Book - Contributions to Embryology Carnegie Institution No.56-2

| Embryology - 20 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Mall FP. and Meyer AW. Studies on abortuses: a survey of pathologic ova in the Carnegie Embryological Collection. (1921) Contrib. Embryol., Carnegie Inst. Wash. Publ. 275, 12: 1-364.

- In this historic 1921 pathology paper, figures and plates of abnormal embryos are not suitable for young students.

1921 Carnegie Collection - Abnormal: Preface | 1 Collection origin | 2 Care and utilization | 3 Classification | 4 Pathologic analysis | 5 Size | 6 Sex incidence | 7 Localized anomalies | 8 Hydatiform uterine | 9 Hydatiform tubal | Chapter 10 Alleged superfetation | 11 Ovarian Pregnancy | 12 Lysis and resorption | 13 Postmortem intrauterine | 14 Hofbauer cells | 15 Villi | 16 Villous nodules | 17 Syphilitic changes | 18 Aspects | Bibliography | Figures | Contribution No.56 | Contributions Series | Embryology History

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Chapter 2. Care and Utilization of the Collection

When a specimen is brought to us in a fresh state, as frequently occurs, we fortunately are free to use our judgment in methods of fixation and preservation. If the embryo is perfectly fresh or possibly living, we use, of course, the most refined fixation, preferably corrosive sublimate with 5 per cent glacial acetic. When the specimen is not perfectly fresh we generally transfer it to a 10 per cent solution of formalin. In all of the circulars sent out, physicians are advised to preserve all abortion material, as soon as possible, in this solution; consequently, when delivered to us, specimens, if not crushed, are generally found to be so well preserved that any part is suitable for refined histological technique. In order to render the physician's task easier, we always send upon request a number of containers filled with a 10 per cent solution of formalin in water. Physicians in active practice frequently allow their abortion material to accumulate, preserving it in these containers, and when half a dozen or more are filled they send them to the laboratory or notify us by telephone, and a messenger is sent for them. Specimens from physicians out of town are, of course, sent by express or parcel post. Although contributors are instructed to ship by express C. O. D., they apparently often find it more convenient to send their material by parcel post, for many specimens come to us in this way.

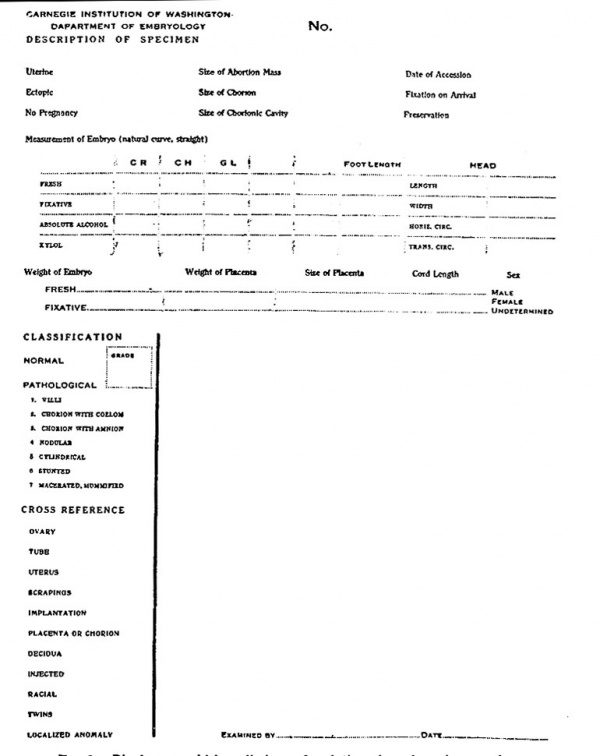

After a specimen reaches the laboratory it is at once given a serial number. It is thus identified in our card catalogue, everything relating to it bearing the same number. The specimen is transferred to another bottle or jar containing the same kind of fluid in which it arrived generally 10 per cent formalin. This jar is not only numbered on the outside, but the serial number of the specimen is placed within, and if the embryo is large enough, a metal tag, bearing its number, is attached to one of the extremities. This makes it possible to store several of the larger specimens in one jar. Likewise, all correspondence concerning the specimen receives this serial number and all data from the wrappers are transcribed upon our permanent records. Photographs are made of all suitable specimens and an objective description recorded on the form shown in figure 2, giving first the dimensions of the entire mass, then the measurements and a description of the villi and chorion, after which the ovum is opened and a note made of its contents. The embryo also is measured, the standard measurement for very young specimens being the greatest distance in the natural posture from crown to rump. This is known in our records as the CR measurement. Older embryos are measured straight and other measurements and weights also are taken. The age of the embryo is estimated on the basis of weight, crown-rump, and foot length, and the estimate so obtained is compared with the menstrual age. One or more photographs are then made and the whole memorandum, together with the clinical history as supplied by the physician and any other data whatsoever, is placed in the permanent files. Special examinations which may be required or suggested are made subsequently and a summary of our records sent to the donor.

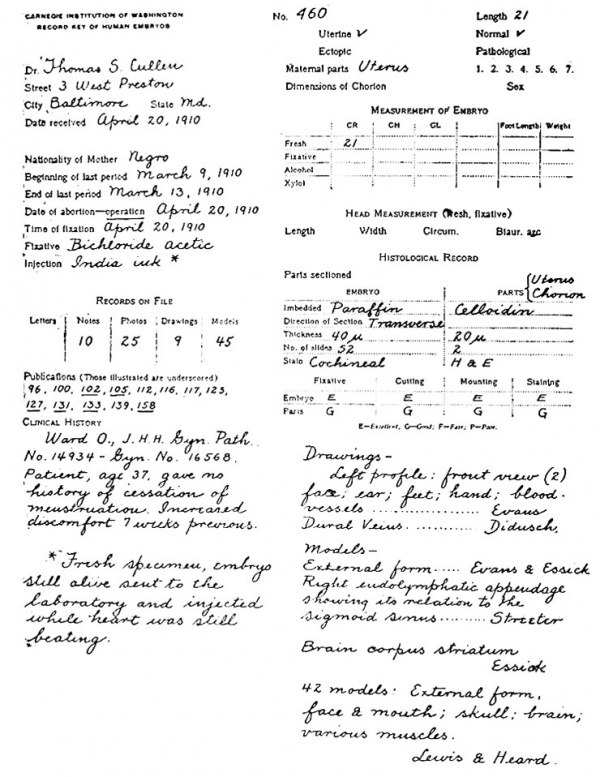

When the collection was taken over by the Carnegie Institution of Washington it was found necessary to open a book in which are recorded all data relating to specimens, a page being devoted to each. As these volumes have proved to be of great value in keeping track of the collection, we have designated them as the Key. A specimen page of the Key, which records embryo No. 460, is reproduced in figure 1. The data collected are entered in the first column. Only the number of letters received and the number of photographs made are recorded here, this being sufficient to show any interested person what may be found in the permanent file. In the latter, each note is stamped with the catalogue number of the specimen and the date of filing, so that notes entered in successive years can easily be arranged in sequence. In the upper part of the second column of figure 1 are recorded the dimensions and general character of the specimen, which, of course, necessitates a general classification, for at this time it must be determined whether or not the embryo is normal or pathological. Since the diagnosis is made entirely upon its general appearance and form, it does not follow, when an embryo is classified as normal, that it necessarily is so, but only that it is normal in form. This point will be discussed later.

Fig. 1. Specimen page from "Key," showing manner in which records of embryos are entered.

Fig. 2. Blank upon which preliminary description of specimen is entered.

In order to facilitate the tabulation of the Key, we have found it necessary to make all descriptions of a specimen on another form (fig. 2), which is so constructed that any data entered are easily transferred to the Key. This information is arranged from the card catalogue, a plan we have found essential in order that any given type of specimen may be located easily. By this time the specimen is fully recognized as normal or pathological, and it has also been determined whether new records or drawings should be made for future reference. The photographs, negatives, letters, notes, and drawings are then filed in numerical order in suitable metal cabinets in a fire-proof vault.

