Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 4

| Embryology - 18 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

McMurrich JP. Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist. (1930) Carnegie institution of Washington, Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Leonardo da Vinci - The Anatomist

Chapter IV Anatomical Illustration before Leonardo

Great as is the interest attaching to Leonardo’s notes as indicating the anatomical problems for which he sought solutions and the methods he adopted in his attack upon these problems, greater still is the interest associated with his illustrations, partly because they are largely records by a consummate master of art of what he had himself observed and partly because of the great importance he attached to illustration as a didactive method. In several passages he expresses his conviction that for a correct appreciation of the form of any structure one must view it from various aspects, and he vaunts the value of such illustrations over mere description. Thus he says —

“Oh Writer! with what words will you describe the entire configuration with the perfection that the illustration here gives? This, not having knowledge, you describe confusedly and allow little information of the true form of the things, deceiving yourself in believing that you can satisfy the auditor in speaking of the configuration of any corporeal object, bounded by surfaces. But I remind you not to involve yourself in words, unless you are speaking to the blind, or if, however, you wish to demonstrate by words to the ears and not to the eyes of men, speak of substantial or natural things and do not meddle with things pertaining to the eyes by making them enter by the ears, for you will be very far surpassed by the work of the painter. With what words will you describe the heart without filling a book, and the more you write at length, minutely, the more you will confuse the mind of the auditor. And you will always have need of expositors ( sposilori ) or of a return to observation (alia sperientia ) , which with you is very short and gives knowledge of few things as compared with the whole subject of which you desire full knowledge.” (QII, I .) 1

These are the words of one who is able to speak more eloquently with his pencil than with his pen. His anatomical manuscripts are primarily collections of drawings, the accompanying notes being secondary additions, suggestions of further illustrations that seem necessary, or of problems that require further elucidation by observation. The drawings vary greatly in their finish. Many are sufficiently elaborated as to require no further treatment, others are outline drawings still requiring finishing touches, others again, are frankly diagrammatic; while others are merely crude suggestions — memoranda of themes to be more fully elaborated later. Of the more finished drawings three main types may be recognized. Firstly those that are

1 Compare passages on An A, lv and 14v.

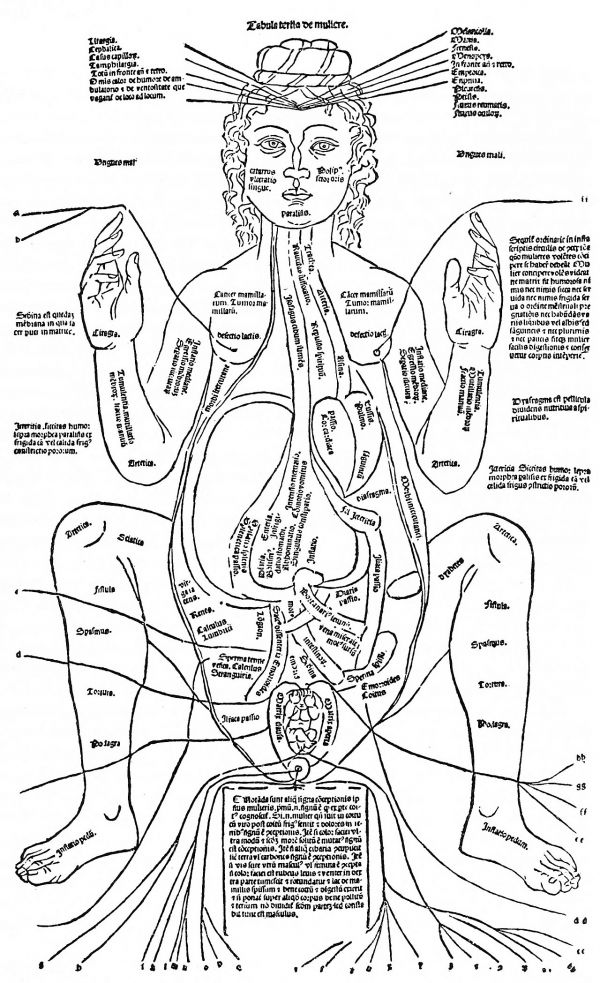

Fig. 3. Situs figure from the Fasciculus medicinse (1491). After the facsimile published by K. SudhoS and C. Singer, Milan, 10, 1924.

