Book - Manual of Human Embryology 11E

| Embryology - 19 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Bardeen CR. XI. Development of the Skeleton and of the Connective Tissues in Keibel F. and Mall FP. Manual of Human Embryology I. (1910) J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

XI. Development of the Skeleton and of the Connective Tissues

By Charles R. Bardeen, Madison, Wis.

- Skeleton and Connective Tissues: Connective Tissue Histogenesis | Skeletal Morphogenesis | Chorda Dorsalis | Vertebral Column and Thorax | Limb Skeleton | Skull Hyoid Bone Larynx

E. The Skull, Hyoid Bone, and Larynx

General Features

We may distinguish in the skull, considered purely topographically, a neural and a visceral region. The neural region serves to protect and support the brain and sense organs; the visceral, for the alimentary and respiratory tracts. A sharp demarcation between the two regions is not possible. Thus the base of the skull, especially its axial portion, has relations to both regions, and through change of function changes in the two regions may be brought about (ear ossicles). We shall begin with a description of the axial part of the skull, which generally is counted a part of the neural region.

The axial region is that portion which is continued forward from the vertebral axis. It includes the basal portion of the occipital bone and the body of the sphenoid. In the embryo the chorda dorsalis extends anteriorly to the hypophysis. The axial region of the skull is thus divisible into chordal and prechordal portions, the former lying posterior, the latter anterior to the hypophysis. The chordal portion, is further divisible into an otic part, which corresponds roughly with that portion of the base of the skull which articulates with the temporal bone, and a postotic part, which extends to the otic part from the spinal column. The prechordal region supports the orbitotemporal and ethmoidal portions of the skull.

The neural region lies dorsal, lateral, and apical from the axial region with which it is intimately associated. It serves to encapsulate the brain (cranial cavity) and the organs for hearing, smell, and vision (petrous portion of the temporal bone, orbital and nasal cavities).

The visceral region lies chiefly ventral and ventrolateral to the axial region. In part it is closely associated with the neural region. It includes the pterygoid processes of the sphenoid, the hard palate, the bones of the upper and lower jaws, and the hyoid bone. From the primitive visceral skeleton of the head are also derived the bones of the middle ear and the cartilages of the larynx.

In the development of the complex skeletal apparatus of the head, overlapping blastemal or membranous, chondrogenous, and osseogenous stages may be distinguished. The origin of the mesenchyme of the head has already been described (p. 297). It is at first rather loose in structure, but soon becomes condensed in various regions. This condensation usually marks the beginning of the differentiation of the mesenchyme into muscles and into various connective-tissue structures of more or less definite form, tendons, fascias, dermis, submucous coats, membranes of the brain, and portions of the organs of special sense and the anlages of the skull and the larynx. The membranous anlage of the skeleton of the head is gradually developed from several centres of condensation. In part it is transformed into cartilage, forming the chondrocranium.

The chondrocranium arises through the fusion of a considerable number of cartilages which originate from independent centres of chondrification. Some of these centres of chondrification arise in mesenchymatous tissue which shows no well-marked condensation preceding the formation of cartilage. The transformation of membranous tissue into cartilage in some instances takes place very rapidly, in other instances slowly.

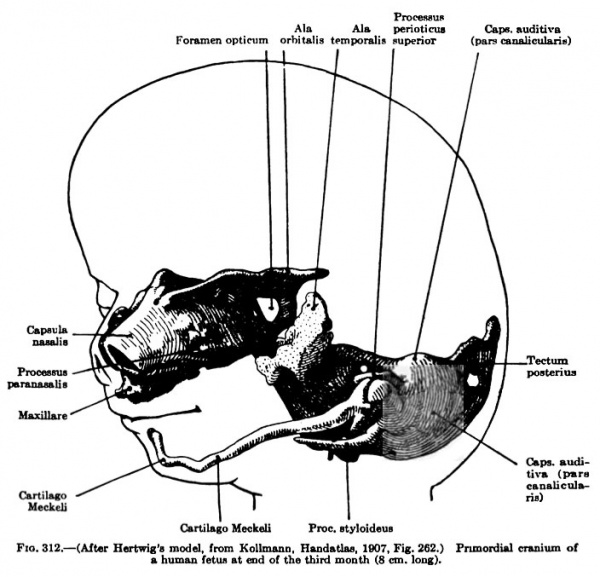

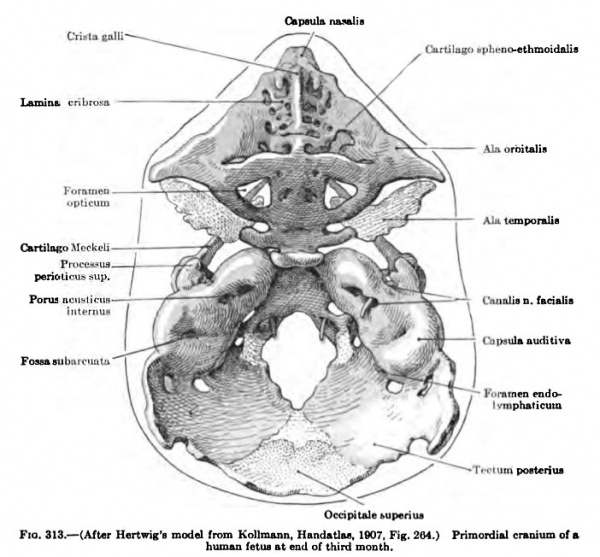

The chondrocranium reaches its highest relative development in the third month of intra-uterine life. At this period it comprises the axial region of the skull, the auditory and olfactory capsules, the orbital wings and the bases of the temporal wings of the sphenoid, the occipital condyles, and the tectum posterius which lies dorsolateral to the occipital and temporal regions (Figs. 312 and 313). In the first and second branchial arches well-marked cartilaginous skeletal structures are formed ; in the first the malleus and incus; in the second, the stapes and the styloid process of the temporal bone. Ventrally the second, third, fourth, and fifth branchial arches give origin to a cartilaginous hyoid bone and to some of the cartilages of the larynx.

Ossification begins during the second month in man. The skeleton of the head at this period, with the exception of the chondrocranium described above, is composed of membranous tissue. Ossification takes place in part directly in the membranous tissue of the skull, in part in the chondrocranium.

Most of the individual bones of the human skull arise from two or more centres of ossification, and many of them are partly membranous, partly cartilaginous in origin. Neither the centres of ossification nor the bones developed from them correspond very perfectly with the centres of chondrification from which the chondrocranium arises.

The chondrocranium is mainly, but not completely, replaced by bone. The cartilages of the septum and alse of the nose, and the fibrocartilago basalis, for instance, represent remnants of the chondrocranium. Parts of the primitive cartilaginous skeleton are converted into fibrous tissue instead of into bone. The stylohyoid ligament is an example of this.

Gaupp has shown that the cavum cranii of mammals is not quite homologous with that of reptiles. On each side there lies a space, the cavum epitericum, above the ala temporalis, which in reptiles is outside of and in mammals forms a part of the cranial cavity (Mead, 1909, Voit, 1909).

We may now consider the more important stages in the development of the skull in somewhat greater detail.

Blastemal Period

At the end of the second week of intra-uterine development the chorda dorsalis extends to the dorsal margin of the buCoopharyngeal membrane (Fig. 229). On each side of it mesenchyme fills in the space between the brain, pharynx, and ectoderm. As the head develops the mesenchyme increases in amount. It extends dorsally and apicalward so as to surround completely the brain and its appendages. When the flexures of the brain appear, mesenchyme extends into the fissures between the various segments of the neural tube. An especially large fold of mesenchyme Mittelhirnpolster) is formed beneath the midbrain flexure (Fig. 266). The chorda dorsalis for a time remains attached to the ectoderm of the caudal wall of the hypophyseal pocket, then loses this connection and terminates free in the tissue immediately behind the hypophysis beneath the midbrain flexure.

Toward the end of the fourth week the post-otic portion of the axial region of the skull becomes marked by a condensation of mesenchyme. This condensed tissue or "occipital plate" is not sharply outlined. It consists of a blastemal central portion with two lateral processes on each side, a caudal rod-like "neural" process and a flat apical process (see Fig. 231). Between these two processes run the roots of the hypoglossal nerve. The chorda dorsalis, surrounded by a perichordal sheath, lies in the sagittal axis of the plate. At this period it may still be united to the epithelium of the pharyngeal vault.

It has been previously pointed out that the post-otic axial region of the manamalian head may be considered to be composed of at least three segments comparable to the spinal segments. This segmentation is best marked by the myotomes which develop in the lateral portions of these segments. That part of the occipital plate which lies in the most distal of the segments resembles in some respects a spinal sclerotome tsee p. 334).

The apical end of the occipital plate extends into a thin layer of dense tissue which surrounds the dorsal portion of the pharynx. The chorda dorsalis extends forward in this tissue nearly to the hypophysis. The tissue in which the chorda runs becomes much thicker near the hypophysis than where it lies opposite the otic labyrinth. The latter is surrounded by a layer of condensed tissue connected for a short distance with the retropharyngeal tissue.

The mesenchyme in the visceral region of the head is much condensed, but as yet no skeletal structures are definitely outlined.

The chorda dorealis is composed of densely packed cells surrounded by a very faint sheath. Outside of the chordal sheath there is a weU-marked layer of mesenchyme cells or perichordal membrane. In the region of the spine and of the occipital plate a space is seen between the chordal sheath and the perichordal membrane. This space is not seen apical to the occipital plate.

During the early part of the second month the membranous anlage of the skull becomes extensively developed.

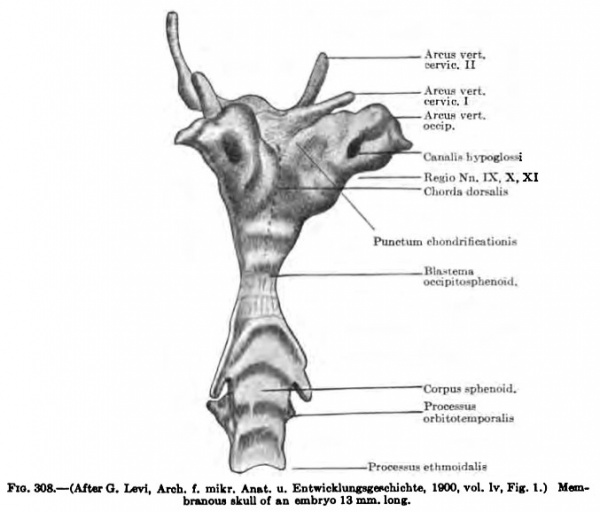

Fig. 308. — (After Q. Levi, Arch. f. mikr. Anst. u. EDdrickliuwefchinble, 1900, vol. Iv, Fir. t.) Membranous skull of an embryo 13 mm long.

The anterior and posterior lateral processes of the occipital plate become united lateral to the hypoglossal nerve, so that the hypoglossal foramen is completed and the membranous pars lateralis of the occipital is formed. This pars lateralis is continued into the membranous vault of the skull, the origin of which is described below.

The condensed tissue of the post-hypophyseal region increases in amount and extends about the hypophyseal pocket into the region apical from this, thus completing the anlage of the body of the sphenoid {Fig. 308). This gives rise to orbitotemporal and ethmoidal processes.

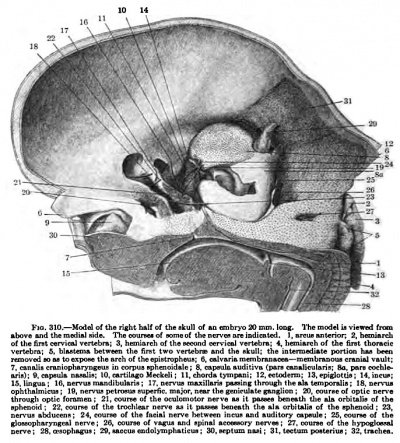

The orbitotemporal process is first marked by a mass of dense mesenchyme which extends ventrolaterally toward the ectoderm caudal to the optic cup. It is connected with dense tissue which surrounds the anlage of the orbit and with the anlages of the membranous fioor and vault of the skull. In it are developed the orbital and temporal wings of the sphenoid, the origin of which will be described in connection with the chondroeranium. The ethmoidal process extends anteriorly in the median line from the anlage of the body of the sphenoid into the region between the nasal fosste. It forms the anlage of the nasal septum and gives rise to parts of the membranous floor of the cranial cavity and the roof of the mouth (Fig. 310).

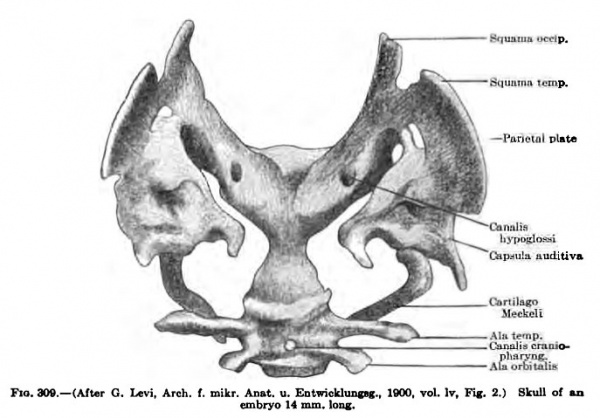

Fig. 309. — (After C. Levi, Arch. t. mikr. Anat.) Skull of a embryo 14 mm, long.

The tissue of the capsules of the labyrinth increases in amount as the labyrinth becomes differentiated. The tissue which encloses the region of the semicircular canals and the vestibule forms an oval mass the outlines of which do not conform to that of the enclosed canals (Fig. 309). This tissue is less dense than most parts of the membranous skeleton of the head and at an early period becomes transformed into embryonic cartilage (see p. 407). The cochlear portion of the labyrinth (Fig. 310) is enclosed by a dense mesenchyme which becomes converted into cartilage at a later period. lateral from the nasal fossa the tissue becomes generally somewhat condensed, though less so than the tissue in the septum. In the perinasal tissue condensation gradually marks out the lateral and ventral portions of the nasal capsule and the membranous floor of the ethmoidal and orbital portions of the cranial cavity (Fig. 310). From the lateral wall membranous processes project into the nasal fossa. These are the anlages of the conchae.

The floor of the cranial cavity at this period is formed posteriorly by the occipital plate with its lateral processes and by the capsule of the labyrinth. Between the two is a fissure for the passage of the glossopharjTigeus, vagus, and spinal accessory nerves and the jugular vein (Fig. 309). Apically the floor is formed by a thin sheet of condensed tissue, which is slightly marked over the ethmoidal region where the olfactory nerve passes through it and is better marked on the anterior medial portion of the roof of the orbit. This portion is connected caudally with the orbital wing of the sphenoid (Fig. 310).

Between the orbital region and the capsule of the labyrinth, in the vicinity of the Gasserian ganglion, the floor of the cranial cavity is incomplete. More medially the floor of the cranial cavity is formed by two membranes, one of which arises from the anterior margin of the auditory capsule and the neighboring part of the body of the sphenoid, and the other from the posterior margin of the orbital wing of the sphenoid. These two membranes extend upwards into the midbrain fold, fuse, and furnish a short central skeletal support for the mesenchyme in this fold (Fig. 266). They enclose the lateral process of Rathke's pocket. They form no part of the definitive skeleton.

The roof of the cranial cavity is formed by a dense membranous layer which first becomes marked at the side of the head in embryos 9-11 mm. in length. At this stage there is a plate of dense tissue formed between the caudolateral margin of the orbit and the caudal lateral process of the occipital plate. It lies lateral to the Gasserian ganglion and the capsule of the labyrinth, with the latter of which it comes in contact. Below it is connected with the orbitotemporal process and the dense tissue of the region of the branchial clefts.

This membrane gradually extends so that it forms a complete membranous vault. Ventrally it is continuous with the ventrolateral margin of the membranous covering of the ethmoidal and orbital portions of the floor of the cranial cavity. Laterally it becomes connected with the temporal wing of the sphenoid, the auditory capsule, and the lateral part of the occipital. Caudally it is continued into the much thinner membrana reuniens dorsalis of the spinal canal.

During the period under consideration the brain only partially fills the cranial cavity. A large amount of loose mesenchyme intervenes between the brain and the floor and vault of the cranial cavity. This tissue is especially abundant in the region of the flexures of the brain and about the hemispheres (Fig. 266). In it the falx cerebri and other membranous supports of the brain are developed. During the latter part of the second month an extensive plexus of vessels develops on the cerebral side of the membranous vault.

The anlages of the alveolar borders of the upper and lower jaws become marked by condensation of tissue along the upper and lower margins of the entrance into the oral cavity. This condensed tissue at first forms a flat plate, but later sends processes in an aboral direction.

Chondrogenous Period

A large amount of study has been devoted to the development of the chondrocranium or primordial cranium in the different vertebrates. An excellent summary of the chief literature on the subject is given by Gaupp (1906). The chief work on the development of the human chondrocranium has been done by Dursy, Spoendli, Hannover, Froriep, v. Noorden, Jaccby, O. Hertwig, and Levi. The development of the chondrocranium in man begins early in the second month. Its relatively most complete differentiation is reached toward the end of the third month, although some parts of it undergo a still greater elaboration before conversion into bone.

At the end of the third month (see Figs. 312 and 313) the caudal half of the chondrocranium forms a ring of cartilage about the posterior portion of the brain. The thick ventral portion of this ring comprises medially the basilar portion of the occipital and laterally the capsule of the labyrinth and the partes laterales of the occipital. The dorsal portion of the ring is composed of a thin plate of cartilage, the tectum posterius, the only part of the cranial vault which becomes cartilaginous in man. In the partes laterales of the occipital the hypoglossal foramina may be seen. The processes which bound them anteriorly serve as the posterior boundaries of the jugular foramina.

The caudal portion of the chondrocranium is united to the apical portion by the relatively slender body of the sphenoid. At the junction between the two is a large dorsum sellsB.

The apical portion from above appears somewhat quadrangular. The caudal angle of the quadrangle forms the body of the sphenoid ; the apical angle, the ventral end of the nasal capsule ; and the lateral angles, the tips of the alae orbitales of the sphenoid. In the mid-line a well-developed nasal septum extends forward from the body of the sphenoid. Seen from the side (Fig. 312) the dorsal surface of the body of the sphenoid and the dorsal and anterior margins of the nasal septum form three sides of a hemihexagon. At the junction of the dorsal and anterior margins of the nasal septum there is a prominent crista galli.

From the body of the sphenoid the temporal and orbital wings project laterally. On each side of the dorsal margin of the nasal septum there may be seen a quadrangular cribriform plate, the lateral margins of which are united to the ala orbitalis by plates of cartilage (cartilagines spheno-ethmoidales) which extend over the orbit. There is also a plate of cartilage which extends to the ala orbitalis from the dorsal surface of the axial region of the chondrocranium near the junction of the sphenoidal and ethmoidal regions.

The nasal fossae are bounded laterally by a plate of cartilage which is united posteriorly to the anterior extremity of the body of the sphenoid, dorsally to the lateral edge of the cribriform plate, and anteriorly to the nasal septum. The inferior margin of this lateral plate curves inwards, but does not extend to the nasal septum. The inferior surface of the nasal fossa thus is not closed off by cartilage. Anteriorly, however, the inferior aperture is rendered very narrow by a paraseptal cartilage (see p. 413). From the lateral nasal cartilage there arises a short process which encircles a part of the nasolachrymal duct (processus paranasalis).

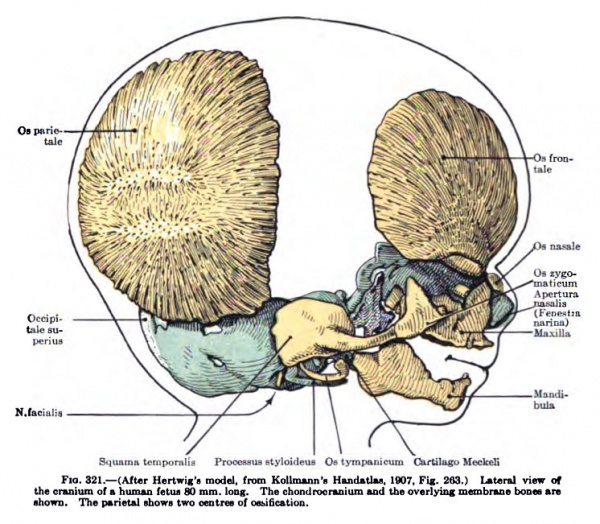

The orbit is bounded above by the orbital wing of the sphenoid and the processes attached to this; posteriorly by the lateral extremity of the ala temporalis, much of which has already become ossified; and medially by the lateral nasal cartilage. The floor and the lateral part of the roof of the orbit are formed of membrane bone. At this period the parietal, frontal, nasal, and lachrymal bones, the maxilla, the ej^gomaticum and the squama temporalis, the tympanicum, the laminae mediales of the pterygoid process of the sphenoid, the vomer, and the palatine bones are beginning to become ossified as membrane bones (see Fig. 321).

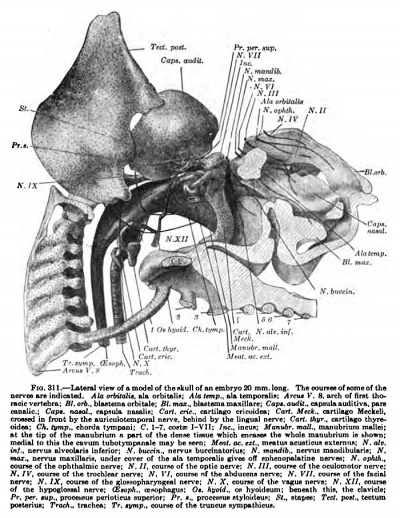

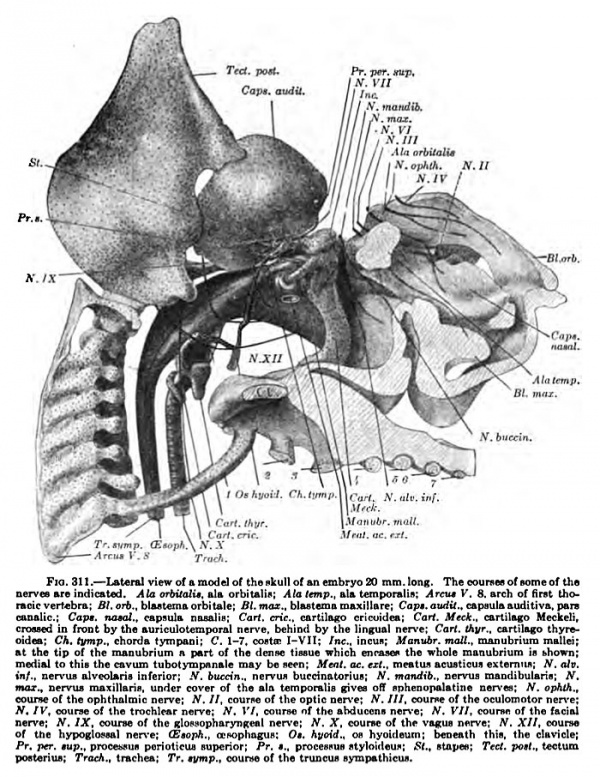

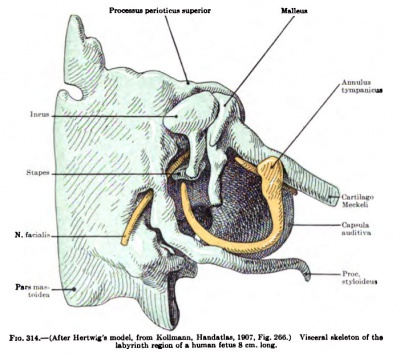

Those portions of the skeleton of the head derived from the visceral arches are shown in Figs. 311, 312, and 314. From the mandibular arch are derived Meckel's cartilage, the malleus, and the incus. The malleus and incus have nearly their definitive form, although relatively far greater in size than in the adult skull. Meckel's cartilage, which is continued from the capitulum of the malleus into the mandible, is a temporary structure which disappears at a later period. It is at this time flanked by a mandible formed of membrane bone.

The stapes, which at this period has its characteristic form, and the styloid process of the temporal bone are derived from the second branchial arch. The cartilaginous hyoid bone and the chief laryngeal cartilages are clearly outlined, although the hyoid bone is not thus represented in the model. These cartilages are derived from the second, third, fourth, and fifth branchial arches.

The skeleton of the rudimentary head of amphioxus is composed of the chorda dorsalis, membranous tissue, and a few scattered structures, cartilaginous in character. The cyclostomes have a rather complicated chondrocranium, the roof of which is formed of membrane except for a slender tectum synoticum. The occipital region is missing" and the cranium terminates caudally in the labyrinth region. Li selachians the cranial cavity of the cartilaginous skull has a complete roof, side walls, and floor, but is open in front and behind (f. magnum). In the vertebrates above the selachians a chondrocranium is formed during embryonic development, but the degree of its elaboration and the extent to which it is retained in the adult skull vary greatly in the different classes of vertebrates. In the higher vertebrates the chondrocranium is largely replaced by bone, partly of the investment (membranous), partly of the substitution (cartilaginous) type. In man the chondrocranium is relatively slightly developed and the investment bones are relatively extensive.

Having considered briefly the cartilaginous skeleton of the head at the height of its development, we may now take up in more detail the development of its component parts.

Occipital Region, the Capsule of the Labyrinth, and the Tectum Posterius

Base and Partes Laterales of the occipital. — ^A brief description of the development of the posterior part of the occipital has already been given in connection with the description of the cervical vertebrae. Early in the second month a centre of chondrification appears in the posterior part of the blastemal anlage of the occipital on each side of the median line (Fig. 308). Apparently a separate centre arises in the caudolateral (neural) process, but this very quickly fuses with the main parachordal centre, and it is possible that it is^. not always present. Each parachordal cartilage ext.end^ loijward at the side of the chorda dorsalis until the region is reached where the chorda dorsalis enters the dense retropharyngeal mesenchyme. Here the two parachordal plates fuse dorsal to the chorda into a single median plate which extends forward to the sphenoidal region (Fig. 266). At first the parachordal cartilages are separated from one another posteriorly by dense tissue (Fig. 266) and the median plate is similarly separated from the sphenoidal cartilage. Before the end of the second month, however, the posterior extremities of the parachordal cartilages become united ventral to the chorda and the median occipital plate becomes fused to the sphenoidal cartilage, at first laterally and then in the sagittal plane. The chorda dorsalis at this period runs in dense tissue in a dorsal groove in the occipital cartilage, then through this cartilage into the retropharyngeal tissue, thence dorsalwards in the line of suture between the occipital plate and the sphenoidal cartilage and terminates dorsal to the sphenoid cartilage (Fig. 266).

Laterally a cartilaginous process extends out in the blastema on each side of the hypoglossal nerve. The process caudal to this nerve, as above mentioned, apparently, at times at least, has a separate centre of chondrification, like the neural process of a spinal vertebra, but this becomes much more quickly fused with the body than does the latter. The apical lateral cartilaginous process is formed considerably later than the caudal.

The hypoglossal foramen is at first completed by blastemal tissue. In this tissue ventrolateral to the foramen there appears a separate centre of chondrification. The cartilage arising here soon becomes fused to the processes extending out from the median plate on each side of the hypoglossal nerve, thus completing the cartilaginous boundary of the foramen and the pars lateralis of the occipital cartilage. From it there extends in an apico-Tfentral direction, lateral to the jugular foramen, a prominent jugular process. The condyloid process is developed on the caudal side of the posterior lateral process of the occipital (Fig. 264, p. 344).

Chorda Dorsalis — The suboccipital portion of the chorda dorsalis becomes more and more irregular in form during the third month. Small processes are given off, some of which become separated from the chorda. In this region the chorda remains longest united to the pharyngeal epithelium. Some processes of the chorda are found, even in the second month, connected with processes of the pharyngeal epithelium. The connections are probably partly primary and partly secondary (Fig. 266). In the fourth month the chorda usually becomes discontinuous in places. After this it is gradually absorbed. During the chondrification of the basioccipital the chorda tissue is pressed back between the dorsal side of the occipital plate and the tip of the dens epistrophei. Chordomata may arise here.

The Labyrinth — While the semicircular canals are being differentiated the mass of tissue in which they are embedded becomes somewhat loose in texture and gradually from without medialwards becomes transformed into a peculiar kind of precartilage, the cells of which long remain nearer to one another than in most cartilage (Fig. 31D). The cochlear portion of the capsule becomes chondrified much later than the capsule of the canalicular part. The semicircular canals are lined by epithelium which abuts directly against the surrounding cartilage. The fibrous coat of the labyrinth is gradually differentiated from the cartilage. The oval and round foramens become distinct during the period of chondrification, because the tissue which covers them remains membranous while the surrounding tissue is converted into cartilage.

The capsule of the labyrinth is at first incomplete (Fig. 310). At the end of the second month the geniculate ganglion and the facial nerve lie in a slight groove on the vestibular portion of the capsule (Fig. 310), while the cochlear and vestibular ganglia extend into the large dorsal fissure between the canalicular and cochlear portions of the capsule. As development proceeds the anterolateral extremity of the dorsal edge of the cochlear portion of the capsule extends in a dorsolateral direction so as to cover the two auditory ganglia. At the same time the groove containing the geniculate ganglion and the neighboring portion of the facial nerve becomes converted into a canal (Fig. 313). The saccus endolymphaticus is not included in the otic capsule (Fig. 310). Lateral from the foramen endolymphaticum, in which the ductus endolymphaticus is enclosed, lies the fossa subarcuata (Fig. 313) in the human chondrocranium it is not deep. In the petrosa of children of from 2 to 10 years of age it is much deeper ; in adults it again becomes shallow (Mead).

Fig. 310. — Modd

Fig. 311. —

From the capsule of the labyrinth above the ossicles a process grows forward (P. perioticus superior Gradenigo) {Figs. 311, 312, 313). Ventrally this extends into a piate composed of fibrous connective tissue. This plate is connected with the pars cochlearis.

The tegmen tympani is formed from the cartilaginous process and the accompanying fibrous plate. The cartilaginous process is well shown in Fig. 313. Into the finer details of the development of the skeleton of the internal ear we cannot here enter. The cochlear portion of the capsule of the labyrinth is long connected by a fairly dense mesenchyme with the median plate of the occipital. After the chondrification of this portion of the capsule it becomes fused to the cartilage of the median plate, forming with it a continuous cartilaginous structure (Fig. 313). Across the jugular foramen somewhat irregular bars of cartilage may be formed (Fig. 313, right side).

In vertebrates below birds and nuumnals the auditory capsules lie in the lateral wall rather than in the floor of the cranial cavity. In man the basal position of the auditory capsules is more marked than in any of the lower mammals.

Tectum Postering — The cranial vault, as previously pointed out, is formed at first by a thin dense layer of membranous tissue, which is closely applied to the lateral side of the capsule of the labyrinth and extends ventrally into the dense tissue of the branchial region. Posteriorlj^ and inferiorly it is attached to the pars lateralis of the occipital. This membrane at first completes the f. jugulare. In the sixth week cartilage begins to extend into it from the posterior lateral (neural) process of the occipital. This cartilage extends as a flat band rapidly in an anterior direction in the membranous vault. In a 14 mm. embryo it has extended anteriorly above the otic region, but lies at some distance from the dorsolateral margin of the otic capsule. Soon after this it extends in a ventral direction so as to be closely applied to the otic capsule posteriorly and dorsally (Fig. 311), but even toward the end of the second month it is still distinctly separated from this by a narrow band of membranous tissue. Later the two become fused (Fig. 313). Between the capsule and the margin of the cartilaginous vault there are several apertures for the passage of bloodvessels.

During the third month the vault cartilages of each side extend dorsally and become united so as to complete a flat bridge of cartilage between the right and left occipitotemporal regions. This bridge of cartilage is called the tectum posterius or synoticum.

The description here given of the development of the tectum posterius differs in several respects from those of Levi, Bolk, and some other investigators. It is based on a study of several embryos between 11 and 20 mm. in length which the writer has had at his disposal. Possibly there are individual variations in the mode of the development of the tectum.

Levi describes a squama occipitalis which arises from a separate centre of chondrification, fuses with the pars lateralis of the occipital, and extends in an anterodorsal direction in the membranous vault; and a squama temporalis, which arises from a separate centre, fuses with the auditory capsule, and extends dorsally into the membranous vault (Fig. 309). The squama occipitalis and squama temporalis become fused and the temporal squama greatly reduced at the expense of the occipital squama. The occipital squamsB fuse to form the tectum posterius. according to Bolk, there is first formed a cartilaginous band, anterior interotic band, between the auditory capsules or the parietal plates applied to these. The posterior margin of this band extends into the membrana spinoso-occipitalis, which is attached laterally to the ear capsules and to the partes laterales of the occipital and posteriorly extends into the membrana reuniens dorsalis. Posterior to the interotic band of cartilage a second band is formed by outgrowth of cartilage from the partes laterales of the occipital and the caudal part of the otic capsule. This latter cartilaginous band is separated from the former by a membranous interval in which temporarily a pair of cartilages appear. There also appears in front of the anterior interotic band a temporary centre of chondrification. In the lower mammals there has frequently been described a cartilaginous lamina parietalis lying above the auditory capsule and united to the commissura orbitoparietalis.

Orbitotemporal Region

In man the cartilage of the orbitotemporal region, forms the basis for the ossification of the body, of the orbital and temporal wings, and of the laminae laterales of the processus pterygoidei of the sphenoid. These parts have special centres of chondrification which at first are separate but which fuse later. The chondrification of the body of the sphenoid begins in the median line anterior and ventral to the apical end of the chorda dorsalis in embryos between 12 and 13 mm. long. The position of this cartilage in a 14 mm. embryo is shown in Fig. 266. Prom this centre an arm of cartilage (Rathke's Schadelbalken) extends forward on each side of the hypophyseal pocket. In front of this the two processes unite to form the anterior part of the body of the sphenoid. In the lower vertebrates a pair of cartilages, trabeculae, are formed, one on each side of the hypophysis. These cartilages usually unite with one another apically and with the occipital parachordal cartilages caudally. It is a question whether or not these trabecul© are homologous with the sphenoidal cartilage above described (see Gaupp, 1906, p. 826). The caudal part of the body of the sphenoid becomes fused with the apical end of the median occipital plate and sends a process, the dorsum sellae, upward toward the midbrain fold. The apical end of the chorda comes to lie in the cartilage at the base of the dorsum sellae or between the cartilage and the perichondrium of the sella turcica or of the dorsum sellae. In the cartilage the chorda soon disappears; under the perichondrium it persists longer than elsewhere in the cranium and may give rise to chordomata (Williams). The cartilaginous body of the sphenoid gradually assumes the shape characteristic of the adult bone. During the third month the fossa hypophyseos, the tuberculum sellae, and the sulcus chiasmatis become fairly distinct (Fig. 313).

The hypophyseal canal is at first relatively large and is much broader than it is long. The tissue immediately about is very slowly converted into cartilage during the third month. occasionally a patent canal is found in the adult bone.

The cartilaginous ala temporalis (see Fig. 310) arises in the orbitotemporal blastema some distance below the membrane which forms the floor of the cranial cavity. It is only at a much later period that the temporal wing helps to bound the cranial cavity. During the latter half of the second month two portions may be distinguished in the ala temporalis, a medial and a lateral (Figs. 309 and 310).

The medial portion (processus alar is, Hannover) lies in the plane of the body of the sphenoid. It consists at first of blastemal tissue which extends from the body of the sphenoid opposite the hypophysis laterally and then posteriorly so as partially to enclose the internal carotid artery. It has a special centre of chondrification. It approaches closely but does not fuse with the otic capsule (30 mm. fetus). A closed foramen caroticum is found in several mammals, but is transitory when present, and probably is not constant in the human embryo (Levi).

The lateral part of the ala temporalis arises in a plane ventral to the medial part. The condensed blastema of which it is at first formed becomes fused to the ventral surface of the medial t

part near where this turns posteriorly about the internal carotid artery. The lateral part of the ala temporalis is small where it joins the medial part, but expands rapidly as it extends laterally, anterior to the otic capsule and ventral to the cranial border of the trigeminus ganglion. It has a separate centre of chondrification. The lateral part becomes cartilaginous later than the medial but becomes ossified much sooner (Fig. 313). From the ventral surface of the medial end of the lateral portion of the ala temporalis a short process extends ventralwards. This represents the anlage of the lateral lamella of the pterygoid process.

The ganglion of the trigeminus lies at first caudal to the lateral part of the ala temporalis, and the first and second branches of this nerve as well as the motor nerves of the eye pass forward medial to this process. During the period of chondrification the second branch of the trigeminus becomes enclosed in the foramen rotundum. The third division of the trigeminus at first passes down between the ala temporalis and the otic capsule. It later becomes embedded in a groove on the posterior margin of the ala temporalis. This groove is converted into the foramen ovale before or during the period of ossification. The foramen spinosum is similarly formed about the middle meningeal artery.

The ala orbitalis is differentiated from the orbitotemporal blastema first by condensation of tissue and then by chondrification. It is larger at first than the ala temporalis. In a 14 mm. embryo a blastemai process, the taenia metoptica of Gaupp, arises from the side of the body of the sphenoid, extends up behind the optic nerve and then over this into a plate of membranous tissue which forms the roof of the orbit and the floor of the cranial cavity. A second blastemai process, taenia preoptica, extendts from the side of the anterior extremity of the body of the sphenoid in front of the optic nerve laterally into the orbital plate. Chondrification (Fig. 310) appears first in the taenia metoptica in the region posterior to the optic nerve, and from here extends medialwards to fuse with the anterior part of the body of the sphenoid and lateralwards into the orbital plate (Fig. 313). The orbital plate has a separate centre of chondrification. The taenia preoptica apparently becomes chondrified through extension of cartilage into it from the body of the sphenoid. Chondrification begins later in this than in the taenia metoptica and the orbital plate. During the third month the ala orbitalis becomes fused into a single piece of cartilage and at the same time joined by bands of cartilage (cartilago spheno-ethmoidalis) to the lateral edge of the cribriform plate of the ethmoid (Fig. 313).

In many mammals the outer end of the ala orbitalis is connected with the cartilage of the cranial vault dorsal to the otic capsule (parietal plate) by a bridge of cartilage, the commissura orbitoparietalis (Gaupp). This bridge, which is lacking in man, encloses a large (sphenoparietal) foramen.

Ethmoroal Region and the Nasal Capsule

Fig. 311. —

The ethmoidal region and the nasal capsule are the last portions of the chondrocranium to become cartilaginous. In an embryo 20 mm. long and in the eighth week of development (Figs. 310 and 311) the tissue is still membranous, although both the nasal septum and the lateral wall of the nasal capsule are evidently in a precartilaginous stage. In the third month the cartilaginous capsule is extensively developed (Figs. 312 and 313).

The chondrification of the septum apparently takes place by anterior extension from the cartilage of the ventral part of the body of the sphenoid. The septum is at first relatively thick, especially on the ventral margin. From the anterior part of this thickened ventral margin of the septum a **paraseptal" cartilage becomes isolated on each side (third month).

In many of the lower mammals the anterior part of the ventral margin of the septum becomes joined to the lateral wall by a band of cartilage, the lamina transversalis anterior, thus separating the " fossa narina " from the " fenestra basilaris." The paraseptal cartilage in these mammals extends from the posterior margin of the lamina transversalis anterior into the fenestra basilaris. In man the lamina is not developed, so that a long fissura rostroventralis is present in the nasal capsule. The paraseptal cartilage primitively in mammals, but not in the repliles, furms a sheath for Jaccbson's organ, but in mao it has lost this function. It, however, persists until after birth (E. Schmidt). according to Mihalkovics, several isolated pieces of cartilage found in the third month lateral to the inferior margin of the nasal septum may indicate rudiments of the L, transversalis anterior.

Fig. 312. —

Fig. 313. — (After Hertwig's model, from Kollman Handatlas, 1907, Fig. 266) Visceral skeleton of the labyrinth of a human fetus at the end of the third month (8 cm long).

Posteriorly the cartilage of the nasal septum is much narrower than it is anteriorly. It does not extend into the blastemal septum between the nasopharyngeal passages.

The chondrtfication of the lateral walls (C. paranasalis) of the Dasal fossa; seems to take place independently, but the lateral cartilage is soon joined to the nasal septum, anteriorly forming the cartilaginous roof and sides of the nose, tectum nasi, and paries nasi, and somewhat later it is posteriorly united to the region where the sphenoidal cartilage passes over into the cartilage of the septum. Through infolding of its inferior margin the lateral wall of the nasal fossa posterior to the narina nasi furnishes the anlage of the maxillary turbinate, concha inferior. This is at first simple in form though later more complicated. Late in the third month it develops an accessory process curved upwards, and in the fifth month exhibits extensive folds (Mihalkovics). It becomes separated from the lateral wall when the latter undergoes retrograde metamorphosis (seventh month, Killian).

During the blastemal period folds in the surrounding mesenchyme project into the nasal fossa. On the posterior dorsal part of the lateral wall there is formed a fold of tissue which, according to Peter (1902), may be looked upon as having been derived from the caudodorsal part of the median wall. This fold gives rise to the anlage of the middle turbinate, concha media. The anlage of the superior turbinate arises in a manner similar to the middle. Following this there are formed much later the anlages of three more turbinate processes. Thus there are five chief ethmoidoturbinate processes in addition to the maxilloturbinate already described. Apiealwards, between the concha media and the concha inferior, there appears a rudimentary nasoturbinate which gives rise to the agger nasi and the uncinate process. (See Killian, 1895, 1896; Peter, 1902.)

Besides the chief turbinates there are numerous accessory turbinates. The bulla ethmoidalis arises from accessory processes in the meatus beneath the middle turbinate. The complicated changes which take place in the nasal turbinates cannot be entered upon in detail in this section.^

Chondrification of the ethmoidal turbinates, of the uncinate process, and of the bulla ethmoidalis begins in the fourth month.

The cartilaginous capsule of the nose at first is open toward the olfactory bulb, but during the third month the cribriform plate is formed by chondrification of tissue between various nerve bundles (Fig. 313). The lamina cribrosa is characteristic of mammals, but is not present in all.

In most of the lower mammals the caudal margin and the caudal part of the inferior margin of the lateral wall of the nasal capsule bend towards the nasal septum and then forwards so as to bound a cupola-shaped recess (the sinus terminalis) at the caudodorsal extremity of the nasal fossa. In man this recess, the anlage of the sinus sphenoidalis of the osseous cranium, is not much developed and has no ventral cartilaginous wall. A membranous septum is, however, formed between the meatus nasopharyngeus and the cupola-shaped recess. The septum becomes ossified, forming the floor of the sphenoidal sinus. The paranasal cartilage bounds the recess laterally, but does not bound the meatus nasopharyngeus. The latter becomes bounded laterally by a membrane bone (os pterygoideum).

In the third to fourth month a short cartilaginous process (proc. paranasalis) arises from the lateral wall of the nasal capsule and encircles the lachrymal duct.

The fate of the cartilaginous nasal capsule is varied. Parts become ossified, parts are converted into connective tissue or disappear, and parts pass over into the cartilaginous portion of the skeleton of the adult nose. The greater part of the posterior portion of the capsule becomes ossified as the ethmoid bone. The dome-shaped wall of the sinus terminalis gives the basis for the concha sphenoidale (ossiculum Bertini). The maxilloturbinate (concha inferior) and a part of the nasal septum likewise become ossified. Parts of the septum and of the inferior portion of the lateral wall above the maxilloturbinate, however, disappear and are replaced by parts of the neighboring membrane bones. The cart, paraseptalis remains till after birth. A large part of the septum and parts of the roof of the nose remain cartilaginous throughout life. The C. alares majores become separated by development of connective tissue from the rest of the nasal capsule during the fourth to fifth month of intra-uterine life. The C. alares minores and the C. sesamoidia; are differentiated from the C. atares majores. The cartilago spheno-ethmoidalis, the orbital wing of the cartilaginous ethmoid, which during the third month extends as a broad plate between the lateral margin of the lamina crlbrosa of the ethmoid and the ala orbitalis of the sphenoid (Fig. 313), in the fourth to fifth month is broken up into several pieces and absorbed.

- See the description of the development of the nose in the section on the organs of special sense.

u, 1907. Fi(. 366.J VisMnl skeleton of the tuB 8 cm. long.

Derivatives of the Visceral Arches

From the visceral arches are derived the bones of the middle ear, the styloid process of the temporal bone, the stylohyoid ligament, the hyoid bone, and the cartilago thyroidea. In the human embryo the formation of the blastemal ossicles and of the hyoid bone is a fairly direct process, but their relations to the embryonic skeleton of the mandibular and hyoid arches (Meckel's and Reichert's cartilages) are more or less clearly marked. The relations of the laryngeal cartilages to the visceral arches are not so definite.

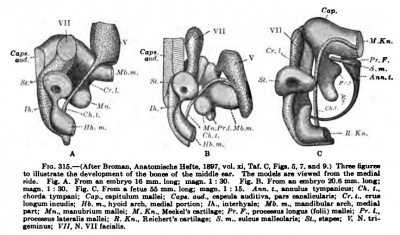

Toward Uie end of the first month the tissne in the branchial arches, in the lateral region of the head immediately dorsal to these, and about the larynx becomes much condensed. according to I. Broman, the tissue in the dorsal part of the mandibular arch region is divided by the third division of the fifth nerve into lateral and medial portions, while that in the hyoid arch region is similarly divided by the seventh nerve. The relations of these divisions of the blastema of the first two arch regions to the auditory ossicles are described as follows:

The proximal portion of the lateral part of the blastema of the mandibular arch region gives rise to the anlage of the incus. From this in a 14 mm. embryo a process of condensed tissue may be followed anteriorly, lateral to the fifth nerve, into the anlage of the maxilla. This later disappears. The anlage of the incus soon fuses with the blastema of the otic capsule {Fig. 315, A), but becomes separated again at the time of chondrification. The proximal part of the lateral division of the blastema of the hyoid arch region gives rise to the anlage of the tympanohyale (laterohyale). This in turn becomes fused to the capsula auditiva and to the styloid process (Fig. 311).

Fig. 315. — (After Bronuo. AnmtomiKhc Hefte. 1897. vol.)

The cartilage of the external ear is differentiated from the blastema of the dorsolateral region of both the mandibular and the hyoid arches.

The proximal end of the medial part of the blastema of the mandibular arch region is checked in development by the vena jugularis primitiva. The portion beyond this gives rise to the anlage of the malleus (Fig. 311), and this is continued into a condensed band of tissue that may be followed in the mandibular arch to the mid-ventral line. This band is the anlage of Meckel's cartilage and appears in an embryo 11 mm. long as a rod of dense tissue.

The proximal end of the medial part of the blastema of the hyoid arch region gives rise to the anlage of the stapes (Fig. 311). 21 This anlage is from the first connected by a band of blastemal tissue with the anlage of the incus. The band of tissue develops into the crus longum incudis (Fig. 315, C).

Immediately ventral to the anlage of the stapes there is formed a small band of tissue (interhyale, Broman; lig. hyostapediale, Fuchs), which connects this anlage with the main hyoid arch. It lies beneath the facial nerve (Fig. 315, A and B). It forms a partial sheath for this nerve. In the second month it disappears, so that the stapes anlage is no longer connected with the main hyoid scleroblastema. The latter is a rod-like process which extends from the tympanohyale (laterohyale) medialwards to the anlage of the body of the hyoid bone. It is visible in an 11 mm. embryo.^^ It gives rise to the styloid process, the stylohyoid ligament, and the lesser comu of the hyoid bone.

It is convenient to consider the development of the ossicles and of Meckel's cartilage separately from the development of the hyoid bone, the styloid process, and the laryngeal cartilages.

The Ossicles and Meckel's Cartilage

During the latter half of the second month Meckel's cartilage becomes chondrified. Its position at this period is shown in Fig. 311. It does not reach quite to the midventral line. Later it sends a process upwards parallel to the medial line (see Figs. 312-324).

Dorsally Meckel's cartilage is continued into the capitulum of the malleus (Figs. 311, 314, 315, B and C).^* Toward the end of the second month the malleus is fairly well differentiated (Figs. 311 and 315, B). The manubrium extends medialwards in a dense mass of tissue which intervenes between latter arises, according to Fuchs, from a centre which lies in the region where the temporo-mandibular joint is later differentiated, and from which the articular part of the squamosum also arises. according to Fuchs, the mandibular joint of mammals is homologous with the quadrato-articular joint of the lower forms. according to most investigators, the quadra to-articular joint is homologous with the malleus-incus joint in mammals, a view originally advanced by Reichert. See Gaupp (1906), Van Kampen (1905), Mead (1909).

- according to Hugo Fuchs (1905), in the rabbit the anlage of the stapes lies dorsal and anterior to the hyoid arch region and arises not in connection with the hyoid arch but rather in connection with the otic capsule. There is later formed a temporary connection between the anlage of the stapes and that of the skeleton of the hyoid arch, the " ligamentum hyo-stapediale."

- according to Fuchs (1905), in the rabbit the anlage of the erus longum of the incus arises apparently independently of the main anlage of the incus.

- according to Fuchs (1905), in the rabbit it first appears in the region of the hyoid bone and thence extends dorsalward.

- According to Fuchs (1905), there is a common malleus-incus anlage in the rabbit, which arises independently, chondrifies from a separate centre, and becomes secondarily fused to Meckel's cartilage. The

the lateral extremity of the tubotympanic cavity and the medial end of the external auditory meatus.

In Fig. 311 the most medial part of this tissue and the medial extremity of the external auditory meatus are shown. From the manubrium a ** lateral" process is at first directed downwards. As development proceeds the manubrium comes to be directed downwards and the lateral process is turned outwards. The crista mallei arises during the fourth month. It is not due to the outgrowth of a process, but rather to absorption of the underlying cartilage. The joint surfaces between the malleus and incus have from the first two chief facets, as in the adult. The greater facet is at first directed laterally, the smaller dorsally. When rotation takes place the greater facet faces dorsally, the smaller medially. At the beginning of the third month the accessory facets of the joint surface and the **Sperrzahn" of Helmholtz appear. The cartilaginous malleus is at first joined to the cartilaginous incus by dense tissue, in which later a joint cavity arises.

The incus (Figs. 311, 314, and 315, B and C) becomes chondrified during the latter half of the second month. It has a special centre of chondrification, which first appears in the head and then extends to the processes. The head at this period is embedded in dense membranous tissue (Fig. 310).

Cartilage extends into the cms longum as far as the joint between it and the stapes. This joint is at first composed of dense tissue but is later differentiated into a true joint. The cms brevis is formed when chondrification starts in the anlage of the incus. At this p)eriod the head of the incus becomes somewhat separated from the capsule of the labyrinth, with which it has been temporarily fused. A short blastemal process is left which extends dorsally from the incus to the capsule. Into this process the cartilaginous cms breve extends. In Fig. 311 the space between the cms breve and the auditory capsule is shown slightly too wide in order to reveal the deeper structures. The processus lenticularis is not formed until the crus longum has begun to ossify. At the beginning of the third month the crus breve, cms longum, and the manubrium of the malleus lie nearly in a plane, a condition noted by Helmholtz in the adult. The malleus and Meckel's cartilage are homologous with the skeleton of the lower jaw in the inferior vertebrates. The incus is homologous with the quadrate portion of the palato-quadrate. The palate portion is not represented.

The first definite differentiation of the stapes is seen when the cells of the anlage form a ring of tissue concentrically arranged about the stapedius artery. This is at first separated from the capsule of the labyrinth by loose tissue, but later becomes fused to it, although still distinguishable by the arrangement of the cells. When chondrification sets in, it becomes still more clearly marked oflF. From the first it has an oblique position (about 45^ to the horizon). Chondrification begins during the latter part of the second month. At the end of the third month the hitherto circular stapes begins to take its definite form. The artery persists to the end of the third month. As the foot-plate of liie stapes becomes differentiated the lamina fenestris ovalis becomes thin.

- according to Fuchs (1905), in the rabbit the manubrium arises separately from the anlage of the head of the malleus, to which it extends from the hyoid arch region.

Tympanohyale, Reichert's Cartilage, the Hyoid Bone, and the Laryngeal Cartilages

The tympanohyale (laterohyale) arises from the proximal part of the lateral blastema of the hyoid arch region. It becomes chondrified from a separate centre and then proximally fuses to the cartilaginous otic capsule, while distally it becomes fused with the chief cartilage of the hyoid arch. The part of the otic capsule with which the tympanohyale fuses is a process that lies on the ventrolateral ^nrface of the promontory of the lateral semicircular canal, the crista parotica. The processus perioticus superior is developed at the apical end of this crest. The proximal end of the tympanohyale is enclosed in the tympanic cavity and utilized in the formation of the wall of a canal containing the nervus facialis, the musculus stapedius, and a few blood-vessels (foramen stylomastoideum primitivum, Broman).

The chief blastemal skeletal element of the hyoid arch is a rod of tissue which is proximally connected both with the anlage of the stapes and with that of the tympanohyale. Distally it extends to the lateral margin of the anlage of the body of the hyoid bone. It loses its proximal connection with the stapes, becomes chondrified from a separate centre and finally fused with the distal end of the cartilaginous tympanohyale (Figs. 311, 314). It is now known as Reichert's cartilage. Subsequently it becomes transformed into the lesser cornu of the hyoid, the stylohyoid ligament, and the styloid process.

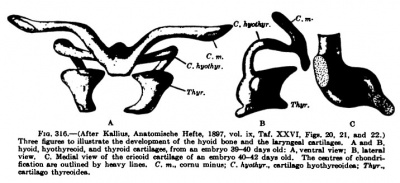

It has been pointed out above that the mesenchyme of the visceral arches toward the end of the first month becomes verv dense and that a dense mass of tissue surrounds the anlage of the larynx. This mass of tissue is especially developed ventral and lateral to the larynx and is connected with the dense blastema of the hyoid and of the more posterior visceral arches. During the second month there are developed in this tissue the anlages of the body and of the greater cornua of the hyoid bone and of the laminsB and the cornua of the thyroid cartilage of the larynx.

The appearance of the structures mentioned above toward the end of the second month is shown in Fig. 311. Their appearance about the middle of the second month is shown in Fig. 316.

The body of the hyoid is developed from the ventral part of this dense tissue in front of the proximal end of the larynx. It may be barely distinguished in an 11 mm. embryo. Pl-ecartilage appears in it in a 14 mm. embryo. At about this time it has the form shown in Fig. 316, A and B. The form is essentially similar at the end of the second month (Fig. 311), but it is still composed largely of dense tissue and precartilage. During the third month it becomes more highly differentiated. The body of the hyoid bone probably represents a copula of a visceral arch or the fusion of two such copulaB. Kalliiis found in the cow an anterior and a posterior anlage, the former of which may represent a hyoid, the latter a third visceral arch copula. No such double anlage has been found in man.

- See, however, note 24, p. 419, and note 43, p. 141.

Fig. 316. — (After Kallius, Anatomische Hefte. 1897, vol. ix, Taf. XXVI, Figs. 20, 21, and 22.) Three figures to illustrate the development of the hyoid bone and the laryngeal cartilages. A and B. hyoid, hyothyreoid, and thyroid cartilages, from an embr3ro 39-40 days old: A, ventral view; B. lateral view. C. Medial view of the cricoid cartilage of an embryo 40-42 days old. The ceotra of chondrification are outlined by heavy lines. C. m., comu minus; C. hyothyr., cartilago byothyreoidea; Thyr^ cartilago thyreoidea.

The anlage of Reichert's cartilage in the 11 mm embryo above mentioned is more highly developed than the body of the hyoid. It is composed of a very dense tissue, which is connected with the blastema of the body. When chondrification takes place Reichert 's cartilage long remains separated from the cartilage of the body of the hyoid by a narrow band of dense tissue which forms a kind of primitive joint. Finally the two cartilages become fused.

Between the body of the hyoid bone and the laminae of the thyroid cartilage in the dense tissue lateral to the larynx there is developed a curved cartilaginous bar, which we may call the hyothyroid cartilage (Figs. 311, 316, A and B). Ventrally this bar is joined at first by dense tissue, later by cartilage, to the back of the body of the hyoid. Dorsally it becomes fused to the cartilage of the lamina of the thyroid. It is invisible in an embryo of 11 mm. and becomes chondrified apparently from a single centre at about the time of the chondrification of Reichert's cartilage. It represents the skeleton of the third and a part of the fourth visceral arches. Its ventral portion becomes the greater cornu of the hyoid bone and its dorsal inferior portion the superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage. The two portions become discontinuous at the end of the third month, so that a small cartilago triticea is separated on the one side from the great cornu of the hyoid bone and on the other from the superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage. Connective tissue serves at the same time to form connecting ligaments, but the definite lig. hyothyroideum is not well developed until after birth, when the hyoid bone becomes further separated from the thyroid cartilage.

The blastemal laminae of the thyroid cartilage appear about the middle of the second month. One appears on each side at the p)eriphery of the dense tissue surrounding the ventral part of the larynx. This anlage has the form of a slightly curved quadrilateral plate in which a foramen may be seen (Fig. 316, B). There are two centres of chondrification, one cranial and the other caudal to the foramen. The cranial centre is continuous with the hvothjToid cartilage and later becomes united on each side of the foramen to the cartilage of the caudal centre. The foramen is usually closed by cartilage, but occasionally remains patent throughout life. The inferior cornu is developed from the dorsal part of the caudal margin of the lamina. Ventrally the laminae of each side become united by the membranous tissue into which the cartilages of the cranial and caudal margins of the laminae extend, and finalljr unite in the mid-ventral line. Between the two margins there is an orifice closed merely by membrane. In this a special centre of chondrification appears. This medial cartilage eventually becomes united to the cartilage of the laminae, so that the central orifice is closed in the tenth to thirteenth week (according to Kallius). The cranial margin of the thyroid cartilage is at first nearly level. The incisura arises through the rapid development of the laminae lateral to the median line. The cornu inferius, the tuberculum superius and inferius, and the linea obliqua are developed during the latter part of the fourth month.

The thyroid cartilage is supposed to be derived from the fourth and fifth visceral arches. The central cartilage probably represents copulae.

The cricoid cartilage is the first of the cartilages of the larynx to show definite hyaline tissue. About the lower part of the larynx there is formed a dense band of tissue. In this tissue a semicircular cartilaginous process appears. (In Fig. 316, C, the cartilage is surrounded by dark lines.) It is bilaterally better developed than in the mid-line, but if there are two bilaterally placed centres these quickly fuse ventrally. The cartilage slowly develops in the dorsal direction. Fig. 311 shows it at the end of the second month. In the third month the ring is completed and the posterior lamina is developed.

The arjiiSBnoid cartilage develops from the blastema continued cranialward from the cricoid cartilage (Fig. 316, C). A special centre of chondrification appears in the seventh week. The first part of the cartilage developed represents the posterior portion, chiefly the proc. muscularis. From this the processus vocalis grows ventrally. This process, however, is long blastemal and does not reach its definitive form till the end of the fourth month (Kallius). The apex of the cartilage grows cranialwards, so that the definitive form of the cartilage, with the exception of the proc. vocalis, is approached by the end of the third month. There is regularly present in later fetal life on the arytaenoid cartilage ventral to the cart, comiculata a process which disappears after birth. Its place is marked by the origin of the ligament which extends to the cartilago cuneiformis. It is probable that it represents the cartilaginous process which connects the arytaenoid and cuneiform cartilages in some animals (Kallius).

The blastemal anlage of the cart, corniculata is continuous with that of the cart, arytaenoidea. Toward the end of the third month it chondrifies from a special centre. The cartilage of the epiglottis does not appear until the end of the fifth month. It has a single median centre.

The cuneiform cartilages develop in the blastema of the plicaB aryepiglotticsB. They appear toward the end of the seventh or early in the eighth month.

Period of Ossification.

In the human skull the membrane bones are extensively developed, compared with those in lower forms. Some of the centres of ossification in the membranous tissue arise before any of the centres in cartilage. Thus Mall (1906) has found centres of ossification for the mandible (39th day), maxilla (39th day) and premaxilla (42d day), before any centre of ossification has appeared in the chondrocranium. The first centres of ossification to appear in the chondrocranium are those in the occipitale laterale (56th day), the basioccipital (65th day), orbitosphenoid (83d day), and basisphenoid (83d day).

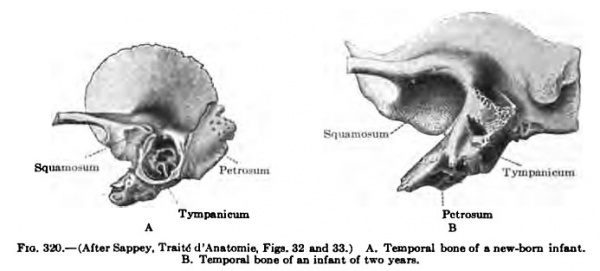

The complexity of tiie ossification of the bones of the skull makes it advisable to discuss briefly the development of each of the iudividnal bones recognized in the hnman skull rather than to treat of the bones in classified groups. Most of the bones of the human skull arise from two or more centres of ossification, some of which represent individual bones in the lower vertebrates.

Occipitale

In the occipital bone five elementary parts may be distinguished, a basal (basioccipital), two condylar (oecipitalia lateralia, exoccipitals), an occipitale superius (squama, inferior part), and an interparietal (squama, superior part). The interparietal arises in membranous tissue, the other parts in cartilage.

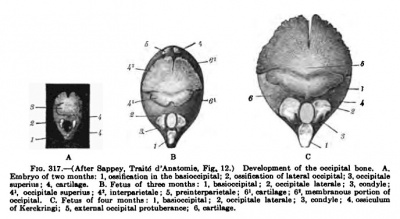

Fig. 317. —

The basioccipital and the two oecipitalia lateralia arise each from a separate centre of ossification in the ehondrocranium, and at birth are still separated from one another by cartilage (iPig. 317, A, B, C). The centres for the oecipitalia lateralia appear on the 56th day and that for the basioccipital on the 65th (Mall).

The occipitale superius and the interparietal are at birth fused into a single plate of bone.^ The occipitale superius arises from four, the interparietal from two centres of ossification (Mall). according to Mall, the first centres of ossification to appear are two bilaterally placed centres for the occipitale superius which arise in the cartilage immediately dorsal to the foramen magnum (55th-56th day). These two centres soon imite across the midline,^® and are joined by two secondary centres, one of which arises on each side. occasionally an additional unpaired median centre appears on the dorsal margin of the foramen magnum.^ More often, however, there arises a small process, on the inferior margin of the squama in the medial line (Fig. 317, C, 4). This process, later enclosed by bone, gives origin to the crista occipitalis interna (Lengnick, 1898).

The two bilaterally placed interparietal centres appear on the 57th day in the membranous tissue which extends anteriorly from the occipitale superius. They are rectangular in form and unite on the 58th day to form the interparietal bone. The interparietal unites with the occipitale superius in the first half of the third month of intra-uterine life to form the squama of the occipital. Fusion takes place in the median line before it does laterally ; at birth the lateral fusion is usually incomplete. The interparietal may remain partially or wholly separated from the occipitale superius throughout life. In many of the lower manmials the interparietal normally remains distinct from the supraoccipital. according to Ranke, the squama occipitalis arises from four pairs of centres of ossification. Various investigators diifer considerably in the number of centres which they ascribe to this part of the occipital. Anterior to the interparietals a pair of pre-interparietal bones (Fig. 317, B) are apparently not infrequent. The osseous union of the occipitale superius and the occipitalia lateralia begins in the first or second year and is completed in the second to fourth year; that of the basioccipital and the occipitalia lateralia begins in the third or fourth but is not completed until the fifth or sixth year or later. The basioccipital forms the anterior fourth or fifth of the condyles. Some authors describe condylar epiphyses. The basioccipital is united to the basisphenoid by cartilage up to about the twentieth year (16th to 20th, Toldt). Ossific union is completed one or two years later (Quain's Anatomy, 10th ed.). Epiphyseal discs like those which complete the bodies of the vertebrae are described as arising and fusing with the contiguous surfaces of the basisphenoid and basioccipital before the two bones become united by synostosis. At the centre of the synostosis a mass of fibrocartilage frequently long persists. Remnants of the chorda dorsalis may likewise persist here and give rise to tumors. (See Poirier, Virchow, Welcker, Luschka, Steiner.)

- By some authors the bone here called occipitale superius is designated infraoccipital; and the bone here called interparietal is called supra-occipital. {See Poirier, Traite d'Anatomie, vol. i, p. 408-109,)

- according to Toldt, instead of two there may be a single medially placed centre. according to Bolk (1903), the ossification arises in the membranous part of the tectum synoticum.

- Ossiculum Kerckringii, Kerckring, 1670, Manubrium ossis occipitalis, R. Virchow. Ranke showed that it arises in cartilage and membranous tissue. Bolk found in one instance an independent cartilaginous nucleus in this region.

Considerable variation is found at the base of the occipital bone. {See Swjetscbnikow, 1906, p. 155.) Variations of this kind are associated with variations of the atlas.

Os Sphenoidale

In man the sphenoid bone arises chiefly from ossification centres which appear in the orbitotemporal region of the chondrocranium. To it several hones of membranous origin become fused. In the sphenoid one may distinguish fourteen centres of ossification: four in the basisphenoid, two presphenoid, two alisphenoid, two orbitosphenoid, two pterygoid, and two intertemporal. In

•t Auitomy. lOUi edn vol. il. Pt. I. Tig. TS.> Ostification of sphenoid ID early period, seen from above: I, the als temporalea oeeified; 2, the alie ion hu rncireled Ibo optic Fommen. ukd a miall luture is diitiDguishable at 3, nuclei of basisphenoid. B. Back part of the boae shown in A: *. mediaJ . C. ICopied from Heckd, Archiv. vol. i, lab. vi, Fig. 23i, and stated to be 4. Duclai ot piesphenoid; 5, separate lateral proceeaea of the body (UngulKl:

ined to the baaiapbeaoid and the medial plerygoid plalca (not ecen in the addition to these centres there are several in the ossicula Bertini which in part fuse with the presphenoid after birth. (See below.)

In each of the greater icings, alisphenoids, a centre of ossifica^ tion appears toward the end of the second month in the chondrocranium between the maxillary and the mandibular nerves. From this centre ossification extends into the lateral lamina of the pterygoid and into the lateral portion of the greater wing (Figs. 322 and 318, A and C). From the main centre a lamella of bone is usually formed about the mandibular branch of the trigeminal ner\'e, thus separating a foramen ovale from the foramen lacerum. according to some authors, there are two centres of ossification in the alisphenoid and external pterygoid which fuse together at an early period (Sappey).

In the latter part of the third month (Mall) a bilaterally placed pair of centres appears in the basisphenoid (Fig. 322 and Fig. 318, A). The two centres unite in the fourth month. After this union two other centres arise (sphenotics, Sutton, 1885), give origin to the lingulae, and fuse with the body (Fig. 318, C). The superior margin of the alisphenoid is strengthened by a membranous bone (Hannover, 1880). This bone, called the os intertemporale by Ranke, occasionally persists as an independent structure or may be fused to the squama temporalis or to the frontalis.

The nuclei for the medial pterygoid plates appear in the second month (57th day. Mall) (Fig. 318, B). They fuse with the nuclei of the greater wings in the fourth month. They are said to arise in cartilage, which develops in membranous tissue independent of the chondrocranium (Hannover, Graf v. Spee). according to Fawcett (1905), however, the main part of the medial pterygoid plate is ossified in membrane, although the hamulus is transformed into cartilage before ossification. according to Gaupp, there is questionable propriety in applying the term os pterygoideum to the lamina medialis if thereby one would imply homology with the os pterygoideum of reptiles. One should probably homologize it with the lateral part of the parasphenoid.

Each of the lesser wings, orbitosphenoids, is ossified from a centre which appears in the ninth week lateral to the optic foramen (Fig. 318, C). On the medial side of each optic foramen a centre of ossification, presphenoid, appears early in the third month (Fig. j 318, C). The centre for the orbital wing fuses with the corresponding presphenoid centre in the fourth month. The two presphenoid centres fuse with one another in the eighth month. acccording to Hannover (Gaupp, 1906), there are four presphenoid centres. Toldt and Sutton describe but two.

The presphenoidal centres become partially united to the ba sisphenoids in the seventh or eighth month. At birth, however, there is a ventral wedge of cartilage between the two portions of the bone. This does not disappear till late in childhood.^^ The greater wings become joined to the body of the sphenoid during the first year after birth. The base of the great wing spreads out over the side of the body of the sphenoid. Between it and the presphenoid there may be formed a small canalis craniopharyngeus lateralis (Sternberg, 1890). occasionally the hypophyseal canal persists as a canalis craniopharjTigeus medius.

The posterior end of the nasal septum (crista sphenoidalis and rostrum sphenoidale) is ossified by extension of bone from the presphenoid.

The concha sphenoidalis (ossiculum Bertini) arises through ossification of the posterior cupola (Kuppel) of the cartilaginous uasal capsule (see p. 416). Ossification begins in the fifth intrauterine month in the medial (paraseptal) wall of the cupola, and in the seventh to eighth month a secondary centre arises in the lateral wall. In the membranous floor of the cupola toward the end of intra-uterine life further centres of ossification arise and fuse with the bone originating in the two primary centres. By the third year each terminal nasal sinus is surrounded by bone except toward the nasal fossa, where an opening called the "sphenoidal foramen" persists. Each bone lies on the inferior surface of the presphenoid, lateral to the crista aphenoidalis and the rostrum sphenoidale, to which it is united by connective tissue. About the fourth year the superior and medial parts of the capsule begin to be absorbed, so that the presphenoid comes to bound the sinus terminalis. Laterally absorption of the bony capsule also takes place while the inferior portion and that surrounding the sphenoidal foramen become fused with the ethmoid. In the ninth to twelfth year, however, this portion fuses with the sphenoid and the sinus terminalis extends into the body of the latter (Gaupp, 1906; Cleland, 1863; Toldt, 1882).

- In many mammals the sphenoid remains permanently divided into two parts, a presphenoid, which comprises the apical end of the body and the lesser wings, and a postsphenoid, which comprises the sella turcica, the great wings, and the pterygoid processes.

Os Ethmoidale

The ethmoid bone arises from one medial and two lateral primary and from several secondary centres in the cartilaginous nasal capsule. The ossification of the posterior cupola of the cartilaginous nasal capsule in man as the ossiculum Bertini has been described in connection with the sphenoid bone. In the quadrupeds this portion of the nasal capsule is ossified in conjunction with the ethmoid (Gaupp, 1906). ub^iUS In each lateral wall of the nasal capsule a centre appears in the fifth to sixth fetal month. It gives rise to the lamina papyracea, and in the eartiiaginoui.i seventh and eighth months ossification „Renault. f torn Poiri«f.Poiner«.dCharpy, extends into the conchse and the lamT™wd'AnBunnie. voi.i. Fig.402.) o»iina eribrosa. The ethmoidal cells are closed off by folds of mucous membrane which arise in the latter half of fetal life and extend between the lamina cribrosa and the upper concha and betweenthe concha (Fig. 319). Into these folds of mucous membrane ossification extends from the concbie so as to give rise to osseous walls for the ethmoidal cells.

Ossification begins late in the first year^^ independently in the superior portion of the nasal septum (lamina perpendicularis). It extends into the crista galli, the cribriform plate, and the lamina perpendicularis. Sappey and Poirier, following Rambaud and Renault, describe several centres on each side of the upper margin of the lamina perpendicularis at the base of the crista galli. From these centres ossification extends successively to the crista galli, the lamina cribrosa, and the lamina perpendicularis. In the crista galli in the second year a secondary nucleus arises. Ossification of the process is not completed before the fourth year. In the second year two accessory nuclei appear in the anterior part of the lamina cribrosa. By the sixth year the lateral parts of the ethmoid become united to the medial part (v. Spee and most authors). ^^ Ossification of the ethmoid is not completed until the sixteenth year. Synchondrosis exists between the lamina cribrosa and the sphenoid until toward puberty. About the fortieth to forty-fifth year the lamina perpendicularis becomes united to the vomer.

Concha Inferior

This arises in cartilage from a separate centre of ossification which appears in the latter half of fetal life (seventh month, Toldt; fifth month, Quain, Graf v. Spee).

- according to v. Spee, before birth.

Vomer

The vomer arises from a bilaterally placed pair of nuclei which appear during the eighth week (Quain, Mali), near the back of the inferior margin of the cartilaginous nasal septum. These centres unite beneath the inferior margin of the septum, but superiorly they extend on each side of the nasal septum so as to enclose the cartilaginous septum between two thin plates of bone. The two plates of bone gradually become coalesced from behind forwards. Union is completed about the age of puberty (Quain). On the anterior and superior margins a permanent groove remains for the attachment to the lamina perpendicularis ossis ethmoidalis and the cartilago septi nasi. Although the vomer develops on each side of the cartilaginous nasal septum and at its expense, it is regarded as a true membrane bone.

The lamina cribrosa ossifies in part through extension of ossification from the crista gnWi and from the lateral ossific centres and in part from accessory centres. according to Sappey, Poirier, Toldt, and some other authors, the central part of the ethmoid becomes united to the lateral parts through ossification in the lamina cribrosa at the end of the first or in the second year.

"Third or fourth month after birth (Sappey, Testut, Poirier).

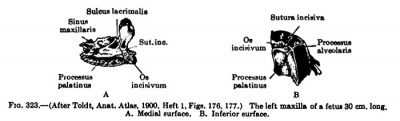

Os Palatinum