Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 2: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "CHAPTER III POSSIBLE LITERARY SOURCES OF LEONARDO’S ANATOMICAL KNOWLEDGE[edit] In studying Leonardo’s manuscripts, one notes from time to time a drawing or sketch showing...") |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{McMurrich1930 header}} | |||

=Leonardo da Vinci - The Anatomist= | |||

==Chapter II Anatomy from Galen to Leonardo== | |||

Since, then, a just estimate of Leonardo’s contribution to anatomy can only be arrived at when the state of that science in his day is understood, it will be advisable to consider the opportunities for anatomical studies available during the Middle Ages, the methods employed and the results. | |||

With the death of Galen at the end of the second century of our era, the study of Anatomy entered upon its dark days and for nearly thirteen centuries scarcely a single fact was added to the knowledge of the structure of the human body. Nor does this statement, strong as it is, sufficiently express the condition of anatomical knowledge during this long period; not only was there no progress, there was retrogression. Throughout the Byzantine period synopses of Galen satisfied all demands, the most celebrated being the Collecta medicinalia of Oribasius, compiled at the request of the Emperor Julian and setting forth in concise and orderly succession the statements of the garrulous Galen. Theophilus Protospatharius in the seventh century does seem to have interested himself in dissection and to have added slightly to anatomical knowledge, but such activity was exceptional; and while the period produced some works of importance in the history of medicine and surgery, as far as anatomy was concerned it was almost barren. Later, in Europe the feudalism of the Middle Ages suppressed personal initiative among the mass of the people, each man’s actions and behavior being dictated by the behests of his feudal lord; and among the clerics, from whom light might have been expected, the dogmas of the Church, formluated by the great Councils of the fifth and sixth centuries, defined within narrow limits the mode of thought. Life in all its aspects became highly conventionalized; feudalism produced such conventionalisms as knight-errantry, trial by combat, courts of love and, the climax of them all, the science of Heraldry; philosophy became conventionalized into rhetorical contests between Realists and Nominalists; and art, employed almost exclusively for religious instruction, became stereotyped into the stiff expressionless forms characteristic of early Christian paintings. | |||

Conventionalism is dogmatism crystallized, and dogmatism means finality. What wonder then that the formulation of Christian theology, with its attendant sectarian bitterness, persecutions, riots, and even massacres, resulted in a belief that the last word had been spoken on matters theological. The essence of that theology was absolute faith in the dogmas of the Church ; faith and not reason was the foundation of knowledge of both the supernatural and natural worlds, and of the two worlds it was the supernatural that held the chief place in men’s minds. For their knowledge of natural phenomena they were content to rely upon the statements contained in the writings of the Fathers, these statements in turn being based upon those of earlier writers, provided that these did not conflict with the patristic interpretation of the Scriptures. The character of mediaeval philosophy has been aptly stated in these words: | |||

“A reversed pyramid, whose base was occupied by spiritual matters and of which the imperceptible point of the apex was constituted by man and nature, as things transitory and fleeting — that is the symbol of mediaeval doctrine.” (Solmi, 1910.) | |||

Under such circumstances there was naturally no incitement to personal observation, and experiment and science languished. It became conventionalized largely according to the Galenic tradition, and this tradition came to possess a finality; it was complete and unassailable, there was nothing to be added to it and nothing to be corrected. The word tradition is used advisedly because during the middle ages the original Galen had become practically unknown. Except in Constantinople and probably in such centers as Salerno and Montpellier, Greek had become to all intents a dead language, and Hippocrates, Aristotle and Galen were known only through tradition that had filtered down from the past. Fortunately the works of these authors were not destined for oblivion; they were saved to the World and restored to Europe through the appreciation by the Arabs of what was best in the philosophy and science of the Greeks. | |||

The role of the Arabs in the history of the intellectual development of Europe was an interesting one. Primarily a pastoral and more or or less nomadic people, divided by intertribal feuds, they were welded into a nation by the religious enthusiasm of Mahomet and his small band of early converts, and, after a remarkable career of conquest, they settled down in their capitals to cultivate the arts of peace, just as the Ptolemies had done centuries before in Alexandria. Bagdad and Cordova became centers of learning in which Arabian sages studied and expounded the wisdom of the Greeks. But the Arabs had no knowledge of the Greek tongue and their first care was to secure the services of Syrians, Jews and Nestorian Christians to translate into Arabic the works whose contents they desired to master, and it was not long before all the important scientific and philosophical treatises of classical times appeared in an Arabic guise. From these translations as a source, there flowed a stream of abstracts, commentaries and treatises by Arabian authors, which, however, added little to the volume of human knowledge. For the Arabs showed little originality; what they handed on was Greek science and philosophy with, it is true, some oriental color in its presentation and application, but still essentially Greek. The Arabs contributed little, but they were the keepers of the Light through the Dark Ages and they restored it to the Western world where it had become well-nigh extinct. | |||

The activities of the Arabian commentators could not indefinitely remain unknown to the scholars of western Europe. Already in the latter half of the eleventh century Constantinus Africanus, after spending forty years of his life among the Arabs, was received into the Monastery of Monte Cassino, not far from Salerno, and interested himself in the translation into Latin of Arabic versions of Galen’s Ars parva and Hippocrates’ Aphorisms, as well as of treatises by Ali Abbas and other Arabian commentators of less renown. The capture of Toledo from the Moors by Alfonso VI in 1085 also revealed to the Christian conquerors something of the wealth of the Arabic literature and awakened desire for a better acquaintance with the wisdom of the Arabs. But it was in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries that Arabian influence became most pronounced in Europe. In the twelfth century Toledo became the seat of a bureau of translation organized by the Archbishop Raymond and in the thirteenth century the capture by the Christians of such cities as Cordova and Seville brought further treasures into the hands of the conquerors. Especially under Alfonso X, surnamed The Wise, earnest attempts were made to utilize these treasures to the full; the observations of the Arabian astronomers were collated to form the Alfonsine Tables, while the work of translation went on apace. | |||

of the | But not only were the conditions in Spain favorable for the dissemination of Arabian learning, circumstances made Italy at this same time especially ready for its reception. The Hohenstaufen rulers of Sicily and Naples were strongly biased in favor of the eastern customs and their courts were oriental rather than occidental in their ceremonials. This was especially true in the case of Frederick II, who, notwithstanding that he was under the ban of the Church, led a crusade to the Holy Land and gained important concessions from the Sultan of Jerusalem, with whom he swore a blood-brotherhood. In 1241, Frederick promulgated an edict setting forth the requirements necessary for a license to practice medicine and surgery within his dominions, these requirements demanding that the candidate should have studied the science of logic for at least three years and thereafter should have pursued the study of medicine for five years and have practiced for one year under the guidance of a reputable physician, after which he must satisfy the masters at Salerno of his fitness by satisfactorily undergoing a public examination chiefly on the works of Hippocrates, Galen and Avicenna. It is evident that at this time Arabistic medicine was thoroughly established at Salerno, then at the height of its renown as a center for medical training, but soon to give place to the younger universities of Montpellier and Bologna. | ||

In these, too, Arabian influences became predominant in the thirteenth century. Arnald de Villanova, probably a Spaniard and familiar with both Greek and Arabic, came to Montpellier toward the end of the century, and by his learning, originality and independence contributed greatly to the overthrow of the scholastic methods and to the substitution therefor of the forgotten precepts of the ancient masters, preserved and elaborated by Rhazes and Avicenna. Indeed, he was more than an Arabist; like his contemporary Roger Bacon he advocated and practised observation and experiment as the sources of scientific knowledge, thereby gaining for himself, as did Bacon, reputation as an exponent of the Black Art. His alchemistic predilections did not, however, lead him into mysticism, and his skill as a physician gave an authority to his appreciation of the Arabian contributions to medicine and found a reflection in the compendiums and commentaries of Arabian medical writers that came from representatives of the Montpellier school during the fourteenth century. | |||

The | The University of Bologna primarily possessed but two faculties, those of Arts and Law, each with its own rector, and although it seems probable that medicine was taught there as early as the eleventh century, it was not until 1260 that the teaching of Thaddeus Alderotti, commonly known as Thaddeus Florentinus, began to attract students in considerable number, and in 1306 the Medical faculty was given an independent rector. Thaddeus was well versed in the medical lore of his day, both Greek and Arabic, and he and his pupils added to the list of commentaries on the works of the ancient and more recent writers. Of these works those chiefly studied by the students were, as at Salerno, the Ars parva of Galen and the Aphorisms of Hippocrates, but acquaintance w r as also required with other works of those authors and with the Colliget of Averrhoes, the Canon of Avicenna and the Almansor of Rhazes. (Rashdall.) | ||