representations of his personal observations, without modifications due to preconceived notions. Of these there are many examples, many that might be selected as suitable for illustration of a modern text-book. But Leonardo was no more infallible than is a modern anatomist and, furthermore, he was a pioneer in anatomical illustration. Consequently one may note that his observation is not always as accurate as might be desired; he pictured what he saw, but sometimes his investigation was not carried far enough and he allowed himself to portray structures as tradition taught them to be. Such drawings constitute the second type, and the third consists of those in which he fell into the same errors as did Galen, by assuming that structures seen in animal dissections were identical with those of the human body. Thus he figured the hyoid bone of a dog in a human throat (fig. 67), 1 the cotyledons of a cow’s placenta in that of a human being (fig. 87) and represented the heart of an ox as that of a man. Leonardo appreciated the fact that so far as the musculature and skeleton were concerned, the different conditions in animals required modification of the human plan. But where the functional demands on organs seemed to be identical, it seemed permissible to suppose that their structure would also be identical, since he believed that "Nature always produces its effects in the easiest way and in the shortest time that is possible” (QI, 4), and that "The Author never makes anything superfluous nor defective” (Q II, 3) — what would serve in one case would, therefore, serve in another similar case.

But one may forgive Leonardo’s inaccuracies because he was doing the work of a pioneer, because, even with them, he was representing the structures of the human body with an accuracy and skill such as never had been seen before and because he was the originator of a revolution in anatomical illustration which was to play an important part in establishing the foundations of modern anatomy.

The earliest printed figure showing the anatomy of the internal organs is that in the 1491 edition of Ketham’s Fasciculus Medicines , 2 published two years after Leonardo had definitely become immersed in his anatomical studies. A glance at the figure (fig. 3) shows that it is highly conventionalized, not one of the organs showing its true form or relations; even the crouching posture, with the arms flexed so that the hands are on a level with the shoulders, smacks of conventionalism and suggests the possibility that the figure is a reproduction of some earlier drawing. This probability has been made a certainty by the researches of K. Sudhoff, who with exceptional skill and ingenuity has traced it to its origin, reconstructing an interesting chapter in the history of anatomical illustration. 3 He found in the Hof- und Staatsbibliothek in Munich a manuscript (Codex monacensis germanicus 597) whose contents are chiefly astronomical and astrological, but which includes also a certain amount of gynecological and obstetrical material. It bears the date 1485 and is of interest in the present connection from the fact that on one of the pages there is a water-color drawing of a female figure, strikingly similar to the Ketham figure of 1491 and showing the viscera. It shows a similar crouching posture with the hands up-raised, but, instead of the turban seen in the Ketham figure, the head is covered by a coif. The representations of the viscera are very similar in the two figures, that of the Munich Codex showing the intestines in greater detail and, in order that the rectum may be more clearly shown, having the uterus displaced toward the left; it is noteworthy that the posture of the fetus, with the hands covering the eyes is unaltered. If any doubt could exist as to the common origin of the two figures it would be dispelled by the fact that the legends borne by the various organs are for the most part identical.

- In his preface to the facsimile reproduction of this work Sudhoff has suggested that Ketham was a corruption of Ivirchheim. There was a Johannes von Kirchheim professor of surgery at Vienna, 1445-1470.

Sudhoff also records the occurrence of a figure almost identical with that of the Munich Codex in a manuscript in the possession of Dr. Gustav Klein of Munich and has found another example of a similar figure in a manuscript in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris (Ms. Lat. 11229), written some time during the reign of Charles VI (1380-1422). The crouching posture has disappeared in this last figure and the uterus contains two fetuses, but otherwise both figure and legends are essentially identical with those of the Munich Codex. Finally, Sudhoff traces these various figures to one found in a manuscript (Cod. 1122) in the library of the University of Leipzig, dating to approximately 1400. In this the crouching posture is quite marked, the kidneys, omitted in the Munich Codex, are represented and the uterus has its position in the median line, the contained fetus having the characteristic attitude already mentioned. No legends occur in the various parts of this figure.

