Abnormal Development - Ectopic Implantation: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 244: | Line 244: | ||

==International Classification of Diseases== | ==International Classification of Diseases== | ||

Revision as of 12:32, 1 June 2019

| Embryology - 16 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

| ICD-11 |

|---|

JA01 Ectopic pregnancy

|

Introduction

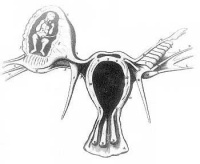

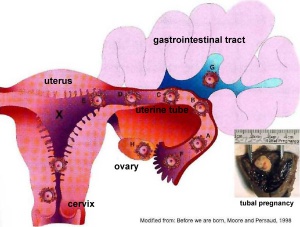

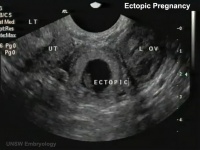

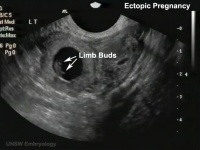

Ectopic implantation or ectopic pregnancy (Greek, ektopos = "out of place") refers to the abnormal implantation of the blastocyst. Implantation of the blastocyst normally occurs within the body of the uterus, also called eutopic implantation. Ectopic implantation can occur at number of sites outside the uterine body. The most common form of human ectopic pregnancy is when implantation occurs within the uterine tube, described as a tubal pregnancy. Note that the endocrine signals blocking the menstrual cycle and indicating a pregnancy will still be released following this ectopic implantation. Ectopic pregnancies are therefore often identified by early ultrasound scans.

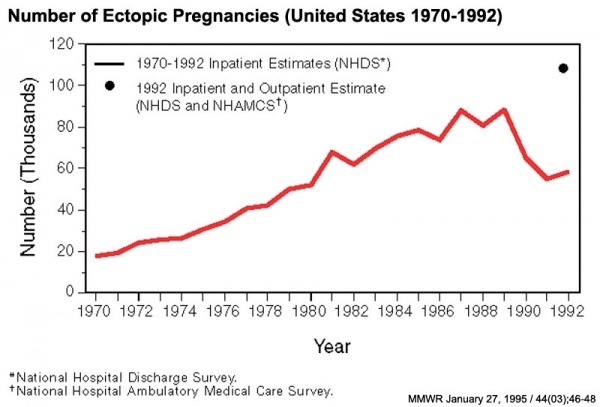

Ectopic pregnancy is also a high-risk maternal medical condition with an approximate incidence of 1.5 to 2 % in reported pregnancies. There is some indication that the incidence may be increasing (United States has increased from 4.5 per 1,000 pregnancies in 1970 to an estimated 19.7 per 1,000 pregnancies in 1992[1])

The risk factors for tubal ectopic pregnancy include: tubal damage by infection (particularly Chlamydia trachomatis) or surgery, smoking and in vitro fertilization therapy. Prolonged tubal damage is often described as pelvic inflammatory disease and "scarring" can affect the cilia-mediated transport of the blastocyst during the first week of development.

This is also the most common cause of pregnancy-related deaths in the first trimester. A recent United Kingdom enquiry into maternal deaths[2], identified ectopic pregnancy as the fourth most common cause of maternal death (73% of early pregnancy deaths).

Ectopic sites are named according to the anatomical location: Tubal (Ampullary, Isthmic, Cornual), Cervical and Ovarian. A study of 1800 surgically treated ectopics between 1992 and 2001 identified implantation sites by frequency: interstitial (2.4%), isthmic (12.0%), ampullary (70.0%), fimbrial (11.1%), ovarian (3.2%) or abdominal (1.3%).[3]

| Ectopic Links: ectopic pregnancy | implantation | Week 2 | placenta abnormalities | trophoblast | uterus | Chlamydia | Ultrasound - Ectopic Pregnancy | ultrasound | Ectopic Implantation Research | |||

|

Some Recent Findings

|

| More recent papers |

|---|

|

This table allows an automated computer search of the external PubMed database using the listed "Search term" text link.

