Abnormal Development - Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects

Introduction

In 2001, the Australian estimated birth prevalence of neural tube defects was 0.5 per 1,000 births (National Perinatal Statistics Unit). Low maternal dietary folic acid (folate) has been shown to be associated with the development of neural tube defects. In September 2009, mandatory folic acid fortification of bread flour was introduced in Australia.

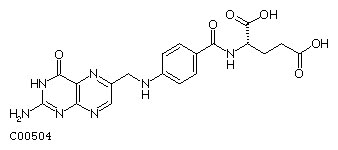

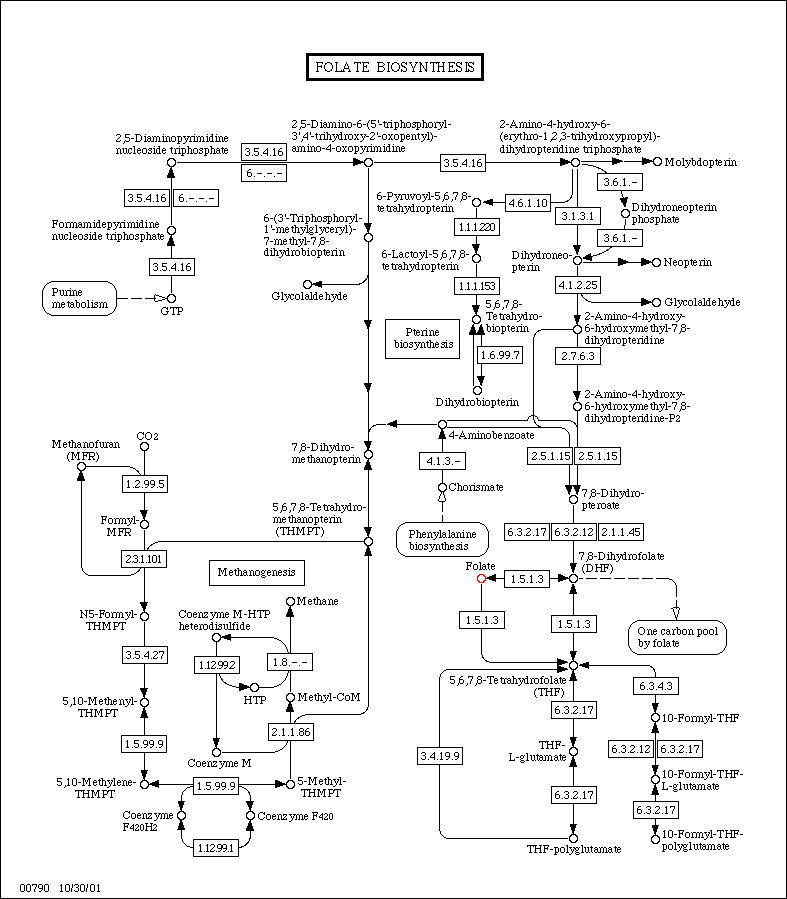

Research over the last 20 years had suggested a relationship between maternal diet and the birth of an affected infant. Recent evidence has confirmed that folic acid, a water soluble vitamin (vitamin B9) found in many fruits (particularly oranges, berries and bananas), leafy green vegetables, cereals and legumes, may prevent the majority of neural tube defects.

|

|

In the U.S.A. the Food and Drug Administration in 1996 authorized that all enriched cereal grain products be fortified with folic acid, with optional fortification beginning in March 1996 and mandatory fortification in January 1998.

The March of Dimes Folic Acid Campaign (a major US charity group) has as one of its major objectives to reduce neural tube defects by 30% by 2001 using community programs, professional education, and mass media information.

Some Recent Findings

|

Neural Tube Defect Classification

Neural tube defects comprise three distinct conditions: anencephaly, spina bifida and encephalocele.

Anencephaly

- A congenital anomaly characterised by the total or partial absence of the cranial vault, the covering skin and the brain.

- Remaining brain tissue may be very much reduced in size.

- Craniorachischisis and iniencephaly are included.

- Acephaly, the absence of the head observed in amorphous acardiac twins, is excluded.

- ICD codes: ICD-9-BPA codes: 740.00–740.29 or ICD-10-AM codes: Q00.0–Q00.2.

Spina bifida

- A congenital anomaly characterised by a failure in the closure of the spinal column.