An effort is made to cut into serial sections, as soon as possible, all small embryos that are well preserved. Miscellaneous specimens are likewise constantly being sectioned for instance, an ovary, villi, portions of a chorion, or parts of larger embryos. In order that this may be done without confusion to the investigator, we have found it helpful to record each block under consideration upon a form somewhat similar in character to figures 1 and 2; this we call the histological record, which may be compared to a bill of lading. This sheet is dated and the part of the specimen to be cut is indicated thereon, as are also the directions for embedding, cutting, staining, etc. After the work has been done, the technician returns the slides, with the histological record, to the investigator interested in this particular specimen, who checks up the sections and enters the grade upon the histological record, which is then placed in the permanent file.

Preparations of many specimens for the microtome are constantly under way. Since most of the specimens are delicate and can not be touched, we have had very satisfactory results from passing them through the graded alcohols in shell vials, closely stoppered with absorbent cotton. Within each vial is a loose tag bearing the number of the specimen. Experience has taught us that if there is very careful gradation only five grades of alcohol are necessary, beginning with 60 per cent, then 70 per cent, and so on. With the firm cotton stopper the entrance of the alcohol is so gradual as to equal an infinite number of gradations. For instance, if the specimen is changed from a 60 per cent to a 70 per cent solution, the stopper should be so tight that the diffusion can not become complete for several hours. When passing from lower to higher grades it is preferable to invert the vial. If this were not done, the stronger solution would not enter so quickly, as a 60 per cent fluid has a higher specific gravity than a 70 per cent, and hence there would be a slower mixture. In passing from stronger alcohol to water, on the other hand, the vial should be right end up. The underlying idea of this procedure is based upon the fact that if the ovum is thrown into strong alcohol, the chorion and outer layers of the embryo become greatly shrunken, while the deeper tissues are well preserved, as the alcohol diffuses slowly towards the center of the embryo. After dehydration the specimen is embedded in either celloidin or paraffin, stained, and cut according to the directions given on the histological record, and is then ready for permanent filing.

We have found it convenient to segregate the specimens into two groups. The first includes all embryos which have been cut into serial sections. These are filed according to length, so that any one wishing to study structures in the 4-mm. stage, for instance, will find all such embryos together in the cabinet. There is, however, a very large amount of miscellaneous material which we have been compelled to file merely in numerical sequence, and this constitutes the second group. In order to expedite the work of locating a specimen, each is entered upon the card catalogue according to its length in millimeters, the groupings being a millimeter apart. All normal embryos of the same length are entered upon the same card, with notations as to whether or not they have been cut into serial sections. The pathological specimens are arranged upon cards according to type, but the specimens of a given type or group are also arranged in order of size. In this way it is quite easy to locate a specimen of a given size in any group after it has been sectioned. It can be seen at a glance, therefore, that we have here a list corresponding to all the embryos in the collection, both those which have been cut and those which have not. There are similar cards of all drawings, models, and photographs, and these, in a general way, are arranged according to their anatomical topography. For instance, on one card will be found left profiles, on another right profiles, on another hands, etc.

It is by no means a simple matter to catalogue the miscellaneous material. We have found it necessary to carry a card for ovaries, another for tubes, and so forth, as shown in the second column of figure 2. In the course of time we shall add cards for partial series and for the different tissues and organs of the larger fetuses.

As will be seen from the appended bibliography, our earliest studies in embryology were made from the viewpoint of gross anatomy. The first paper deals with the entire anatomy of an embryo 7 mm. long, and therein are recorded several important discoveries. (As stated before, the model made for this study was by far the most elaborate piece of modeling that had as yet been undertaken.) Following this were papers written for the Reference Handbook, which are more general in character. Finally, the names of collaborators began to appear in the list, the first paper being by J. B. McCallum, on the histogenesis of striated muscle. As the interest of new investigators was enlisted, the scope of the work gradually broadened to include almost the entire field of anatomy, and the 159 papers[1], which are dependent largely upon our collection, may be classified as follows: 18 were written for the purpose of propaganda, as efforts have been made from time to time to gain the interest of physicians who might be in a position to send specimens. It must be admitted, however, that these individual appeals brought few results. After such an appeal we would, perhaps, receive two or three specimens. Then there would be a period of quiescence, and we would have to content ourselves with studying again with greater care the detailed anatomy of small portions of an embryo, since material for more extensive surveys was lacking. But as the collection gradually enlarged, papers on embryometrics were published. These number 14 in all, and include such questions as the age of embryos and curve of growth. As might be expected, most of the studies have been on anatomy, although a single specimen calls for a great deal of time in order to work out the form and relation of the organs. The papers on embryo-anatomy fall naturally into subdivisions which have been recognized by anatomists for centuries. There are 9 papers on topographical embryology, 10 on osteology, 9 on myology, 25 on angiology, 16 on splanchnology, 15 on the genito-urinary system, and 7 on the coelom. The study of brain morphology is, to a certain extent, a science in itself, and there are 24 papers on neurology. Only 9 publications on histogenesis have appeared, but the histogenetic standpoint is considered in many of the other papers enumerated above.

As the collection grew we found an increasing number of specimens which, though peculiar in form, were at first believed to be normal, but which upon closer study proved to be pathological. Thus we were unwittingly carried into the field of abnormal development. In fact, the great problem which confronts us always, in the study of a new specimen, is to determine whether or not it is normal. The experience of embryologists elsewhere has apparently been identical with our own, for frequently one observes in the literature an account of a human embryo, believed at first to be normal, which, upon further consideration, proved to be pathological. Hochstetter has stated that we have no right to consider an embryo normal unless it has been removed by a surgeon at hysterectomy, but our studies along this line have shown that a quite appreciable number of hysterectomies disclose pathological embryos. The criterion of His, who used the comparative method of von Baer in determining the normality of human embryos, is probably more reliable than that of Hochstetter. I believe, therefore, that the best check in the study of the human is a knowledge of comparative embryology.

There are 14 papers in the list that deal with pathological embryology. The first (No. 21) included all specimens up to No. 162, which were believed to be pathological. As we have found the two fields closely related, in these studies we have naturally drifted from pathology into teratology, there being 10 papers on this subject.

Of the 500 papers emanating from the Department of Anatomy of the Johns Hopkins Medical School, there are (in addition to the above-mentioned 159 dealing with human embryology) 115 on experimental embryology. A study of human embryology can not be of great scientific significance unless it be extended through comparative studies and an effort be made to determine, if possible, the causal relations between the developing parts. From the beginning, therefore, experimental studies have been made upon a great variety of subjects, the most important being on organ-forming substances and the influence of the eye-vesicle upon the development of the lens from the ectoderm. We may also at this point call attention to the brilliant studies of Harrison upon the development of the nerves, which demonstrate conclusively the. validity of the neuron doctrine. In making these experiments he developed an ingenious method by which the living isolated cells could be seen under the microscope and their growth followed during a number of days. Later, this work was extended to the study of growth of all kinds of isolated tissues in the warm chamber, now well known as tissue culture.

In nearly all studies on embryo-anatomy it is necessary to resort to methods which will enable one to see the structure and form of organs in their serial sections. As far as possible this is always done by observing the whole embryo or parts of one dissected under the dissecting microscope. A valuable specimen, however, can not be treated in this way. Such a specimen is cut into sections and from the sections an effort is made to reconstruct the anatomy. In the first publication the anatomy of the embryo was worked out by Bern's (1883) method of reconstruction, but unfortunately at that time this method gave little more than the external form, the finer structures being lost in the model. The plan of dissecting the model was then tried, and it soon became clear that success in reconstruction depended very largely upon one's power to visualize the structures from the serial sections, and to some extent upon inventive ability in eliminating a part of the model, as deeper structures can not be shown without removing the superficial ones. Gradually we evolved what we term dissectible wax models, which, however, are somewhat clumsy and usually warp in warm water. Finally, Dr. Bardeen (1901), who is skilled in work of this kind, discovered that excellent results could be obtained by making a foundation model in wax and then projecting and elaborating it as a drawing by the graphic method of His (1892), thus combining the good features of two very valuable methods.

