2014 Group Project 9

| 2014 Student Projects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 Student Projects: Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | Group 6 | Group 7 | Group 8 | ||||

| The Group assessment for 2014 will be an online project on Fetal Development of a specific System.

This page is an undergraduate science embryology student and may contain inaccuracies in either description or acknowledgements. | ||||

Genital

Historic Finding

Female Genital Development

Female genital system development has been a subject of many historical literatures dating to the 17th century. Certain research articles aimed to focus on the female genital system as a whole, whereas others delved into specific areas such as the epithelium or specific organs such as the vagina. With the development of technology and research skills over the years, the understanding of the female genital system has improved substantially from the understanding of origin, the structure of the organs and even the nomenclature of the system. [1] [2]

Majority of the findings lead to a proposal of a theory of that organ or the system, with some of these theories still accepted today and others disproven. The research themes and theories found in historical literature can be divided into three groups. [1]

- The origin of the vagina and inner genital organs is the Mullerian duct.

- Part of the Wolffian ducts give rise to some or all of the vaginal epithelium.

- Contribution of the vagina is from the epithelium of the urogenital sinus.

Prior to the discovery of the importance of the Mullerian ducts, the origin of the vagina was considered to be the urogenital sinus. It was not until later that century, roughly in 1864 that the Mullerian ducts and their fusion pattern and foetal development was introduced. This realisation was later supported by many academics in their published work, particularly in the early 1900s (1912, 1927, 1930, and 1939). [1]

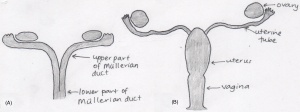

According to the works of the early embryologists Thiersch, Banks, Felix, Bloomfield & Frazer, Hunter and von Lippmann, all who published within the timeframe of 1868 to 1939, concluded that the mullerian (paramesonephric) ducts, found laterally to the wolffian ducts, are the original structures of the female reproductive system. Female sexual organs (the fallopian tubes, uterus and vagina) originate from the mullerian ducts, which differentiates within the foetal developmental phase. Initially the foetus contains two mullerian ducts, however by the ninth week, fusion of the lower portion of the ducts is complete, creating the fundamental structure of the uterus and the vagina, however the these two organs are not continuous with the vagina being solid. The non-fused upper part of the ducts emerge into the fallopian tubes. It is not until the fourth and fifth month of development that the uterus becomes continuous with the vagina, with both organs developing a hollow lumen. The muscular layers of the uterus is also present by this stage. The cervix begins to form within the fifth month in between the continuous vagina and uterus. Also within the same month, the formation of the hymen occurs. The hymen is described as a pouting vertical slit and represents the remains of the mullerian eminence. [3] [4]

Male Genital Development

The Prostate

The mechanism behind prostate foetal development and modern understanding has been continuously reshaping since the 16th century. Throughout this period, various anatomical classifications have been proposed via dissection procedures, hormone responses and histological methods, attributing to the current understanding of prostate development. The rate of research into the structure and development of the prostate steeply increased in the 20th century, where each decade saw an improvement of the understanding of the development of the gland. [5] [6]

| Date | Description |

|---|---|

| 1543 | Andreas Vesalius published the first illustrations of the prostate gland. |

| 1674 | Gerard Blasius introduced the gland as a structure encircling the neck of the bladder. |

| 1901 | Pallin thoroughly investigated the prostate gland and its origin. |

| 1912 | Oswald S Lowsley constructed the first detailed drawing of the anatomy of the prostate by dissecting and researching on a 13-week old foetus, 30-week old foetus, and one at full-term. He proposed the concept of separating the gland into five lobes, and that the prostate originates from the urogenital sinus. |

| 1920 | Johnson reshaped the anatomical illustration after being unable to replicate Lowsley’s results. He preserved the use of the term ‘lobe’ in describing the prostatic divisions. |

| 1954 | Three concentric regions became the accepted categorising model of the prostate, as proposed by Franks. |

| 1983 | McNeal organised the gland into prostatic zones, rejecting the lobe and concentric regions theory. |

Testicular descent

Testicular descent begins during the early foetal period, 8-10 weeks, and takes approximately 5 weeks for the testes to reach the inguinal region. The second phase of descent, when the testes reach the scrotum, is not complete until the 35th to 40th week. The mechanisms behind testicular descent has been debated for at least two centuries, beginning with anatomical dissections during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, then enhancing with endocrinological discoveries during the twentieth century.

The Scottish surgeon and anatomist, John Hunter, first documented the gubernaculum and the location of the male foetal testicles in the late 1700s. In his research, Hunter claimed that descent occurred during the 8th foetal month and was directed by the gubernaculum testis, a ligament attaching the foetal testis to the abdominal wall and the scrotum. He further proposed that the processus vaginalis closes subsequent to the decent of the testis. This is contrary to the findings of Albrecht von Haller who illustrated that foetal testis is intra-abdominal and the processus vaginalis is not closed.

Hunter described the gubernaculum as a vascular and fibrous foetal structure covered by the cremaster muscle, a muscle of unknown function. This led to more research focused on the cremaster muscle. In 1777, Palletta questioned the importance of the cremaster muscle because of its under developed state during the time of descent. This however did not stop Pancera, who in the following year, considered the muscle as the key factor in the process. Pancera’s conclusion was confirmed by Lobsetin in 1801.

The second phase of testicular descent to the scrotum has also seen many theories. Lobsetin suggested that this phase is complete by birth, influenced by respiration and the increased abdominal pressure that occurs at birth. The concept of increased abdominal pressure was reiterated by Robin in 1849, however he also introduced the theory that descent into the scrotum occurs due to the weight of the testes and muscles associated. Both Lobsetin and Robin’s work was refuted by Weber who highlighted the processus vaginalis, an embryonic pouch of peritoneum, as the main force of the migration.

In 1841, Curling detailed the structure of the gubernaculum and the cremaster muscle. Curling believed that during the foetal period, the cremaster muscle was important in descending the testis, however subsequent to the descent, the fibres of the muscle everted resulting in it’s new functions of elevating, supporting and compressing of the developed testis. The eversion of the muscle fibres were denied by Cleland, who in 1856 performed dissections on foetal specimens ranging from 5-6 gestational months old. In his experiment he found that the foetal gubernaculum did not directly attach the testicle to the scrotum and was only present in the inguinal wall. In terms of the testicular descent process, Cleland presented a similar theory as Weber, in terms that the cremaster was not the primary source of descent, second to the gubernaculum, that led the descent of the testes. In 1888, Lockwood published a completely unique theory claiming that the testes remained stationary and that it was in fact the surrounding structures that developed, resulting in the changing of the testicular location. Lockwood’s hypothesis was disagreed on by many anatomists and embryologists.

With the introduction of endocrinology and hormonal testing, the previous theories were tested on a cellular basis. Male androgen, controlled by the pituitary gland, was the first hormonal theory believed to influence testicular descent. It has been evidently proven that androgens are important in the descent however it is unclear if it is important in both stages. It is currently accepted that testosterone influences the gubernaculum during the second phase in which the testes reach the scrotum, however the exact method is currently debatable. The first phase theories are under high scrutiny, with theories ranging from the development of the gubernaculum and hormones such as the Mullerian inhibiting substance. [4]

References

4. Martyn P. L. Williams, John M. Huston The history of ideas about testicular descent. Pediatric Surgery International: 1991, 6(3):180-184 The history of ideas about testicular descent

<pubmed>18462432</pubmed> <pubmed>17232227</pubmed>