

- In 1935, Faltin, another Finnish surgeon recommended that the procedure described by Jacob A Estander be abandoned because it routinely left serious maxillary retrusion. [13]

- In 1960, Peter Randall standardized the triangular flap repair method with accurate and reproducible measurements. [14]

- In 1965, W. M. Manchester introduced a procedure for the bilateral cleft surgery. [15]

- In 2000, Hua Xi Kou Qiang demonstrated that simultaneous primary palate repair and alveolar bone grafting are safe for unoperated cleft palate patients, and this procedure should be performed in unoperated cleft palate patients above 8 years old. [16]

- In 2008, J Y Wong published a study describing that craniofacial anthropometry using the 3dMDface System is applicable and reliable. Application of software algorithms merging the different overlapping images into a single three-dimensional image can remarkably improve landmark identification. [17]

- In 2010, B Mishra along with a team of Indian doctors published a study concluding that Nasoalveolar molding can be a useful adjunct for management of cleft lip nasal deformity. It serves as a cost-effective technique that can diminish the number of future surgeries such as alveolar bone grafting and secondary rhinoplasties in under developed countries. [18]

Neuroembryology and functional anatomy of craniofacial clefts

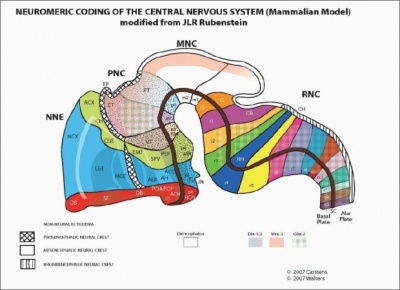

Embryological anatomy is the foundation upon which all treatment methods for craniofacial anomalies such as cleft must be based. Craniofacial clefts characterize states of inappropriate(excess or deficiency)distribution within and between specific developmental fields. The neuromeric mapping of the embryo is the primary denominator for understanding normal anatomy and pathology of the head and neck. [19]

The central nervous system of the human embryo develops in discrete segmental craniocaudal units called neuromeres. Specific genes known as Hox genes define the anatomical boundaries of each neuromere. [20]

The neural crest in each neromeric level is responsible for supplying it's specified zones of ectoderm and mesoderm; corresponding proteins are also expressed by the neural crest cells that complement the proteins secreted by the neural tube. The unique genetic markers associated with each neuromere can assist to identify the origins of craniofacial tissues that are eventually developed.[21]

The neuromeric model facilitates a precise mapping of the anatomical site of origin for the zones of ectoderm and endoderm supplied by a particular area of the nervous system. The density of neural crest cell population in these areas also can help us understand their individual roles in generating the structures they do.[22]

Neural crest cells forming craniofacial structures

| Neural Crest Cell Zone | Structure Generated |

|---|---|

| Premaxilla and Vomer | The rostral aspect of the second rhombomere (r2)[23] |

| The inferior turbinate, palatine bone, alisphenoid, maxilla and zygoma | The caudal aspect of the neural crest of rhombomere (r2))[24] |

| The squamous temporal, mandible, malleus and incus | The third rhombomere (r3)[25] |

Non neural crest cells forming craniofacial structures

| Non Neural Crest Cell Zone | Structure Generated |

|---|---|

| Cranial Base | PAM from somitomere 1[26] |

| Parietal Bone | Epaxial PAM from somitomeres 2 and 3 [27] |

Diagnosis

Cleft lip and palate occurrence varies among continents, races and populations from one in 700 to one in 1500 newborns. [28][29]

CLP is implicated to be related to more than 100 syndromes, and trisomy 13 is the most commonly associated chromosomal anomaly. Associated malformations occur most commonly in the facial region (21%), followed by the ocular system, central nervous system, skeletal system, cardiovascular system, neck, auricular system, gastrointestinal system and urogenital system[30]

While the birth of a child with CLP can have a severe emotional impact on the parents, antenatal diagnosis with ultrasonography helps to reduce the impact and prepare the parents psychologically. Most parents that received prenatal counselling following the diagnosis of CLP antenatally (85%) felt that the information had prepared them psychologically for the birth of their child, and 92% indicated that they had never considered the possibility of voluntary termination of pregnancy. Prenatal diagnosis of CLP has the additional advantage of allowing plastic surgeons to achieve early lip repair.[31] Prenatal ultrasound detection of the fetal face remains a matter of clinical research due to several technical difficulties associated with the examination of the fetus.[32]