At first our record of sections was made by drawing them with the camera lucida or, better still, in a dark room by the aid of a magic lantern. This, however, is a very laborious and time-consuming task, and has a tendency to check the mental activity of the investigator, for unfortunately the work can not be done successfully by a technical assistant. When the collection was transferred to the Carnegie Institution we availed ourselves of the opportunity to install an accurate projection apparatus patterned somewhat after the one used by His (1892). With this apparatus sections of embryo No. 460, previously referred to, were photographed on glass negatives with an enlargement of 50 diameters. Thus it was possible to make several prints. As the photographs were taken with a 50-mm. planar lens, they show all the details wonderfully well.

As everything which we wished to reconstruct had to be transferred to wax, it was highly desirable that the final model should be composed of some temperatureresisting substance. A method has therefore been devised whereby all the structures desired are eliminated from the wax. Thus, in a block of wax the model is represented in outline by a hole or a series of holes, according to the number of structures to be reproduced, and these holes are subsequently filled with plaster of pans. When this hardens and the wax is removed, the finished plaster model is liberated.

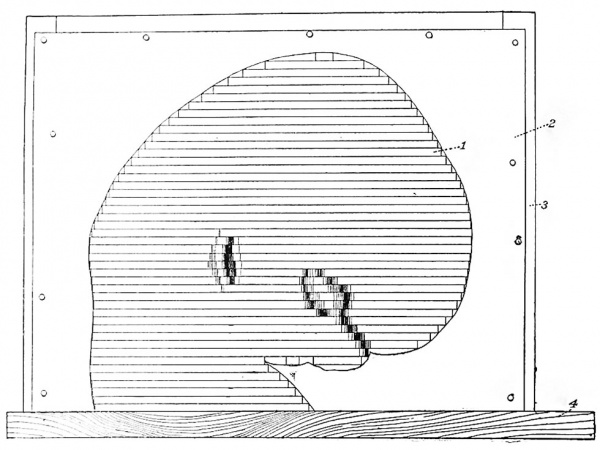

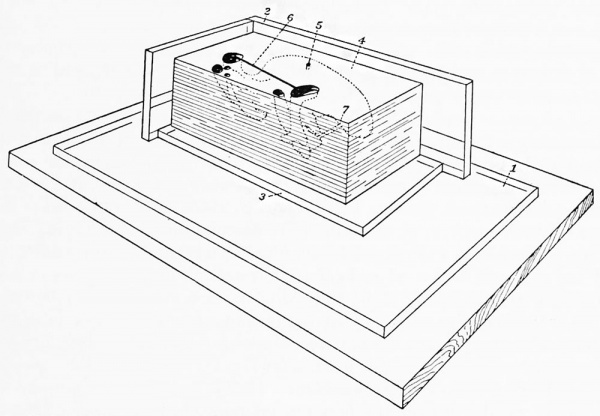

This process of modeling depends solely upon absolute accuracy in superposing the wax plates to correspond to the original sections of the embryo. Hence a perpendicular line must be established, and this is done as follows: The wax plates of the sections are placed one upon another until a complete model of the embryo is built up (fig. 3), the construction being guided by photographs of the embryo made before it was cut. Thus it is possible to duplicate accurately the external form of an embryo on an enlarged scale. After this is done it is a simple matter to mark the wax plates in a perpendicular direction that is, by rightangle lines drawn upon every plate through its axis. These constitute what we call guide-lines, the instrument for marking which was invented by Dr. W. H.

Fig. 3. Method of piling with cardboard outline as guide: 1, external form piled in wax plates; S, cardboard outline guide; 3, posts for attaching same; 4, baseboard.

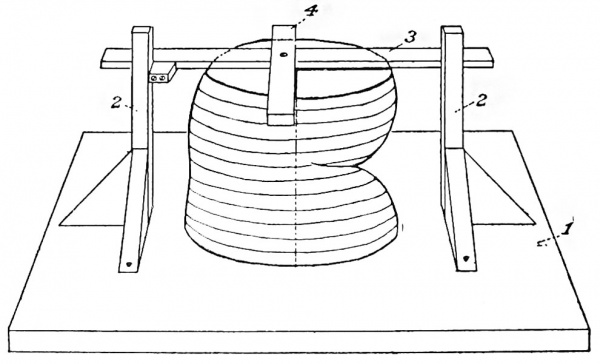

Lewis (1915) and is known as the Lewis guide liner (fig. 4). After the guide-lines have been drawn on each wax plate they are transferred to the photographs or drawings. This is done by superposing each wax plate upon its photograph or drawing and marking the end of the guide-lines. When the wax plate is removed, these points are connected by lines similar to those on the plates. After the two principal guide-lines have been established, it has been found convenient to use secondary guide-lines, 5 cm. apart, which run parallel to the primary ones over the entire surface of the photograph.

Fig. 4. Method of making guide lines: 1, baseboard; 2, perpendicular posts; 3, straight edge; 4, piece at right angles to it.

In order to make a reconstruction of any portion of an embryo it is necessary first to transfer the outlines of that structure from the photograph to the wax plates by means of carbon paper and a glass point used as a pencil. These outlines are then cut and removed from the wax and the plates squared off along the secondary guide-lines sufficiently far outside of the proposed model not to conflict with its casting.

In order that these finished plates, which we call mold plates, may be kept in exact apposition, they are piled in a rectangular corner made of plate glass (fig. 5). While this is being done it is necessary to cut certain artificial channels as vents, so that the air will escape from the openings when the plaster is poured in.

Fig. 5. Method of piling wax mold: 1, baseboard; 2, perpendicular right angle corner; 3, glass plate; 4, wax mold; 6, vent; 6, galvanized iron wire bridge; 7, gate for plaster between parts of mold.

It is also well to bridge loosely attached parts with copper wire, which is done by heating the wire and laying upon the wax plates as they are being piled up. The entire mass forms a mold which, to distinguish it from the others, is called a plate mold. This is cast with plaster of paris, and after the plaster has set the wax is removed by heating. Sometimes it is necessary to proceed farther and make a break mold over the first cast, after which it is possible to make as many duplicate casts as desired. In the above description the main outlines of this valuable method of reconstruction, as now practised in this laboratory, have been given.

Numerous general studies have also been made in embryometrics, in which linear, gravity, and time values are considered. Furthermore, the technique of gross anatomy has been applied to differentiate, by means of injection, the arteries, veins, and lymphatics of the whole clarified embryo. Similar specimens can be prepared to show the entire cartilaginous and bony systems. Thus many embryos frequently are considered in a single publication, especially those illustrating causes of abortion and the production of moles and monsters. Attention is therefore called to the numbers following the references in the appended list of publications. These represent the catalogue numbers of the specimens studied.

It will be noted that certain specimens are referred to frequently, showing that these have been of more general use than others. While these numbers may seem somewhat confusing as they here appear, references to a given embryo are found together in the Key, and this makes it quite easy to find the published description of that embryo. Where the description is accompanied by illustrations, the specimen number is printed in bold type. A comprehensive view of the entire bibliography shows that the papers are sometimes general but often special in character. Whenever the line of thought is general, it is necessary to consider the topic in many different embryos, and one topic is frequently represented by several collaborators. In other words, our department is a large cooperative effort on the part of many contributors and collaborators.

Our first papers were published in the Journal of Morphology and the Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin and Reports, as well as in the foreign journals. We had hoped at that time that the excellent Journal of Morphology would continue, and that it would publish all of our best papers; but unfortunately it could not be financed, and thus for a time we had no adequate outlet for our work. At the Christmas (1900) meeting of the American Association of Anatomists, held in Baltimore, a committee was named to consider the advisability of founding a new journal for the publication of serious anatomical studies. In May following, three trustees (Huntington, Mall, and Minot) were appointed to launch this enterprise. In November of that year the first number of the American Journal of Anatomy appeared, and at the next meeting of the Anatomists, held in Chicago, it was voted to substitute the new journal for the Proceedings of the Association, without additional expense to the members. In this way national support was at once assured. A glance over the first ten volumes of the Journal discloses the fact that about 30 per cent of the papers emanated from the Anatomical Laboratory of the Johns Hopkins Medical School. In other words, our collection was one of the chief incentives for its publication. In rapid succession other journals were established and published in Baltimore; first, the Journal of Experimental Zoology in 1904, then the Anatomical Record in 1906. The stimulus given by these national efforts brought about the revival of the Journal of Morphology by the Wistar Institute in 1908, the opening volume consisting of a monograph entitled "A study of the causes underlying the origin of human monsters" (Mall). These serial publications mark the conversion of our studies of embryology from a local to a national enterprise.