In the thirteenth century, accordingly, the three great medical schools of Europe were deeply under the influence of Arabian authors, and while these restored a better knowledge of the Greeks, they also imposed limitations, since that knowledge came bound by the restrictions imposed by Arab custom. Chief among the results of these restrictions was the divorce of medicine and surgery, which was so pronounced during the Middle Ages. It was due in part to the influence of the oriental tradition against the use of the knife and in part to the general attitude inculcated by Scholasticism. Medicine lent itself more readily to the dialectic dear to the Scholastic, to argumentation as to causes, principles and treatment; whereas surgery required prompt and effective action, and in the foundation of the Universities it was medicine that was taught and practised by the Faculties of Medicine, and surgery was largely left in the hands of barbers, bathkeepers and even public executioners. There were, it is true, some learned surgeons, such as Theodoric and William of Saliceto of Bologna, Lanfranchi and de Monde ville of Paris and Guy de Chauliac of Montpellier, but their number was small and for the most part the physician deemed it beneath his dignity to undertake the treatment of wounds or fractures or operations such as couching and lithotomy, to say nothing of bleeding and tooth extraction. For the physician an intimate knowledge of anatomy was unnecessary; if he knew the position of the various organs of the body and their presumed functions he had all he required, and this he could obtain from a translation of an Arabic summary of Galen’s anatomical treatises, such as is found in Avicenna’s Canon. Ihe original treatises, and especially the de administrationibus anatomicis, remained neglected, even though an Arabic translation of the latter had been made by Honein (Johannitius) or his son-in-law Ilobeisch as early as the ninth century. It was translations of Arabic versions of the Ars medica (commonly known to the Arabists as the Microtechne) and the Methodus medendi {Megalechne) that were especially studied during the Middle Ages: and while the de usu partium awakened some interest for Galen’s anatomical treatises, the summation of the anatomical knowledge of his day, the learned physician felt no need and the barber-surgeon was too ignorant to make use of them. | |||

So the study of anatomy became conventionalized into the reading of a translation into Latin of an imperfect summary by an Arab of Galen’s teaching, and, since its source was Galen, the complete submission to the dictates of antiquity that characterized the Middle Ages gave it an authority and finality that well-nigh suppressed all stimulus to further inquiry. Indeed, ignorance of the original treatises concealed the fact that Galen’s contributions to anatomy were based on the dissection of animals, chiefly monkeys, that his anatomy was not in reality human anatomy, and when this fact was revealed by the investigations of Vesaiius in the sixteenth century their unshaken confidence in the infallibility of Galen led at least one of the Galenists to the conclusion that the structure of the human body mast have altered materially in some respects during the centuries that had elapsed since Galen’s day. | |||

But notwithstanding the profound subservience to dogma, the faint flicker of revolt against it shown by such men as Roger Bacon and Arnald de Yillanova was not entirely extinguished, for the thirteenth century witnessed the encouragement of the study of anatomy by direct observation, such as had not been given since the days of Galen. The Emperor Frederick II, when prescribing the course of study to be pursued by those wishing to practice medicine within his dominions, enacted that no surgeon should be allowed to practise unless “Above all he has learned the anatomy of the human body at the medical school and is fully equipped in this department of medicine, without which neither operations of any kind can be undertaken with success, nor fractures be properly treated.” 1 This does not necessarily mean that the prospective surgeon must have learned his anatomy by the actual dissection of a human body; the School of Salerno was indeed noted for its interest in practical instruction in medicine, but there is no record of a dissection of a human body having been performed under its auspices. Toward the close of the eleventh century, at the period when Arabic influences were beginning to supplant the Greek tradition that had persisted in the School, one Copho, a member of that school, wrote a brief treatise on the anatomy of the pig, Anatomia porci , 2 consisting in its printed form of about two and a half pages and amounting to little more than an enumeration of the various organs to be seen in opening the body of the animal. It describes an autopsy rather than a dissection, but is of interest as evidencing some appreciation of the importance of a knowledge of anatomy based on personal observation. Somewhat more detailed was the Demonstratio anatomica by an anonymous author of the same school, also based on the autopsy of a pig, but these early attempts of the Salernitans to revive the practical study of anatomy were destined to be supplanted by treatises based on the study of the human body, the first attempts in this direction of which there is record, since the days of the Alexandrian anatomists. | |||

It is to Bologna that the credit for the revival of practical human anatomy is due, and it is interesting to note that the long-continued repugnance to the dissection of human cadavers was only gradually overcome by the desire for a more definite knowledge of the pathological changes produced by disease or by the demands of justice for definite evidence in cases of suspected poisoning. The first instance on record of such a revival was a legal autopsy performed by the Bolognese surgeon William of Saliceto on the body of the nephew of the Marchese Uberto Pallavicino, who was suspected of having died from the administration of poison. William of Saliceto was the author of a Cyrurgia, written in 1275, the fourth book of which is devoted to a compendium of Anatomy in five chapters. It is Galenic anatomy, similar to that found in mediaeval manuscripts, and, to judge from the use of Arabic terms for certain parts, was based upon an Arabic source, probably Avicenna. That William, “qui Gulielmina dicitur,” | |||

1 J. J. Walsh, Mediaeval Medicine, London, 1920. The translation is made from a copy of the edict published in Huillard-Brehollis’ Diplomatic History of Frederick II, with Documents, Paris, 1851-1861. | |||

2 A translation of this and also of the Demonstratio mentioned below will be found in G. W. Corner, Anatomical Texts of the Earlier Middle Ages. Carnegie Inst. Wash., 1927. | |||

had practical experience in dissection is indicated by the directions he gives as to how the incisions should be made for the exposure of various parts and by his statement that a certain duct, wrongly described by his source as existing, was unknown to him. | |||

A few years later (12S6) a Parmesan or Lombard physician is reported to have made autopsies of the bodies of persons who had died of an aposthematous pestilence (Solmi, 190G) and in 1302 a postmortem examination was ordered of the body of one Azzolino, who was suspected of having been poisoned. The examination was made by Bartholomeo da Varignana, a famous teacher and practitioner in Bologna, with four associates, and these reported — | |||

“quod dictum Azzolinum ex veneno aliquo mortuum non fnisse, sed potius et certius ex multitudine sanguinis aggregati circa venam magnam qua? dicitur vena chilis, et venas epatis propinquas eidem, unde prohibita fuit spiritus per ipsam in totum corporis effluxio, et facta caloris innati in toto mortificatio, seu extinctio, ex quo post mortem celeriter circa totum corpus denigratio facta est, quam paxionem adesse prrcdicto Azzolino praedicti Medici sensibiliter cognoverunt visceribus ejus anathomice circumspectis.” 3 | |||

The recognition of autopsies given by the authorities in this case was no doubt an important factor in bringing about a greater freedom in the investigation of human cadavers, and it seems probable that early in the fourteenth century advantage was taken of this freedom for the performance of autopsies at Bologna as a means of anatomical instruction. In 1316 there appeared a text-book of anatomy from the pen of Mondino di Luzzi which was destined to supplant that portion of the first book of Avicenna’s Canon which treated of anatomy. 4 It remained the favorite anatomical text-book for over two centuries, partly because of its directness and simplicity of statement, partly because of its recognition of the practical application of anatomy and partly, and largely, because in the treatment of the subject it followed the order in which the various organs would be exposed in an autopsy. In other words it was a Manual of Practical Anatomy rather than a systematic treatise of the subject. It bears evidence in its arrangement that its author is treating his subject on the basis of personal practical experience and, indeed, in the text there is a statement that in 1315 he performed autopsies on two female subjects; but nevertheless the work makes no contribution to the more accurate knowledge of anatomy; it gives nothing beyond what was contained in the Arabian treatises; it repeats their errors and shows their influence in the use of Arabic terms for many of the organs. The contents of Mondino’s work will later be considered more in detail, since it was one of the sources of Leonardo’s knowledge of anatomy; its present significance is that it indicates an increasing interest in the practical study of the human body and it probably had influence in further promoting that interest. | |||

