Book - An Atlas of Topographical Anatomy 6

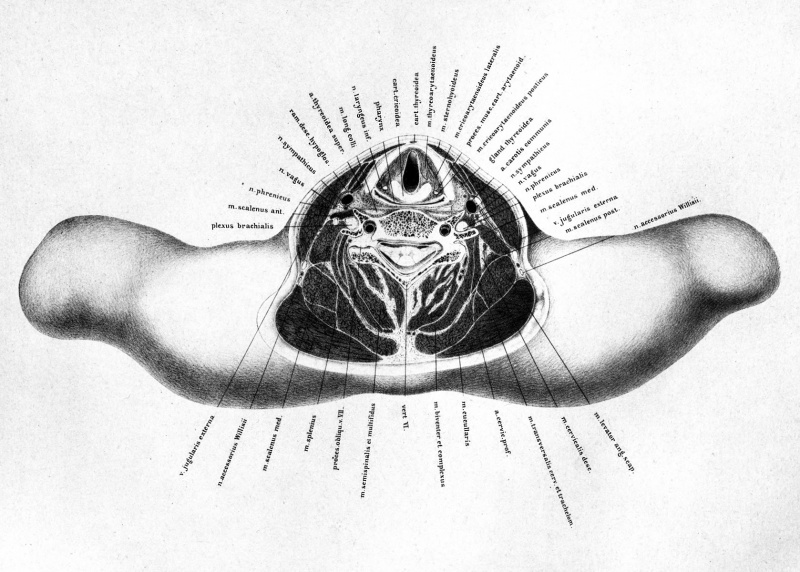

VI. Transverse section of the same body through the neck at the level of the cricoid cartilage and sixth cervical vertebra

| Embryology - 18 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

Braune W. An atlas of topographical anatomy after plane sections of frozen bodies. (1877) Trans. by Edward Bellamy. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

- Plates: 1. Male - Sagittal body | 2. Female - Sagittal body | 3. Obliquely transverse head | 4. Transverse internal ear | 5. Transverse head | 6. Transverse neck | 7. Transverse neck and shoulders | 8. Transverse level first dorsal vertebra | 9. Transverse thorax level of third dorsal vertebra | 10. Transverse level aortic arch and fourth dorsal vertebra | 11. Transverse level of the bulbus aortae and sixth dorsal vertebra | 12. Transverse level of mitral valve and eighth dorsal vertebra | 13. Transverse level of heart apex and ninth dorsal vertebra | 14. Transverse liver stomach spleen at level of eleventh dorsal vertebra | 15. Transverse pancreas and kidneys at level of L1 vertebra | 16. Transverse through transverse colon at level of intervertebral space between L3 L4 vertebra | 17. Transverse pelvis at level of head of thigh bone | 18. Transverse male pelvis | 19. knee and right foot | 20. Transverse thigh | 21. Transverse left thigh | 22. Transverse lower left thigh and knee | 23. Transverse upper and middle left leg | 24. Transverse lower left leg | 25. Male - Frontal thorax | 26. Elbow-joint hand and third finger | 27. Transverse left arm | 28. Transverse left fore-arm | 29. Sagittal female pregnancy | 30. Sagittal female pregnancy | 31. Sagittal female at term

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

THIS plate is taken from a section of the same body as the last, and has been prepared in the usual manner.

The section passed through the larynx, and should properly have kept to the plane of the lower vocal cords, but it passed above them in a horizontal direction, and fell on the lower half of the sixth cervical vertebra.

The body has a peculiarly well-arched thorax, and owing to the great muscular development, the shoulders are high up, and although there are the normal number of vertebra the neck appears short, corresponding in the most marked degree with the male type of neck formation. Here again the section does not show a circular contour, but rather a prismatic one. It is easily seen that this is owing, to a great extent, to the powerful muscular development of the sterno-cleido-mastoids and the trapezii.

As the section has not passed through the head of the humerus, but through the acromio-clavicular articulation, it did not traverse the shoulders at their greatest breadth, but at the junction of the regions of the neck and shoulder. Therefore the lateral portions of the plate represent only the upper portion of the roundness of the shoulder, the supplementary parts of which will be shown in following plates.

The slight irregularity noticed in the edges is owing to loss of substance after the use of the saw.