The most exigent obstacles faced during CLP examination are as follows:

- shadowing effects of the superior alveolar ridge, and the fetal prone position[33]

- failure to identify the soft palate in three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound techniques as the soft palate is not in the same horizontal plane as the hard palate [34]

Cleft Soft Palate Detection

These technical challenges imply that the opportunity of prenatal screening for isolated defects of the soft palate is remote at present. Considering the additional time and effort involved in achieving satisfactory insonation and visualization, these methods are usually restricted to certain cases in which a cleft lip or hard palate is suspected. Isolated defects in the soft palate are relatively easier to repair surgically, and their emotional trauma on the parents if they are not diagnosed antenatally is far less severe than in newborns with cleft lip or cleft hard palate.[35]

Cleft Hard Palate Detection

A combination of three different methods of 3D ultrasounds has been tested to measure detection accuracy of hard palate anomalies (See Table 1 and 2). The three methods are:

- reverse face

- flipped face

- oblique face

To date, none of the three methods (reverse face, flipped face or oblique face) have been found to be notably superior to the others. Therefore a combination of all three tests should be carried out for any fetus provided that there are adequate volume acquisition and reasonable time to examine the images offline. However, in cases where an immediate diagnosis is required, the fastest method is the oblique-face approach. On the other hand when initial volume acquisition is inadequate and image quality is less than optimum, the reverse-face view or the oblique-face view in coronal planes is the most effective technique to use. [36]

Accurate ultrasound imaging of the secondary palate also requires the presence of fluid between the fetal tongue and palate, as well as curving of the plane so that the acquired volume follows the concave structure of the palate with either the oblique-face or flipped-face view. In some cases these views can reveal useful details about the soft palate which can be potentially be used in prenatal diagnosis of defects in future cases.

| Feature | Reverse-face view (% (n)) | Flipped-face view (% (n)) | Oblique-face view (% (n)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lip | 100 (10/10) | 100 (10/10) | 100 (10/10) |

| Alveolar ridge | 100 (9/9) | 100 (9/9) | 100 (9/9) |

| Hard palate | 71.4 (5/7) | 85.7 (6/7) | 100 (7/7) |

| Soft palate | 0 (0/7) | 14 (1/7) | 14 (1/7) |

Table 1. Percentage of fetuses with cleft lip and palate (n = 10) in which abnormal findings were well visualized using each technique [37]

| Feature | Reverse-face view (% (n)) | Flipped-face view (% (n)) | Oblique-face view (% (n)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lip | 100 (50/50) | 100 (50/50) | 100 (50/50) |

| Alveolar ridge | 100 (50/50)) | 100 (50/50) | 100 (50/50) |

| Hard palate | 78 (39/50) | 84 (42/50) | 86 (43/50) |

| Soft palate | 0 (0/50) | 16 (8/50) | 26 (13/50) |

Table 2. Percentage of fetuses with cleft lip and palate (n = 50) in which abnormal findings were well visualized using each technique [38]

Development of Disease

--Mark Hill 12:18, 8 September 2011 (EST) There is no text here.

Aetiology

--Mark Hill 12:18, 8 September 2011 (EST) There is no text here.

- Cleft lip and cleft palate often occur together however have different aetiologies

- Many factors cause this

- Possible interaction of indirect genetic factors with environmental factors, or perhaps environmental factors alone

- Cleft palate: 1 week delay in palatal shelve elevation in females, which occurs at week 8 as compared to week 7 in males

- Errors in development include inadequate growth of the palatine shelves, failure of the shelves to elevate at the correct time, an excessive wide head, failure of the shelves to fuse and secondary rupture after fusion

- Some mutations are linked to cleft palate and cleft lip

- Cleft lip: underdevelopment of the mesenchyme of the maxillary prominence and medial nasal process

- Pathogenic factors include inadequate migration or proliferation of neural crest cell ectomesenchyme, and excessive cell death during the developmental formation of the maxillary prominence and nasal placode