3 M. Medici, Compendia Slorico della Scuola Anatomica di Bologna, Bologna, 1857. | |||

4 See G. Martinotti, L'insegnamcnto dell’ Anatomia in Bologna prima del secolo XIX, Bologna, 1911, page 61, where is quoted a portion of a statute of the University of 1405 in which, in the prescription of texts to be studied in the successive years of the medical course, the first book of Avicenna is mentioned always with the addition of the words “excepta anathomica.” | |||

After Mondino’s time the dissection of human cadavers for the purpose of instruction became of frequent occurrence. Guido de Vigevano, who was physician to the French King Philippe de Valois, in the concluding chapter of his Liber notabilium, which consists mainly of excerpts from translations of Galen and was written in 1345, endeavors to demonstrate the structure of the human body by a series of eighteen figures, which he believes himself capable of doing “cum pluribus et pluribus vicibus ipsam (anathomiam) feci in corpore humano.” 6 Similarly Guy de Chauliac, the greatest of the surgeons of Montpellier, states in his Grande Chirurgie that his Bolognese teacher, Bertucci, who died of the Black Plague in 1347, performed many Anatomies, each consisting of four lessons, as follows: | |||

“In the first he considered the nutritive organs because they perished soonest, in the second the spiritual organs, in the third the animal organs, and in the fourth the extremities .” 6 | |||

Nor was the performance of Anatomies or autopsies limited to Bologna. Gentilis da Foligno, who for a time taught at Bologna and at Perugia and who like Bertucci, fell a victim to the Black Plague, is recorded as having performed an autopsy at Padua in 1341, in which he discovered in the gall bladder of the subject “a green stone,” 7 and further it is also on record that the anatomists of Perugia, when making an anatomy in 1348, found in the neighborhood of the heart a small sac full of poison, the subject having died of an epidemic (Solmi, 1906). | |||

The performance of Anatomies was not, however, allowed to proceed without let or hindrance. Even in Mondino’s time there is record (1319) of a trial in Bologna of four Masters who were accused of having disinterred the body of an executed criminal and of having transported it to the house in which a certain Master Albertus of Bologna was accustomed to lecture, a witness testifying that there he had seen Master Alberto with four other Masters and others persons — | |||

“existentes super dictum corpus cum rasuris et cultellis et aliis artificiis et sparantes dictum hominem mortuum et alia facientes qute spectat ad artem medicorum .” 8 | |||

8 E. Wickersheimer, L“Anatomie” de Guido de Vigevano, medecin de la reine Jeanne de Bourgogne (1345), Arch. f. Gesch. derMedizin, vol. 7, 1913. | |||

6 Guy de Chauliac, La Grande Chirurgie, restituee 'par M. Laurens Joubert, Rouen, 1632. This is one of the many printed editions of this famous work, which was originally written in 1363. | |||

7 M. Roth, Andreas Vesalius, Bruxellensis, Berlin, 1892. | |||

8 See M. Medici, loc. cit. p. 12. | |||

In France, or at least in Paris, it would seem that in the fourteenth century the dissection of the human body was prohibited by the clerical authorities except under a special privilege, concurrent evidence to that effect being furnished by Henri de Mondeville and Guido de Vigevano. De Mondeville was by birth a Frenchman, but he was probably educated in Italy, although there is no direct evidence in support of this idea. At all events he was at Montpellier in 1304 and demonstrated anatomy there, or rather, as Guy de Chauliac informs us, he “pretended to demonstrate anatomy” by the use of thirteen figures. Thence he passed to Paris where he became surgeon to Philippe le Bel, to whom he dedicated his Chirurgie, begun in 1306 but never completed. In the first part of this he treats Anatomy, essentially on the basis of Avicenna’s teaching, but with indications of the methods to be pursued in demonstrating it and in this connection he states — | |||

“Si debeant (corpora) servari ultra 4 noctes aut circa et exinde a Romana Ecclesia speciale privilegium habeatur, findatur paries ventris anterior a medio pectoris usque ad pectinem. . . ” 3 | |||

Guido de Vigevano, whose early training was presumably obtained in Italy, also based his teaching on figures, making these, indeed, the essential part of his chapter on anatomy, giving as his reason for so doing “Quia prohibitum est ab Ecclesia facere anothomiam in corpore humano.” 10 It is noteworthy that both these works were written in Paris at a time when autopsies were being freely performed in Italy, a fact which suggests that the prohibition may have been a local one. No general enactment of the Church on the question of Anatomies is known, but it has been held that the Bull of Boniface VIII De Sepulturis, issued in 1300, had a prohibitory effect on the practical study of anatomy. The Bull had, however, quite another purpose as is shown by its title which may be translated thus: | |||

“Those eviscerating the bodies of the dead and barbarously boiling them in order that the bones, separated from the flesh, may be carried for sepulture into their own country are by the act excommunicated.” 11 | |||

It was called forth by a practice that had arisen during the Crusades, and while it is possible that it was interpreted by the Parisian clergy as setting a ban on Anatomies, no such interpretation, apparently, was placed upon it in Italy, or if it was, it was short lived. Indeed Alessandro Benedetti, a contemporary of Leonardo, states in his Historia corporis humani (1497) that anatomists were even in the habit of preparing skeletons by boiling without fear of excommunication. | |||

9 J. L. Pagel, Die Chirurgie des Henri de Mondeville , Berlin, 1892. | |||

10 E. Wickersheimcr, loc. cit., p. 13. | |||

11 The Bull is quoted in its entirety in a paper by J. J. Walsh, The Popes and the Ilistonj of Anatomt/, Medical Library and Historical Journal, vol. 1, 1904. See also Mediaeval Medicine, London, 1920, by the same author. | |||

The Humanistic movement, born in Italy in the fourteenth century, manifested itself primarily in literary studies, but soon expanded to include other fields of intellectual activity. Underneath the literary movement and bearing it along was the awakening spirit of the Renaissance, the yearning for emancipation from the domination of dogma, the dissatisfaction with knowledge acquired at second hand, the desire to learn and know from personal observation. This manifested itself in an increasing demand for opportunities for Anatomies, sufficiently insistent to compel from the authorities enactments providing a definite supply of cadavers to be used for such purposes. The first of these enactments of which there is record was passed by the Great Council of Venice in 1368, decreeing that an Anatomy should be made once in each year before the physicians and surgeons, the dissections, according to Nardo, 12 being performed in the Hospital of Ss. Peter and Paul. Shortly after, probably in 1376, a similar privilege was granted to the Medical faculty of the University of Montpellier, this privilege being confirmed several times in later years up to the close of the fifteenth century. | |||

It was in that century, however, that the granting of such a privilege became generally established in Italy, indicating a widespread interest in the study of Anatomy. It has been shown that early in the fourteenth century autopsies and Anatomies had been conducted with some frequency at Bologna, but no records have yet been found of decrees legalizing the practise in that municipality. In the early days of the Universities, the relations between the students and teachers were more intimate than in later days. The Italian Universities w T ere primarily guilds of students as contrasted with the guilds of Masters of which the University of Paris was the prototype:’ 3 the students selected their own Masters, the instruction they received was according to personal arrangements into which they entered with their Masters and much of the teaching was done in the houses of the Masters. Martinotti 14 has shown that even anatomy was taught in this extra-mural fashion and continued to be taught privately long after the institution of Public Anatomies, even, indeed, until Galvani’s time, at the close of the eighteenth century, and later. The responsibility for the supply of subjects for these private Anatomies appears in the early days to have rested with the students, an arrangement that naturally led to disturbances and conflicts, to obviate which the Statutes of the University of 1405 prescribed that no one, doctor or student, should be allowed to have possession of a body, unless he should previously have obtained a license for that purpose from the Rector. But this plan, apparently, was not quite satisfactory, and in 1442 it was modified by requiring the Podesta of Bologna to furnish each year at the request of the Rector, two cadavers upon which Anatomies might be made, a condition being made, however, that the cadavers must be obtained from places not less than thirty miles distant from the city of Bologna. This limitation was removed in 1561, after which date the bodies of persons who had been resident even in the suburbs of Bologna might be taken, “modo cives honesti non sint et superioribus ea dare placeat.” | |||

