Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 17

| Embryology - 23 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

McMurrich JP. Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist. (1930) Carnegie institution of Washington, Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Leonardo da Vinci - The Anatomist

Chapter XVII The Nervous System

On QV, 6v there is a diagrammatic figure (fig. 71) drawn with red crayon and subsequently outlined with ink. It represents a sagittal section through the skull, with labels indicating the various structures cut, and is the translation into a drawing of a description by Avicenna. On the surface there are the hairs ( capigli ) of the scalp; beneath these a layer termed the codiga, corresponding to the epidermis and superficial fascia; then follow the galea aponeurotica, termed, however, came musculosa ; then the pericranium, the layer of areolar tissue being disregarded; then the bony cranium; then in succession the dura mater, pia mater and brain ( celabro ).

Nothing of the structure of the brain is shown except the ventricles, and these are represented as three cavities separated by constrictions and placed in a row, one behind the other, a prolongation of the anterior one extending to the eye and probably representing the optic nerve. In another figure on QV, 20 three ventricles are again shown but they are connected by short stalks or passages. A short stalk projects forward from the anterior one and quickly divides into the two optic nerves, while to the middle one are attached what are apparently inintended for the olfactory and auditory nerves. These and other similar figures with the ventricles in one, two, three order show the influence of mediaeval tradition, but on other folios there are figures which, while still very imperfect, approach nearer to the actual arrangement and suggest that they date from a time when Leonardo was relying on his own observations of an organ, which, without special preservation, presents many obstacles to dissection.

On QV, 8 there is a representation of the brain from the side which still shows three ventricles (fig. 72), but they have now quite different relations. The middle one has a short canal passing downward, presumably the infundibulum, and posteriorly it is connected by a short canal, which may be identified as the iter, with the posterior ventricle. From the anterior part of its roof a short canal arises which leads into a large crescentic cavity arching backward over the other two cavities. This is undoubtedly a lateral ventricle, but the figure shows no indication that it is a paired structure; Leonardo apparently had not yet reached that stage in the development of his studies of the ventricles. From the base of the brain, not from the ventricles, a number of nerves stream out, the optics with the eyeballs anteriorly, then a number of nerves from the region of the middle ventricle and still others from below the posterior one.

Fig. 71. Section through skull and brain showing brain membranes. (QV, 6v.)

Fig. 72. Ventricles of brain and cranial nerves. (QV, 8.)

Fig. 73. Ventricles of brain and view of its base. (QV,

On QI, 13v and on QV, 25 are figures that show a beginning appreciation of the paired character of the lateral ventricles, they being represented as paired in their posterior fourth, while for the rest of their extent they are a single cavity. On QV, 7 (fig. 73) the story is completed. One figure on that folio resembles closely that of QV, 25; in another the paired condition extends almost to the anterior extremity of the ventricles ; while in a third they are shown completely paired even as to the passageways connecting them with the middle or third, ventricle. This last figure, together with a companion one on the same folio, apparently represents the brain of an ox, seen from its basal surface, the rich plexus of blood-vessels (rete mirabile) surrounding the infundibulum, present in ungulate animals but absent in man, being clearly indicated. Possibly it is the figure of a brain that had been injected with wax (see p. 87), a supposition that might afford some explanation for the altogether erroneous form of the third ventricle.

These figures seem to form a series which illustrates clearly the development of Leonardo’s ideas of the ventricles, from a reliance on tradition to a reliance on personal observation. Whence Leonardo got the idea of three ventricles one behind the other is uncertain. It was not from either Avicenna or Mondino, since both these authors, following Galen, state distinctly that the anterior ventricle is paired. It may have been from a figure in the Philosophies naturalis attributed to Albertus Magnus and published at Brescia in 1490, or from one of the similar figures common in mediaeval manuscripts ( cf . fig. 8, p. 45). 1 The unpaired anterior ventricle is shown as late as 1504 in the Margarita Philosophica of Gregor Reisch, but in Peyligk’s Compendium (1499) it is represented as paired (fig. 6), its two cavities lying side by side, but in the same plane as the middle and posterior ventricles instead of above them, while Magnus Hundt in his Antropologium (1501) represents it (fig. 7) more crudely as consisting of two portions lying one behind the other.