- Characterised by herniation or exposure of the spinal cord and/or meninges through the incompletely closed spine.

- This excludes spina bifida occulta and sacrococcygeal teratoma without dysraphism.

- ICD codes: ICD-9-BPA codes: 741.00–741.99 or ICD-10-AM codes: Q05.0–Q05.9.

Encephalocele

- A congenital anomaly characterised by herniation of the brain and/or meninges through a defect in the skull.

- ICD codes: ICD-9-BPA codes: 742.00–742.09 or ICD-10-AM codes: Q01.0–Q01.2, Q01.8, Q01.9.

Australian Statistics

- Women who have one infant with a neural tube defect have a significantly increased risk of recurrence

- 40-50 per thousand compared with 2 per thousand for all births.

- A randomised controlled trial conducted by the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom demonstrated a 72% reduction in risk of recurrence by periconceptional (ie before and after conception) folic acid supplementation (4mg daily).

- Other epidemiological research, including work done in Australia, suggests that primary occurrences of neural tube defects may also be prevented by folic acid either as a supplement or in the diet.

- This has been confirmed in a randomised controlled trial from Hungary, which found that a multivitamin supplement containing 0.8mg folic acid was effective in reducing the occurrence of neural tube defects in first births.

Before mandatory folic acid fortification was introduced:

- mean dietary folic acid intakes for women aged 16–44 years (the target population) in Australia was 108 micrograms (μg) of folic acid per day and in New Zealand was 62 μg of folic acid per day, well below the recommended 400 μg per day.

- there were 149 pregnancies affected by NTDs in 2005 in Australia (rate of 13.3 per 10,000 births) in the three states that provide the most accurate baseline of NTD incidence (South Australia, Western Australia and Victoria), and 63 pregnancies affected by NTDs in 2003 in New Zealand (rate of 11.2 per 10,000 births).

Before mandatory iodine fortification was introduced:

- large proportions of the Australian and New Zealand population had inadequate iodine intakes.

- national surveys measuring median urinary iodine concentration (MUIC) in schoolchildren, an indicator of overall population status, confirmed mild iodine deficiency in both countries.

- The concentration was 96 μg per litre in Australia, and 66 μg per litre in New Zealand, less than the 100–200 μg per litre considered optimal.

USA Statistics

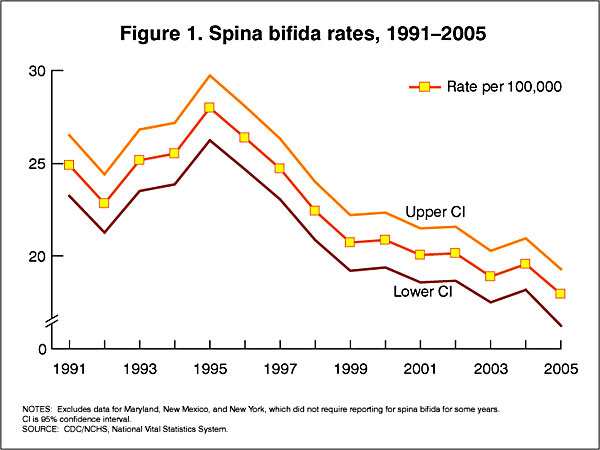

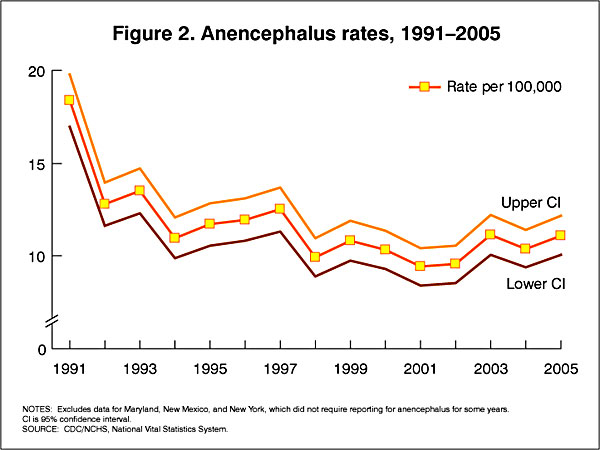

In the U.S.A. the Food and Drug Administration in 1996 authorized that all enriched cereal grain products be fortified with folic acid, with optional fortification beginning in March 1996 and mandatory fortification in January 1998. The data below shows the subsequent changes in anencephaly and spina bifida rate over that period.