In the female, or slightly developed male subject, the lamina, which in this case was about 0.4 in. thick, would have taken a totally different form, as the position of the shoulder would be lower in the so-called cylindrical portion of the neck, and consequently exhibit no lateral expansion in the region of the junction of the shoulder and neck, the upper surface of such a section, however, would offer another shape, and approximate more to the circular. Pirogoff's plate (fasc. i, tab. x, fig. 5) should be examined in order to prove that it is the feebly-developed muscular neck which takes the circular form. Pirogoff, moreover, says that his section was taken from an emaciated body ; however, I maintained from recent sections on a man of fifty years of age (such as is represented in Tab. ix of the first volume), that a section at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra is tolerably round. The present case must then be regarded as typical of the neck of a young powerful male, and deviations towards the circular form on the living body are to be referred to want of muscular development.

Sections on unhardened bodies naturally give no fixed forms corresponding with their original relations. The parts yield so much on bodies which have been frozen and subsequently thawed that the neck gradually acquires a circular shape. This may very likely be the reason that the plates of Beraud and Nuhn, which represent very similar regions of the neck, differ so essentially from mine as regards external form. (Beraud's plate is in his 'Atlas d'Anatomie Chirurgicale,' Paris, 1862, pi. xxxvii. Nuhn's is represented by Henle, 4 Muskellehre,' p. 131, and by Henke, ' Abl. der Topographischen Anatomie,' taf. Ixix.)

As to individual portions of the present plate to be studied, the first of all is the larynx, which is divided close below the vocal cords ; anteriorly is the arc, formed by the section of the thyroid cartilage, and close behind it the section of the cricoid. Of the arytenoid cartilages only the muscular processes are met with, and nothing is seen of the vocal processes, as they lie higher. The space between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages is filled up with the thyro-artenoideus and crico-arytenoideus lateralis. On the other side are some fasciculi of the thyro-epiglottideus. Behind this and on the anterior surface of the crico-arytenoidei postici lie the inferior laryngeal nerve and artery.

From the form of the transversely divided trachea it will be observed that the section does not pass far below the rima glottidis, and that the surface of the cricoid cartilage is divided obliquely forwards and downwards. The space expands still wider further downwards, and changes its laterally compressed form for that of a cylinder, as far as to the point where the cricoid cartilage encloses it completely. Finally, in the trachea it becomes in section a segment of a circle.

As the present plate offers no points of great interest as regards the relations of the larynx, I have made on a preparation hardened in alcohol, a section exactly in the plane of the vocal cords and introduced it in the accompanying woodcut. It will be seen that FIG. 11.

the processus vocales are continuous immediately with the elastic fibres of the vocal cords. At the line of section, which is not sharply defined, some reticulated cartilage exists. In front the vocal cords pass into a roll of connective tissue to which the thyroarytenoid muscles are attached. The mucous membrane on the vocal cords is destitute of ciliated epithelium, 'and is stretching tightly over and is firmly attached to them. Beneath the mucous membrane the glands in this plane lie in the angle between the anterior extremities of the vocal cords and between the arytenoid cartilages posteriorly. On either side of the vocal cords are seen the two cut surfaces of the thyro-arytenoidei, of which the median is shown as internal and the lateral as external. Still more externally are the cut fibres of a muscle which passes partly to the thyroid cartilage and partly to the epiglottis, the thyro-aryteno-epiglottideus (Henle). Behind the section of the arytenoid cartilage the arytenoideus is seen in section passing across from one cartilage to the other. Referring again to the large plate, we see behind the cricoid cartilage and behind the section of the crico-arytenoideus posticus, the transverse chink of the pharynx. The section shows it empty, therefore its anterior and posterior walls are in contact ; behind it is the middle portion of the inferior constrictor of the pharynx. As the pharynx lies immediately upon the vertebrse, and the longus colli and recti capitis postici majores, the space required by the morsel of food in passing downwards is provided for by the dragging forward of the anterior wall of the pharynx and the advancement of the larynx. The larynx is, moreover, lifted in swallowing. The result of this twofold change in position is a movement of the larynx towards the chin, which can be easily observed during the act of deglutition. The lax cellular tissue which lies between the pharynx and the vertebrae appears in the section as a narrow border, and by its extraordinary looseness it permits of the movements of the pharynx upon the vertebrae. But it is of such a nature that haemorrhage into it would cause great distension. This condition is, moreover, favorable to the infiltration of pus.