About this time cooperative effort was regenerated by Professor Keibel of Freiburg, and during one of his visits to Baltimore it was agreed that the leading embryologists compile all known facts regarding human development. This compilation was undertaken by 15 embryologists (1 Canadian, 1 Swiss, 2 German, 3 Austrian, and 8 American) and resulted in the production of a two-volume work published in both German and English. One-half of this was produced by the American contributors, and 6 of these 8 used our collection of embryos almost exclusively. The work as a whole certainly does represent progress, and it has also brought our collection into scientific position ; but the editors were not satisfied with their effort, believing it was possible to produce a better work. Before this could be done, however, it was deemed necessary to organize our forces more thoroughly, and to bring this about a plan for the study of human embryology was drawn up by one of the editors[2], which embraced the following features: (1) Much larger collections must be made; (2) much better histories of the various specimens must be obtained; (3) the necessary material must be placed at the disposal of the most competent investigators.

This plan received the full indorsement of leading embryologists, including Keibel and Waldeyer, and was presented to the officers of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, who responded generously with an initial grant of $20,000 to carry on the work for one year as an experiment. At the end of that time a department of embryology of that Institution was established. The Department of Publications of the Carnegie Institution has been of the greatest value to us in our work, for it publishes adequately certain studies which, on account of their expense, could not appear in the journals. These publications, known as the "Contributions to Embryology," are brought out in series at irregular intervals. The first, "On the fate of the human embryo in tubal pregnancy," fills an entire volume. The individual papers appearing therein since then will be found in the appended bibliography.

Publications based upon Studies of the Carnegie Collection

(The numbers following each publication represent the catalogue numbers of the specimens described therein. Where the description is accompanied by illustrations the catalogue number is indicated in bold type.)

- MALL, F. P., 1891. A human embryo twenty-six days old. Jour. Morph., vol. 6, p. 459-480. 2

- 1891. Development of the lesser peritoneal cavity in birds and mammals. Ibid., p. 165 179. 2

- 1893. A human embryo of the second week. Anat. Anz., vol. 8, p. 630-633. 11

- 1893. Early human embryos and the mode of their preservation. Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin, vol. 4. p. 115-121. 2. 6. 11, 12

- 1893. Coelom. Ref. Handb. Med. Sci. Supplement, vol. 9, p. 184-189. 2

- 1893. The heart. Ibid., p. 391-395. 2

- 1893. Development of the thymus. Ibid., p. 875-877. 2

- 1893. Development of the thyroid. Ibid., p. 879-881. 2

- 1893. Human embryos. Ibid., p. 268-269. 2

- 1893. Development of the human coelom. Jour. Morph., vol. 12, p. 395-453. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 28, 29, 32, 34, 37, 42, 43, 45, 48, 53, 55, 57

- 1897. Ueber die Entwickelung des menschlichen Darmes und seiner Lage beim Erwachsenen. Arch. f. Anat. u. Physiol., Anat. Abth., Supplementband. p. 403-432. 2, 6, 9, 10, 12, 34, 45, 48

- MALL, F. P., 1898. Development of the ventral abdominal walls in man. Jour. Morph., vol. 14, p. 347-360. 2, 12, 22, 43, 74, 76

- , 1898. The value of embryological specimens. Maryland Med. Jour. 1, 2, 5. 6, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 34, 35, 42, 45, 46, 49, 52, 57, 72, 76, 79, 80, 81, 87, 88, 92, 94, 95, 96, 98, 99, 105, 106, 109, 116, 117. 118, 121

- , 1898. Development of the internal mammary and deep epigastric arteries in man. Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin, p. 232-235. 2, 43, 76 16.

- , 1898. Development of the human intestine and its position iu the adult. Ibid., p. 197208. 2, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 34, 45, 48

- MACCALLUM, J. B., 1898. On the histogenesis of the striated muscle fiber, and the growth of the sartorius muscle. Ibid., p. 205215. 64, 65, 98

- HENDBICKSON, W. F., 1898. The development of the bile capillaries as revealed by Golgi's method. Ibid., p. 220-221.

- MALL, F. P., 1899. Supplementary note on the development of the human intestine. Anat. Anz., vol. 16, p. 492-495. 34, 45, 79

- BARKER, L. F., 1899. The nervous system. D. Appleton & Co., New York. 2, 6, 9, 12, 18, 19, 43

- CLARK, J. G., 1900. The origin, development and degeneration of the blood vessels of the human ovary. Johns Hopkins Hospital Reports, vol. 9, p. 593-676.

- MALL, F. P., 1900. A contribution to the study of the pathology of early human embryos. Ibid., p. 1-68. 1 2, 5, G, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16. 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30,31, 32,33, 34,35,37,42,45,46,49,52, 54, 55, 57, 58, 60, 69, 70, 71, 72, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 87, 88, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97,98,99, 104,105, 106,109, 110, 115, 116, 117, 118, 121, 122, 123, 124, 127, 128, 129, 130, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 150, 152, 153, 159, 161

- BERRY, J. M., 1900. On the development of the villi of the human intestine. Anat. Anz., vol. 17, p. 242-249. 6, 9, 34, 45, 48

- MACCALLUM, J. B., 1900. On the muscular architecture and growth of the ventricles of the heart. Johns Hopkins Hospital Reports, vol. 9, p. 307-335.

- MALL, F. P., 1901. On the development of the human diaphragm. Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin, p. 158-171. 2, 12, 43, 74, 76, 80, 109, 113, 114, 116, 136, 144, 148, 163, 164

- LEWIS, W. H., 1901. Observations on the pectoralis major muscle in man. Ibid., p. 172-177. 22, 43, 90a, 109, 129, 163

- HARRISON, Ross G., 1901. On the occurrence of tails in man with a description of the case reported by Dr. Watson. Ibid., p. 96-101. 43, 144, 370

- MALL F. P., 1901. Age of human embryos. Ref. Handb. Med. Sci., 2d ed., vol. 3, p. 794-797, 1, 2, 5, 6, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23. 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 34, 42, 45, 46, 49, 52. 57, 72, 76, 79, 80, 81, 87, 88, 92, 94, 96. 99, 105, 106, 109, 116, 117, 118, 121, 138, 144, 145, 146, 148, 149

- BARDEEN, C. R., and W. H. LEWIS, 1901. Development of the limbs, body-wall, and back in man. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 1, p. 135. 2, 12, 22, 43, 76, 106, 109, 144, 148, 163, 167, 175

- MALL, F. P., 1901. Comparative development of the coelom. Ref. Handb. Med. Sci., 2d ed., vol. 3, p. 166-171. 2

- , 1901. Development of the human ccelom. Ibid., p. 171-189. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. 11, 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 28, 34, 42, 43, 45, 48, 57, 58, 123, 130, 134, 137, 143, 147

- LONG, MARGARET, 1901. On the development of the nuclei pontis during the second and third months of embryonic life. Johns Hopkins Hosp. Bull., p. 123-126. 45, 75, 86, 95

- LEWIS, W. H., 1902. The development of the arm in man. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 1, p. 145-183. 2, 12, 22, 43, 76, 80, 109, 163, 164

- MALL, F. P., 1901. Pathological human embryos. Ref. Handb. Med. Sci., 2d ed., vol. 3, p. 797- 809. 11, 13, 14, 21, 24, 25, 29, 32, 37, 54, 55, 58, 60, 69, 70, 72, 77, 78, 79, 81, 82, 87, 93, 94, 97, 104, 110, 115, 122, 123, 124, 128, 130, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 141, 142, 143, 147, 149, 150, 152, 153, 161