Of parts of the brain other than the ventricles Leonardo gives little information. A small pencil sketch on QV, 7 shows the human brain viewed from above, the great longitudinal fissure being clearly shown and the sulci of the surface represented by scattered wavy lines, which give the general effect but not the actual arrangement. In the basal views of the brain of an ox (QV, 7) the temporal lobes of the cerebral hemispheres and the cerebellum are distinctly shown (fig. 73) and the infundibulum, cut across and surrounded by the rete mirabile , is indicated in one figure, while a T-shaped structure projecting from the third ventricle may represent the hypophysis. These, together with the ventricles, form the sum total of Leonardo’s contribution to the structure of the brain.

1 An excellent account of the early ideas as to the structure of the brain may be found in Jules Soury’s Le Systeme nerveux centrale, structure et fonctions, Paris, 1899, and the manuscript descriptions and illustrations of it have been discussed by Walther Sudhoff in his paper Die Lehre von den Hirnventrikeln in textlicher und graphischer Tradition des Alterthums und Mittelalters, Archiv fur der Geschichte der Medizin, Bd. 7, 1913.

True, there is a memorandum (QI, 13v) that the porosities of the brain substance are to be examined and one suspects that what were in mind were minute passages through which the vapors, supposed to be engendered in the brain, might escape. Mso, mention is made on QI, 3v of a vermis in the middle ventricle and on QIV, 11 it is described as a muscle which lengthens or shortens to open or close the passage from the third to the fourth ventricle. This is, of course, a fiction, probably adopted from Avicenna’s misunderstanding of Galen’s description of the vermis of the cerebellum.

But the mediaevalists and the early writers of the Renaissance were more interested in brain function than in brain structure. Galen had located the intellectual faculties in the brain substance in close proximity to the ventricles, which contained the psychic pneuma, but his successors, notably Poseidonius and Numesius, transferred their seat to the ventricles themselves. Galen held that the anterior part of the brain was of a softer consistency than the posterior, and associated this difference with a supposed relation of the softer sensory nerves with the anterior part and the harder motor nerves with the posterior part, and so the anterior ventricle came to be regarded as the center of sensation, the sensorium commune, as well as of the imaginative faculty {virtus fanlastica), which combined the sensations. Similarly the posterior ventricle was identified as the center from which the voluntary motor impulses originated, and at the same time as the seat of memory. The Galenic triad of faculties served for a time, but Avicenna, with somewhat of the penchant for metaphysical subleties that characterized Arabic thought, added to them existimatio, which would seem to mean judgment, though usually taken as equivalent to imagination, and associated this with cogitatio and referred them to the middle ventricle. Similarly he associated the sensus communis with phantasia, referring them to the anterior ventricle, while memory and motion were assigned to the posterior one. A crude representation (fig. 74) of this localization of functions is to be found in Reisch’s Margarita; it shows a primary triple division of the cerebral cavity and the concentration of all the special sensations in the anterior division or cellula, producing the sensus communis; behind this and connected with it are fantasia and imaginatio] estimatio and cogitatio are represented in the second or middle cellula and memoria in the third or posterior, the motor center being omitted. The figure from the Philosophica h'aturalis of Albertus Magnus shows a variant of this arrangement, imaginatio replacing fantasia in the anterior chambers and again appearing in the middle chamber, where it is associated with extimatio (sic), while memory and motion occupy the posterior chamber. Mondino furnishes another variant in that he locates fantasia in the anterior angle of the anterior ventricle, imagination at its posterior angle and the sensus communis between these two in its middle part. The middle ventricle takes care of cogitatio and the posterior of memory.

Fig. 74. Cerebral localization. From G. Reisch’s Margarita 'philosophise (Strassburg, 1504). After C. Singer: Fasciculo di medicina, part 1, fig. 69, 1925.

