1987 Developmental Stages In Human Embryos - Stage 19

| Embryology - 25 Apr 2024 |

|---|

| Google Translate - select your language from the list shown below (this will open a new external page) |

|

العربية | català | 中文 | 中國傳統的 | français | Deutsche | עִברִית | हिंदी | bahasa Indonesia | italiano | 日本語 | 한국어 | မြန်မာ | Pilipino | Polskie | português | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਦੇ | Română | русский | Español | Swahili | Svensk | ไทย | Türkçe | اردو | ייִדיש | Tiếng Việt These external translations are automated and may not be accurate. (More? About Translations) |

O'Rahilly R. and Müller F. Developmental Stages in Human Embryos. Contrib. Embryol., Carnegie Inst. Wash. 637 (1987).

| Online Editor Note |

|---|

| O'Rahilly R. and Müller F. Developmental Stages in Human Embryos. Contrib. Embryol., Carnegie Inst. Wash. 637 (1987).

The original 1987 publication text, figures and tables have been altered in formatting, addition of internal online links, and links to PubMed. Original Document - Copyright © 1987 Carnegie Institution of Washington.

|

- 1987 Stages: Introduction | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | References | Appendix 1 | Appendix 2 | Historic Papers | Embryonic Development

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Introduction To Stages 19-23

As the embryo advances into more-specialized levels, it becomes necessary to take into account the developmental status of various internal structures in order to assign the specimen precisely to a stage.

| For stages 19–23, Streeter devised a system of rating the development of selected structures by “point scores.” The eight features chosen were the cornea, optic nerve, cochlear duct, adenohypophysis, vomeronasal organ, submandibular gland, metanephros, and humerus. He regarded these as arbitrarily selected key structures that were readily recognizable under the microscope and that could be recorded by camera lucida sketches from serial sections.

|

Table 19-1. Number of Developmental Points per Embryo

|

A detailed table showing the assignment of scoring points is available in Streeter’s work (1951, pp. 170 and 171) but is not reproduced here because of the considerable technical difficulty that would be involved in repeating Streeter’s successful but rather personal procedure in a consistent manner. Moreover, some slight problems exist in the arrangement of the table, as it was printed. These may have been caused by the circumstance that the final version had to be prepared by others, namely Heuser and Corner.

It is to be stressed that considerable caution needs to be exercised in assigning a given embryo to stages 19–23, particularly in the absence of detailed studies of its internal structure. The external form of a new embryo should be compared in detail with Streeter’s photographs (figs. 19-1, 20-1, etc.). The greatest length of the embryo should also be taken into account.

Stage 19 is not quite as difficult as the later stages to identify, because toe rays are prominent but interdigital notches have not yet appeared. The foot is still an important guide in later stages but difficulties may well be encountered in stages 20–22, such that it is frequently more prudent to conclude with a weak designation such as “approximately stage 20” or “stage 20–21” or “probably stage 22.” Stage 23, at least at its full expression, is again less difficult to identify because of its more mature appearance. In addition, certain internal features, such as the status of the skeleton, are important guides for stages 19–23.

Some embryos from other laboratories have unfortunately been recorded in the literature as belonging to various specific stages without sufficiently detailed and careful examination of their structural features.

Stage 19

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

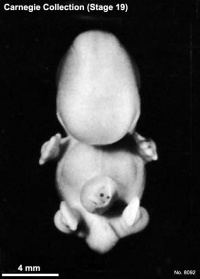

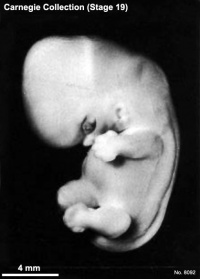

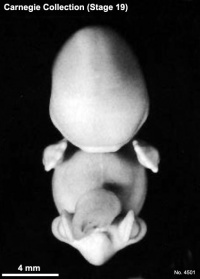

Fig. 19-1. Photographs of three embryos belonging to stage 19. The trunk is now beginning to straighten, and the cervical angulation is less acute. The coalescence of parts in the pharyngeal region has altered the appearance of the auricle, and the hillocks are less conspicuous. The longitudinal axes of the upper limbs are almost at a right angle to the dorsal contour of the body of the embryo, and the axes of the upper and lower limbs are more or less parallel, so that each limb has a pre-axial and a postaxial border. The transverse and sigmoid sinuses are prominent in D. The brain in E shows, from above downward, the mesencephalon, diencephalon, and cerebral hemispheres. Top row, No. 8092. Middle row, No. 6824. Bottom row, No. 4501. All limbs are at the same magnification.

