2011 Group Project 1

| Note - This page is an undergraduate science embryology student group project 2011. |

Turner Syndrome

--Mark Hill 10:44, 8 September 2011 (EST) Some of the existing sub-sections have appropriate content, but there are also empty sub-sections, a total lack of referencing/citation and no glossary.

- The referencing issue needs urgent progress.

- Existing figures/table are appropriate. Table appears to be directly used from an uncited source.

- There needs to be more images in this work.

- Where is the student drawn figure?

- Read http://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php?title=Help:Reference_Tutorial#Multiple%20Instances%20on%20Page

Introduction

Turner syndrome, named after Henry Hubert Turner who first described the syndrome in his paper in 1938,[1] is one of the most commonly occuring chromosomal disorders. It is caused by complete or partial X monosomy in some or all cells and occurs in approximately 1 in 2000 live female births, however the morbidity rate of spontaneous abortions is 10% and only about 1% of fetuses survive to term.

During normal fetal development, each ovary contain as many as 7 million oocytes. The oocytes gradually reduced to 400,000 during menarche and during menopause fewer than 10,000 remains. However, in Turner syndrome, the ovaries develop normally during embryogenesis but the absence of the second X chromosome leads to an accelerated loss of oocytes, which is complete by the time the infant, is aged 2. Genetically menopause occurs before menarche and the ovaries are reduced to atrophic fibrous strands, devoid of ova and follicles (streak ovaries). Development of somatic (nongonadal) tissues that reside on the missing/abnormal X chromosome are also severely affected. For example short stature is caused by a deletion of the Xp chromosome and the deletion of Xq causes gonadal dysfunction [2].

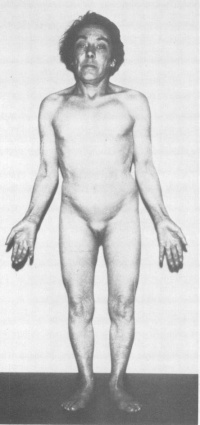

The most frequent clinical feature is short stature and gonadal dysgenesis. Other features may include coarctation of the aorta, renal anomalies, neck webbing, and lymphoedema. The affected organ systems and tissues may are effected to a lesser or greater extent amongst that are affected by turner syndrome. Each person who has turner syndrome all vary in their clinical phenotype. In recent years there has been increased interest in Turner Syndrome due to the introduction of growth hormone treatment. There has been marked improvement in the understanding of this condition as advances in molecular genetic techniques occur. However, there still further research to be completed. A multidisciplinary approach to treatment is important to improve the quality of life of girls with Turner Syndrome [3].

Epidemiology

Turner Syndrome affects about 1 in 2000 live-born females. There are three types of karyotypic abnormalities but the most frequently seen is where the entire X chromosome is missing resulting in 45 X karyotype. The remaining third have structural abnormalities of the X chromosomes, and two thirds are mosaics. Whereby, the maternal X is retained in two-thirds of women and the paternal X in the remainder. The phenotype of Turner Syndrome is varies but it involves anomalies of the sex chromosome. It could be caused by the limited amount of genetic material in these abnormal chromosomes. Turner Syndrome can be transmitted from mother to daughter, and thus can it could be described as a heredity linked syndrome [4].

The loss of one of the sex chromosomes of turner syndrome occurs after the zygote has formed or just after the fusion of the gametes. In 70-80% of cases the retained X is from the mother. In such circumstances has lead to the different phenotypic expression of the genes present on the X chromosome depending upon if it came from the mother or father. The morphological differences from those retaining the maternal compared to retaining the paternal X is have shown to have a greater incidence of cardiovascular anomalies and neck webbing. The missing sex chromosome could be either an X or a Y. This has clinical implications because if the Y material is present there is a risk of up to 30% of gonadoblastoma developing in the dysgenetic gonads. This is because the 'gonadoblastoma locus' is on the Y chromosome which is believed to be situated on the long arm of the Y just below the centromere. Another factor affecting the phenotype in Turner syndrome is the inactivation of the abnormal X chromosomes. In a normal fetus there should be only one X chromosome that is active in each cell [5]