- MACCALLUM, J. B., 1902. Notes on the Wolffian body of higher mammals. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 1, p. 245-259. 2, 75. 76, 109, 128, 144, 163, 164

- MALL, F. P., 1902. Development of the heart. Ref. Handb. Med. Sci., 2d. ed.. vol. 4, p. 573-579. 2

- SUDLER, M. T., 1902. The development of the nose and of the pharynx and its derivatives in man. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 1, p 391416. 2, 12, 22, 43, 100, 109, 144, 163, 175

- MALL, F. P., 1903. Second contribution to the study of the pathology of early human embryos. Contr. to Med. Research. Dedicated to Victor C. Vaughan, Ann Arbor, Mich., p. 12-28. 13, 20, 25, 29, 32, 54, 55, 69, 70, 71, 77, 82, 93, 110, 115, 123, 124, 130, 132, 134, 135, 136, 141, 142, 143, 147, 153, 158, 159, 162, 166, 174, 177, 180, 181, 182, 185, 188, 189, 190, 191, 195, 196, 198, 200, 201, 204, 205, 207

- WILLIAMS. J. W., 1903. Obstetrics. 19, 82

- LEWIS, W. H., 1903. Human embryology. New Internal. Encycl. New York. 2, 12, 22, 109, 163

- MALL, F. P., 1903. Notes on the collection of human embryos in the Anatomical Laboratory of the Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins Hosp. Bull. 1 to 35 inc., 37, 42, 43, 45,46,48,49, 52 to 55 inc., 57, 58, 60, 64, 65, 69 to 72 inc.. 74 to 82 inc., 86, 87, 88, 90a, 92 to 99 inc., 104, 105, 106, 109, 110, 113 to 118 inc., 121 to 124 inc., 127-130 inc., 132 to 138 inc., 141 to 150 inc., 152, 153, 158, 159, 161 to 164 inc., 166, 167, 174, 175, 177, 180, 181, 182, 185, 188, 189, 190, 191. 195, 198, 200, 201, 204, 205, 207

- , 1903. On the transitory or artificial fissures of the human cerebrum. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 2, p. 333-339. 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 12, 18, 19, 22, 43, 45, 48, 57, 74, 76, 80, 86, 88, 95, 96. 100, 105, 106, 109, 113, 114, 116, 118, 138, 139, 144, 146, 148, 149, 151, 163, 164, 169, 170, 175. 179, 196, 206. 218

- PEAKCE, R. M., 1903. The development of the islands of Langerhans in the human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 2., p. 445-455. 22, 23, 34, 42, 45, 48

- GAGE, S. P., 1903. Serial order of segments in the fore-brain of three and four weeks human embryos. Science, n. s., vol. 17. p. 486. 148

- , 1904. The mesonephros of a three weeks human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 3, p. VI. 148

- MALL, F. P., 1904. Development of the thymus gland. Ref. Handb. Med. Sci., 2d ed., vol. 6, p. 568570. 2, 12, 109, 163

- , 1904. Development of the thyroid. Ibid., p. 570-574. 2, 109, 163, 175

- LEWIS, W. H., 1904. Development of the foetus. Ibid., p. 450-457. 2, 12, 22, 109, 163

- MEYER, A. W., 1904. On the structure of the human umbilical vesicle. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 3, p. 155-156. 2, 11, 12, 18, 22, 76, 80, 113, 145, 163, 167, 175, 176, 184, 187

- STREETER, G. L., 1904. Peripheral development of the cranial and spinal nerves in the occipital region of the human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 4, p. 84-116. 2, 144, 148

- MALL, F. P., 1904. On the development of the blood-vessels of the brain in the human . embryo. Ibid., p. 1-18. 2, 74, 109, 144, 145. 163, 225, 234, 234b, 235, 237, 238

- POHLMAN, A. G., 1904. Concerning the embryology of kidney anomalies. Amor. Mod., vol. 7, p. 987-990. 175

- , 1905. Abnormalities in the form of the kidney and ureter dependent on the development of the renal bud. Johns Hopkins Hosp. Bull., p. 51-60. 2, 22, 43, 76, 114, 144, 163, 164, 175, 221

- , 1904. Has a persistence of the Mullerian duct any relation to the condition of the cryptorchidism? Amer. Med., vol. 8, p. 1003-1006. 22, 88

54. , 1905. A note on the developmental relations of the kidney and ureter in human embryos. Johns Hopkins Hosp. Bull., p. 4951. 2, 22, 43, 45, 48, 74, 75, 80, 84, 88, 113, 114, 144, 163, 172, 211, 224

55. GAOE, S. P., 1905. The total folds of the fore-brain, their origin and development to the third week in the human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 4, p. IX. 12, 148, 209

56. BARDEEN, C. R., 1905. Studies of the development of the human skeleton. Ibid., p. 265-302. 2, 10, 17, 22, 45, 57, 74, 75, 76, 79, 84, 85, 86, 97, 109, 144, 145, 163, 175, 188, 216, 226, 229

57. , 1904. Numerical vertebral variation in the human adult and embryo. Anat. Anz., vol. 25, p. 497-519. 6, 7, 9, 10, 17, 22, 43, 45, 57, 74, 75, 79, 80, 86, 94, 96, 100, 106, 108, 144, 145, 175, 178, 184, 188, 207, 211, 216, 224, 226, 229

58. , 1905. Development of the thoracic vertebrae in man. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 4, p. 163-174. 2, 17, 22, 23, 44, 45, 76, 79, 80, 84, 96, 106, 108, 109, 144, 145, 163, 175, 184, 186, 216, 221, 241

59. GAOE, S. P., 1905. A three weeks human embryo with especial reference to the brain and the nephric system. Ibid., p. 409-443. 12, 80, 148, 164, 209

60. BRODEL, MAX, 1905. The embryology of the vermiform appendix. In Kelly and Hurdon: Vermiform Appendix and its Diseases. Saunders, Philadelphia, p. 55-58. 9, 10, 28, 52, 89, 202

61. JACKSON, C. M., 1905. On the topography of the pancreas in the human fcetus. Anat. Anz., vol. 27, p. 488-510. 43, 114

62. STREETER, G. L., 1905-06. Concerning the development of the acoustic ganglion in the human embryo. Verhandl. d. Anatom. Gesell. Anat. Anz., vol. 4, and Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 5, p. I. 2, 22, 86, 109, 144, 148, 163

63. MALL, F. P., 1904. Catalogue of the collection of human embryos in the Anatomical Laboratory of the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. (Printed privately.) 1 to 253 inc.

64. HILL, EBEN C., 1906. On the Schultze clearing method as used in the Anatomical Laboratory of the Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins Hosp. Bull., p. 111-115.

65. , 1906. On the embryonic development of a ease of fused kidneys. Ibid., p. 115117. 43, 144

66. STREETER, G. L., 1906. Development of membraneous labyrinth and acoustic ganglion in the human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 5, p. VII.

67. GAOE, S. P., 1906. Total folds of the brain tube in the embryo and their relation to definite structures. Ibid., p. IX.

68. MALL, F. P., 1906. A study of the structural unit of the liver. Ibid., p. 227-308. 2, 6, 9, 10, 12, 22, 76, 80, 109, 117, 148, 163, 186

69. , 1906. On ossification centers in human embryos less than one hundred days old. Ibid., p. 433-458. 22, 42, 53, 59, 156, 167, 168, 202, 214, 240, 2636, 263ft 1 , 2636 2 , 263c, 266, 271, 272, 274, 282, 284, 2886, 300, 306a, 3066, 306c, 326, 329, 333

70. GAGE, S. P., 1906. The notochord of the head in human embryos of the third to the twelfth week, and comparisons with other vertebrates. Science, vol. 24, p. 295.