More? References | Discussion Page | Journal Searches | 2019 References | 2020 References Search term: Ectopic Pregnancy | Tubal Pregnancy |

| Older papers |

|---|

| These papers originally appeared in the Some Recent Findings table, but as that list grew in length have now been shuffled down to this collapsible table.

See also the Discussion Page for other references listed by year and References on this current page.

|

About Uterine Tube Anatomy

Anatomy - there are 3 main parts (regions) to the uterine tube:

- isthmus - closest to the uterus (body)

- ampulla - middle region, more dilated in diameter and most common site for fertilization.

- infundibulum - furthest from the uterus ending in the fimbriae and open to the peritoneum

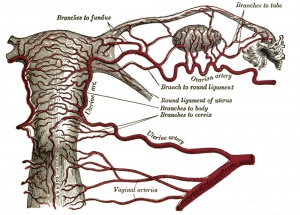

Blood Supply - arterial supply is from branches of the uterine and ovarian arteries, these small vessels are located within the mesosalpinx (part of the lining of the abdominal cavity).

Lymphatic drainage - through the iliac and lateral aortic nodes.

Innervation - has both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. Sensory fibres from thoracic segments (T11-T12) and the first lumbar segment (L1).

Ultrasound Ectopic Implantation

| Tubal Ectopic | Bicornuate Uterus Ectopic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Links: Ectopic Implantation | Ultrasound

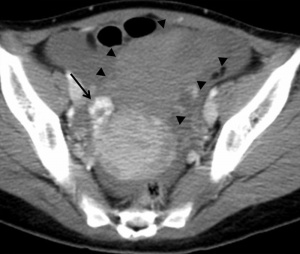

Computed Tomography Ectopic Implantation

Computed Tomography imaging findings of a 37-year-old woman with interstitial pregnancy.[8] Showing initial CT detection and a subsequent scan following rupture causing a hematoma around uterus and a massive hemoperitoneum.

Initial CT - gestational sac |

Follow-up CT - massive hemoperitoneum |

CT - hematoma around uterus |

- Links: Computed Tomography

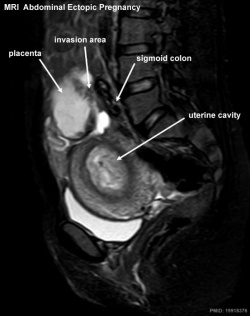

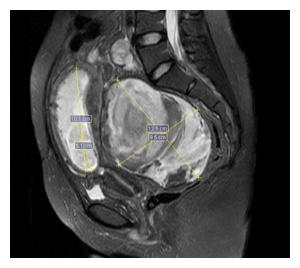

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Abdominal Ectopic Implantation

2W SPAIR sagittal MRI of lower abdomen demonstrating the placental invasion.[9]

|

|

- Links: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Statistics

Australia

Rates of pelvic inflammatory disease and ectopic pregnancy in Australia, 2009-2014[4]

- "To analyse yearly rates of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and ectopic pregnancy (EP) diagnosed in hospital settings in Australia from 2009 to 2014. METHODS: We calculated yearly PID and EP diagnosis rates in three states (Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland) for women aged 15-44 years using hospital admissions and emergency department (ED) attendance data, with population and live birth denominators. ...For EP, in 2014 the rate of all admissions was 17.4 (95% CI 16.9 to 17.9) per 1000 live births and of all ED presentations was 15.6 (95% CI 15.1 to 16.1). Comparing 2014 with 2009, the rates of all EP admissions (aIRR 1.06, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.08) and rates in EDs (aIRR 1.24, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.31) were higher. PID and EP remain important causes of hospital admissions for female STI-associated complications. Hospital EDs care for more PID cases than inpatient departments, particularly for young women."