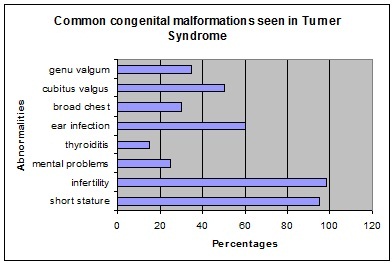

Abnormalities associated with Turner Syndrome [6].

Etiology

Causation of Turner Syndrome (TS) can be traced back to the stages of sex-cell development. When sex cells divide through a process called meiosis to create gametes, either a haploid egg (for females) or sperm (for males) two divisions occur, Meiosis I and Meiosis II. Meiosis is the main process which helps create the vast genetic diversity within all populations by allowing recombination and random assortment. During Meiosis I homologous chromosomes are separated; following Meiosis I, sister chromatids separate during Meiosis II. If during either stage of Meiosis I or II the homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids, respectively, do not fully separate, a phenomenon can occur called nondisjunction. Nondisjunction causes an uneven distribution of genetic material to each daughter nuclei. When an uneven distribution is such that one of the gametes does not have any of a chromosome, it can combine with another normal gamete to create a fertilized egg with only one chromosome as opposed to the normal two that are found in human cells; this is called a monosomy. When this occurs in the sex chromosomes leaving only a single X chromosome (X0 genotype) Turner Syndrome is created. Turner Syndrome can also be created by partial monosomy or disjunctions, meaning that although a whole X chromosome is not missing, portions of it are not present or are non-functional, rendering the chromosome useless. Any disjunction seems to be completely sporadic and have yet to be attributed to any genetic link. The only thing known for sure is that during conception a portion of or the whole second sex chromosome is not conveyed to the zygote.[7] Because at least one X chromosome is necessary for vital functions, this condition can only be found in females.

Turner Syndrome has also been linked to an increased risk of diabetes mellitus [8]

Clinical manifestations

Turner syndrome is associated with a cognitive phenotype. This includes a low IQ score, nonverbal learning disability, visuoperception deficit and attention deficity disorder. Problems with nonverbal learning involve the difficulty in mathematics. When calculating they are slow. Difficulty in both visuoperception and visuo-constructional tasks is observed when identifying and locating becomes difficult due to poor visual working memory. One other contributing factor to this is the delay in selecting visuospatial tasks. The incidence rate of attention skills and impulsivity in girls with turner syndrome is higher then children in the general population with ADHD [9].

Diagnostic Procedures

Diagnostic Definition

Turner syndrome is diagnosed through both an evaluation of physical features and by analysis of the second sex chromosome. The two criteria must be met for classification of Turner syndrome, an abnormality in the second sex chromosome must be found and the abnormality must be found to be expressed somehow in the individual's traits. Hence if physical characteristics are not present even when the cytogenetic criterion is met the patient is not diagnosed as having Turner syndrome.[10] In Turner syndrome the second sex chromosome is either:

- Completely absent (45,X)[11][12]

- Partially absent[13][14]

- Forms an isochromosome (isoXq), possessing a long arm duplication (q) and being devoid of a short arm (p)[15]

- In a ring formation (rX)[16][17]

- Is devoid of the homeobox gene, SHOX (short stature homeobox), the deletion being prior to the junction between Xp22.2 and Xp22.3[18][19]

Any of these variations of the second sex chromosome may occur with or without cell line mosaicism. Turner syndrome may be diagnosed prenatally or postnatally, using this genetic diagnostic definition coupled with an appropriate phenotypic evaluation of the individual, as outlined below.[20]