71. STREETER, G. L., 1907. On the development of the membraneous labyrinth and the acoustic and facial nerves in the human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 6, p. 139-165. 2, 22, 75, 86, 109, 144, 148, 163, 175, 229, 371

72. MALL, F. P., 1907. The collection of human embryos at the Johns Hopkins University. Anat. Rec., vol. 1, p. 14-15.

73. BARDEEN, C. R., 1907. Development and variation of the nerves and the musculature of the inferior extremity and of the neighboring regions of the trunk in man. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 6, p. 259-386. 2, 22, 109, 144, 145, 163

74. STREETER, G. L., 1907. Development of the inter-forebrain commissures in the human embryo. Anat. Rec., vol. 1, p. 55 3

75. MALL, F. P., 1907. A study of the causes underlying the origin of human monsters. (Third contribution to the study of the pathology of human embryos.) Jour. Morph., vol. 19, p. 3368. Also monograph published by the Wistar Institute of Anatomy, Philadelphia, 1908. 1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19. 20, 21,22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, 35,37,42,45,53,54,55,57.58, 60, 69, 70, 71, 72, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 87, 88, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 99, 104, 106, 109, 110, 115, 116. 118, 122, 123, 124, 127, 128, 129, 130, 132. 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 147, 148, 150, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 158, 159, 160, 161, 163, 164, 166, 168, 169, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, ISO, 181, 182, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 192, 194. 195, 196, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 221, 223, 224, 226, 227, 228, 229, 230, 232, 233, 239, 240, 241, 242. 243, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 250, 251, 252, 253, 255, 256, 257, 258, 259, 261, 262, 263d, 264, 268, 269, 270, 274. 275, 276, 278, 279, 280, 282, 285, 286, 288a, 289, 290, 291, 292a, 293, 295, 297, 298, 299, 301, 302, 304,307, 308, 309, 310, 311, 312, 316, 317, 318, 320, 321, 323, 324, 325, 328, 329, 330a, 330b, 334, 336, 338a, 339, 340, 341, 342, 343, 344, 345, 346, 347, 348, 353, 357, 358, 360, 361, 362, 363, 364, 365, 366, 367, 369, 373, 375, 377a, 378, 379, 384, 388, 389, 391, 395, 396, 398, 399, 400, 402, 403

76. BARDEEN. C. R., 1908. Vertebral regional determination in young human embryos. Anat. Rec., vol. 2, p. 99-105. 2, 109

77. STREETEB, G. L., 1908. The nuclei of origin of the cranial nerves in the 10 mm. human embryo. Anat. Rec., vol. 2, p. 111-115. 148

78. BARDEEN, C. R., 1908. Early development of the cervical vertebra and the base of the occipital bone in man. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 8, p. 181-186. 22, 144

79. RETZEK, ROBERT, 1908. Some results of recent investigations on the mammalian heart. Anat. Rec., vol. 2, p. 149-155.

80. EVANS, H. M., 1908. On an instance of two subclavian arteries of the early arm bud in man and its fundamental significance. Ibid., vol. 2, p. 411-424. 148

81. ESSICK, E. R., 1909. On the embryology of the corpus pontobulbare and its relation to the development of the pons. Ibid., vol. 3, p. 254-257. 22, 45, 81, 382

82. SABIN, F, R., 1909. The lymphatic system in human embryos with a consideration of the morphology of the system as a whole. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 9, p. 43-91.

6, 22, 74, 82, 84, 95, 96, 106, 109, 128, 144, 172, 224, 296, 350, 353, 382. 397, 413, 423, 424

83. MALL, F. P., 1910. Die Alterbestimmung von menschlichen Embryonen und Feten. KeibelMall Handbuch der Entwicklungsgeschichte des Menschen, Leipzig, vol. I. Eng. ed. Philadelphia, p. 185-207. 1, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 inc., 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 40 to 54 inc., 56, 57, 59, 61, 62, 64 to 68 inc., 71, 72, 74, 75, 77, 79, 80, 84 to 90d inc., 92, 93, 94, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 105, 106, 108, 109, 113, 114, 116, 117, 118, 120, 121, 125 to 131 inc., 136, 138 to 141 inc., 144, 145, 146, 148, 149, 151, 152, 153, 155, 156, 160, 163, 164, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 175, 176, 178, 183, 184, 186, 187, 188, 192, 193, 194, 199, 200, 202, 203, 206, 208, 210, 211, 213, 214, 216, 217, 219, 221, 224, 227, 229, 231, 239 to 242, 245, 248, 249, 256, 259, 260, 263a, 263b, 263b l , 263b 2 , 263c, 266, 267, 269, 272, 273, 274, 278, 282, 283a, 283b, 283c, 284, 288b, 288c. 296, 300, 301, 305, 306a, 306b, 306c, 306d, 306f, 306g, 306h, 308, 313, 314, 315, 317, 318, 319, 322, 326, 327, 329, 331, 337, 349, 350, 351, 352, 353, 354, 355, 356, 360, 361, 362, 363, 368, 371, 372, 373, 374, 375, 376, 377b, 377c, 377d, 380, 382, 383, 384, 387, 388, 389, 390, 391, 392, 393, 394, 397, 403, 405, 406, 409, 410, 411, 412

84. , 1910. Die Pathologic des mcnschlicha Eies. Ibid., p. 208-248. 12, 21, 32, 77, 78, 79, 80, 115, 122, 124, 128, 133, 135, 162, 201, 243, 250, 256, 2S7, 258, 278, 285, 286, 292a, 293, 297, 304, 310, 323, 328, 340, 343, 360, 364, 367, 379

85. BARDEEN, C. R., 1910. Die Entwickelung des skeletts und des Bindesgewebes. Ibid., p. 296-456. 2, 12, 22, 76, 79, 80, 84, 108, 109, 144, 145, 163, 175, 184, 186, 241

86. LEWIS, W. H., 1910. Die Entwickelung des Muskelsystems. Ibid., p. 457-526. 2, 22, 109, 144, 163

87. MALL, F. P., 1910. Die Entwicklung des Coloms und des Zwerchfells. Ibid., p. 527-552. 2, 12, 43, 74, 76, 80, 109, 113, 116, 136, 144, 148, 163, 164, 239, 391

88. DANDY, W. E., 1910. A human embryo with seven pairs of somites measuring about 2 mm. in length. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 10, p. 85-98. 391

89. MINOT, C. S., 1910. Laboratory Textbook of Embryology. Philadelphia. 391

90. STREETEB, G. L., 1911. Die Histogenese des Nervengewebes. Keibel-Mall Handbuch, Bd. 2, Leipzig and Philadelphia, p. 1-156. 2, 22, 109, 144, 163, 220, 234

91. MALL, F. P., 1910. A list of human embryos which have been cut into serial sections. Anat. Rec., vol. 4, p. 355-367. 1 to 10 inc., 12, 13, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23, 34, 43, 44, 45, 48, 57, 74, 75, 76, 80, 84, 86, 87, 88, 95, 96, 100, 106, 108, 109, 112, 113, 114, 116, 120, 128, 134, 136, 144, 145, 146, 148, 163, 164, 170, 172, 175, 179, 184, 186, 187, 199, 208, 209, 211, 216, 219, 220, 221, 224, 227, 229, 231, 234, 239, 240, 241, 242, 245, 248, 249, 250, 253, 256, 267, 268, 278, 289, 293. 296, 306a, 314, 317, 318, 338a, 349, 350, 351, 352, 353, 368, 371, 372, 380, 382, 383, 384, 387, 388, 389, 390, 391, 397, 404, 405, 406, 409, 422, 423, 424, 431. 432, 447, 449, 452

92. WILSON, L. B., and B. C. WILLIS, 1911. A comparative study of the histology of the so-called hypernephromata and the embryology of the nephridial and adrenal tissues. Jour. Med. Research, vol. 24, p. 73-90. 144, 353, 371, 406

93. LISSER, H., 1911. Studies on the development of the human larynx. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 12, p. 27-66. 22, 43, 109, 128, 144, 317

94. LEWIS, F. T., 1911. Die Entwicklung dea Darmea und der Atmungsorgane. Keibel-Mall Handbuch, vol. 2, Leipzig and Philadelphia, p. 282-482. 391

95. MINOT, C. S., 1911. Die Entwicklung des Blutes Ibid., p. 483-517. 350, 353

96. EVANS, H. M., 1911. Die Entwicklung dcs Blutgefasseystems. Ibid., p. 551-688. 2, 6, 43, 57, 80, 108, 109, 144, 145, 148, 163, 229, 349, 353, 368, 382, 390, 391, 448, 449, 453, 460

97. SABIN, F. R., 1911. Die Entwicklung dea Lymphgefass-systems. Ibid., p. 688-724.6, 22, 57, 74, 86, 96, 106, 109, 128, 144, 163, 172, 224, 296, 317, 350, 353, 382, 397, 409, 423, 424, 448

98. POHLMAN, A. G., 1911. The development of the cloaca in human embryos. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 12, p. 1-23. 2, 12, 22, 43, 76, 80, 87, 109, 113, 114, 116, 128, 148, 164, 175, 186, 209, 221, 240, 241, 256, 296, 317, 350, 353, 371, 383, 391, 397, 409

99. WHITEHEAD, R. H., and J. A. WADDELL, 1911. The early development of the mammalian sternum. Ibid., p. 89-106. 109, 144, 175, 296, 423, 424

100. MALL, F. P., 1911. Report upon the collection of human embryos at the Johns Hopkins University. Anat. Rec., vol. 5, p. 343-357. 1 to 500 inc. (No illustrations.)