It is evident then that the figure representing the situs viscerum of the female printed in the 1491 edition of Ketham’s Fasciculus is a reproduction of a figure that had been in use for at least almost a century and from the first had represented the various organs in a highly conventionalized manner. Nor is it even a faithful reproduction of its prototypes, but was evidently drawn by one unfamiliar with human anatomy, so that the original conventionality became still more conventionalized. It is worthy of note, however, that the figure throughout its history was not accompanied by an anatomical description of the parts delineated. Some of the accompanying legends are names of the parts represented, but the majority are the names of diseases, such as passio iliaca, idericia, podagra, etc., which have their seats in the parts indicated; it is a pathological rather than an anatomical illustration. The Ketham Fascicidas of 1491 contains no anatomical treatise; Mondino’s Anathornia was added to the original medical treatise in the editions of 1493 and 1495, and while the figure, still further modified, appears in these, it illustrates the medical treatise and not the Anathornia.

3 Sudhoff’s studies are to be found in a series of papers published in the Archiv and Studien zur Geschichte der Medizin. An interesting account of early anatomical illustrations has been given by W. A. Locy in his paper entitled Anatomical Illustration before Vesalius (Jour, of Morphology, vol. 22, 1911) and important data are also to be found in F. Wieger’s Geschichte der Medizin und ihrer Lehranstalten in Strassburg com Jahre 14-97 bis zum Jahre, 1872, Strassburg, 1885.

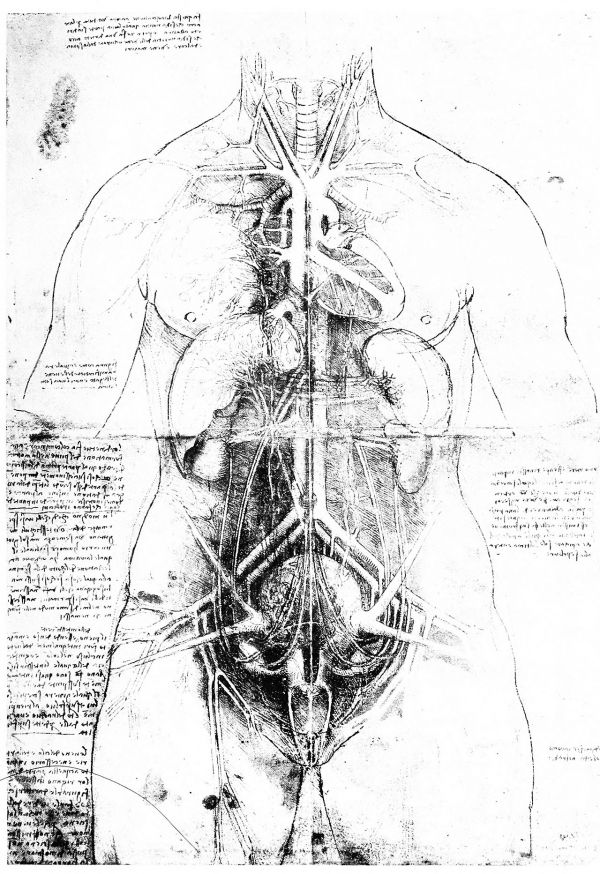

Still the figure must be recognized as a fifteenth century attempt to convey an idea of the anatomy of the human body, and it is interesting to compare with it Leonardo’s figure of the female situs viscerum (fig. 4) . This too has many inaccuracies, but they are inaccuracies due to insufficient knowledge and erroneous preconceptions and it does attempt to portray accurately the form and relations of the organs, whereas the Ketham figures evidently make no pretentions to accuracy, but are frankly conventional. It is this difference that gives Leonardo’s figures a claim to consideration. History was repeating in Science what had already taken place in Art, for just as the conventionalism of Byzantine art had given way to Giotto’s example in taking Nature itself for his model, so the overthrowal of conventionalism in fifteenth century anatomical illustration, which was consummated in the sixteenth century, was foreshadowed in Leonardo’s drawings, and this meant that in anatomy, as in other sciences, nature instead of theory was being taken as the guide. It would be idle to speculate upon what might have resulted had Leonardo’s drawings been made accessible by publication to the scientific world, but it may be truly said that he was the first to strive for accurate representation in anatomical illustration, the first to discard servile adherence to tradition and to recognize the educational and scientific value of accurate illustration. He was the pioneer in a new field that was to be more successfully exploited by his successors, notably by Vesalius andEustachius. 4

The female situs viscerum of the 1491 Ketham is taken as a type of that class of early illustrations whose purpose is medical rather than strictly anatomical; other examples would have served to demonstrate the extreme conventionalism that was characteristic of such figures in

4 The history of the anatomical illustrations of Eustachius in one respect resembles that of Leonardo’s drawings. His Tabula 1 Anatomicse were completed in 1552 and remained unpublished in the Papal Library at Rome until 1714, when, at Morgagni’s suggestion, they were published by Lancisi. They were the first anatomical illustrations to be printed from copper plates.