Prenatal Diagnosis

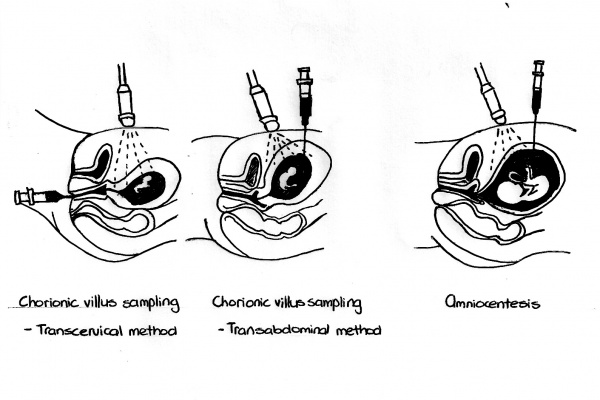

The prenatal diagnostic tool for Turner syndrome is karyotype screening and testing for phenotype abnormalities. If Turner syndrome is diagnosed prenatally, karyotype screening and an evaluation of the individual's traits should be conducted again postnatally for confirmation of this diagnosis. Turner syndrome is frequently diagnosed after karyotype screening during chorionic villous sampling or amniocentesis.[21] The table below outlines various prenatal tests conducted and the indications that may be present in babies with Turner syndrome. Although these techniques and the indications they reveal may highlight Turner syndrome signs, they should not be used as sole diagnostic tools.[22]

| Technique | Turner syndrome indications | Image |

| Ultrasound |

|

|

| Maternal serum screening |

|

Postnatal Diagnosis

In postnatal diagnosis, karyotype investigation is undertaken for the individual. When a female presents with the following clinical findings, explained in table below, it is recommended that chromosomal analysis is undertaken, so that Turner syndrome may be eliminated[36]:

| Age | Phenotypic manifestations/indications | Image |

| Baby/infant | ||

| Child |

|

|

| Adolescent/Adult |

Since an absence of the physical signs of puberty and/or growth failure are often seen as normal variations in the population, these possible indications/symptoms of Turner syndrome may not be further investigated by many clinicians.[61] When karyotyping in order to exclude natural cell variation, a sufficient number of cells should be assessed. Whilst a sample of blood will often reveal Turner syndrome, an evaluation of a second tissue sample like the skin is recommend.[62]

DNA hybridisation or fluorescent in situ hybridisation should be conducted using a Y centromeric or short arm probe to detect for any additional Y or X chromosomal material.

If there is any of the Y chromosome present, this may initiate gonadoblastoma development, another primary indicator of Turner syndrome. Hence the individual should have both a vaginal ultrasonograph and colour Doppler sonograph of their gonads to detect whether any Y chromosome fragments are present. These tests should be repeated regularly to monitor the patient for any malignancy, if a gonadectomy is not undertaken.[63][64]

Treatment

The most common abnormality is short stature as bone age is delaged due to the lack of estrogen. This could be treated with the completion of growth hormone therapy.

For young girls use a low dose of natural estrogen to promote and maintain secondary sex characteristics. However recommended to be used when she is approaching puberty in terms of social circumstances as physical sex appearance becomes apparent among her peers [65].

Evaluation and Management for Turner Syndrome

| MANAGEMENT | METHOD | FEATURE |

| Orthopedic evaluation | Physical examination | Congential hip dislocation |

| Cardiac evaluation and management | Echocardiogram | BAV or COA |

| renal anatomy evaluation | Renal ultrasound | Rotational abnormalities |

| Blood pressure | Physical examination | Hypertension |

| Speech | Speech therapist | Hypertension |

| Speech | Speech therapist | Speech loss |

| Inner ear | Therapist | Hearing loss |

| Outer ear | Observation | Malformation of the outer ear |

| Middle ear | Ventilation tubes | Otitis media |

| Thyroid function | Levels of TSH | Primary hypothyroidism |

| Hearing | Karyotyping | Hearing problems |

| Plastic surgery | Elective surgery | Keloid |

| Vision | Physical examination | Ptosis |

| Orthodontic exam | Orthodontist | Dental abnormalities |

| Weight | Counselling | Obesity |

| Lyphedema | Therapy | Occur and recur at any age |

| Glucose intolerance | Growth promotion | Diabetes |

Research

Current research

Since there is no preventative or cure, currently research is being conducted mainly into the areas of symptoms, possible treatments and risks involved with Turner syndrome.