- Some common drugs which can cause the defect include phenytoin, Dilantin, vitamin A, and some vitamin A analogs

Developmental Staging

Development of the lip occurs during face development between weeks four and five. During this time the components that contribute to the face morphology come together and are fused to form a complete upper lip. These components include the maxillary processes and the medial and lateral nasal processes [39] At stage 15 the medial and nasal processes have started to fuse and the maxillary process lie inferior to them. During stage 16 the maxillary process and the medial nasal processes come in contact with each other and begin to fuse. Stage 18 is the later stage of lip formation. The maxillary process continue to grow and in doing so the force the medial nasal processes medialfrontally. It is between Stages 16 and 18 that a cleft lip is formed, after failure of the processes to fuse completely [39]

Development of the palate occurs between the seventh and tenth weeks. There are two main stages in palate development, primary and secondary. During the seventh week of development the intermaxillary processes are formed. These processes give rise to the primary palate. This primary palate contributes to the floor of the nasal cavity. Towards the end of the seventh week the palatine shelves, which were lying parallel to the tongue, start to move into a more horizontal position above the tongue. These palatine shelves begin to fuse with each other and with the primary palate. Fusion is complete by week ten and the secondary palate is formed. It is between weeks seven and ten of development that a cleft palate is formed as a cleft palate is the result of the palatine shelves failing to fuse properly. [40]

Types of Cleft Palate/Lip

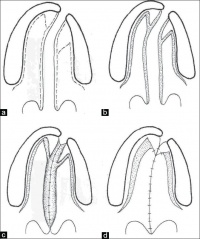

There are different types of both cleft palates and cleft lips, each with varying degrees of severity. Cleft palates and lips may either occur together or individually. Variations of cleft palate/lips include:

- Unilateral

- Unilateral cleft lip

- Unilateral cleft palate

- Unilateral cleft lip with a cleft hard palate

- Unilateral cleft lip with cleft hard and soft palate

- Bilateral

- Bilateral cleft palate

- Bilateral cleft lip

- Bilateral cleft lip with cleft hard palate

- Bilateral cleft lip with cleft hard and soft palate [41]

A cleft palate may be either complete or incomplete. It may also be unilateral or bilateral, and involve just the soft palate or include the hard palate as well.

There are many variations of a cleft lip. Cleft lips may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. A unilateral cleft lip presents with only one cleft, either complete or incomplete. As with a cleft palate, a cleft lip may also be incomplete or complete. The bilateral cleft lip may also be further divided into Binderoid bilateral complete cleft lip and palate, Bilateral complete cleft lip and intact secondary palate, Bilateral incomplete cleft lip and Asymmetrical bilateral (complete/incomplete) cleft lip [42]

Lesser forms of incomplete bilateral cleft lips can be divided into micro-form, microform, and mini-microform depending on the degree of the disruption at the vermilion-cutaneous junction [42]

Pathophysiology

There is no text here.

Genetic Configuration

There is no text here.

Treatment

- There are three major objectives of a cleft palate operation:

- To produce anatomical closure of the defect.

- To create an apparatus for development and production of normal speech.

- To minimize the maxillary growth disturbances and dento-alveolar deformities.

- Generally palatoplasty should be performed between 6-12 months of age however, there are many centres performing palatoplasty between 12-18 month and few who perform at least a part of the palatoplasty as late as 10-12 years.

- 3 palatoplasty techniques:

1. Hard palate repair techniques Veau-Wardill-Kilner pushback (V-Y) von Langenbeck bipedicle flap (W) Bardach’s two-flap (V) Alveolar extension palatoplasty (AEP) Vomer flap Raw area free palatoplasty

2. Soft palate repair techniques Intravelar veloplasty Furlow double opposing Z-plasty Radical muscle dissection Primary pharyngeal flap Two stage palatal repair

3. Protocol based techniques Schweckendiek's Malek's Hole in one

Complications include:

-Haemorrhage

-Respiratory obstruction

-Hanging Palate

-Dehiscence of the repair

-Oronasal fistula formation

-Bifid uvula

-Velopharyngeal Incompetence

-Abnormal speech

-Maxillary hypoplasia

-Dental malpositioning and malalignment

-Otitis media

Current and Future Research

There is no text here.