Fig. 4. Leonardo’s Situs figure. QI, 12.

Leonardo’s time. The 1491 Ketham has altogether six illustrations, which, with some slight modifications, are repeated in the 1493 and 1495 editions, when Mondino’s Anathomia was added to the original text. These figures are (1) a series of urine glasses arranged in a circle and illustrating the diagnostic significance of modifications of the urine as to color, precipitates, etc.; (2) a male figure showing the regions in which venesection may be satisfactorily performed; (3) the female situs viscerum ; (4) a male figure showing the wrnunds produced by various weapons; (5) a male figure upon which are indicated the regions that are the seats of various symptoms; and (6) a male figure showing the regions supposed to be under the influence of the various signs of the Zodiac. All these are traceable to earlier manuscript prototypes, just as w r as the female situs viscerum. In the Ms. Lat. 11229 of the Bibliotheque Nationale both the wound man and the symptom man have the hands upraised and the same posture is seen in the wound man of the Munich Codex German. 597, these figures, therefore, showing a relationship to the female situs figure. In later illustrations, as in the Ketham series and the wound man of Brunschwig’s Cirurgia (1497) (fig. 5), the arms are extended, but in other respects these figures show clearly their derivation from the earlier examples, the wound man being as a rule represented with the body opened so that the viscera are seen and these are of the type shown in the female figures.

The venesection and zodiac men do not, apparently, belong to the same series as the figures just considered. Sometimes the signs of the zodiac are represented on the venesection figure; sometimes there is a separate figure for them, as in the 1491 Ketham, but even here the names of the signs are inscribed in their appropriate regions on the venesection man, although a separate figure is also allotted to them. A close relationship between the two figures is to be expected, since astrological influences vrere supposed to modify the efficacy of blood letting, as well as purgation, and it was customary for the calendars of the fifteenth century to indicate days suitable for these remedial operations. 5

It is noteworthy that in none of the venesection figures are the arms upraised. Sometimes the viscera are shown, sometimes not; when they are, they are copies of those of the wound man. In the majority of the figures merely the points at which venesection may be performed are indicated, but the venesection man of Ms. Latin 11229 of the Bibliotheque Nationale shows a crude attempt at a representation of the course of the veins. This is especially interesting as it suggests a relationship between this figure and the representation of the veins in the Five-Figure Series of anatomical illustrations whose history has been most interestingly elucidated by K. Sudhoff. 5 He has discovered this series in several European manuscripts of the twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and also in Persian and Thibetan manuscripts, 7 and believes that the series may possibly be traceable to a Greek source in the later days of the Alexandrian School. These figures show an extreme conventionalism (figs. 17 and 29) but they do not call for discussion here; their interest lies in their significance as prototypes in anatomical illustration.

See K. Sudhoff, Lasstafelkunst in Drucken des 15 Jahrhundcrts, Archiv far Geschiehte der Med., vol. 1, 1908.

Fig. 5. A Wound Man. Title page of the Book of Cirurgia by Hieronymus Brunschwig (Strassburg, 1497).

The fact that Leonardo was familiar with Mondino’s Anathomia and the inclusion of that work in the later editions of Ketham’s Fasciculus render the Ketham figures especially interesting for comparison with Leonardo’s. It may be objected, however, that the comparison is hardly just, since the Ketham figures were not primarily anatomical illustrations, but were designed for medical and surgical instruction, in which, according to the standards of the time, anatomical accuracy was not considered necessary. But the Five-Figure Series was a series of anatomical illustrations and shows even a greater conventionalism than does the Ketham series. In addition to these, however, there are for comparison with Leonardo’s drawings anatomical figures dating from his time, and these deserve brief consideration. Some early prints of the skeleton may be more conveniently considered later in connection with Leonardo’s contributions to osteology, and attention may for the present be directed to the illustrations of Johann Peyligk’s Philosophies Naturalis Compendium published at Leipzig in 1499, the author being at the time Rector of the Faculty of Arts of the University. The greater part of the book is an exposition of the philosophy of Aquinas and iEgidius Romanus, but the concluding pages contain an Anothoviia totius corporis humani suorumque partium principalium, somewhat similar in scope to the Anathomia of Mondino, but briefer and based on the teachings of Aristotle, Avicenna and Constantinus Africanus. Its chief interest lies in the eleven illustrations which accompany it, the first of which, a torso showing the situs viscerum, is reproduced in figure 6. It shows a degree of conventionalism quite as extreme as that which characterizes the Ketham series, but upon somewhat different lines. The five-lobed liver, with the gall bladder resting on its surface, suggests a derivation from the Five-Figure Series, but in other respects there is little resemblance to the figures of that set.