Growth hormone therapy: its affect on height, weight and stature.

- Growth hormone effect on body composition in Turner syndrome.(2011)[66]:

- Health-related quality of life of young adults with Turner syndrome following a long-term randomized controlled trial of recombinant human growth hormone.(2011)[67]:

- Growth hormone treatment for Turner syndrome in Australia reveals that younger age and increased dose interact to improve response.(2011)[68]:

- Growth hormone treatment before the age of 4 years prevents short stature in young girls with Turner syndrome.(2011)[69]:

Oestrogen hormone replacement therapy: the adequate dosage and its effect on uterine development, breast development, bone mineral density and sexual characteristics.

- Growth hormone plus childhood low-dose estrogen in Turner's syndrome.(2011)[70]:

- Estrogen requirements in girls with Turner syndrome; how low is enough for initiating puberty and uterine development?(2011)[71]:

- Puberty induction in Turner syndrome: results of oestrogen treatment on development of secondary sexual characteristics, uterine dimensions and serum hormone levels.(2009)[72]:

Risks

- Familial occurrence of Turner syndrome: casual event or increased risk?(2011)[73]: This research examined whether there is a higher probability of having a second child with Turner syndrome and concluded that there is evidence in the small cohort that they used of a greater probability. It is suggested that a larger study be conducted to look further into these findings.

- [74]

- [75]

Future research

Future research needs to be conducted in the following areas: to follow up on the suggestions given in the current research as outlined in the prior section and also into how the care system is functioning for Turner syndrome individuals as outlined below.

- Medical Care of Girls with Turner Syndrome: Where are we Lacking?(2011)[76]: This research found that a large proportion (>50%) of people with Turner syndrome are not given adequate information upon diagnosis or screenings for complications and symptoms. Therefore it is suggested in order to rectify this issue that more education should be given to physicians on the syndrome

- Turner's syndrome requires multidisciplinary approach.(2009)[77]: This article evaluates the need for a multidisciplinary approach to treatment of Turner syndrome. Since the symptoms can be wide ranging and severe, it is difficult but necessary for all of them to be examined in each individual. Hence a greater care plan for individuals should be implemented upon diagnosis.

Glossary

Alpha-fetoprotein is a protein with an unknown function. It makes up, up to one third of the protein serum levels found in the second trimester of pregnancy and in neural tube defects, these alpha-fetoprotein levels are elevated. [78]

Amniocentesis is a prenatal diagnostic tool. The procedure involves the sampling of amniotic fluid from the amniotic sac using a syringe, that is then tested for a number of abnormalities. [79]

Brachycephaly is a condition where the coronal suture of the skull fuses prematurely. Since the skull is unable to expand any further in the anterior-posterior directions due to this closure, it grows to an abnormal size in in the lateral dimension.[80]

Coarctation of the aorta is an abnormality where the aorta is constricted at one or various sections. This can be caused by genetic and/or environmental factors.[81]

Chorionic villous sampling is a prenatal diagnostic tool which can be used from 7 weeks after fertilisation. It is used to test for a number of chromosomal abnormalities including X-linked and metabolic disorders.[82]

Cubitus valgus is where an individual's elbows are turned in.

Cystic hygroma is a prenatal abnormality where fluid builds up in the posterior portion of the neck. The body may or may not relieve itself naturally of this accumulation of fluid after birth. [83]

DNA-DNA hybridisation is a technique used to compare the similarities and differences between two sets of genes.[84]

Doppler sonography uses the doppler effect to help image and measure blood flow pattern in the patient.[85]

Estriol is a hormone that is produced in greater amounts during pregnancy especially in the second and third trimester. One of its main functions is to assist with blood flow in the placenta and uterus.[86]

Gametes are reproductive cells (specifically eggs and sperm) that can unite to form a new cell called a zygote.