12 Quoted by Bottazzi (1907). | |||

13 H. Rashdall, The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages, Oxford, 1895. | |||

14 G. Martinotti, loc. cit., p. 12. | |||

Nor was Bologna the only Italian city in which the practical study of anatomy was zealously conducted during the fifteenth century, indeed, the renown of Padua as a center for medical instruction was almost, if not quite, as great as that of the sister university. The charter of the University of Padua was granted by the Emperor Frederick II in 1222, and it is probable that it undertook instruction in medicine from its foundation. It is also probable that Anatomies were conducted there even in the fourteenth century, for it was a professor from Padua who performed the first Anatomy in Vienna in 1404. At the beginning of the fifteenth century Padua fell under the domination of Venice (1405) and after that date it quickly rose to great prominence as an anatomical center. Autopsies are on record as having been performed in 1420 and again in 1430, and Montagnana in his Consilia, written in 1444 while he held a professorship of medicine at. Padua, states that he had witnessed fourteen Anatomies. There is record of a public Anatomy held in 1465 at which the doctors discussed all the doubtful points concerning the structure of the body, “atque tandem corpus cum maxima festivitate humatum.” It was not until 1495, however, that a statute was passed requiring the annual delivery to the University for anatomical purposes of two bodies, one male and one female.’ 5 A similar regulation was in force in the fifteenth century at Siena, Perugia, Genoa and Ferrara, and in 1501 at Pisa, while it is known that early in the sixteenth century dissections were made at Pavia by Marc Antonio della Torre. | |||

It is evident from these data that in the time of Leonardo, the latter half of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century, the dissection of the human body was a well-recognized feature of medical instruction; the long-standing prohibition of it, imposed partly by general sentiment and partly by religious opinion, had given way to the spirit of the Renaissance. It will be of interest later to consider the conditions obtaining at Florence, where Leonardo entered upon his anatomical studies, but here a brief account of the methods adopted in the performance of an anatomy will not be amiss, since it will explain the failure of the early anatomists of the Renaissance to advance in their knowledge of anatomy and the greater success of Leonardo. | |||

16 M. Roth, Andreas Vesalius, Bruxcllcnsis, Berlin, 1892. | |||

Why was it that with all their opportunities for direct observation, the anatomists of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries added little or nothing to the scanty and superficial description of the human body contained in the Canon of Avicenna? Why did they fail even to reach the standard of exposition set up by Avicenna? Because, in the first place, Avicenna was epitomizing the anatomy of Galen while the more modern writers were either epitomizing Avicenna’s epitome, not yet having access to the original Galenic treatises, or else, as in the case of Mondino, were describing on the basis of Avicenna’s epitome what could be seen in an Anatomy, and their Anatomies were limited in their duration, since they possessed no means of preserving the bodies from putrefaction, and in the warm climate of Italy the work could not be prolonged over more than three or four days. Nor was it carried on without intermission during the available time, but apparently was divided into usually four demonstrations in the manner described by Bertucci (see p. 13) ; and furthermore the time available for observation was frequently greatly curtailed by prolonged discussion by the Masters present, of moot points suggested by the demonstration. With these limitations of time it is evident that in the Anatomies of the fifteenth century only a superficial examination of the more conspicuous organs of the body could be made; of detailed dissection there was none. Mondino excuses himself for omitting a discussion of the “simple parts” because these were not perfectly apparent in dissected bodies, but could only be demonstrated in those that had been macerated in running water. He was also accustomed to omit consideration of the bones at the base of the skull, because these were not evident unless they had been boiled, and to do this was to sin, and, similarly, he omitted the nerves which issue from the spinal column, because they could be demonstrated only on boiled or thoroughly dried bodies and for such preparations he had no liking. So too Guy de Chauliac and Berengarius da Carpi maintained that the muscles, nerves, blood-vessels, ligaments and joints could only be studied in bodies that had been macerated in flowing or boiling water or else thoroughly dried in the sun, and there is no evidence that such preparations were demonstrated at the Anatomies. These were little more than demonstrations of the organs contained in the three ventres of the body, the abdomen with the membra naturalia ; the thorax with the membra spiritualia and the head with the membra animalia. | |||

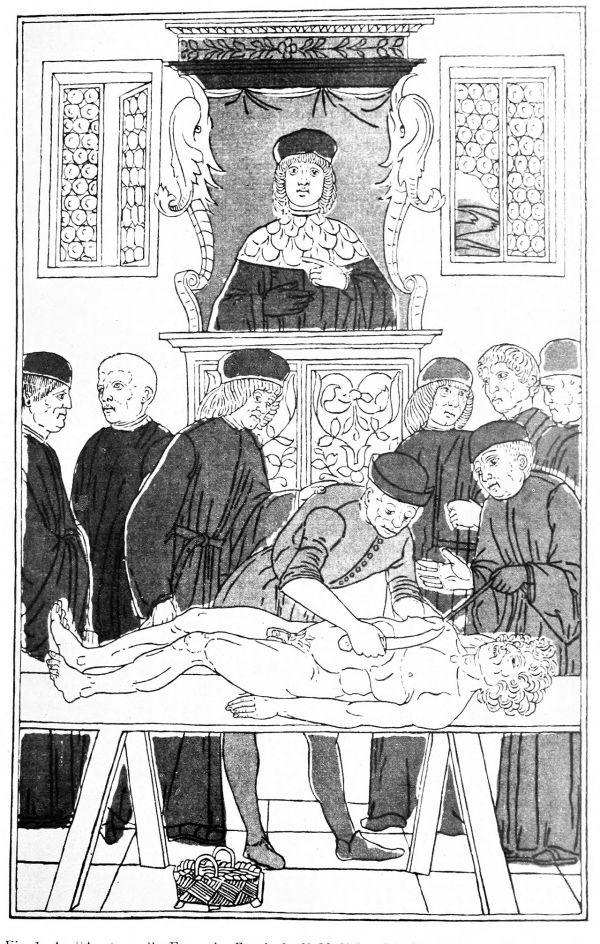

But not only were the Anatomies incomplete, they were rendered ineffectual by the method in which the instruction was imparted. Several illustrations of Anatomies have come dowm from the end of the fifteenth and the first half of the sixteenth century and these show such uniformity in the details of the scene, that they may be taken as representing what had become the customary ritual. In 1491 a German, Johann Ketham, who had lived in Italy, published under the tital Fasciculus Medicinas a collection of medical treatises, among which was the Anathomia of Mondino. This original edition was in Latin, but in 1493 an Italian translation of it was published by Sebastiano Manilio Romano, and in this the treatise of Mondino was supplied with a colored frontispiece showing an Anatomy (fig. 1). Seated in what may be termed a pulpit, whose canopy is supported by two dolphins, is the professor, who is delivering a lecture or more probably reciting passages from Mondino. Before him, stretched out upon a rough wooden table is a male cadaver and near one end of the table stands a demonstrator, holding in his left hand a short wand with which he points to the thorax of the cadaver, indicating the point at which a third person, a surgeon or barber, who holds a curved knife, is to begin his incision. Six other persons represent the spectators, for whose edification the Anatomy is being performed. "What is essentially the same illustration appears in the 1495 edition of Ketham, but it has been reengraved and presents a number of minor changes. Thus the demonstrator no longer holds a wand, but indicates the place for the incision with his finger, and the professor instead of lecturing or reciting is now reading from a book which lies open on the desk before him. So it is also in an illustration of an anatomy contained in Berengario da Carpi’s Commentaries on Mondino published in 1535, and in this case the demonstrator wields a wand. | |||