Other modifications might be mentioned 2 but these would merely emphasize what is already evident, namely, that the mediaeval writers based their ideas as to the activities of the brain mainly on Avicenna, who accepted Galen’s views as a foundation and built on them a superstructure less definite in the relations of its parts and therefore subject to differences of interpretation. Leonardo has his own interpretation. In one of his early figures of the ventricles (QV, 20v) showing their ground plan, the anterior ventricle has the legend imprensiva instead of phantasia, as if he desired to emphasize its receptive and combinatory functions; comocio, the legend for the middle ventricles is probably a misspelling of conoscio or conoscimento and the posterior one has memoria assiged to it. The fact that in QV, Gv he represents both the optic and auditory nerves as arising from the anterior ventricle, indicates his belief in the location in it of the sensus communis, but in other similar sketches (QV, 15 and 20v), while the optic nerves still take origin from the anterior ventricle, two other pairs, the olfactory and auditory, arise from the middle ventricle. Leonardo had evidently discovered that the great majority of the cranial nerves could not well be attached to the region of the anterior ventricle, the observation which led to this conclusion being probably that recorded in AnB, 35, where the anterior part of the base of the skull, seen from within after the removal of the brain, shows the position of the intracranial portion of the more anterior cranial nerves. Further, on QV, 8 is a sketch (fig. 72) that represents an accumulation of nerves below the floor of the middle and not the anterior ventricle. Here was a point in which Leonardo’s observations did not agree with tradition and he promptly disregarded tradition and transferred the origin of the sensory cranial nerves, except the optic, to the region of the middle ventricle, and as a result of this in QV, 15 he also transfers to that ventricle the sensus communis, and retains it in that location in his later figures (QV, 7). Indeed it would seem that he was even prepared to carry it still further back, for in a passage of text on the sheet just mentioned he expresses his belief that the sense of touch had its center in the posterior ventricle.

Having thus discarded the teachings of Avicenna and Mondino, Leonardo proceeds to give expression to his own theories as to the localization of function in the brain. In QV, 15 the posterior ventricle still bears the single legend memoria, but the other two have each a double legend. To the middle ventricle, in addition to senso commune, there is assigned also volunta, and the anterior one besides the legend inprensiva bears also that of intelletto. The association of the will with the sensus communis finds an explanation in QII, 18v, where the nerves are said to "move the members at the good-pleasure of the will (vol 1 These modifications have been tabulated by Walther Sudhoff in the paper referred to in the foot-note on p. 20a. unta ) of the soul” and the soul, in an earlier passage (AnB, 2), is located “in the judicial part (of the brain), and that seems to be the place where all the senses come together, which is termed the senso commune” The use of the word “judicial” suggests Avicenna’s faculty existimatio, and, if so, Leonardo had additional reason for transferring the senso commune to the middle ventricle.

The psychological significance of the faculties thus located in the ventricles is indicated in the following passage.

“Accordingly the joints of the bones obey the tendon ( neuro ), the tendon the muscle, the muscle the nerve ( corda ) and the nerve the senso commune. And the senso commune is the seat of the soul, memory is its admonition and the imprensiva is its referendary.” (AnB, 2.)

On AnB, 41 some measurements are given which serve to locate the relative position of the sensus communis. It is said to have directly below it at a distance of two fingers {i.e. finger breadths) the uvula, where the food is tasted, and it is above the tube of the lungs (i.e. trachea) and a foot’s length above the “foramen” of the heart. Above it, at the distance of half a head, is the juncture of the bone of the skull (sagittal suture) and on a level with it at a distance of one-third of a head is the “lagrimatoio” of the eyes and further to the sides the two temporal pulses. On QV, 2 is the further statement that the ventricles of the brain and those of the sperm (seminal vesicles) are equally distant from those of the heart.

Leonardo gives no description of the spinal cord ( nuca ), although he figures portions of it on several folios and on one (AnB, 23) shows a portion enclosed within its membranes. These are the same as those of the brain, pia mater and dura mater, but he states that in the spinal canal the dura is between the cord and the bony wall, apparently recognizing the difference of the arrangement of the spinal dura from that of the brain. He held, as the results of experiments on the frog mentioned on p. 91, that the cord was the center of life of the animal, and although his conclusions are not quite accurate, the observations are of interest, since they were the first experimental observations on the central nervous system since the time of Galen.

Nowhere are the nerves shown to arise by more than a single root, the discovery of the two roots, motor and sensory, not having been made by Volcher Coiter until 1573, more than fifty years after Leonardo’s death. There is no doubt that Leonardo, since he accepted the theory of the pneuma, believed the nerves to be hollow cylinders in whose lumina the pneuma might flow in either direction. Thus he says —

“These nerves ( corde ) having entered the muscles and lacertse command them to move; they obey and this obedience sets them in action so that they swell, and the swelling shortens their length and pulls back the tendons

(nervi ) that are interwoven with the particles of the member. Being infused in the extremities of the digits they carry to the sensorium the cause of their contact.” (AnB, 2.)

That is to say, they carry a knowledge of the object with which they are in contact. Further the term sensation ( sentimento ) is used for both efferent and afferent stimuli, for he states, for example, that the nerves that give stimulus ( sentimento ) to the intercostal muscles have their origin from the spinal cord {mica) (AnB, 30) ; and again — •

'‘The function of the nerve is to give a stimulus {sentimento). They are the knights (cavallari) of the soul and have their origin from its seat, and command the muscles that move the members at the good pleasure of the soul.” (QII, 18v.)