Gonadoblastoma is an abnormal proliferation of gonadal cells, that may or may not be malignant.[87]

Haploid is the status of a cell having only a single set of unpaired chromosomes.

hCG is the abbreviation for human chorionic gonadotropin. It is a hormone that functions in the early stage of pregnancy to maintain the blood supply to the corpus luteum.[88]

Homologous chromosomes

Hypoplasia is when an organ or tissue is not completely developed.[89]

Inhibin A is a peptide produced by the ovaries and acts to restrain the production of follicle-stimulating hormone.[90]

Karyotype is an individual's set of chromosomes, both their number and appearance.[91]

Meiosis is the process of cell division within sex cells which halves the number of chromosomes in the cells, creating haploid gametes (sex cells) from diploid cells.

Monosomy the condition of a chromosome having no homologue, or matching chromosome to pair with

Mosaicism is when a particular type or all cells of an individual do not have the same genetic makeup. This is caused by a mutation during embryonic cell division.[92]

Nondisjunction is the failure of chromosome pairs to separate entirely during either stage of Meiosis

Oligohydramnios is a prenatal condition, where there is an insufficient amount of amniotic fluid.[93]

Polyhydramnios is a prenatal condition, where there is an excessive amount of amniotic fluid.[94]

Random assortment

Recombination is the process which by genetic material is crossed over and switched between two segments of DNA which adds to the genetic diversity of the genome.

SHOX gene is the short stature homeobox gene, that when deficient frequently results in short stature.[95]

Sister chromatids

Ultrasonography is a medical technique that employs ultrasound frequencies to visualise a patient's internal bodily structure.[96]

References

- ↑ Turner HH (1938). "A syndrome of infantilism, congenital webbed neck, and cubitus valgus". Endocrinology 23: 566–74. doi:10.1210/endo-23-5-566

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1273980/?log$=activity

- ↑ http://eje-online.org/content/151/6/657.long

- ↑ http://eje-online.org/content/151/6/657.long

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (2009-09-15). "New Clues to Sex Anomalies in How Y Chromosomes Are Copied". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-26. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1511250/?page=2

- ↑ http://eje-online.org/content/151/6/657.long

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/15/science/15chrom.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1&hpw

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC2741724</pubmed>

- ↑ http://jcem.endojournals.org/content/84/12/4345.long

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1511250</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1511250</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1511250</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21325865</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21527014</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21527014</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16544046</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16544046</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10599686</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16544046</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6753342</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6753342</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21527014</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6753342</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6753342</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6753342</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6753342</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21527014</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6753342</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21527014</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20361125</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>1511250</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16714725</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1273980/?page=3

- ↑ <pubmed>21720878</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21619701</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21375553</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21398400</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21449786</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21793702</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19200215</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21648298</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed></pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed></pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>21454226</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>19514616</pubmed>

- ↑ McPherson, R 2011, McPherson: Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods, 22nd ed., ebook, accessed 15 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?about=true&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4377-0974-2..C2009-0-45915-4--TOP&isbn=978-1-4377-0974-2&uniqId=282556246-14

- ↑ Moore, K & Persaud, T 2007, Moore & Persaud: Before We Are Born, 7th ed., ebook, accessed 15 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-3705-7..X5001-3--TOP&isbn=978-1-4160-3705-7&about=true&uniqId=282556246-15

- ↑ Flint, P 2010, Flint: Cummings Otolaryngology: Head & Neck Surgery, 5th ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?about=true&eid=4-u1.0-B978-0-323-05283-2..00186-5--s0045&isbn=978-0-323-05283-2&uniqId=282726024-5

- ↑ Moore, K & Persaud, T 2007, Moore & Persaud: Before We Are Born, 7th ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-3705-7..X5001-3--TOP&isbn=978-1-4160-3705-7&about=true&uniqId=282556246-15