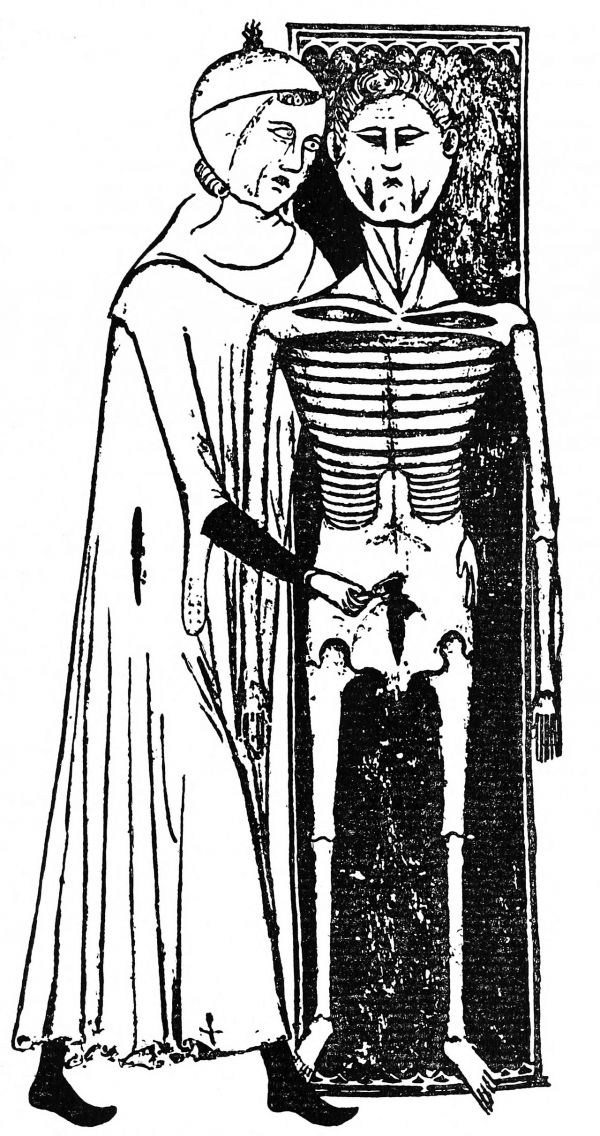

Sometimes the demonstrator is omitted, as in the illustration forming the title-page of the Mellerstatt edition of Mondino (1493), in which the only actors in the scene are the professor seated in an imposing chair with a book in his lap and a youthful assistant who is performing the dissection under direction of the professor. And, indeed, there are illustrations which show the professor condescending to do the actual work of dissection himself as in the Anatomy figured in the French translation by Bartholomseus Anglicus (Lyons, 1482) 18 and in Guido da Yigevano’s anatomical figures (1345) (fig. 2). But it is to be noted that the illustrations which show the professor holding himself aloof from the practical side of the anatomy are associated with various editions of Mondino’s Anatomy, which was for so many years the popular text-book. This fact alone would lead to the belief that these illustrations show the custom generally followed by those who used the book, which is as much as to say that they show the custom generally followed in Anatomies during the latter part of the fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries. But there is further and stronger evidence in confirmation of this belief in the scathing statements of Vesalius in the preface to his De corporis humani fabrica (1543), where he speaks of an Anatomy as — | |||

“A detestable ceremony in which certain persons are accustomed to perform a dissection of the human body, while others narrate the history of the parts; these latter from a lofty pulpit and with egregious arrogance sing like magpies of things whereof they have no experience, but rather commit to memory from the books of others or place what has been described before their eyes; and the former are so unskilled in languages that they are unable to describe to the spectators what they have dissected.” | |||

ie Reproduced by C. Singer in his Studies in the History and Method of Science, Oxford, 1918. | |||

[[File:McMurrich1930 fig01.jpg|600px]] | |||

'''Fig. 1.''' L An “ Anatomy.” From the Fasciculo di Medicina (Venice, 1493). published by C. Singer, Florence, 1925, p. 64. After facsimile | |||

[[File:McMurrich1930 fig02.jpg|600px]] | |||

'''Fig. 2.''' A dissection by Guido da Vigevano (1345). Archiv fur Geschichte der Medizin, vol. 7, pi. 1, 1914. | |||

The recollection of former experiences undoubtedly accounts for the sting of these words, but they tell the same story as the illustrations, the aloofness of the lecturer and his reliance on the written text, and the inefficiency of the dissector. Add to these the haste with which the Anatomy had necessarily to be conducted and it is not difficult to understand why, for so long a period, there should have been no essential progress in anatomy. | |||

{{McMurrich1930 footer}} | |||

Latest revision as of 10:42, 25 March 2020

| Embryology - 20 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

McMurrich JP. Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist. (1930) Carnegie institution of Washington, Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Leonardo da Vinci - The Anatomist

Chapter II Anatomy from Galen to Leonardo

Since, then, a just estimate of Leonardo’s contribution to anatomy can only be arrived at when the state of that science in his day is understood, it will be advisable to consider the opportunities for anatomical studies available during the Middle Ages, the methods employed and the results.

With the death of Galen at the end of the second century of our era, the study of Anatomy entered upon its dark days and for nearly thirteen centuries scarcely a single fact was added to the knowledge of the structure of the human body. Nor does this statement, strong as it is, sufficiently express the condition of anatomical knowledge during this long period; not only was there no progress, there was retrogression. Throughout the Byzantine period synopses of Galen satisfied all demands, the most celebrated being the Collecta medicinalia of Oribasius, compiled at the request of the Emperor Julian and setting forth in concise and orderly succession the statements of the garrulous Galen. Theophilus Protospatharius in the seventh century does seem to have interested himself in dissection and to have added slightly to anatomical knowledge, but such activity was exceptional; and while the period produced some works of importance in the history of medicine and surgery, as far as anatomy was concerned it was almost barren. Later, in Europe the feudalism of the Middle Ages suppressed personal initiative among the mass of the people, each man’s actions and behavior being dictated by the behests of his feudal lord; and among the clerics, from whom light might have been expected, the dogmas of the Church, formluated by the great Councils of the fifth and sixth centuries, defined within narrow limits the mode of thought. Life in all its aspects became highly conventionalized; feudalism produced such conventionalisms as knight-errantry, trial by combat, courts of love and, the climax of them all, the science of Heraldry; philosophy became conventionalized into rhetorical contests between Realists and Nominalists; and art, employed almost exclusively for religious instruction, became stereotyped into the stiff expressionless forms characteristic of early Christian paintings.

Conventionalism is dogmatism crystallized, and dogmatism means finality. What wonder then that the formulation of Christian theology, with its attendant sectarian bitterness, persecutions, riots, and even massacres, resulted in a belief that the last word had been spoken on matters theological. The essence of that theology was absolute faith in the dogmas of the Church ; faith and not reason was the foundation of knowledge of both the supernatural and natural worlds, and of the two worlds it was the supernatural that held the chief place in men’s minds. For their knowledge of natural phenomena they were content to rely upon the statements contained in the writings of the Fathers, these statements in turn being based upon those of earlier writers, provided that these did not conflict with the patristic interpretation of the Scriptures. The character of mediaeval philosophy has been aptly stated in these words:

“A reversed pyramid, whose base was occupied by spiritual matters and of which the imperceptible point of the apex was constituted by man and nature, as things transitory and fleeting — that is the symbol of mediaeval doctrine.” (Solmi, 1910.)

Under such circumstances there was naturally no incitement to personal observation, and experiment and science languished. It became conventionalized largely according to the Galenic tradition, and this tradition came to possess a finality; it was complete and unassailable, there was nothing to be added to it and nothing to be corrected. The word tradition is used advisedly because during the middle ages the original Galen had become practically unknown. Except in Constantinople and probably in such centers as Salerno and Montpellier, Greek had become to all intents a dead language, and Hippocrates, Aristotle and Galen were known only through tradition that had filtered down from the past. Fortunately the works of these authors were not destined for oblivion; they were saved to the World and restored to Europe through the appreciation by the Arabs of what was best in the philosophy and science of the Greeks.

The role of the Arabs in the history of the intellectual development of Europe was an interesting one. Primarily a pastoral and more or or less nomadic people, divided by intertribal feuds, they were welded into a nation by the religious enthusiasm of Mahomet and his small band of early converts, and, after a remarkable career of conquest, they settled down in their capitals to cultivate the arts of peace, just as the Ptolemies had done centuries before in Alexandria. Bagdad and Cordova became centers of learning in which Arabian sages studied and expounded the wisdom of the Greeks. But the Arabs had no knowledge of the Greek tongue and their first care was to secure the services of Syrians, Jews and Nestorian Christians to translate into Arabic the works whose contents they desired to master, and it was not long before all the important scientific and philosophical treatises of classical times appeared in an Arabic guise. From these translations as a source, there flowed a stream of abstracts, commentaries and treatises by Arabian authors, which, however, added little to the volume of human knowledge. For the Arabs showed little originality; what they handed on was Greek science and philosophy with, it is true, some oriental color in its presentation and application, but still essentially Greek. The Arabs contributed little, but they were the keepers of the Light through the Dark Ages and they restored it to the Western world where it had become well-nigh extinct.