• K. Sudhoff, Tradition und Naturbeobachtung, Studien zur Geschichte der Med., vol. 1, 1907. See also other papers by the same author in the Archiv fur Gesch. der Med., especially that entitled Abermals eine neue Handschrift der anatomischen Funfbilderserie in the third volume of the Archiv, 1910.

7 E. V. Cowdry (Anatomical Record, vol. 22, 1921) has published some early Chinese anatomical figures which are strongly suggestive of an affinity with the Five-Figure Series, but one may question this author’s belief that they may represent the originals of that series.

Fig. 6. Situs figure from Peyligk’s Philosophise Naturalis Compendium (Leipzig, 1490). After K. Sudhoff, Studien zur Geschichte der Medizin, Heft. 8, pi. 7, 1909.

The other ten figures of the Compendium are representations of individual organs, five of which, those of the stomach and intestines, the trachea and lungs, the liver, the spleen and the brain represented as seen from above in the calvarium, are identical in form with the same organs shown in the situs figure. In addition there are figures of the heart and pericardium, of the kidneys and bladder with the vense emulgentes, of the calvarium showing the sagittal and lambdoid sutures, of the brain seen from the side, similar to that of the situs figure, but showing very diagrammatically the infundibulum and hypophysis, and of the eye, curiously enough with two pupils. 8 All the figures show the same extreme conventionalism that is manifested by the situs figure. They show very little evidence of careful observation of the organs they pretend to represent, but rather suggest a derivation from some earlier source.

Two years after the publication of the first edition of Peyligk’s work, another anatomical treatise made its appearance in Leipzig. This was the Antropologium of Magnus Hundt, who had graduated in the Faculty of Arts somewhat earlier than Peyligk and had also been granted the Baccalaureate in Medicine. The Antropologium is more strictly anatomical than the Compendium and is somewhat more abundantly illustrated, ten of its eighteen figures, however, being identical with the figures of the individual organs that are found in Peyligk’s work. The situs figure (fig. 7) is different; the face looks directly forward, the brain is not shown and the tongue does not protrude. In the thorax the lungs occupy the greater part of the cavity, resting on the diaphragm, and the heart is distinctly shown; in the abdomen the stomach is given an oblique position and the kidneys and bladder are represented, but curiously displaced to the right side of the cavity. A comparison of the two situs figures strongly suggests that they were composed independently by assembling within the outlines of a torso the various organs copied from an earlier series of figures of the individual organs, a situs figure having been lacking in that series. Figures 2 to 11 of both the Compendium and the Antropologium are copied from the series, and it seems probable that some of the additional figures of the latter work were also taken from it. Figure 12 of Hundt ’s book (fig. 8) is especially interesting in this connection, since it suggests relationships with other examples of early anatomical iconography. It is not included in the Peyligk series of figures, but seems to have been from the same source as the head of that author’s situs figure. In both the face is shown in three-quarter view and in both the tongue is protruding; the significance of this protrusion of the tongue is evident in Hundt’s figure, but is altogether lost in that of Peyligk, who has greatly simplified the original figure by omitting the hair, the layers of the scalp, the cranium and meninges and using for the representation of the brain the part of the simpler figure 10 of his series that represents the ventricles.

- All these figures are reproduced in K. Sudhoff, Die Medizinische Fakultat zu Leipzig in ersten Jahrhundert der Universitat, Studien zur Gesch. der Med., vol. 8, 1909.

Fig. 7. Situs figure from the Anlropologium, de hominis dignitate of Magnus Hundt (Leipzig, 1501). After Choulant.