External Links

There is no text here.

Glossary/Terms

There is no text here.

Gallery

References

- ↑ Converse JM, Hogan VM, McCarthy JG. Cleft lip and palate. In: Converse JM, editor. Reconstructive Plastic Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1977. p. 1930

- ↑ Keating JM. Cyclopaedia of the diseases of the children. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1889.

- ↑ Blandin PF. Operation to remedy a division of the velum palati or cover of the palate. New York J Med. 1838;10:203

- ↑ Yperman J. La chirurgie de maitre Yperman mise au jour et annotee par JMF Carolus. Gand: F and D Gyselynch; 1854

- ↑ Pfolsprundt H von. Buch de Bündth-Ertsnei von H von Pfolsprundt Brunder de deutschen ordens 1490. Herausgegeben von H. Haeser und A Middledorpf, Reimer, Berlin:1868

- ↑ Bhattacharya S, Khanna V, Kohli R. Cleft lip: The historical perspective.Indian J Plast Surg. 2009 Oct;42 Suppl:S4-8. PubMed PMID: 19884680; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2825059

- ↑ Franco P. Traite des Hernies. Lyons: Thibauld Payan; 1561

- ↑ De Santo NG, Bisaccia C, De Santo LS, Cirillo M, Richet G. Pierre-Joseph Desault (1738-1795)--a forerunner of modern medical teaching. J Nephrol. 2003 Sep-Oct;16(5):742-53. PubMed PMID: 14733424

- ↑ Meckel JF. Beitrage zur Gesichischte des menschlichen Foetus. Beitr Verlag Anat. 1808;1:72.

- ↑ Blandin PF. Operation to remedy a division of the velum palati or cover of the palate. New York J Med. 1838;10:203

- ↑ Mirault G. Deux lettres sur l'operation du bec-delievre. J Chir. 1844;2:257

- ↑ Estlander JA. Eine method aus der einen lippe substanzverluste der anderen zu ersetzen. Arch Klin Chir. 1872;14:622

- ↑ Faltin R. History of plastic surgery in Finland. Finsk Lak Sallsk Handl. 1937;80:97

- ↑ Randall P. Triangular flap operation for unilateral clefts of the lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1959;23:331

- ↑ Manchester WM. The repair of bilateral cleft lip and palate. Br J Surg. 1965 Nov;52(11):878-82. PubMed PMID: 5842977

- ↑ Mao C, Ma L, Li X. [Simultaneous primary palate repair and alveolar bone grafting in unoperated cleft palate patients over 8 years old]. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2000 Oct;18(5):323-5. Chinese. PubMed PMID: 12539652

- ↑ Wong JY, Oh AK, Ohta E, Hunt AT, Rogers GF, Mulliken JB, Deutsch CK. Validity and reliability of craniofacial anthropometric measurement of 3D digital photogrammetric images. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2008 May;45(3):232-9. PubMed PMID: 18452351

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2916669/?tool=pubmed

- ↑ Indian J Plast Surg. 2009 October; 42(Suppl): S19–S34. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.57184 PMCID: PMC2825068

- ↑ Graham A, Papalopulu N, Krumlauf R. The murine and Drosophila homeobox gene complexes have common features of organization and expression. Cell. 1989;57:367–78[PubMed]

- ↑ Hunt P, Krumlauf R. Deciphering the Hox code: clues to patterning brachial regions of the head. Cell. 1991;66:1075–8. [PubMed]

- ↑ Indian J Plast Surg. 2009 October; 42(Suppl): S19–S34.doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.57184 PMCID: PMC2825068

- ↑ Indian J Plast Surg. 2009 October; 42(Suppl): S19–S34.doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.57184 PMCID: PMC2825068

- ↑ Indian J Plast Surg. 2009 October; 42(Suppl): S19–S34.doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.57184 PMCID: PMC2825068

- ↑ Indian J Plast Surg. 2009 October; 42(Suppl): S19–S34.doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.57184 PMCID: PMC2825068

- ↑ Depew MJ, Simpson CA, Morasso M, Rubenstein JL. Reassessing the Dlx code: Genetic regulation of branchial arch skeletal pattern and development. J Anat. 2007;27:501–61.