The activities of the Arabian commentators could not indefinitely remain unknown to the scholars of western Europe. Already in the latter half of the eleventh century Constantinus Africanus, after spending forty years of his life among the Arabs, was received into the Monastery of Monte Cassino, not far from Salerno, and interested himself in the translation into Latin of Arabic versions of Galen’s Ars parva and Hippocrates’ Aphorisms, as well as of treatises by Ali Abbas and other Arabian commentators of less renown. The capture of Toledo from the Moors by Alfonso VI in 1085 also revealed to the Christian conquerors something of the wealth of the Arabic literature and awakened desire for a better acquaintance with the wisdom of the Arabs. But it was in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries that Arabian influence became most pronounced in Europe. In the twelfth century Toledo became the seat of a bureau of translation organized by the Archbishop Raymond and in the thirteenth century the capture by the Christians of such cities as Cordova and Seville brought further treasures into the hands of the conquerors. Especially under Alfonso X, surnamed The Wise, earnest attempts were made to utilize these treasures to the full; the observations of the Arabian astronomers were collated to form the Alfonsine Tables, while the work of translation went on apace.

But not only were the conditions in Spain favorable for the dissemination of Arabian learning, circumstances made Italy at this same time especially ready for its reception. The Hohenstaufen rulers of Sicily and Naples were strongly biased in favor of the eastern customs and their courts were oriental rather than occidental in their ceremonials. This was especially true in the case of Frederick II, who, notwithstanding that he was under the ban of the Church, led a crusade to the Holy Land and gained important concessions from the Sultan of Jerusalem, with whom he swore a blood-brotherhood. In 1241, Frederick promulgated an edict setting forth the requirements necessary for a license to practice medicine and surgery within his dominions, these requirements demanding that the candidate should have studied the science of logic for at least three years and thereafter should have pursued the study of medicine for five years and have practiced for one year under the guidance of a reputable physician, after which he must satisfy the masters at Salerno of his fitness by satisfactorily undergoing a public examination chiefly on the works of Hippocrates, Galen and Avicenna. It is evident that at this time Arabistic medicine was thoroughly established at Salerno, then at the height of its renown as a center for medical training, but soon to give place to the younger universities of Montpellier and Bologna.

In these, too, Arabian influences became predominant in the thirteenth century. Arnald de Villanova, probably a Spaniard and familiar with both Greek and Arabic, came to Montpellier toward the end of the century, and by his learning, originality and independence contributed greatly to the overthrow of the scholastic methods and to the substitution therefor of the forgotten precepts of the ancient masters, preserved and elaborated by Rhazes and Avicenna. Indeed, he was more than an Arabist; like his contemporary Roger Bacon he advocated and practised observation and experiment as the sources of scientific knowledge, thereby gaining for himself, as did Bacon, reputation as an exponent of the Black Art. His alchemistic predilections did not, however, lead him into mysticism, and his skill as a physician gave an authority to his appreciation of the Arabian contributions to medicine and found a reflection in the compendiums and commentaries of Arabian medical writers that came from representatives of the Montpellier school during the fourteenth century.

The University of Bologna primarily possessed but two faculties, those of Arts and Law, each with its own rector, and although it seems probable that medicine was taught there as early as the eleventh century, it was not until 1260 that the teaching of Thaddeus Alderotti, commonly known as Thaddeus Florentinus, began to attract students in considerable number, and in 1306 the Medical faculty was given an independent rector. Thaddeus was well versed in the medical lore of his day, both Greek and Arabic, and he and his pupils added to the list of commentaries on the works of the ancient and more recent writers. Of these works those chiefly studied by the students were, as at Salerno, the Ars parva of Galen and the Aphorisms of Hippocrates, but acquaintance w r as also required with other works of those authors and with the Colliget of Averrhoes, the Canon of Avicenna and the Almansor of Rhazes. (Rashdall.)

In the thirteenth century, accordingly, the three great medical schools of Europe were deeply under the influence of Arabian authors, and while these restored a better knowledge of the Greeks, they also imposed limitations, since that knowledge came bound by the restrictions imposed by Arab custom. Chief among the results of these restrictions was the divorce of medicine and surgery, which was so pronounced during the Middle Ages. It was due in part to the influence of the oriental tradition against the use of the knife and in part to the general attitude inculcated by Scholasticism. Medicine lent itself more readily to the dialectic dear to the Scholastic, to argumentation as to causes, principles and treatment; whereas surgery required prompt and effective action, and in the foundation of the Universities it was medicine that was taught and practised by the Faculties of Medicine, and surgery was largely left in the hands of barbers, bathkeepers and even public executioners. There were, it is true, some learned surgeons, such as Theodoric and William of Saliceto of Bologna, Lanfranchi and de Monde ville of Paris and Guy de Chauliac of Montpellier, but their number was small and for the most part the physician deemed it beneath his dignity to undertake the treatment of wounds or fractures or operations such as couching and lithotomy, to say nothing of bleeding and tooth extraction. For the physician an intimate knowledge of anatomy was unnecessary; if he knew the position of the various organs of the body and their presumed functions he had all he required, and this he could obtain from a translation of an Arabic summary of Galen’s anatomical treatises, such as is found in Avicenna’s Canon. Ihe original treatises, and especially the de administrationibus anatomicis, remained neglected, even though an Arabic translation of the latter had been made by Honein (Johannitius) or his son-in-law Ilobeisch as early as the ninth century. It was translations of Arabic versions of the Ars medica (commonly known to the Arabists as the Microtechne) and the Methodus medendi {Megalechne) that were especially studied during the Middle Ages: and while the de usu partium awakened some interest for Galen’s anatomical treatises, the summation of the anatomical knowledge of his day, the learned physician felt no need and the barber-surgeon was too ignorant to make use of them.

So the study of anatomy became conventionalized into the reading of a translation into Latin of an imperfect summary by an Arab of Galen’s teaching, and, since its source was Galen, the complete submission to the dictates of antiquity that characterized the Middle Ages gave it an authority and finality that well-nigh suppressed all stimulus to further inquiry. Indeed, ignorance of the original treatises concealed the fact that Galen’s contributions to anatomy were based on the dissection of animals, chiefly monkeys, that his anatomy was not in reality human anatomy, and when this fact was revealed by the investigations of Vesaiius in the sixteenth century their unshaken confidence in the infallibility of Galen led at least one of the Galenists to the conclusion that the structure of the human body mast have altered materially in some respects during the centuries that had elapsed since Galen’s day.

But notwithstanding the profound subservience to dogma, the faint flicker of revolt against it shown by such men as Roger Bacon and Arnald de Yillanova was not entirely extinguished, for the thirteenth century witnessed the encouragement of the study of anatomy by direct observation, such as had not been given since the days of Galen. The Emperor Frederick II, when prescribing the course of study to be pursued by those wishing to practice medicine within his dominions, enacted that no surgeon should be allowed to practise unless “Above all he has learned the anatomy of the human body at the medical school and is fully equipped in this department of medicine, without which neither operations of any kind can be undertaken with success, nor fractures be properly treated.” 1 This does not necessarily mean that the prospective surgeon must have learned his anatomy by the actual dissection of a human body; the School of Salerno was indeed noted for its interest in practical instruction in medicine, but there is no record of a dissection of a human body having been performed under its auspices. Toward the close of the eleventh century, at the period when Arabic influences were beginning to supplant the Greek tradition that had persisted in the School, one Copho, a member of that school, wrote a brief treatise on the anatomy of the pig, Anatomia porci , 2 consisting in its printed form of about two and a half pages and amounting to little more than an enumeration of the various organs to be seen in opening the body of the animal. It describes an autopsy rather than a dissection, but is of interest as evidencing some appreciation of the importance of a knowledge of anatomy based on personal observation. Somewhat more detailed was the Demonstratio anatomica by an anonymous author of the same school, also based on the autopsy of a pig, but these early attempts of the Salernitans to revive the practical study of anatomy were destined to be supplanted by treatises based on the study of the human body, the first attempts in this direction of which there is record, since the days of the Alexandrian anatomists.

It is to Bologna that the credit for the revival of practical human anatomy is due, and it is interesting to note that the long-continued repugnance to the dissection of human cadavers was only gradually overcome by the desire for a more definite knowledge of the pathological changes produced by disease or by the demands of justice for definite evidence in cases of suspected poisoning. The first instance on record of such a revival was a legal autopsy performed by the Bolognese surgeon William of Saliceto on the body of the nephew of the Marchese Uberto Pallavicino, who was suspected of having died from the administration of poison. William of Saliceto was the author of a Cyrurgia, written in 1275, the fourth book of which is devoted to a compendium of Anatomy in five chapters. It is Galenic anatomy, similar to that found in mediaeval manuscripts, and, to judge from the use of Arabic terms for certain parts, was based upon an Arabic source, probably Avicenna. That William, “qui Gulielmina dicitur,”

1 J. J. Walsh, Mediaeval Medicine, London, 1920. The translation is made from a copy of the edict published in Huillard-Brehollis’ Diplomatic History of Frederick II, with Documents, Paris, 1851-1861.