- Links: Australian statistics | bacterial infection

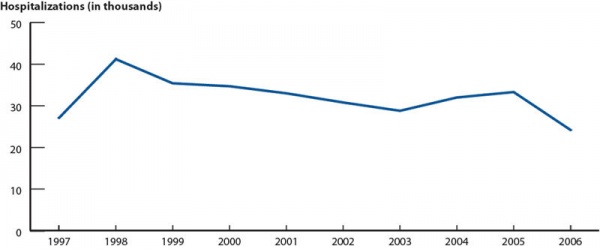

USA

Ectopic Pregnancies- United-States 1970-1992[1]

- Links: USA

Ectopic Pregnancy Histology

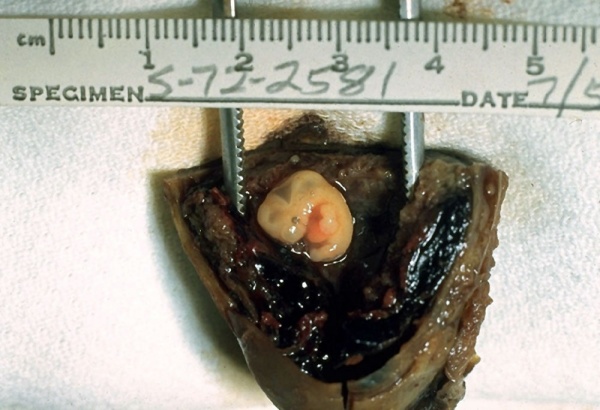

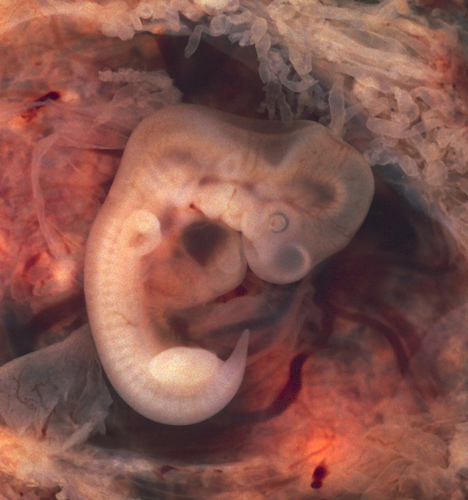

CDC Image by Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr., 1972

Ed Uthman Image (pathologist in Houston, Texas) section of ectopic (tubal) pregnancy about Carnegie stage 7 in Week 3.

Image version links: ExtraLarge 1712x1206px | Large 1024x721px | Medium 500x352px

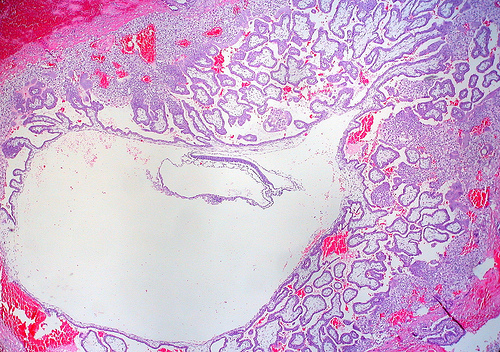

Ed Uthman Image (pathologist in Houston, Texas) image of of ectopic (tubal) pregnancy about Carnegie stage 15 in Week 5.

Image version links: ExtraLarge 1874 x 2000px | Large 959 x 1024px | Medium 468 x 500px

Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy

| Chlamydia infections (Chlamydia trachomatis) are the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection, often undiagnosed and asymptomatic. The infections can ascend the female genital tract, colonizing the endometrial mucosa, then the uterine tubes. This type of infection is described as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). |

Interstitial Pregnancy

| (cornual pregnancy) A less common type 2 to 4% of ectopic pregnancies. The gestation develops in the uterine portion of the fallopian tube lateral to the round ligament. |  Interstitial ectopic pregnancy[10] |

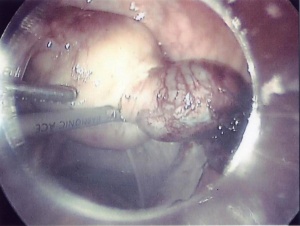

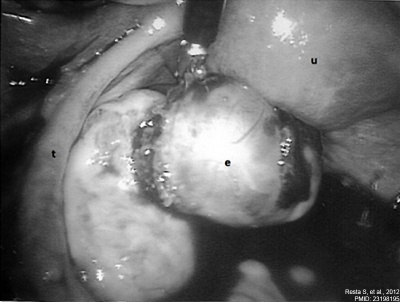

Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy

| Clinical operative photograph at the beginning of the procedure of the laparoscopic treatment of the ovarian pregnancy.

|

Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy[11] |

Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy

This form of ectopic pregnancy is a rare high-risk condition and represents less than 1% of all ectopic pregnancies. The reported incidence varies between 1:1,000 to 1:18,000.