- ↑ Moore, K & Persaud, T 2007, Moore & Persaud: Before We Are Born, 7th ed., ebook, accessed 15 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-3705-7..X5001-3--TOP&isbn=978-1-4160-3705-7&about=true&uniqId=282556246-15

- ↑ Gabbe, S 2007, Gabbe: Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 5th ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?about=true&eid=4-u1.0-B978-0-443-06930-7..50011-6--cesec51&isbn=978-0-443-06930-7&uniqId=282726024-10

- ↑ Long, S 2009, Bradley: Neurology in Clinical Practice, 5th ed.Long: Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases Revised Reprint, 3rd ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/page.do?eid=4-u1.0-B978-0-7020-3468-8..C2009-0-41479-X&isbn=978-0-7020-3468-8&uniqId=282726024-19#4-u1.0-B978-0-7020-3468-8..C2009-0-41479-X--TOP

- ↑ Bradley, W 2008, Bradley: Neurology in Clinical Practice, 5th ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/page.do?eid=4-u1.0-B978-0-7506-7525-3..X5001-8&isbn=978-0-7506-7525-3&uniqId=282726024-17#4-u1.0-B978-0-7506-7525-3..X5001-8--TOP

- ↑ McPherson, R 2011, McPherson: Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods, 22nd ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?about=true&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4377-0974-2..C2009-0-45915-4--TOP&isbn=978-1-4377-0974-2&uniqId=282556246-14

- ↑ Wein, A 2011, Wein: Campbell-Walsh Urology, 10th. ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?about=true&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-6911-9..00156-0--s0040&isbn=978-1-4160-6911-9&uniqId=282726024-29

- ↑ McPherson, R 2011, McPherson: Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods, 22nd ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?about=true&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4377-0974-2..C2009-0-45915-4--TOP&isbn=978-1-4377-0974-2&uniqId=282556246-14

- ↑ Wein, A 2011, Wein: Campbell-Walsh Urology, 10th. ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?about=true&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-6911-9..00156-0--s0040&isbn=978-1-4160-6911-9&uniqId=282726024-29

- ↑ Melmed, S 2011, Melmed: Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, 12th ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?about=true&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4377-0324-5..00045-6&isbn=978-1-4377-0324-5&uniqId=282726024-25

- ↑ McPherson, R 2011, McPherson: Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods, 22nd ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?about=true&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4377-0974-2..C2009-0-45915-4--TOP&isbn=978-1-4377-0974-2&uniqId=282556246-14

- ↑ <pubmed>11443168</pubmed>

- ↑ Moore, K & Persaud, T 2007, Moore & Persaud: Before We Are Born, 7th ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-3705-7..X5001-3--TOP&isbn=978-1-4160-3705-7&about=true&uniqId=282556246-15

- ↑ Moore, K & Persaud, T 2007, Moore & Persaud: Before We Are Born, 7th ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/about.do?eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-3705-7..X5001-3--TOP&isbn=978-1-4160-3705-7&about=true&uniqId=282556246-15

- ↑ <pubmed>21325865</pubmed>

- ↑ Bradley, W 2008, Bradley: Neurology in Clinical Practice, 5th ed., ebook, accessed 20 September 2011 from MD Consult Australia, http://www.mdconsult.com/books/page.do?eid=4-u1.0-B978-0-7506-7525-3..X5001-8&isbn=978-0-7506-7525-3&uniqId=282726024-17#4-u1.0-B978-0-7506-7525-3..X5001-8--TOP

2011 Projects: Turner Syndrome | DiGeorge Syndrome | Klinefelter's Syndrome | Huntington's Disease | Fragile X Syndrome | Tetralogy of Fallot | Angelman Syndrome | Friedreich's Ataxia | Williams-Beuren Syndrome | Duchenne Muscular Dystrolphy | Cleft Palate and Lip