2 A translation of this and also of the Demonstratio mentioned below will be found in G. W. Corner, Anatomical Texts of the Earlier Middle Ages. Carnegie Inst. Wash., 1927.

had practical experience in dissection is indicated by the directions he gives as to how the incisions should be made for the exposure of various parts and by his statement that a certain duct, wrongly described by his source as existing, was unknown to him.

A few years later (12S6) a Parmesan or Lombard physician is reported to have made autopsies of the bodies of persons who had died of an aposthematous pestilence (Solmi, 190G) and in 1302 a postmortem examination was ordered of the body of one Azzolino, who was suspected of having been poisoned. The examination was made by Bartholomeo da Varignana, a famous teacher and practitioner in Bologna, with four associates, and these reported —

“quod dictum Azzolinum ex veneno aliquo mortuum non fnisse, sed potius et certius ex multitudine sanguinis aggregati circa venam magnam qua? dicitur vena chilis, et venas epatis propinquas eidem, unde prohibita fuit spiritus per ipsam in totum corporis effluxio, et facta caloris innati in toto mortificatio, seu extinctio, ex quo post mortem celeriter circa totum corpus denigratio facta est, quam paxionem adesse prrcdicto Azzolino praedicti Medici sensibiliter cognoverunt visceribus ejus anathomice circumspectis.” 3

The recognition of autopsies given by the authorities in this case was no doubt an important factor in bringing about a greater freedom in the investigation of human cadavers, and it seems probable that early in the fourteenth century advantage was taken of this freedom for the performance of autopsies at Bologna as a means of anatomical instruction. In 1316 there appeared a text-book of anatomy from the pen of Mondino di Luzzi which was destined to supplant that portion of the first book of Avicenna’s Canon which treated of anatomy. 4 It remained the favorite anatomical text-book for over two centuries, partly because of its directness and simplicity of statement, partly because of its recognition of the practical application of anatomy and partly, and largely, because in the treatment of the subject it followed the order in which the various organs would be exposed in an autopsy. In other words it was a Manual of Practical Anatomy rather than a systematic treatise of the subject. It bears evidence in its arrangement that its author is treating his subject on the basis of personal practical experience and, indeed, in the text there is a statement that in 1315 he performed autopsies on two female subjects; but nevertheless the work makes no contribution to the more accurate knowledge of anatomy; it gives nothing beyond what was contained in the Arabian treatises; it repeats their errors and shows their influence in the use of Arabic terms for many of the organs. The contents of Mondino’s work will later be considered more in detail, since it was one of the sources of Leonardo’s knowledge of anatomy; its present significance is that it indicates an increasing interest in the practical study of the human body and it probably had influence in further promoting that interest.

3 M. Medici, Compendia Slorico della Scuola Anatomica di Bologna, Bologna, 1857.

4 See G. Martinotti, L'insegnamcnto dell’ Anatomia in Bologna prima del secolo XIX, Bologna, 1911, page 61, where is quoted a portion of a statute of the University of 1405 in which, in the prescription of texts to be studied in the successive years of the medical course, the first book of Avicenna is mentioned always with the addition of the words “excepta anathomica.”

After Mondino’s time the dissection of human cadavers for the purpose of instruction became of frequent occurrence. Guido de Vigevano, who was physician to the French King Philippe de Valois, in the concluding chapter of his Liber notabilium, which consists mainly of excerpts from translations of Galen and was written in 1345, endeavors to demonstrate the structure of the human body by a series of eighteen figures, which he believes himself capable of doing “cum pluribus et pluribus vicibus ipsam (anathomiam) feci in corpore humano.” 6 Similarly Guy de Chauliac, the greatest of the surgeons of Montpellier, states in his Grande Chirurgie that his Bolognese teacher, Bertucci, who died of the Black Plague in 1347, performed many Anatomies, each consisting of four lessons, as follows:

“In the first he considered the nutritive organs because they perished soonest, in the second the spiritual organs, in the third the animal organs, and in the fourth the extremities .” 6

Nor was the performance of Anatomies or autopsies limited to Bologna. Gentilis da Foligno, who for a time taught at Bologna and at Perugia and who like Bertucci, fell a victim to the Black Plague, is recorded as having performed an autopsy at Padua in 1341, in which he discovered in the gall bladder of the subject “a green stone,” 7 and further it is also on record that the anatomists of Perugia, when making an anatomy in 1348, found in the neighborhood of the heart a small sac full of poison, the subject having died of an epidemic (Solmi, 1906).

The performance of Anatomies was not, however, allowed to proceed without let or hindrance. Even in Mondino’s time there is record (1319) of a trial in Bologna of four Masters who were accused of having disinterred the body of an executed criminal and of having transported it to the house in which a certain Master Albertus of Bologna was accustomed to lecture, a witness testifying that there he had seen Master Alberto with four other Masters and others persons —

“existentes super dictum corpus cum rasuris et cultellis et aliis artificiis et sparantes dictum hominem mortuum et alia facientes qute spectat ad artem medicorum .” 8

8 E. Wickersheimer, L“Anatomie” de Guido de Vigevano, medecin de la reine Jeanne de Bourgogne (1345), Arch. f. Gesch. derMedizin, vol. 7, 1913.

6 Guy de Chauliac, La Grande Chirurgie, restituee 'par M. Laurens Joubert, Rouen, 1632. This is one of the many printed editions of this famous work, which was originally written in 1363.

7 M. Roth, Andreas Vesalius, Bruxellensis, Berlin, 1892.

8 See M. Medici, loc. cit. p. 12.

In France, or at least in Paris, it would seem that in the fourteenth century the dissection of the human body was prohibited by the clerical authorities except under a special privilege, concurrent evidence to that effect being furnished by Henri de Mondeville and Guido de Vigevano. De Mondeville was by birth a Frenchman, but he was probably educated in Italy, although there is no direct evidence in support of this idea. At all events he was at Montpellier in 1304 and demonstrated anatomy there, or rather, as Guy de Chauliac informs us, he “pretended to demonstrate anatomy” by the use of thirteen figures. Thence he passed to Paris where he became surgeon to Philippe le Bel, to whom he dedicated his Chirurgie, begun in 1306 but never completed. In the first part of this he treats Anatomy, essentially on the basis of Avicenna’s teaching, but with indications of the methods to be pursued in demonstrating it and in this connection he states —

“Si debeant (corpora) servari ultra 4 noctes aut circa et exinde a Romana Ecclesia speciale privilegium habeatur, findatur paries ventris anterior a medio pectoris usque ad pectinem. . . ” 3

Guido de Vigevano, whose early training was presumably obtained in Italy, also based his teaching on figures, making these, indeed, the essential part of his chapter on anatomy, giving as his reason for so doing “Quia prohibitum est ab Ecclesia facere anothomiam in corpore humano.” 10 It is noteworthy that both these works were written in Paris at a time when autopsies were being freely performed in Italy, a fact which suggests that the prohibition may have been a local one. No general enactment of the Church on the question of Anatomies is known, but it has been held that the Bull of Boniface VIII De Sepulturis, issued in 1300, had a prohibitory effect on the practical study of anatomy. The Bull had, however, quite another purpose as is shown by its title which may be translated thus:

“Those eviscerating the bodies of the dead and barbarously boiling them in order that the bones, separated from the flesh, may be carried for sepulture into their own country are by the act excommunicated.” 11

It was called forth by a practice that had arisen during the Crusades, and while it is possible that it was interpreted by the Parisian clergy as setting a ban on Anatomies, no such interpretation, apparently, was placed upon it in Italy, or if it was, it was short lived. Indeed Alessandro Benedetti, a contemporary of Leonardo, states in his Historia corporis humani (1497) that anatomists were even in the habit of preparing skeletons by boiling without fear of excommunication.