Rudimentary Horn Pregnancy

A rare types of ectopic pregnancy (about 1 in 76,000 pregnancies) in most cases the horn is non-communicating. Therefore fertilisation probably occurs by transperitoneal migration. This form untreated can also lead to uterine rupture.

Caesarean Scar Pregnancy

Caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is a rare types of ectopic pregnancy (about 1 in 2000 pregnancies), but probably increasing as caesarean rates rise. The gestation is completely surrounded by both myometrium and fibrous tissue of the caesarean section scar and separated from the endometrial cavity and endocervical canal.

A recent review of 17 studies (69 cases of CSP managed expectantly, 52 with and 17 without embryonic/fetal heart beat)[13]

| Caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) | |

| with embryonic/fetal heart activity | without embryonic/fetal cardiac activity |

|---|---|

|

|

Heterotopic Pregnancy

(Greek, heteros = other) Clinical term for a very rare pregnancy of two or more embryos, consisting of both a uterine cavity embryo implantation and an ectopic implantation. The ectopic implantation usually identified by prenatal scanning as occurring within the uterine tube (tubal pregnancy) though has also been identified as abdominal pregnancies.[14][15]

Ectopic Molar Pregnancy

Left-sided unruptured ampullary ectopic pregnancy at laparoscopy.[16]

- Links: Hydatidiform Mole

Ruptured Ectopic

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy[17]

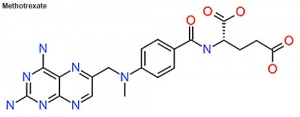

Methotrexate

(MTX, amethopterin) Drug with several different uses including the treatment of ectopic pregnancy[18] and for the induction of medical abortions. Acts as a antimetabolite and antifolate (folic acid antagonist) drug that inhibits DNA synthesis in actively dividing cells, including trophoblasts, and therefore has other medical uses include cancer and autoimmune disease treatment. Treatment success in ectopic pregnancy relates to serum β human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) concentration.

- Links: Medline Plus

International Classification of Diseases

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (1995). Ectopic pregnancy--United States, 1990-1992. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. , 44, 46-8. PMID: 7823895

- ↑ Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (CEMD) Why Mothers Die 2000–2002 PDFPDF2

- ↑ Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, Pouly JL & Job-Spira N. (2002). Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10 year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum. Reprod. , 17, 3224-30. PMID: 12456628

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Goller JL, De Livera AM, Guy RJ, Low N, Donovan B, Law M, Kaldor JM, Fairley CK & Hocking JS. (2018). Rates of pelvic inflammatory disease and ectopic pregnancy in Australia, 2009-2014: ecological analysis of hospital data. Sex Transm Infect , , . PMID: 29720385 DOI.

- ↑ Hamed HO, Ahmed SR & Alghasham AA. (2012). Comparison of double- and single-dose methotrexate protocols for treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet , 116, 67-71. PMID: 22035883 DOI.

- ↑ Shavell VI, Abdallah ME, Zakaria MA, Berman JM, Diamond MP & Puscheck EE. (2012). Misdiagnosis of cervical ectopic pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. , 285, 423-6. PMID: 21748311 DOI.

- ↑ Shao R. (2010). Understanding the mechanisms of human tubal ectopic pregnancies: new evidence from knockout mouse models. Hum. Reprod. , 25, 584-7. PMID: 20023297 DOI.

- ↑ Shin BS & Park MH. (2010). Incidental detection of interstitial pregnancy on CT imaging. Korean J Radiol , 11, 123-5. PMID: 20046504 DOI.

- ↑ Yildizhan R, Kolusari A, Adali F, Adali E, Kurdoglu M, Ozgokce C & Cim N. (2009). Primary abdominal ectopic pregnancy: a case report. Cases J , 2, 8485. PMID: 19918376 DOI.