And yet in a passage on An A, 13 v it is implied that there are two kinds of nerves, those of sensation and those of motion, since it is stated that in injuries to the hand sensation in the fingers may be lost in some cases, but not motion, while in others it may be motion that is lost, but not sensation. Whether this statement was based on a personal observation is uncertain; it might have been a following out of Galen’s classification of nerves, repeated by Avicenna, in which “hard” (motor) and “soft” (sensory) nerves were recognized, the latter being associated with the anterior softer portions of the brain and the former with the harder posterior portion and spinal cord. Leonardo seems to have accepted the idea of differences of consistency in different parts of the brain, for he made a memorandum to enquire whether the region whence the vagus nerve took origin was hard or soft, with the object of determining whether that nerve was motor or sensory (AnB, 33 v).

The idea that the nerves were bundles of fibers had not developed in the sixteenth century. For Leonardo each nerve was a tubular prolongation of the substance of the central nervous system, invested by coverings from the pia and dura mater, the prolongation of nerve substance being continued through all the 'ramifications of the nerve —

“and each fiber of the muscles is enclosed within an almost imperceptible membrane into which the ultimate ramifications of the said nerve are converted, these nerves obeying (commands) to shorten the muscle by retracting and to dilate it at each command of the stimulus {sentimento) that passes by the lumen of the nerve.” (AnB, 23.)

In some passages, however, Leonardo expresses himself carelessly, giving the impression that he thought the nerve to be a cylindrical projection of the pia mater. Thus in the continuation of the passage just quoted he states that the pia mater on emerging from the spinal canal becomes converted into a nerve, and on AnB, 35 it is asserted that “the nerves arise from the last membrane {i.e. the pia) which invests the brain and spinal cord.” But such statements must be interpreted as merely meaning that the pia is continued out over the nerve as an investment, the nerve itself being a prolongation of the nervous system. On AnB, 17v there are two sketchy representations of the entire nervous system and accompanying them is the inscription “Tree of all the nerves, which shows how they all have origin from the spinal cord ( nuca ) and the spinal cord from the brain.”

Fig. 75. Figure showing course and distribution of reversive (vagus) nerve. To right a longitudinal section of trachea. (AnB, 33v.)

The cranial nerves are shown in several figures (QI, 13v; QV, 8) as a mass of cords depending from the floor of the middle ventricle (fig. 72), but few of them can be identified. The olfactory tracts are best shown in a view of the base of the skull (AnB, 35) and in this they are somewhat dilated at their extremities to form the olfactory bulbs. They are called caroncule, a term used by Mondino, but hardly applicable to the human tracts; probably it traces back to the olfactory lobes of some lower animal. In some figures the tracts are attached well forward on the brain, but in others they pass back to the region of the middle ventricle. The optic nerves are also connected with the anterior ventricle in some figures, but in others they are more correctly related to the middle one and in such cases their union to form the commissure is distinctly showm, although the commissure is quite separate from the floor of the ventricle.

Galen and, following him, Avicenna, enumerate the oculomotor nerves as the second pair in their list of the cranial nerves, but the other two pairs to the muscles of the orbit, the trochlearis and abducens, were overlooked. In a figure of AnB, 35 Leonardo shows, in addition to the optic nerve, two or three others passing forward toward the eye ball, on the surface of which one of them branches. They can not be certainly identified with the three motor nerves of the orbit, but it would seem that Leonardo had observed at least one of the nerves that Galen overlooked. However, Leonardo was evidently somewhat uncertain about these nerves for he has a memorandum on QIV, 11 suggesting that he should —

“Search for the motor nerves of the eyes and consider if the principal ones are four more or less, because in the infinite movements (of the eyes) four nerves do all, since as you leave the jurisdiction of one, aid comes from the second.”

Of the remaining cranial nerves the only one to receive particular attention is the vagus, which Leonardo terms nervo reversivo, applying to the entire nerve a term applicable only to one of its branches. On AnB, 33v (fig. 75) the right vagus is shown descending from the base of the skull in company with the carotid artery and internal jugular vein. It passes under what may be regarded as the subclavian vein and gives off the recurrent branch wdiich runs upward over the vein to supply the trachea and larynx. Below this the main nerve continues downward, the text accompanying the figure stating that —

“ hf is the nervo reversiuo descending to the porlinario of the stomach. And the left nerve, the companion of this, descends to the envelope of the heart and I believe that it may be the nerve that enters the heart.”