Behind the pharynx lies the section of the sixth cervical vertebra, which has been divided in its lower half. As the section fell to the right side, and exactly at the springing of its arch, a clear view is furnished of the lumen of the spinal canal, which has the form of an equilateral triangle, and is so spacious that in the most extensive movements of the cervical vertebrae the spinal cord has free room, and is thoroughly protected from strain.

The relation of the vertebra to the surrounding soft parts is worthy of notice, inasmuch as it appears to be pushed remarkably forwards. If half the diameter, for instance, be taken from before backwards, the body of the vertebra would lie completely in the anterior half of the section. By comparing the measurements with those of the section shown in Plate I, and also in the other figures, it is seen that this position of the vertebra is correct. This appearance is owing to the cervical curvature of the spinal column. The distance of the medulla from the surface of the neck on the living body is usually represented as far too slight. Very similar relations will be found in Pirogoff (fasc. i, tab. iii, fig. 2 ; tab. ii, fig. 1 ; fasc. i, tab. x, fig. 66).

As the body of the vertebra is cut through near its lower border, its connection with the transverse process is clear. The vertebral artery full of injection, with its satellite vein, is seen in the bony canal on either side. On the left side, the section has fallen rather deeper, so that the canal in the transverse processes is closed in posteriorly merely by ligamentous tissue; it involves also the superior articular process of the seventh cervical vertebra and its joint cavity. Since the body of the sixth cervical vertebra with its transverse process is divided, a proper opportunity is afforded of examining the so-called tubercle of Chassaignac and its relation to the common carotid artery. Among surgeons this process is known as Chassaignac's tubercle, and is considered, according to the statements of authors, to be a most valuable landmark in seeking the vessel, in cases where ligature is rendered difficult on account of swelling of the tissues or the presence of a tumour.

It is clearly seen that the anterior of the tubercles of the bifurcated transverse process, which proceeds from the side of the body of the vertebra, and encloses the sixth cervical nerve, is a direct guide to the common carotid artery, which lies immediately upon it. Further, with regard to this tubercle, it has a morphological importance as a rudimentary rib, and is correctly called the eminentia costaria, jutting out more markedly from the sixth vertebra than from any of the others. It can be readily felt in the living body if gentle pressure be made on the side of the body of the vertebra upwards towards the level of the larynx.

Although advantage may be taken of the presence of this tubercle in looking for the vessel, for the sake of demonstration, and of making beginners acquainted with its locality, still it is not necessary for surgeons of experience to avail themselves of such a means of assistance, even in complicated cases. If the vessel has to be ligatured exactly at this spot, it is better to make the usual dissection over the course of the artery, dividing layer by layer. In this way there is less danger of wounding important parts, whilst the course to the vessel is sure.

The position of the vessels is denned by muscles and fasciae, but these can be easily pushed away from their relations with the bony points. When, however, the vessels lie in bony canals, and are enclosed as fixedly and unalterably as the vertebral, for instance, then undoubtedly the determination of their position is facilitated. But, on the other hand, the means of reaching them may be rendered proportionately difficult. As, however, the carotid can be easily drawn away from its relation to Chassaignac's tubercle, this prominence as a means of assistance is not directly suitable in all cases, as is already proved by examination of the normal thyroid body (see figure), the upper lobe of which lies between the artery and the thyroid cartilage. Swellings of this gland must draw the artery away from the bony prominence, but they do not permit of its being released from the strong fibrous sheath, which is formed by the investment of the sterno-cleido-mastoid and scalene muscles, and of the gland itself.

From a section which I made at a similar level in the neck on a well-frozen body affected with goitre, the carotid was half an inch external to the tubercle in question, but the relations of the muscle and fasciae were unaltered. On a closer examination of the plate the relation of the fasciae to the artery will be seen. It is true that such representations are insufficient ; and in order to make clear the relations of all the fasciae one is compelled to represent them as white lines. I have therefore been able to mark out satisfactorily the coalescence of the several laminae. Moreover, actual fasciae cannot be properly distinguished from layers of cellular tissue. For the more accurate relations of this part I refer to the works of Dittl, Pirogoff, and Henle. I may add that the contours of the muscles which chiefly determine the arrangement of fasciae are sufficiently accurately represented in the preparation, and in this respect furnish trustworthy points of reference.