- ↑ Walid MS & Heaton RL. (2010). Diagnosis and laparoscopic treatment of cornual ectopic pregnancy. Ger Med Sci , 8, . PMID: 20725587 DOI.

- ↑ Resta S, Fuggetta E, D'Itri F, Evangelista S, Ticino A & Porpora MG. (2012). Rupture of Ovarian Pregnancy in a Woman with Low Beta-hCG Levels. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol , 2012, 213169. PMID: 23198195 DOI.

- ↑ Mohebbi MR, Rosenkrans KA, Luebbert EE, Hunt TT & Jung MJ. (2011). Ectopic pregnancy in the cervix: a case report. Case Rep Med , 2011, 858241. PMID: 22110520 DOI.

- ↑ Calì G, Timor-Tritsch IE, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Monteaugudo A, Buca D, Forlani F, Familiari A, Scambia G, Acharya G & D'Antonio F. (2018). Outcome of Cesarean scar pregnancy managed expectantly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol , 51, 169-175. PMID: 28661021 DOI.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Sun SY, Araujo Júnior E, Elito Júnior J, Rolo LC, Campanharo FF, Sarmento SG, Nardozza LM & Moron AF. (2012). Diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy using ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in the first trimester of pregnancy: a case report. Case Rep Radiol , 2012, 317592. PMID: 23259128 DOI.

- ↑ Gayer G. (2012). Images in clinical medicine. Abdominal ectopic pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. , 367, 2334. PMID: 23234516 DOI.

- ↑ Bousfiha N, Erarhay S, Louba A, Saadi H, Bouchikhi C, Banani A, El Fatemi H, Sekkal M & Laamarti A. (2012). Ectopic molar pregnancy: a case report. Pan Afr Med J , 11, 63. PMID: 22655097

- ↑ Samiei-Sarir B & Diehm C. (2013). Recurrent ectopic pregnancy in the tubal remnant after salpingectomy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol , 2013, 753269. PMID: 24151570 DOI.

- ↑ Stovall TG & Ling FW. (1993). Single-dose methotrexate: an expanded clinical trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , 168, 1759-62; discussion 1762-5. PMID: 8317518

Reviews

Shaw JL, Dey SK, Critchley HO & Horne AW. (2010). Current knowledge of the aetiology of human tubal ectopic pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. Update , 16, 432-44. PMID: 20071358 DOI.

Shao R. (2010). Understanding the mechanisms of human tubal ectopic pregnancies: new evidence from knockout mouse models. Hum. Reprod. , 25, 584-7. PMID: 20023297 DOI.

Corpa JM. (2006). Ectopic pregnancy in animals and humans. Reproduction , 131, 631-40. PMID: 16595714 DOI.

Articles

Exalto N, Vooys GP, Meyer JW & Lange WP. (1980). Ovarian pregnancy: a morphologic description. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. , 11, 179-87. PMID: 7194809

Purslow CE. (1915). Tubal Pregnancy showing Foetus undergoing Dissolution. Proc. R. Soc. Med. , 8, 68. PMID: 19978839

Matsunaga E & Shiota K. (1980). Ectopic pregnancy and myoma uteri: teratogenic effects and maternal characteristics. Teratology , 21, 61-9. PMID: 7385056 DOI.

Search Pubmed

June 2010

- "ectopic pregnancy" All (14958) Review (1350) Free Full Text (1196)

- "tubal pregnancy" All (8010) Review (683) Free Full Text (630)

Search Pubmed: ectopic pregnancy | ectopic implantation | tubal pregnancy | tubal implantation

External Links

External Links Notice - The dynamic nature of the internet may mean that some of these listed links may no longer function. If the link no longer works search the web with the link text or name. Links to any external commercial sites are provided for information purposes only and should never be considered an endorsement. UNSW Embryology is provided as an educational resource with no clinical information or commercial affiliation.

Glossary Links

- Glossary: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | Numbers | Symbols | Term Link

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 16) Embryology Abnormal Development - Ectopic Implantation. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Abnormal_Development_-_Ectopic_Implantation

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G