The arrangement of the hair in Hundt’s figure 12 recalls the coif that covers the head in some of the earlier examples of the female situs viscerum of the Ketham series, and it is noteworthy that in some of the figures of that series the tongue is shown protruded. Further the representation of the layers of the scalp, the cranium and meninges suggests that this figure or one related to it may have had some influence on Leonardo’s diagram (QV, 6v) showing the same structure (fig. 74). If so, the greater accuracy and greater artistic skill shown in Leonardo’s diagram is noteworthy. A further suggestion of the Ketham series is to be found in the posture of the venesection man of Hunclt, the left ami being flexed at the elbow, but the remaining figures of the Ilundt series do not call for special mention; they include the figure of the uterus and its adnexa, seven uterine cells or chambers being represented, a figure of the hand with chiromantic labels and three very crude diagrams of the vertebral, the sternum and the abdominal muscles.

Fig. 8. Brain and sense organs from the Antropologium of Magnus Hundt (Leipzig, 1501). After Sudhoff, Studien, Heft 8, pi. 9, 1909.

The artistic crudity of the situs figures of Peyligk and Hundt is surprising when one considers that they belong to the closing years of the fifteenth century. Hyrtl characterized them as grotesque, but the successful delineation of the grotesque demands no little artistic skill, and this these figures most conspicuously lack; Wieger’s comparison of them to caricatures drawn by small boys on walls with a lump of charcoal is more apt. So crude were they that any modifications of them could hardly fail to be an improvement, and such modifications are found in the situs figures of Gregor Reisch’s Margarita Philosophica published at Strassburg in 1503 and in that of Laurentius Phryesen’s Spiegel der Artzny, also published at Strassburg, in 1518 (fig. 9). In both of these the representations of the viscera are clearly based on those of Peyligk and Hundt, but in both also there is an attempt, slight in the Margarita figure but more successful in the Spiegel, to represent with some degree of accuracy and even with some indication of artistic ability the form of the enclosing body.

Such are the illustrations contemporary with those of Leonardo and who shall deny the surpassing excellence of the latter! They combine the appreciation of form and accurate draftsmanship of a great artist and mark the inauguration of a new period in the history of anatomy, when the anatomist and the artist were to collaborate in obtaining and recording a better knowledge of the parts of the body. The importance of this cooperation has been frequently noted, but it still requires emphasis and, indeed, one is tempted to ascribe the greater influence in the movement to the artists.

The art renaissance of the fourteenth century, whose inauguration is usually ascribed to Giotto, was the casting aside of conventionalism and the endeavor to depict Nature naturally. In ecclesiastical art, especially, the depiction of the human body played an important part and the changing modeling of the surface with changing posture incited the desire to understand more accurately the play of the muscles beneath the skin. And so the Renaissance artists of the Florentine school took advantage of opportunities to study the anatomy of the muscles in cadaveri scorticati, Pollajuolo setting the example, to be followed by his pupil Verrocchio, and Leonardo was the pupil of Verrocchio. Michel Angelo and Raphael also, as Duval (1890) has put it —

“sought for themselves in dissection the secrets of the nude and the mechanism of movement. And when, under the influence of the Italian Renaissance, the artists of other nations began to reproduce the nude in action they did it with scientific data supplied by the masters of Florence and of Rome.”

For the most part these masters approached the study of anatomy purely from the artistic standpoint; they were satisfied with the study of the skeleton or with that of the surface musculature in so far as it affected the modeling of the overlying integument. Possibly Michel Angelo went farther than this in the room and with the bodies that the prior of Santo Spirito placed at his disposal; Leonardo certainly went farther, passing from the artistic to the scientific study of anatomy.

Fig. 9. Situs figure from the Spiegel der Artzeny of Laurentius Phryesen (Strassburg, 1518).

An insatiable desire to understand Nature in all her manifestations led him far beyond mere artistic anatomy, and his genius for mechanics was stimulated by the problems presented by the action of muscles and by the flow of blood through the heart.

The Florentine artists found their opportunities for dissection in the hospitals, Leonardo in the Ospedale Santa Maria Nuova, Michel Angelo in that attached to the Chiesa di Santo Spirito. 9 But the association of artists and hospitals is not an usual one. Why should the former, even granting their desire to perfect their delineation of the human form, have been admitted to privileges usually enjoyed only by physicians? In Bologna the University through the medical faculty gave opportunities in public and private Anatomies for the acquisition of some knowledge of the human frame. But in Florence, during the greater part of Leonardo’s residence in that city, there was no university. Earlier efforts had been made looking forward to the establishment of a Studium Generale, and as far back as 1320 the “excellens sapiens et expert us vir, magister Bartholomeus da Varignana” was engaged by the city to teach the art of medicine. 10 In 1348, the year of the Great Plague, a serious attempt was made to establish a Studium Generale including instruction in civil and canon law, medicine, philosophy and the other sciences and the plan received the approval of Pope Clement VI. But the institution maintained but a precarious existence, notwithstanding the granting of an imperial charter in 1364 by Charles IV, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, and notwithstanding the appointment in 1373 of Boccaccio as lecturer on Dante. And so it lingered on, unable even with the support of the Medici to compete with the other Italian universities, and eventually in 1472, two years after Leonardo had taken up his residence in the city, the Signoria decided that Florence was not a suitable place for a Studium Generale and ordered its removal to Pisa.