Externally, and somewhat behind the artery, is the internal jugular vein, and between these vessels is the vagus, which in ligature of the artery must be carefully protected from injury. It is moist safely avoided, if after division of the fibrous sheath a fine director be passed through the cellular tissue immediately over the artery, and then the edges of the fascia pulled aside with two pairs of forceps, before passing the ligature needle. By this means the ligature can be as readily applied, either from without inwards or from within outwards. Behind, and nearer the artery, is the sympathetic nerve, which may be avoided if merely the old rule be followed with respect to the vagus, of introducing the needle from without inwards. Behind the vagus, and on the anterior scalene muscle, lies the phrenic nerve.

Behind the jugular vein, between the sterno-cleido-mastoid and the middle scalene muscles, are the supra-clavicular twigs from the fourth cervical nerve.

Between the anterior and middle scalene muscles are the sections of the fifth and sixth cervical nerves, which are figured collectively on the plate as brachial plexus, so as not to disturb the detail of the clearness of the drawings. The seventh cervical nerve comes off from the spinal cord in the vertebral canal, and takes a direction outwards and backwards behind the vertebral artery.

The above-mentioned figures of Nuhn (' Chirurg. Anat. Tafeln.,' tat', iv, fig. 2) and Beraud (' Atlas d'Anat. Chirurg.,' Plate XXXVII, fig. 2) should be compared, as the question to be proved is whether in these plates of sections of the neck the natural relations are represented, since they show not round but polygonal contours. There is one word to be added here on the relations of this section with respect to the vertebra, in order that no misconception may arise : Nuhn's section of the larynx is taken almost at the same level as mine, whilst in Beraud's nothing of the trachea below the cricoid cartilage is seen. Both authors make the corresponding vertebra the fourth cervical, whereas in mine the sixth is shown. One might easily conjecture, therefore, that I have represented a wrong vertebra an error which may be easily committed if one has been already making many sections of the neck. I, however, expressly state that I went to work most accurately in the definition of the vertebra, and believe that I have made no mistake in the accompanying plate.

By comparing the vertical sections on PI. I and II, as Pirogoff gives it, the fourth cervical vertebra is on the level of the epiglottis, and the seventh has the flat surface of the cricoid cartilage in front of it, which also in this particular agrees with my plate. It cannot be disputed that other variations in this respect happen to the extent of the level of a vertebra. These variations are in all probability occasioned by the different degree of curvature of the cervical spine. Nevertheless, I do not think that this change in position can be extended to two vertebrae, and I maintain that Beraud's statement that the fourth cervical vertebra lies deeper than the cricoid cartilage is not correct. There is a vertical section in Beraud's atlas (PI. XXVIII, fig. 2) which bears out my statement. Perhaps, therefore, the parts were pushed out of their places in making a section of a soft preparation.

Pirogoffs transverse sections of the regions of the neck (fasc. i, tab. x) coincide with my account. The cricoid cartilage here lies in front of the sixth cervical vertebra.

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

- Braune Plates (1877): 1. Male - Sagittal body | 2. Female - Sagittal body | 3. Obliquely transverse head | 4. Transverse internal ear | 5. Transverse head | 6. Transverse neck | 7. Transverse neck and shoulders | 8. Transverse level first dorsal vertebra | 9. Transverse thorax level of third dorsal vertebra | 10. Transverse level aortic arch and fourth dorsal vertebra | 11. Transverse level of the bulbus aortae and sixth dorsal vertebra | 12. Transverse level of mitral valve and eighth dorsal vertebra | 13. Transverse level of heart apex and ninth dorsal vertebra | 14. Transverse liver stomach spleen at level of eleventh dorsal vertebra | 15. Transverse pancreas and kidneys at level of L1 vertebra | 16. Transverse through transverse colon at level of intervertebral space between L3 L4 vertebra | 17. Transverse pelvis at level of head of thigh bone | 18. Transverse male pelvis | 19. knee and right foot | 20. Transverse thigh | 21. Transverse left thigh | 22. Transverse lower left thigh and knee | 23. Transverse upper and middle left leg | 24. Transverse lower left leg | 25. Male - Frontal thorax | 26. Elbow-joint hand and third finger | 27. Transverse left arm | 28. Transverse left fore-arm | 29. Sagittal female pregnancy | 30. Sagittal female pregnancy | 31. Sagittal female at term

Reference

Braune W. An atlas of topographical anatomy after plane sections of frozen bodies. (1877) Trans. by Edward Bellamy. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 18) Embryology Book - An Atlas of Topographical Anatomy 6. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Book_-_An_Atlas_of_Topographical_Anatomy_6

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G