- ↑ Nowicki JL, Burke AC. Testing Hox genes by surgical manipulation. Dev Biol. 1999. pp. 210–238

- ↑ Gregg T, Bod D, Richardson A. The incidence of cleft lip and palate in Northern Ireland from 1980–1990. Br J Orthod 1994; 21: 387–392

- ↑ Coupland MA, Coupland AI. Seasonality, incidence and sex distribution of cleft lip and palate births in Trent region (1973–82). Cleft Palate J 1988; 25: 33–37

- ↑ Nyberg DA, Sickler GK, Hegge FN, Kramer DJ, Kropp RJ. Fetal cleft lip with or without cleft palate: ultrasound classification and correlation with outcome. Radiology 1995; 195: 677–684

- ↑ Martínez Ten, P., Pérez Pedregosa, J., Santacruz, B., Adiego, B., Barrón, E. and Sepúlveda, W. (2009), Three-dimensional ultrasound diagnosis of cleft palate: ‘reverse face’, ‘flipped face’ or ‘oblique face’–which method is best?. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 33: 399–406. doi: 10.1002/uog.6257

- ↑ Faure, J.-M., Bäumler, M., Boulot, P., Bigorre, M. and Captier, G. (2008), Prenatal assessment of the normal fetal soft palate by three-dimensional ultrasound examination: is there an objective technique?. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 31: 652–656. doi: 10.1002/uog.5371

- ↑ Rotten D, Levaillant JM. Two- and three-dimensional sonographic assessment of the fetal face. 1. A systematic analysis of the normal face. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2004; 23:224–231

- ↑ Faure JM, Captier G, B¨aumler M, Boulot P. Sonographic assessment of normal fetal palate using three-dimensional imaging: a new technique. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 29: 159–165

- ↑ Martínez Ten, P., Pérez Pedregosa, J., Santacruz, B., Adiego, B., Barrón, E. and Sepúlveda, W. (2009), Three-dimensional ultrasound diagnosis of cleft palate: ‘reverse face’, ‘flipped face’ or ‘oblique face’–which method is best?. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 33: 399–406. doi: 10.1002/uog.6257

- ↑ Martínez Ten, P., Pérez Pedregosa, J., Santacruz, B., Adiego, B., Barrón, E. and Sepúlveda, W. (2009), Three-dimensional ultrasound diagnosis of cleft palate: ‘reverse face’, ‘flipped face’ or ‘oblique face’–which method is best?. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 33: 399–406. doi: 10.1002/uog.6257

- ↑ Martínez Ten, P., Pérez Pedregosa, J., Santacruz, B., Adiego, B., Barrón, E. and Sepúlveda, W. (2009), Three-dimensional ultrasound diagnosis of cleft palate: ‘reverse face’, ‘flipped face’ or ‘oblique face’–which method is best?. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 33: 399–406. doi: 10.1002/uog.6257

- ↑ Martínez Ten, P., Pérez Pedregosa, J., Santacruz, B., Adiego, B., Barrón, E. and Sepúlveda, W. (2009), Three-dimensional ultrasound diagnosis of cleft palate: ‘reverse face’, ‘flipped face’ or ‘oblique face’–which method is best?. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 33: 399–406. doi: 10.1002/uog.6257

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 <pubmed>16292776</pubmed>

- ↑ The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology (8th Edition) by Keith L. Moore and T.V.N Persaud - Moore & Persaud Chapter Chapter 10 The Pharyngeal Apparatus pp201 - 240.

- ↑ M.J. Dixon, M. L. Marazita, T.H. Beaty , and J.C. Murray .Cleft lip and palate: synthesizing genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet. 2011 March; 12(3): 167–178

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 <pubmed>19884685</pubmed>

Textbooks

2011 Projects: Turner Syndrome | DiGeorge Syndrome | Klinefelter's Syndrome | Huntington's Disease | Fragile X Syndrome | Tetralogy of Fallot | Angelman Syndrome | Friedreich's Ataxia | Williams-Beuren Syndrome | Duchenne Muscular Dystrolphy | Cleft Palate and Lip