While the University remained in Florence, provision was made by the Statutes for the dissection of two cadavers each year, and

‘‘In case God grants the Studium to grow, then let the Podesta see to the delivery of not two but three bodies of alien criminals each year; whatever their foul felonies be, let them be hanged (not burned as is the wont with witches, nor beheaded) and delivered the same day, for corruption comes on apace.” (Streeter, 1916.)

Thus dissection became a recognized procedure in Florence and one may suppose that even after the removal of the University, the city authorities and those in charge of the hospitals might be willing to countenance it if there were requests for it from responsible persons.

• A. Condivi, Vila di Michelangelo, Pisa, 1823. Quoted by G. Martinotti, L’insegnamento dclianatomia in Bologna prima del Sccolo XIX, Bologna, 1911.

10 P. II. Denifle, Die Univcrsilalcn dcs Miltclallers bis H00, Berlin, 1885.

Indeed it was during Leonardo’s lifetime that Antonio Benivieni, a Florentine, wrote his treatise De abditis nonnullis ac mirandis morborum et sanationum causis, a work that has the distinction of being the first special treatise on pathological anatomy. Benivieni was one of three brothers, each of whom gained recognition as an author — Girolamo as a poet, Domenico in theology and Antonio in surgery and anatomy. Of Antonio’s life little is known except that he died in 1502, his treatise being published in Florence after his death by his brother, the theologian. It is a record of a number of abnormalities and pathological conditions observed in autopsies, of which, he states, he performed no less than twenty, without counting a number that were made privatim, and he gives further evidence of the freedom with which autopsies were then permitted in Florence by considering it worthy of remark that only once was a private autopsy denied him.

But there was another factor in Florentine life that conduced to the recognition of artists as suitable persons to whom the privilege of dissection might be granted. During the Middle Ages the system of Trade Guilds played an important part in the life of the Italian cities and in none more than in Florence. Holding an important place among these Guilds was that of the Apothecaries and Doctors, of which records are in existence dating back as far as the twelfth century. 11 The Guild was under the guidance of four consuls, elected annually from the members and having almost unlimited jurisdiction over all apothecaries, physicians, surgeons, midwives, herbalists, distillers and undertakers, and to these were also added the booksellers, the silk mercers and the artists. The last named placed themselves under the protection of the Guild in 1297, “being beholden for their supplies of pigments to the apothecaries and their agents in foreign lands,” but it was not until 1339 that they became a regular corporation under the Guild. Luca della Robbia was several times elected consul and the escutcheon of the Guild, the Virgin and Child in chief supported by pots of annunciation lilies, executed by him, was formerly on the facade of the Palazzo de’ Lamberti, the residence of the consuls of the Guild.

The artists were thus brought into intimate business and political relations with the physicians and surgeons, fellow craftsmen as it were, and the privilege of dissection accorded the latter may readily have been extended to the artists. Leonardo was enrolled in the Compagnia de’ Pittori in 1472, and it is certain that he performed dissections in at least one hospital in Florence.

11 E. Staley, The Guilds of Florence, London, 1906.

The effect of what Ruskin has stigmatized as the “science of the sepulchre” on the future development of Art need not concern us here, but that of the intrusion of the artists into the field of anatomy may be considered. Leonardo’s anatomical drawings were not, it is true, given to the public until quite recently, but they must have been known to the wide circle of his friends and acquaintances and their contrast with contemporary anatomical illustrations must have opened the eyes of physicians to the possibilities for improvement. But whether or not Leonardo’s example had anything to do with it, improvement began to show itself shortly after his death. Rosso, also a Florentine artist, who, like Leonardo, took up his residence in France, under the patronage of the then King, Francis I, undertook to prepare for his royal patron a series of anatomical illustrations, which remained incomplete owing to the artist’s death in 1541. Only one plate remains, a copperplate reproduction by Domenico Florentino, a pupil of Rosso, who accompanied him to France. It has been reproduced by Choulant (1852) and shows front and back views of a skeleton and of an uomo scorticato, the figures being posed and provided with a background of drapery and various pieces of armour. The figures are not up to the standard set by Leonardo at his best, either in drawing or in accuracy, but they are attempts by an artist to represent the structure of the human frame as it really is, quite free from the conventionalism of the past. They belong to the new era of anatomy inaugurated by Leonardo.

The same may be said of the illustrations of the Musculorum humani corporis picturata dissectio by Gianbattista Canano, Professor of Anatomy at Ferrara, published probably in 1541. 12 Canano, at the instigation of his friend Bartolommeo Nigrisoli, undertook to publish naturetrue representations of the muscles of the body and, doubtful of his own draftmanship, enlisted the services of an artist, Girolamo da Carpi, a pupil of Garofalo, to draw the muscles from his dissections. Only the first part, dealing with the muscles of the arm, was published, for Canano, learning of the excellent illustrations that Vesalius had had prepared for his great work De corporis humani fabricd, suppressed the remaining parts. The illustrations are plain, simple representations of the parts as seen by the artist, without any artistic embellishments, but fine as they are they failed to achieve the excellence of those of Vesalius.

Canano employed an artist and so did Vesalius, and the latter’s artist, Stephen von Calcar, was allowed greater artistic freedom, for many of his figures were posed and have sections of a landscape for a background, just as have the Mona Lisa and the Vi&rge des Rochers. These additions make manifest the artist’s part in the improvement of anatomical illustration. Sometimes, indeed, the artist was allowed to run riot and entirely dominate the picture, as in Charles Estienne’s De dissedione partium corporis humani illustrated by Etienne Riviere. 11

15 G. Canano, Musculorum humani corporis picturata dissectio (Ferrara 1541?). Facsimile edition annotated by Harvey Cushing and Edward C. Streeter, Florence, 1925.

13 This work was not published in its entirety until 1545, but the preparation of the illustrations began long before that date, some of the plates being dated 1530, 1531 and 1532.

Here full-length figures are represented even when a single organ is the raison d’etre of the illustration, and to this is added a superabundance of architectural accessories, upholstering and drapery, until the essential of the picture becomes an insignificant part of it.

Accurate portrayal demands accurate observation, and it was the artists who led the way to the betterment of anatomical illustration. The anatomists were not slow in perceiving the advantages of accurate representations of their dissections, but all anatomists were not skilful draftsmen, nor were all artists, like Leonardo, skilled anatomists. And so collaboration resulted. Nor was the improvement confined to the illustrations; more accurate delineation led to more detailed description and this to greater care and thoroughness in dissection. The earlier conventionalized descriptions and illustrations were discarded, and with the publication in 1543 of Vesalius’ great work, the De humani corporis fabrica, the science of Descriptive Anatomy assumed its modern form and scope.

How great Leonardo’s influence in this movement may have been remains uncertain. Perhaps too much importance has been attached to the facts that his anatomical studies were not given publication and that later anatomists did not refer to them. But the artists of his time or slightly later, such as Vasari and Benvenuto Cellini, certainly knew of them and it hardly seems possible that they should have remained unknown to those who worked with him in Verrocchio’s atelier, Botticelli, Perugino and Lorenzo di Credi, and to his pupils, Bernardo Luini and Ambrogio Preda. Of anatomists who may have been influenced by him only Marc Antonio della Torre of Pavia may be named, but the close association of the artists and physicians in the Guild of Apothecaries suggests that the latter may probably have had knowledge of them. True no mention of his name is to be found in the works of either Canano or Vesalius, but reference toother authors had not become the mode in those days, and, as Roth (1905) has pointed out, while Vesalius does not mention by name Berengario, Dryander, Guintherius and Sylvius, yet references to their w r orks are readily recognizable. If, as has been suggested above, the impulse to the new movement in anatomy came from the artists, Leonardo may well be recognized as its originator and Vesalius as its great protagonist.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Reference: McMurrich JP. Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist. (1930) Carnegie institution of Washington, Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore.

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 18) Embryology Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 4. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Leonardo_da_Vinci_-_the_anatomist_(1930)_4

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G