9 J. L. Pagel, Die Chirurgie des Henri de Mondeville , Berlin, 1892.

10 E. Wickersheimcr, loc. cit., p. 13.

11 The Bull is quoted in its entirety in a paper by J. J. Walsh, The Popes and the Ilistonj of Anatomt/, Medical Library and Historical Journal, vol. 1, 1904. See also Mediaeval Medicine, London, 1920, by the same author.

The Humanistic movement, born in Italy in the fourteenth century, manifested itself primarily in literary studies, but soon expanded to include other fields of intellectual activity. Underneath the literary movement and bearing it along was the awakening spirit of the Renaissance, the yearning for emancipation from the domination of dogma, the dissatisfaction with knowledge acquired at second hand, the desire to learn and know from personal observation. This manifested itself in an increasing demand for opportunities for Anatomies, sufficiently insistent to compel from the authorities enactments providing a definite supply of cadavers to be used for such purposes. The first of these enactments of which there is record was passed by the Great Council of Venice in 1368, decreeing that an Anatomy should be made once in each year before the physicians and surgeons, the dissections, according to Nardo, 12 being performed in the Hospital of Ss. Peter and Paul. Shortly after, probably in 1376, a similar privilege was granted to the Medical faculty of the University of Montpellier, this privilege being confirmed several times in later years up to the close of the fifteenth century.

It was in that century, however, that the granting of such a privilege became generally established in Italy, indicating a widespread interest in the study of Anatomy. It has been shown that early in the fourteenth century autopsies and Anatomies had been conducted with some frequency at Bologna, but no records have yet been found of decrees legalizing the practise in that municipality. In the early days of the Universities, the relations between the students and teachers were more intimate than in later days. The Italian Universities w T ere primarily guilds of students as contrasted with the guilds of Masters of which the University of Paris was the prototype:’ 3 the students selected their own Masters, the instruction they received was according to personal arrangements into which they entered with their Masters and much of the teaching was done in the houses of the Masters. Martinotti 14 has shown that even anatomy was taught in this extra-mural fashion and continued to be taught privately long after the institution of Public Anatomies, even, indeed, until Galvani’s time, at the close of the eighteenth century, and later. The responsibility for the supply of subjects for these private Anatomies appears in the early days to have rested with the students, an arrangement that naturally led to disturbances and conflicts, to obviate which the Statutes of the University of 1405 prescribed that no one, doctor or student, should be allowed to have possession of a body, unless he should previously have obtained a license for that purpose from the Rector. But this plan, apparently, was not quite satisfactory, and in 1442 it was modified by requiring the Podesta of Bologna to furnish each year at the request of the Rector, two cadavers upon which Anatomies might be made, a condition being made, however, that the cadavers must be obtained from places not less than thirty miles distant from the city of Bologna. This limitation was removed in 1561, after which date the bodies of persons who had been resident even in the suburbs of Bologna might be taken, “modo cives honesti non sint et superioribus ea dare placeat.”

12 Quoted by Bottazzi (1907).

13 H. Rashdall, The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages, Oxford, 1895.

14 G. Martinotti, loc. cit., p. 12.

Nor was Bologna the only Italian city in which the practical study of anatomy was zealously conducted during the fifteenth century, indeed, the renown of Padua as a center for medical instruction was almost, if not quite, as great as that of the sister university. The charter of the University of Padua was granted by the Emperor Frederick II in 1222, and it is probable that it undertook instruction in medicine from its foundation. It is also probable that Anatomies were conducted there even in the fourteenth century, for it was a professor from Padua who performed the first Anatomy in Vienna in 1404. At the beginning of the fifteenth century Padua fell under the domination of Venice (1405) and after that date it quickly rose to great prominence as an anatomical center. Autopsies are on record as having been performed in 1420 and again in 1430, and Montagnana in his Consilia, written in 1444 while he held a professorship of medicine at. Padua, states that he had witnessed fourteen Anatomies. There is record of a public Anatomy held in 1465 at which the doctors discussed all the doubtful points concerning the structure of the body, “atque tandem corpus cum maxima festivitate humatum.” It was not until 1495, however, that a statute was passed requiring the annual delivery to the University for anatomical purposes of two bodies, one male and one female.’ 5 A similar regulation was in force in the fifteenth century at Siena, Perugia, Genoa and Ferrara, and in 1501 at Pisa, while it is known that early in the sixteenth century dissections were made at Pavia by Marc Antonio della Torre.

It is evident from these data that in the time of Leonardo, the latter half of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century, the dissection of the human body was a well-recognized feature of medical instruction; the long-standing prohibition of it, imposed partly by general sentiment and partly by religious opinion, had given way to the spirit of the Renaissance. It will be of interest later to consider the conditions obtaining at Florence, where Leonardo entered upon his anatomical studies, but here a brief account of the methods adopted in the performance of an anatomy will not be amiss, since it will explain the failure of the early anatomists of the Renaissance to advance in their knowledge of anatomy and the greater success of Leonardo.

16 M. Roth, Andreas Vesalius, Bruxcllcnsis, Berlin, 1892.

Why was it that with all their opportunities for direct observation, the anatomists of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries added little or nothing to the scanty and superficial description of the human body contained in the Canon of Avicenna? Why did they fail even to reach the standard of exposition set up by Avicenna? Because, in the first place, Avicenna was epitomizing the anatomy of Galen while the more modern writers were either epitomizing Avicenna’s epitome, not yet having access to the original Galenic treatises, or else, as in the case of Mondino, were describing on the basis of Avicenna’s epitome what could be seen in an Anatomy, and their Anatomies were limited in their duration, since they possessed no means of preserving the bodies from putrefaction, and in the warm climate of Italy the work could not be prolonged over more than three or four days. Nor was it carried on without intermission during the available time, but apparently was divided into usually four demonstrations in the manner described by Bertucci (see p. 13) ; and furthermore the time available for observation was frequently greatly curtailed by prolonged discussion by the Masters present, of moot points suggested by the demonstration. With these limitations of time it is evident that in the Anatomies of the fifteenth century only a superficial examination of the more conspicuous organs of the body could be made; of detailed dissection there was none. Mondino excuses himself for omitting a discussion of the “simple parts” because these were not perfectly apparent in dissected bodies, but could only be demonstrated in those that had been macerated in running water. He was also accustomed to omit consideration of the bones at the base of the skull, because these were not evident unless they had been boiled, and to do this was to sin, and, similarly, he omitted the nerves which issue from the spinal column, because they could be demonstrated only on boiled or thoroughly dried bodies and for such preparations he had no liking. So too Guy de Chauliac and Berengarius da Carpi maintained that the muscles, nerves, blood-vessels, ligaments and joints could only be studied in bodies that had been macerated in flowing or boiling water or else thoroughly dried in the sun, and there is no evidence that such preparations were demonstrated at the Anatomies. These were little more than demonstrations of the organs contained in the three ventres of the body, the abdomen with the membra naturalia ; the thorax with the membra spiritualia and the head with the membra animalia.

But not only were the Anatomies incomplete, they were rendered ineffectual by the method in which the instruction was imparted. Several illustrations of Anatomies have come dowm from the end of the fifteenth and the first half of the sixteenth century and these show such uniformity in the details of the scene, that they may be taken as representing what had become the customary ritual. In 1491 a German, Johann Ketham, who had lived in Italy, published under the tital Fasciculus Medicinas a collection of medical treatises, among which was the Anathomia of Mondino. This original edition was in Latin, but in 1493 an Italian translation of it was published by Sebastiano Manilio Romano, and in this the treatise of Mondino was supplied with a colored frontispiece showing an Anatomy (fig. 1). Seated in what may be termed a pulpit, whose canopy is supported by two dolphins, is the professor, who is delivering a lecture or more probably reciting passages from Mondino. Before him, stretched out upon a rough wooden table is a male cadaver and near one end of the table stands a demonstrator, holding in his left hand a short wand with which he points to the thorax of the cadaver, indicating the point at which a third person, a surgeon or barber, who holds a curved knife, is to begin his incision. Six other persons represent the spectators, for whose edification the Anatomy is being performed. "What is essentially the same illustration appears in the 1495 edition of Ketham, but it has been reengraved and presents a number of minor changes. Thus the demonstrator no longer holds a wand, but indicates the place for the incision with his finger, and the professor instead of lecturing or reciting is now reading from a book which lies open on the desk before him. So it is also in an illustration of an anatomy contained in Berengario da Carpi’s Commentaries on Mondino published in 1535, and in this case the demonstrator wields a wand.