101. ESSICK, C. R., 1912. The development of the nuclei pontis and the nucleus arcuatus in man. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 13, p. 25-54. 22, 75, 84, 86, 95, 96, 128, 145, 172, 184, 199, 211, 219, 227, 368, 382, 405, 484, 490, 491, 508, 509

102. MALL, F. P., 1912. On the development of the human heart. Ibid., p. 249-298. 2, 3, 33, 43, 46, 80, 86, 90a, 90b, 90c, 90d. 109, 113, 116, 136, 144, 163, 175, 239 241, 249, 283b, 296, 317, 318, 353, 356, 360, 368, 380, 384, 386, 390, 397, 406, 409, 422, 423, 424, 426, 431, 432, 434, 460, 463, 470

103. LCWSLEY, O. S., 1912. The development of the human prostate gland with reference to the development of other structures at the neck of the urinary bladder. Ibid., p. 299-346. 34, 54

104. MALL, F. P., 1912. Bifid apex of the human heart. Anat. Rec., vol. 6, p. 167-172. 90b, 118, 283b, 353, 360, 434, 455

105. SABIN, F. R., 1912. On the origin of the abdominal lynphatics in mammals from the vena cava and the renal veins. Ibid., p. 335342. 460

106. MALL, F. P., 1912. Aneurysm of the membranous septum projecting into the right atrium. Ibid., p. 291-298. 113, 164, 353, 391, 463

107. HUBER, G. CARL, 1912. On the relation of the chorda dorsalis to the anlage of the pharyngeal bursa or median pharyngeal recess. Ibid., p. 373404. 221, 371, 389, 406

108. MELLUS, E. L., 1912. The development of the cerebral cortex. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 14, p. 107-117. 491

109. WILLIAMS, J. W., 1912. Obstetrics. 3d ed., N. Y. 19, 82, 164, 278, 550

110. LOWSLEY, O. S., 1913. The human prostate gland at birth with a brief reference to its fetal development. Jour. Amer. Med. Assn., vol. 60, p. 110. 34

111. MALL, F. P., 1913. A plea for an institute of human embryology. Ibid., p. 1599-1601.

112. SABIN, F. R., 1916. The origin and development of the lymphatic system. Johns Hopkins Hosp. Reports, n. s., vol. 17, p. 347-440. 86, 163, 353, 397, 460

113. MALL, F. P., and E. K. CULLEN, 1913. An ovarian pregnancy located in the Graafian follicle. Surg., Gyn. and Obst., vol. 17, p. 698-703. 550

114. MALL, F. P., 1913. Report on Embryological Research. Carnegie Inst. Wash. Year Book No. 12.

115. EVANS, H. M., 1914. An appeal to surgeons for embryological material. (Printed privately.) 391, 626, 763

116. SABIN, F. R., 1913. Der Ursprung und die Entwickelung des Lymphgefass-systems. (Ergebnisse der Anatomic und Entwickelungs-geschichte.) Anat. Hefte, Abth. II, p 1-97. 86, 163, 353, 460

117. MALL, F. P., 1914. On stages in the development of human embryos from 2-25 mm. long. Anat. Anz., vol. 46, p. 78-84. 2, 5, 9, 19, 22, 43, 74, 80, 106, 109, 127. 128, 144, 156, 163, 167, 175, 208, 221, 229, 240, 241, 245, 248, 256, 296, 317, 349, 353, 350, 368, 371, 372, 387, 388, 389, 390, 397, 405, 406, 409, 422, 423, 424, 431, 447, 453, 460, 463, 485, 492, 500, 511, 536, 544, 547, 552, 558, 562, 566, 576, 584a, 590, 617, 623, 626, 630, 632

118. BARDEEN, C. R., 1914. The critical period in the development of the intestine. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 16, p. 427-436. 2, 6, 9, 10, 34, 43, 45, 79

119. BREMEH, L., 1914. The earliest blood-vessels in man. Ibid. p. 447. 391

120. BIOELOW, P., 1914. Coelom. Ref. Handbook Med. Sci., 3d ed., vol. 3, p. 138-148. 2, 6, 9, 12, 18, 19, 22, 34, 43, 45, 391

121. EVANS, H. M., 1914. An appeal to physicians for embryolopiral material. (Printed privatelv.) 391, 626, 763

122. BEITLEH, F. V., 1914. Still-born children. State Dept. Health of Maryland, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

123. MALL, F. P., 1914. Annual report of the Director of the Department of Embryology. Carnegie Inst. Wash. Year Book No. 13, p. 107-115. 1 to 811 inc.

124. , 1915. Department of Embryology. Reprinted from "Scope and Organization" of the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

125. MEYER, A. W., 1914. Curves of prenatal growth and autocatalysis. Arch. f. Entwicklungsmech. d. Organ., Bd. 40, p. 497-525.

126. MALL, F. P., 1915. On the fate of the human embryo in tuhal pregnancy. Contributions to Embryology, No. 13, Carnegie Inst. Wash. Pub. No. 221, p. 5-103. 109, 154, 175, 179, 183, 196, 197, 256, 294, 298, 307, 314, 324, 338c, 342, 350, 352, 361, 367, 369, 378, 387, 389, 390, 396, 402, 415, 418, 422, 426, 430, 431, 432, 448, 449, 456, 458, 472, 473, 477, 478, 479, 481, 484, 487, 488, 495, 496, 497, 503, 507, 513, 514, 515, 517, 519, 520, 524, 535, 539, 540, 553, 554, 561, 567, 570, 575, 576, 597, 602, 612, 634, 640, 657, 659, 667, 670, 678, 676, 685, 686, 694, 697, 706, 720, 726, 728, 729, 734, 741, 742, 754, 762, 763, 765a, 766, 772, 773c, 775, 777, 782, 784, 787, 790, 794, 804, 808, 809, 809b, 809c, 815, 825, 835, 836, 838, 846, 851, 867, 874, 881, 882, 889, 891, 892, 898, 899, 900b, 900c, 900d, 900e, 900f, 900g, 900j, 904, 908, 910, 911, 919, 927, 928, 932, 934, 938, 939, 945, 953, 967a, 967b, 967c, 974, 977, 990, 992, 995. 998

127. CLARK, E. R., 1915. An anomaly of the thoracic duct with a bearing on the embryology of the lymphatic system. Contributions to Embryology, No. 3, Carnegie Inst. Wash. Pub. No. 222, p. 45-54. 460

128. ESSICK, C. R., 1915. Transitory cavities in the corpus striatum of the human embryo. Contributions to Embryology, No. 6., Carnegie Inst. Wash. Pub. No. 222, p. 95-108. 144, 350, 409, 431

129. WALLIX, IVAN E., 1913. A human embryo of thirteen somites. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 15, p. 319-331. 1201a

130. METER, A. W., 1915. Fields, graphs, and other data on fetal growth. Contributions to Embryology, No. 4, Carnegie Inst. Wash. Pub. No. 222, p 5568. (Many of our embryos considered.)