Data CDC Report[8]

Folic Acid

Formula: C19H19N7O6

Alternate Names: Folic acid, Folate, Pteroylglutamic acid

(Data from KEGG)

Folate Supplementation and Other Abnormalities

A recent study of periconceptional folate supplementation using the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (July 2010) identified no statistically significant evidence of any effects on prevention of cleft palate, cleft lip, congenital cardiovascular defects, miscarriages or any other birth defects.[9]

Australian NHMRC

The Australian NHMRC (1988) recommends neonates be assessed for follow-up care under the following conditions.

- Birthweight less than 1500g or gestational age less than 32 weeks

- Small-for-gestational-age neonates

- Perinatal asphyxia

- Apgar score less than 3 at 5 minutes

- clinical evidence of neurological dysfunction

- delay in onset of spontaneous respiration for more than 5 minutes and requiring mechanical ventilation

- Clinical evidence of central nervous system abnormalities ie., seizures, hypotonia

- Hyperbilirubinaemia of greater than 350umol/l in full term neonates

- Genetic, dysmorphic or metabolic disorders or a family history of serious genetic disorder

- Perinatal or serious neonatal infection including children of mothers who are HIV positive

- Psychosocial problems eg., infants of drug-addicted or alcoholic mothers.

References

- ↑ <pubmed>22480165</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>22333513</pubmed>

- ↑ AIHW National Perinatal Statistics Unit 2011. Neural tube defects in Australia: prevalence before mandatory folic acid fortification. Cat. no. PER 53. Canberra: AIHW. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737420864

- ↑ <pubmed>20649773</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20655945</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20683905</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21254354</pubmed>

- ↑ CDC Trends in Spina Bifida and Anencephalus in the United States, 1991-2005

- ↑ <pubmed>20927767</pubmed>

Reviews

<pubmed>16631914</pubmed> <pubmed>16685040</pubmed> <pubmed>15937577</pubmed>

Articles

<pubmed>11887752</pubmed> <pubmed>7474275</pubmed> <pubmed>68194</pubmed> <pubmed>1015847</pubmed>

Search PubMed

Search Bookshelf: Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects | Folic Acid

- Folic Acid Supplementation for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects An Update of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

- Screening for Neural Tube Defects— Including Folic Acid/Folate Prophylaxis Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2nd Edition: 1996

Search Pubmed: Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects | Folic Acid

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

- Australia Department of Health Nutrition and Healthy Eating Trends in Neural Tube Defects in Australia

- See also the NHMRC Publication Dietary Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects

- National Perinatal Statistics Unit

- Australian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics

- Australian Nutrition Foundation

- CSIRO Human Nutrition

- Food, Nutrition & Health Information - Centre for Advanced Food Research

- Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health (USA)Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Folate

- Foodwatch

- Healthy Eating, Healthy Living

- AIS Sport Nutrition - information from the Australian Institute of Sport. Supplies nutrition research, a question-and-answer section, publications, and other resources.

- America's Eating Habits - a report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's economic research service. Covers dietary recommendations, health claims in food advertising, reality about cholesterol, and various other topics.

- British Nutrition Foundation - an organization that works with academic, private, and public groups on nutrition. Includes nutrition education, facts, news, and publications.

- Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition - a repository of links relevant to all manner of food issues, including food safety. Emphasizes FDA regulations and related research programs.

- Nutrition.gov - a collection of information and links to other sites on food safety, food programs, and federally funded research centers.

- Nutrition.org - site of the American Society for Nutritional Sciences. Features an encyclopedia that summarizes food sources, diet recommendations, and deficiencies for a number of macro- and micronutrients.

- Nutrition Navigator - a guide to nutrition websites reviewed and rated by Tufts University nutritionists. Supplies news and sections arranged by topic.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture

- Children's Nutrition Research Center

- Facts about the DASH Diet

- Healthfinder Kids

- Interactive Healthy Eating Index

- National Dairy Council

- Nutrition Explorations

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 23) Embryology Abnormal Development - Folic Acid and Neural Tube Defects. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Folic_Acid_and_Neural_Tube_Defects

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G