The course of the recurrent nerve is rather feebly explained as protecting it from injury when the neck is bent forward (QI, 13v), and it would seem that Leonardo was uncertain as to the relations of the left nerve, for he adds a memorandum to “enquire in what part the left nervo reversiuo turns and what is its function,” adding a further query as to the manner in which “the nervi reversivi give sensation {sentimento) to the rings of the trachea.”

Leonardo’s interest in the spinal nerves was concentrated mainly on those that pass to the limbs. Of the intercostal nerves he barely makes mention (AnB, 30), stating that they arise from the spinal cord, the lowest one having its origin at the level of the kidney; and of the nerves from the cervical plexus he figures only the phrenic (AnB, 33v and 34), which he traces from the fifth cervical nerve, instead of the fourth, to the pericardium, failing to note its continuation to the diaphragm, although its connection with that muscle had been shown experimentally by Galen and is mentioned by Avicenna.

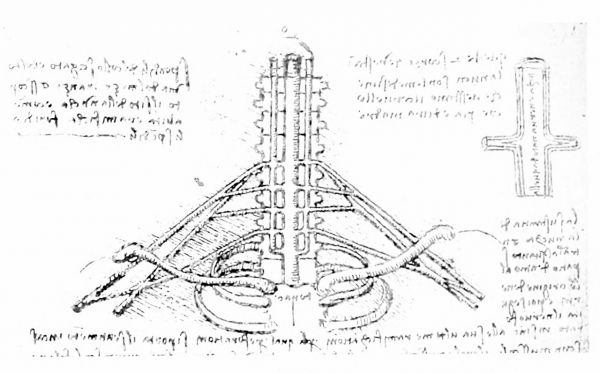

There are a number of attempts at representation of the brachial plexus but in none of them are its complexities correctly elucidated. In the majority of figures (An A, 4v, 23, 23 v; QV, 21v) but four nerves enter into its formation (fig. 7G), the participation of the first thoracic being overlooked, but in that on AnB, 3v (fig. 77) five nerves are shown and, furthermore, the three main divisions of the plexus are correctly represented. The rearrangement of the fibers to form the three cords is not, however, clearly shown, although the posterior cord may be identified. Leonardo, of course, could have no idea of the significance of the plexus as a means of distributing the preaxial and postaxial fibers — the fibers were unknown to him — and he seems to have supposed it to be an arrangement for the continuance of function in case one or more of the nerves should be injured, since he has a memorandum to enquire which of its five branches would suffice to give sensation to the arm, if the others were destroyed by a sword wound (AnB, 3v).

The three main nerves of the arm, median, ulnar and radial, are shown in several figures so far as their general course is concerned, but their origin from the plexus is lacking in accuracy. Other nerves are also indicated, such as the axillary passing to the omero (deltoid), the musculo-cutaneous to the pesce del brachio (biceps humeri) and what may be the antibrachial cutaneous (AnB, 23v) and the deep radial (AnB, 3v). The courses of the three principal nerves with reference to the bones of the arm are well shown on QV, 21 and 21v, and it should be mentioned that the course of the ulnar nerve behind the medial epicondyle of the humerus is distinctly indicated on AnB, 23 v, and that its cutaneous distribution on the volar surface of the hand, as well as that of the median, is correctly represented in the same figure and still better on AnB, 8v.

Fig. 76. Figures showing arrangement of brachial plexus. (AnB, 23v.)

Fig. 77. Another figure of t he brachial plexus. (AnB, 3v.)

Fig. 78. The lumbo-sacral plexus. (AnB, 6.)

The lumbo-sacral plexus is in worse case than the brachial, the figures that represent it (AnB, 6; QV, 9 and 21) being evidently based on animal dissections and representing only four nerves participating (fig. 78). In the figure on AnB, 6 three nerves are shown arising from the plexus, one of which, passing over the pubis, being evidently the femoral, a second, the obturator, passing through the foramen so designated, while the third, passing down into the pelvis probably represents the sciatic. In the figure on QV, 21 (fig. 78), the obturator is not shown and the femoral divides into two branches, one of which is distributed to the thigh, while the other passes down behind the medial condyle of the femur and appears to represent the long saphenous, a nerve which seems to have especially attracted Leonardo’s attention. On QV, 20 v (fig. 79), is a figure representing the leg from the inner surface; it shows the sartorius muscle, labeled lacerto, and along its medial border are two cords labeled nervo and vena. Both these structures are continued downward as far as the foot, the nerve ending at the level of the medial malleolus while the vein passes to the sole of the foot. It seems probable that this nerve and vein are to be regarded as representing the long saphenous and the internal saphenous, but representing them somewhat incorrectly, since, in the thigh the nerve actually lies beneath the sartorius and the vein superficial to it, and the vein arises on the dorsum of the foot, not in its plantar surface. 3

The long saphenous nerve is also shown in other figures, as, for example, in two silver-point drawings on QV, 19. In one the nerve, accompanied by a blood-vessel, lies under cover of the sartorius muscle ; in the other the muscle is cut across and reflected and the nerve and blood-vessel are shown passing down side by side as far as the knee, where they lie behind the medial condyle. The nerve and the accompanying blood-vessel with the sartorius cut away are again shown on AnB, 18, the vessel being here probably the femoral artery, and on QV, 15 the same vessel is shown accompanied by a branch of the femoral nerve, which divides into the long saphenous and a branch to the vastus lateralis.

The great sciatic nerve is shown on QV, 15, issuing from the great sacro-sciatic foramen. It passes down the back of the thigh and divides below into a peroneal branch, which inclines laterally, and a tibial branch that continues straight downward. The same branches are shown on QV, 10, and again on QV, 9v and AnB, 5, the peroneal in these last two sending a branch to the dorsum of the foot. On AnB, IS there is a representation of the sacral plexus, into whose formation the last lumbar and first and second sacral nerves enter and from which two nerves arise and pass down the leg parallel to one another and finally pass to the sole of the foot, bending around the malleoli ( nod dei piedi). This may represent a high division of the sciatic, such as is occasionally seen, but even so the passage of both branches into the sole of the foot is inaccurate. A high division of the sciatic is also shown on QIV, 9 (fig. 80).

3 Holl (1917) identifies the nerve in its upper part as the femoral and in its lower part as the posterior tibial. It is difficult to believe that Leonardo could have fallen into such confusion and the identification with the saphenous seems more probable, especially since the nerve is not continued into the sole of the foot.

The ganglionated cord of the so-called sympathetic nervous system was known in part of its course to Galen and was regarded by him as a branch of his fourth pair of cranial nerves. Avicenna merely mentions it as a part of the fourth pair, indeed it would hardly be recognizable from his statement without reference to Galen, and Leonardo might well be pardoned if he failed to notice it. Yet it seems that he did observe it, even though he failed to perceive its correct relations. On AnB, 23 are two figures (fig. 81) that represent the cervical portion of the spinal cord and the nerves that arise from it to form the brachial plexus. On issuing from the spinal cord each nerve makes connection with a slender cord that runs upward, parallel to the spinal cord, to unite with the brain. These slender cords are again shown on AnB, 4 and 4v, and on QV, 8. One is at first inclined to identify them with the vertebral artery, since in some figures they are represented as passing through foramina in the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae. This possibility is negatived partly by the fact that the nerves are continuous with the cords, and partly by a figure on QV, 21, in which the foramen for the cord is represented as quite separate and distinct from that for the vertebral artery, this latter foramen being labeled “passage-way for the animal virtue.”

IIoll (1917) and Ilopstock (1919) agree that the cords can not represent the vertebral arteries and while Hopstock regards them as phantasies, IIoll gives them terminological entity as the nervi intertransversarii and suggests that Leonardo had borrowed them for some ancient unknown source, in which prolongations of the brain substance had been described as occupying the place of the vertebral arteries. It is to be noticed that all the figures showing the cords are evidently diagrammatic; they do not represent actual preparations, though based on dissections; they arc products of the study rather than of the laboratory and it is more than a possibility that the cords are portions of the ganglionated cords, the recollection of which had been more or less confused with memories of the vertebral arteries.

Fig. 79. Figure showing course of long saphenous nerve. (QV, 20v.)

Fig. 80. Branching of common iliac vessels and sciatic nerve. (QIV, 9.)

Fig. 81. Cervical portion of spinal cord, showing origins of spinal nerves and what may be a suggestion of ganglionated cord. (AnB, 23.)

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Reference: McMurrich JP. Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist. (1930) Carnegie institution of Washington, Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore.

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 23) Embryology Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 17. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Leonardo_da_Vinci_-_the_anatomist_(1930)_17

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G