131. STBEETER, G. L., 1915. The development of the venous sinuses of the dura mater in the human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 18, p. 145, 178. 84, 95, 96, 128, 144, 145, 199, 224, 234a, 296, 349, 350. 382, 448. 449, 458. 460, 544, 588, 613, 632, 886, 940, 966

132 LEWIS W H 1914. Development of the fetus. Ref. ' Handbook Med. Sci.. 3d ed., p. 373-384. 2, 12, 22, 91, 109, 163

133 1915. The use of guide planes and plaster of paris for reconstruction from serial sections: some points on reconstruction. Anat. Rec., vol. 9, p. 719-729. 460

134. MALL, F. P., 1915. The cause of tubal pregnancy and the fate of the inclosed ovum. Sur., Gyn. and Obst., vol. 22, p. 289-298. 154 196, 298, 307, 314, 324, 361, 367, 378, 396 415, 418, 430, 472, 477, 478, 479, 488, 495, 507, 513, 514, 515, 517, 519, 520, 524, 539 540, 553, 554, 561, 567, 570, 575, 602, 659, 673, 685, 686, 694, 720, 726, 729, 734, 741 754, 762, 765a, 766, 772, 773, 775, 777, 784, 787, 794, 804, 808, 809b, 809c, 815, 825, 835, 838, 846, 874, 881, 882, 891, 892

135. KINGSBURY. B. F., 1915. The development of the human pharynx. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 18, p. 329-386. 105, 213, 301

136. MALL, F. P., 1915. Development of the heart. Ref. Handbook Med. Sci., 3d ed., vol. 5. 2

137 LOWSLET, O. S., 1915. The prostate gland in old age. Annals of Surgery, vol. 62, p. 716-737.

138. JENKINS, GEORGE B., 1916. A study of the morphology of the inferior olive. Anat. Rec., vol. 10, p. 317-334. 491, 619, 625

139. STREETER, G. L., 1916. The vascular drainage of the endolymphatic sac and its topographical relation to the transverse sinus in the human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 19, p. 67-89. 96, 448, 449, 458, 460, 632, 1018, 1131

140. MILLER, W. S., 1914. Digestive tract. Ref. Handbook Med. Sci., 3d ed., vol. 3. 6, 9, 10, 45

141. CULLEN, THOMAS S., 1916. Embryology, anatomy and diseases of the umbilicus. W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia and London. 2,86,317,391

142. MALL, F. P., 1917. Annual report of the Director of the Department of Embryology, Carnegie Inst. Wash. Year Book, No. 14, p. 111-125.

143. , 1916. The human magma reticule in normal and in pathologic-al development. Contributions to Embryology, No. 10, Carnegie Inst. Wash. Pub. No. 224, p. 5-26. 12, 21, 78, 79, 94, 104, 122, 135, 136, 148, 164, 211, 230, 244, 250, 261, 270, 278, 318, 391, 402, 463, 470, 486, 512, 531, 533, 543, 545, 560, 576, 584a, 588, 604, 605, 636, 651g, 660, 763, 779, 813, 836, 991, 1117, 1189

144. , 1916. The embryological collection of the Carnegie Institution. Circular No. 18. (Printed privately.)

145. EVANS, H. M., and G. W. BARTELMEZ, 1917. A human embryo of seven to eight somites. Anat. Rec., vol. 12, p. 355. 1201

146. STREETER, G. L., 1917. Histogenesis of the otic capsule. Anat. Rec., vol. 12, p. 417. 22, 84, 86, 95, 172, 353, 588, 1018, 1373, 1400-30

147. WHEELEK, T., 1917. Study of a human spina bifida monster with enccphaloceles and other abnormalities. Anat. Rec., vol. 12, p. 431. 862a

148. MALL, FRANKLIN P., 1917. Organization and Scope of the Department of Embryology, Circular No. 19. (Printed privately.)

149. f 1917. Note on abortions with letters from the Health Commissioner of Baltimore and from the Chief of the Bureau of Vital Statistics of Maryland regarding registration and shipment of embryos to the Carnegie Laboratory of Embryology at the Johns Hopkins Medical School. Baltimore. Circular No. 20. (Printed privately.)

150. , 1917. Annual report of the Director of the Department of Embryology, Carnegie Inst. Wash. Year Book No. 15, p. 103-120. 1 to 1458 considered.

151. SABIN, F. R., 1915-16. The method of growth of the lymphatic system. The Harvey Lectures, Series XI, p. 124-145.

152. STREETER, G. L., 1917. The development of the scala tympani, scala vestibuli and perioticular cistern in the human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 21, p. 299-320. 84, 199, 886, 1018, 1400-30'

153. MALL, FRANKLIN P., 1917. Cyclopia in the human embryo. Contributions to Embryology, No. 15, vol. 6, Carnegie Inst. Wash. Publication 226, p. 5-33. 12, 148, 163, 201, 391, 470, 559, 836, 1165, 1178a, 1178b, 1201.

154. YOUNG, H. H., and E. G. DAVIS, 1917. Double ureter and kidney with calculous pyronephrosis of one half; cure by resection. The embryology and surgery of double ureter and kidney. Jour. Urol., vol. 1, p. 17-32. 371, 453, 800, 87.3, 988, 1075, 1197, 1354

155. GAGE, S. H., 1917. Glycogen in the nervous system of vertebrates. Jour. Compar. Neurol, vol. 27, p. 451-464.

156. MALL, FRANKLIN P., 1917. On the frequency of localized anomalies in human embryos and infants at birth. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 22, p. 49-72. 6, 10, 12, 31, 80, 81, 94, 112, 124, 128, 164, 182, 186, 189, 201, 212, 226, 228, 230, 242a, 242b, 249a, 249b, 250, 276, 293. 295, 302, 306a, 314, 316, 328, 335, 338a, 338c, 344, 364, 365, 370, 371, 413, 433a, 466, 499, 510, 511, 552, 558, 559, 584a, 622, 627, 646, 649, 651a, 651f, 653, 676, 710, 732, 740, 749, 768b, 768c, 779, 785, 789, 796, 797, 802, 808, 813, 839, 842. 862, 862a, 862b, 868, 874b, 982, 996, 1140b, 1289, 1295g, 1315, 1330, 1477, 1523, 1690, 1749 (1000 specimens from 1 to 900g treated statistically.)

157. STREETER, GEOROE L., 1917. The factors involved in the excavation of the cavities in the cartilaginous capsule of the ear in the human embryo. Amer. Jour. Anat., vol. 22, p. 1-25. 86, 95, 96, 296, 409, 453, 455, 575, 695, 719, 721, 886, 1373

158. WEED, LEWIS H., 1917. The development of the cerebro -spinal spaces in pig and in man. Contributions to Embryology, vol. 5, No. 14, Carnegie Inst. Wash. Pub. No. 225, p. 7-16. 75, 144, 199, 390, 405, 406, 409, 431, 448, 453, 460, 544, 576, 617, 632, 695, 721, 745, 782, 836, 849, 870, 900ft, 928e, 1008, 1131, 1134

159. WILLIAMS, J. WHITRIDGE, 1917. Obstetrics. 4th ed. D. Appleton & Co., New York and London. 19, 88, 164, 278, 550, 782

| Embryology - 20 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Mall FP. and Meyer AW. Studies on abortuses: a survey of pathologic ova in the Carnegie Embryological Collection. (1921) Contrib. Embryol., Carnegie Inst. Wash. Publ. 275, 12: 1-364.

- In this historic 1921 pathology paper, figures and plates of abnormal embryos are not suitable for young students.

1921 Carnegie Collection - Abnormal: Preface | 1 Collection origin | 2 Care and utilization | 3 Classification | 4 Pathologic analysis | 5 Size | 6 Sex incidence | 7 Localized anomalies | 8 Hydatiform uterine | 9 Hydatiform tubal | Chapter 10 Alleged superfetation | 11 Ovarian Pregnancy | 12 Lysis and resorption | 13 Postmortem intrauterine | 14 Hofbauer cells | 15 Villi | 16 Villous nodules | 17 Syphilitic changes | 18 Aspects | Bibliography | Figures | Contribution No.56 | Contributions Series | Embryology History

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |