Book - Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930): Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

! Online Editor | ! Online Editor | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Mark_Hill.jpg|90px|left]] This is a draft version of McMurrich's 1930 anatomy history textbook on Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). | | [[File:Mark_Hill.jpg|90px|left]] This is a draft version of McMurrich's 1930 anatomy history textbook on Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). Note the images online have been adjusted from the original scan versions, in the file history, the first uploaded version is always the original. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[[Media:1930 Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist.pdf|PDF | [[Media:1930 Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist.pdf|PDF]] | [https://archive.org/details/leonardodavinciaOOmcmu Internet Archive] | ||

<br><br> | |||

See also: {{#pmid:31295863}} | |||

<br><br> | |||

{| class="wikitable mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" | |||

! McMurrich 1913 Book Review - Quaderni d' Anatomia | |||

|- | |||

| [[Anatomical Record 7 (1913)|Anatomical Record 7]] No. 4. April (1913) | |||

Book Review — J. P. McMurrich. Leonardo da Vinci Quaderni d' Anatomia. Parts I and II | |||

Leonardo da Vinci Quaderni d'Anatomia. | |||

Edited by Ove C. L. Vangensten, A. Fonahn and H. Hopstock. Parts I and II, Jacob Dybwad, Christiania, 1912. | |||

It has long been known, from statements made by Vasari, that Leonardo da Vinci had contemplated the writing of a book on Human Anatomy and had made for its illustration numerous drawings from dissections prepared by his own hand. On his death these drawings and the notes that accompanied them passed into the hands of a Milanese gentleman, Francesco da Melzi, but thereafter their history becomes obscure. During the reign of George III Dalton, who was at that time in charge of the Royal Library at Windsor, chanced upon a number of sheets covered with anatomical sketches and notes by Leonardo, which were apparently the manuscripts mentioned by Vasari. Investigation showed that they had been presented to Charles II, probably by the then Earl of Arundel, who had been Ambassador to the court of the Emperor Ferdinand II of the Holy Roman Empire, and having been deposited by the king in the Royal Library they had remained there, forgotten, until rediscovered by Dalton. But even then they attracted ' but little attention, notwithstanding the praise bestowed upon them by William Hunter, to whom they were shown by Dalton, and it was not until 1883 that their existence became generally known by the publication in that year of J. P. Richter's The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci, in which some quotations of the notes accompanying the sketches were given. A little later, when the interest in the literary and artistic remains of Leonardo, now so manifest, had developed, a facsimile reproduction of sixty of the sheets in the Windsor collection was published by Sabachnikoff and Piumati in two beautiful volumes, which contained also a transcription of the manuscript notes and a French translation of them. These volumes appeared in 1898 and 1901 and the second contained a promise that other volumes containing reproductions of the remaining sheets would follow. This promise has, however, remained unfulfilled, possibly because there also appeared in 1901 facsimiles of nearly all the sheets in the collection in ten volumes, edited by Rouveyre. This edition lacked, however, a transcription and translation of the notes and thereby was far from satisfactory, since the crabbed chirography of the fifteenth century, the uncertainty of Leonardo's orthography and, above all, his habit of writing from right to left, makes the translation of the notes from the facsimiles a most arduous task for the ordinary reader. Under these circumstances the necessity for an edition thai would contain all the Windsor folios without exception and a1 the same time give an accurate transcription and translation of the notes appealed to Dr. H. Hopstock, Prosector in Anatomy in the University of Christiania, and having obtained permission to photograph and publish the manuscript through the kind offices of Her Majesty Queen Maud of Norway and having secured as collaborators Dr. A. Fonahn, Professor of the History of Medicine, and Ove C. L. Vangenstcn, Professor of Italian, both of the University of Christiania, the work was begun in 1910 and the first two volumes are now before us. The first volume contains the reproductions of thirteen of the original folios and the second those of twenty-four, each facsimile being accompanied by an accurate transcription of the manuscript notes together with their translation into English and German. Nothing but praise can be given the editors for the care and accuracy with which they have accomplished their task and they are to be congratulated on the manner in which the publisher also has fulfilled his part of it, the beautifully clear reproductions, the excellent letterpress and the entire appearance of the volumes being fully worthy of the important subject matter. The sketches and notes of the first volume are somewhat varied as to subjects, but for the most part bear upon the mechanism of respiration, including the action of the diaphragm, and, to a certain extent, upon the heart, while those of the second volume are very largely concerned with the structure of the heart. Some additional sketches of the heart are promised in a later volume and those on the reproductive organs will appear in the third volume, which may be expected during the present year. A detailed account of Leonardo's Anatomy, as revealed by the volumes before us, would be out of place here; it must suffice to say that his physiology was essentially Galenic and so too his Anatomy, the latter, however, not the Galenic anatomy of the Middle Ages, but a return to the truer anatomy of the classical Galen. But while one cannot concede to Leonardo any important advance in anatomical knowledge beyond that possessed by Galen, in estimating his position in the history of anatomy it is not with Galen that he is to be compared, but with his own more immediate predecessors and contemporaries. His manuscripts are to be assigned to the beginning of the sixteenth century, one of the folios reproduced in the second volume before us bearing the date 1513, and when his figures are compared with those of Ketham (1491), Peyligk (1499), Hundt (1501), Reisch (1504), Phryesen (1518) or Berengarius (1521), they reveal, apart from their artistic superiority, a preeminence in accuracy and careful observation that fully confirm William Hunter's estimate of him as "by far the very best anatomist and physiologist of his time." Leonardo's projected treatise on anatomy was never written, so far as is known, and it is difficult, therefore, to estimate his influence on the revival of anatomy. One can hardly avoid a suggestion that Vesalius may have known of his work and have been influenced by it, although 142 BOOK REVIEW no evidence in favor of such a suggestion has as yet been advanced. And, after all, both Leonardo and Vesalius were products of the Renaissance, when men began to throw off the shackles of tradition and to observe and think for themselves. Nowhere more clearly than in Leonardo's notes can one perceive the spirit of the age. They record observations made and to be made, propound questions as to the significance of parts, and explanations of their action and discuss other probabilities, frequently meeting possible objections from hypothetical opponents. They are full of the spirit of modern science, which, after all, was the spirit of the Renaissance, and in them one can find abundant material for the study of the psychology of that most interesting period in the evolution of modern thought. It is not anatomists alone who owe a debt of gratitude to the editors of these splendid volumes; all students of the Renaissance are equally indebted with them, and all who have had the privilege of studying these first two volumes will join in a sincere wish that it may be possible to complete the reproduction of the remaining Windsor folios at an early date and in the same thorough manner. | |||

J. P. McM. | |||

|} | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

:'''Links:''' [[Historic Embryology Textbooks]] | :'''Links:''' [[Historic Embryology Textbooks]] | ||

| Line 13: | Line 33: | ||

{{Historic Disclaimer}} | {{Historic Disclaimer}} | ||

=Leonardo da Vinci - The Anatomist= | =Leonardo da Vinci - The Anatomist= | ||

[[File:J. Playfair McMurrich.jpg|thumb|150px|alt=J. Playfair McMurrich|J. Playfair McMurrich (1859 – 1939)]] | |||

(1452-1519) | (1452-1519) | ||

Carnegie Institution Of Washington Publication No. 411 (1930) | Carnegie Institution Of Washington Publication No. 411 (1930) | ||

| Line 22: | Line 43: | ||

Professor of Anatomy, University of Toronto | Professor of Anatomy, University of Toronto | ||

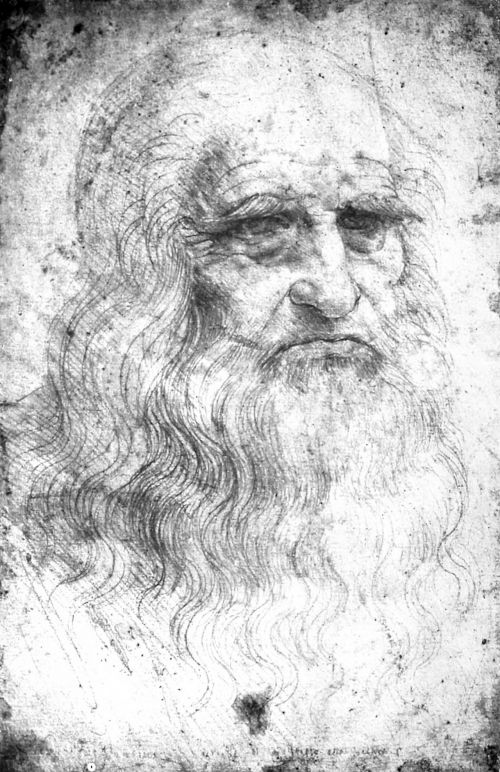

[[File:McMurrich1930 frontispiece.jpg|500px]] | |||

Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, probably by himself. Royal Palace, Turin (Anderson) | Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, probably by himself. Royal Palace, Turin (Anderson) | ||

| Line 49: | Line 72: | ||

[[Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 3|Chapter III Possible Literary Sources of Leonardo’s Anatomical Knowledge]] | [[Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 3|Chapter III Possible Literary Sources of Leonardo’s Anatomical Knowledge]] | ||

[[Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) | [[Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 4|Chapter IV Anatomical Illustration before Leonardo]] | ||

[[Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 5|Chapter V Fortunes and Friends]] | [[Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 5|Chapter V Fortunes and Friends]] | ||

| Line 86: | Line 109: | ||

[[Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 22|Chapter XXII Conclusion]] | [[Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930) 22|Chapter XXII Conclusion]] | ||

==Author’s Preface== | ==Author’s Preface== | ||

Latest revision as of 04:18, 31 March 2020

| Embryology - 25 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

McMurrich JP. Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist. (1930) Carnegie institution of Washington, Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

| Online Editor | ||

|---|---|---|

| This is a draft version of McMurrich's 1930 anatomy history textbook on Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). Note the images online have been adjusted from the original scan versions, in the file history, the first uploaded version is always the original.

|

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Leonardo da Vinci - The Anatomist

(1452-1519)

Carnegie Institution Of Washington Publication No. 411 (1930)

By

J. Playfair McMurrich

Professor of Anatomy, University of Toronto

Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, probably by himself. Royal Palace, Turin (Anderson)

Leonardo da Vinci

THE ANATOMIST

(1452-1519)

By The Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore

Table of Contents

Author’s Preface

Preface by George Sarton

Chapter II Anatomy from Galen to Leonardo

Chapter III Possible Literary Sources of Leonardo’s Anatomical Knowledge

Chapter IV Anatomical Illustration before Leonardo

Chapter V Fortunes and Friends

Chapter VI Leonardo’s Manuscripts, their Reproduction and his Projected Book

Chapter VII Leonardo’s Anatomical Methods

Chapter VIII General Anatomy and Physiology

Chapter IX Leonardo’s Canon of Proportions

Chapter XIII The Blood-vessels

Chapter XIV The Organs of Digestion

Chapter XV The Organs of Respiration

Chapter XVI The Excretory and Reproductive Organs

Chapter XVII The Nervous System

Chapter XVIII The Sense Organs

Chapter XX Comparative Anatomy

Author’s Preface

In attempting to evaluate even one only of the activities of so manyminded a man as Leonardo da Vinci, one is, perforce, led far afield beyond the topics that are of immediate concern, in order that one may endeavor to see these in their proper environment and perspective. The friends who have aided me in these extra-territorial studies have been many, too many to mention individually, but to one, Dr. George Sarton, I am especially indebted. It was at his suggestion that I undertook the study, of which what follows is the result, and throughout its progress his thorough knowledge and clear understanding of the history of mediaeval and Renaissance science have always been at my disposal. He also kindly undertook the preparation of the photographs required for the illustrations, many of these being taken from works in his own library, others from volumes in the Harvard Library and the Boston Medical Library.

To these two libraries I wish to express thanks for the courtesies afforded and I also desire to make grateful acknowledgments to the Library of the University of Toronto, the Toronto Public Reference Library, the Library of the British Museum, and the London Library for the opportunities and privileges granted for the study of the works of Leonardo in their possession. The Leonardo drawings have been reproduced from the facsimile editions enumerated in the bibliography at the end of this volume, except three of them derived from photographs of the firm D. Anderson of Rome. Some pre-Leonardian documents have been borrowed from the publications of Karl Sudhoff and Charles Singer, whose courtesy is appreciated. More specific acknowledgments will be found in the list of illustrations below. Finally I am deeply indebted to Dr. R. K. George for assistance in proof-reading and for the preparation of the index.

J. Playfair McMurrich

University of Toronto

December 16, 1929

Preface

It is always useful to place a work in its historical perspective. The reader’s interest in it is awakened or increased as soon as he knows its genesis and development. This preface is primarily meant to gratify such legitimate curiosity. The fact that I can not speak of the genesis of Dr. McMurrich’s work without speaking of my own studies will not be brought against me, I hope. It can not be helped.

When I was appointed Associate in the History of Science by the Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1918, I undertook to make a thorough study of Leonardo’s thought. 1 However, I soon realized that a proper appreciation of it would be impossible without a deep and accurate knowledge of mediaeval science. To measure Leonardo’s originality it was necessary to be able to distinguish the mediaeval elements which he had assimilated. But was it expedient to include these mediaeval investigations, which are almost endless, in a history of Leonardo’s thought? Was it wise to write a history of mediaeval science around his own personality? After all, however mediaeval Leonardo had remained, the Middle Ages were one thing and Leonardo was another. It was better not to mix the two stories. The example unconsciously given by the great French scholar, Pierre Duhem, was a good warning. His Etudes sur Leonard de Vinci (3 vols., Paris, 19061913) were really misnamed. Duhem devoted considerably more space to mediaeval than to Leonardian thought. This seemed to me a bad method. It would be at once simpler and more rigorous to make as complete an inventory of mediaeval knowledge as possible, studying each layer of it independently and in due succession. Thus w T ould we know how much knowledge each age had added to that of the preceding ones, and when Leonardo’s age would finally be reached, the analysis of his own thought would become relatively easy. I foolishly thought that the making of that inventory — the drawing of that intellectual map of the Middle Ages — would take only a couple of years. That was in 1918-19. I am writing this in August 1929, more than ten years later, and I know that many more years will elapse before the task is completed and Leonardo finally overtaken.

To return to the present work, I realized happily at the very beginning that there was a part of Leonardo’s activity, a major part, for which the investigation of mediaeval sources was relatively simpler and less essential, than was Leonardo’s anatomy. Whatever Leonardo had learned from books, it is clear that the mainspring of his anatomical knowledge was to be found in his own autopsies. In this field as opposed to others (e.g., mechanics, optics, geology) once that the need of direct observation had been really understood — and this was on the whole Leonardo’s outstanding contribution, the source of every one of his discoveries — the observations themselves were relatively easier. Anatomical facts are more tangible than geological and mechanical facts. It is not necessary to isolate them from others; they are already isolated. This does not mean that anatomical observations were easy, far from it, but the program of observation was more obvious in this field than in any other, and the harvest more abundant. Thus with regard to Leonardo’s anatomy, thfe general procedure might reasonably be reversed. Instead of studying the past first, and climbing up to Leonardo, century by century, year by year, it would be legitimate in this case to begin by investigating his drawings and comparing them with the anatomical realities. However, this could be done only by a professional anatomist. Leonardo’s drawings could not be understood nor their genuineness and correctness appreciated except by one thoroughly familiar with the objects represented. A theoretical knowledge of anatomy was in itself insufficient for such a task. The historian must be able to visualize the anatomical details which the artist interpreted — remember, a drawing is always an interpretation — he must be able to recall their very appearance under similar conditions.

1 Carnegie Inst. Wash. Year Book No. 18, 1919, 347-349,

This situation having been explained to the President of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, he approached Dr. McMurrich, who kindly agreed to undertake this important share of the Leonardo project. This was very fortunate, for Dr. McMurrich is not only one of the leading anatomists of America, a man of considerable experience, but he has shown a lifelong interest in the history of anatomy. In him are happily blended the technical and historical qualifications, the scientific and artistic leanings, which are but too often dissociated, and yet which are equally essential for the making of a complete historian of science.

This was more than ten years ago. Many and heavy were the duties — scientific, educational, and administrative — heaped upon Dr. McMurrich’s shoulders, and to Leonardo he could but give his leisure hours. The Carnegie Institution was not impatient. It knew it was losing nothing by waiting a little longer, and that in the fulness of time the task which Dr. McMurrich had promised to undertake would be accomplished.

And here it is! No further introduction of it is needed, and this preface might end here. But the author will forgive me if I take advantage of his book to say a few words of the studies on the history of science which have been promoted by the Carnegie Institution. This is necessary because the activities of the Institution are so many and so diversified, that very few people realize what it has already done in our own field. Its publications on the History of Science, important as they are, are lost among many others, which are probably just as important if not more, but deal with other subjects.

The Institution’s first effort in that direction was to publish the Collected Mathematical Works of George William Hill (4 vols., 1907). Later two ancient catalogues of stars were carefully edited, Ptolemy’s, by C. H. F. Peters and E. B. Knobel (1915); Ulugh Beg’s, by Knobel alone (1917). A fundamental History of the Theory of Numbers was composed by L. E. Dickson (3 vols., 1919-23). Nearer to the present work is George W. Corner’s Anatomical Texts of the Earlier Middle Ages (1927). Finally I may be permitted to mention my own Introduction to the History of Science, of which volume 1, From Homer to Omar Khayyam, appeared in 1927; volume 2, From Rabbi ben Ezra to Roger Bacon, is almost ready to be printed; Volume 3, dealing with the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, will probably be ready in 1933. An assistant, Dr. A. Pogo, is preparing materials for Volume 4, to be devoted to the sixteenth century. It should be noted that while the volumes of my Introduction appear necessarily at distant intervals, they were all begun by me at the same time. That is, materials for these four volumes, and for many subsequent ones, have been systematically collected by me since 1911. A great many of these materials have been published, as they became available, in Isis, since 1913.

These explanations are not given solely for the sake of the Carnegie Institution, though it was worthwhile to bring into light a part of its abundant activity which is generally unknown. There is, I believe, a better reason for giving them. The reader will be helped by them to realize the existence of a new branch of knowledge, of an independent discipline, having its own unity, its own organization, its own methods, and deserving as well as any other to occupy the whole of a scholar’s attention and energy. How strange it is, that in this age of science, it should be considered perfectly natural for a man to dedicate all of his time to, say, American or Canadian history, and that hardly any are allowed to devote themselves with the same continuity to a subject which is far more difficult, because it is at once more complex and less standardized? And yet is not the History of Science the very core of the history of culture? How else can we measure man’s progress, except by the growth of his knowledge? Indeed the history of mankind is essentially the history of a gigantic struggle between light and darkness, between knowledge and ignorance. As the light gradually conquers the surrounding gloom, as science gradually destroys superstition, as rationality gradually replaces irrationality, and order, chaos, so— and not otherwise — does civilization increase. Just think of that and then remember that our universities provide for the study of every kind of history, except the very one which would enable us to understand the progress and the very nature of civilization.

The main trouble with our studies is not so much that they are neglected, but that they are considered fair game for any kind of amateurish efforts. This is of course a natural consequence of the fact that only a very few men are given an opportunity to engage in them as a profession. In so much as so few scientists have yet realized it, one could not repeat too often that the History of Science is itself a legitimate branch of science, that it is just as scientific as we make it, and that for it as for other branches, no good can ever be expected out of idle dilettantism or hasty book making. Whatever advance is made in our knowledge of it, will be due exclusively to honest and patient efforts, such as those made by Dr. McMurrich during the last ten years.

Nowhere does Leonardo’s peculiar genius appear more clearly than in these anatomical investigations. To use the author’s striking comparison “Vesalius was undoubtedly the founder of modern anatomy — Leonardo was his forerunner, a St. John crying in the wilderness.” Leonardo’s originality was due not only to his inherent genius, to the penetration and comprehensiveness of his mind, but also to his ignorance — I almost said, to his innocence. To speak of him as an Hellenist is ridiculous; he was not even a Latinist. We have evidence from his Manuscripts that his knowledge of Latin was very meager. It is probable that he had never made a systematic study of it in his youth; apparently he tried to make up for that deficiency in later years, but we all know that a man’s linguistic limits are largely determined before maturity, especially when his life is a busy one and when he has consecrated himself to a definite and inflexible purpose. Leonardo’s knowledge of Latin was that empirical knowledge which an intelligent Italian would easily obtain, in the quattrocento even more easily than now, because the Italian language was then so much nearer to its Latin origins. It was sufficient for simple needs, but utterly insufficient for abundant reading. Thus Leonardo was mercifully spared the oppressive load of that dialectical and empty learning which had accumulated since the ruins of ancient science and made true originality more and more difficult. To be sure, that learning was not wholly barren, but the little amount of gold which it contained, the timid attempts at experimentation, would filter through to such a man as Leonardo in more than one way. Such experimental knowledge did not need a learned language to be transmitted; nay, it would reach the botteghe of artists and craftsmen more directly than the cabinets of scholars. Thus the best of mediaeval science would be sure to reach Leonardo’s inquisitive mind, while the dross was kept out by the insuperable barrier of his ignorance.

And yet such is the strength and pervasiveness of tradition that in spite of his prophylactic ignorance and aloofness, Leonardo could not entirely escape its prejudices. The barrier was not insuperable after all. There is nothing to prove that he had read Galen. Of course he knew Galen and spoke of him even as most of our contemporaries speak of Einstein or Freud without ever having read them. The physiological knowledge which had been transmitted to him by Mondino, Chauliac, or Benedetti, or better still by the intermediary of his conversations with surgeons or brother craftsmen, that knowledge was purely Galenic. Galenic prejudices were part of the very atmosphere which he was breathing; they were beyond the need of scrutiny or dispute. And so it was that this keen observer saw things not always with his own eyes, but sometimes with those of Galen! The best example of this aberration is Leonardo’s reference to the heart’s septum as sievelike. Not only does it occur repeatedly in his notes, but he even drew a portion of the septum showing pores which do not exist. Galen’s triumphant dogmatism made even a Leonardo see the inexistent. But for this illusion which sidetracked him hopelessly, Leonardo might conceivably have discovered the circulation of the blood before Harvey, for he had as much anatomical and mechanical knowledge as was needed. He had all that was necessary to see the truth, except that in this particular case he was blinded by an overpowering prejudice.

One could not illustrate better the limitations of genius. A man of genius sees further than his fellowmen, further and more clearly, but for all that his range of vision is limited. Leonardo was an extraordinary man, yet he belonged to his environment — fifteenth century Italy — almost as completely as his humbler contemporaries. What else could we expect? This father of modern science was still in many respects a child of the Middle Ages.

This is very well proved in Dr. McMurrich’s memoir. He has admirably brought out not only the outstanding merits of Leonardo’s anatomical studies, their thoroughness and originality, but also their weaknesses, which had to be acknowledged, though they were almost unavoidable. Indeed his purpose was not to write a panegyric but to make a conscientious analysis of Leonardo’s anatomy. He shows clearly how much of it was truly new and prophetic of our modern knowledge, but he also shows and with equal clearness that much of it was less original, or even entirely conventional and wrong. Leonardo was the greatest scientist of his time, but he was imperfect and fallible, even as the greatest scientists of our own time, and for that matter, of all times. One of the main lessons that the History of Science can teach us is this very one — the continual growth of man, and his continual, if slowly decreasing, imperfection.

To conclude I wish to express in the author’s name as well as in my own, our deep gratitude to the Institution, whose enlightened generosity encouraged the preparation of this work and made its publication possible.

George Sarton

Cambridge, Massachusetts,

August 1929

Leonardo da Vinci

THE ANATOMIST (1452-1519)

Ille velut fidis arcana sodalibus olim Credebat libris: ncque, si male gesserat usquam Decurrens alio, ncque si bene — quo fit , ut omnis Votiva pateat veluti descripia tabella,

Vita senis.

Horace. Sat. II, I, 30.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Reference: McMurrich JP. Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist. (1930) Carnegie institution of Washington, Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore.

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 25) Embryology Book - Leonardo da Vinci - the anatomist (1930). Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_Leonardo_da_Vinci_-_the_anatomist_(1930)

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G