Size and Age

Most embryos of this stage measure 17–20 mm in length.

The age is believed to be approximately 47–48 postovulatory days. One embryo (No. 1390) is known to be “exactly 47 days” (Mall, 1918), although another appears to have been only 41 days (Moore, Hutchins, and O’Rahilly, 1981).

External Form

The trunk has begun to elongate and straighten slightly, with the result that the head no longer forms a right angle with the line of the back of the embryo. The limbs extend nearly directly forward. The toe rays are more prominent, but interdigital notches have not yet appeared in the rim of the foot plate.

Features For Point Scores

- Cornea. A thin layer of mesenchyme crosses the summit of the cornea (Streeter, 1951, fig. 14). General views of the eye at stages 13–23 are shown in figures 19-2 and 19-3, and at stages 19–23 in figure 19-5.

- Optic nerve. The optic nerve is slender (fig. 19-4). Nerve fibers can be traced for a short distance beyond the retina but have not yet reached the middle region of the stalk.

- Cochlear duct. The tip of the L-shaped cochlear duct turns “upward” (fig. 19-6).

- Adenohypophysis. The pars intermedia is beginning to be established, as well as the lateral lobes that will form the pars tuberalis (fig. 19-7). The stalk is relatively thick and contains the remains of the lumen of the hypophysial sac. Transverse views of the gland at stages 19–23 are shown in figure 19-8.

- Vomeronasal organ. The vomeronasal organ is a thickening of the nasal epithelium that still bounds a shallow groove or pit (fig. 19-9).

- Submandibular gland. The primordium of the submandibular gland is present in stage 18 as an epithelial thickening in the groove between the tongue and the future lower jaw. In stage 19, an area of condensed mesenchyme appears beneath the duct (fig. 19-10 and Streeter, 1951, fig. 24).

- Metanephros. In many areas the metanephrogenic tissue around the ampullae of the collecting tubules remains undifferentiated but, in others, nodules become separated from the metanephrogenic mantle (fig. 19-11). In some of these, small cavities have appeared, transforming them into renal vesicles.

- Humerus. Differentiation of chondrocytes had already progressed to phase 3 by stage 18, and phases 1–3 continue to be present in stages 19 and 20 (Streeter, 1949, fig. 3 and plate 2). The middle of the shaft is becoming clearer. Although no sign is present in the humerus, ossification begins in the clavicle and mandible in one of the stages from 18 to 20, and in the maxilla at stage 19 or stage 20 (O’Rahilly and Gardner, 1972)[1].

Additional Features

- Blood vascular system. The arterial system has been depicted by Evans in Keibel and Mall (1912, fig. 447). Excellent views of reconstructions of the aortic arches at stages 11–19 were published by Congdon (1922, figs. 29–40).

- Heart. The ventricles are situated ventral to the atria, so that a horizontal section corresponds approximately to a coronal section of the adult organ. Such a section has been reproduced by Cooper and O’Rahilly (1971, fig. 1), who also provided an account of several features of the heart at stages 19–21. Fusion of the aortic and mitral endocardial cushion material occurs at stage 19 (Teal, Moore, and Hutchins, 1986).

- Lungs. The bronchial tree was reconstructed by Wells and Boyden (1954, plates 3 and 4). The first generation of subsegmental bronchi is now complete.

- Cloacal region. The cloacal membrane ruptures from urinary pressure at stage 18 or stage 19, and the anal membrane becomes defined.

- Gonads. The rete testis develops from the seminiferous cords at stages 19–23, and the tunica albuginea forms (Jirasek, 1971). Cords representing the rete ovarii are also developing (Wilson, 1926a).

- Sternum. Right and left sternal bars, which are joined cranially to form the episternal cartilage, are present by stage 19 (Gasser, 1975, figs. 7-17 and 7-22).

- Brain A general view of the organ was given by Gilbert (1987, fig. 18), and certain internal details were provided by Hines (1922, figs. 15 and 16). In the rhombencephalon the migration for the formation of the olivary and arcuate nuclei has begun. In most embryos the choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle is now present. In median sections the paraphysis marks the limit between diencephalic and telencephalic roof. A characteristic wedge appearance of the "anterior lobe" of the epiphysis is found (O'Rahilly, 1968). The stria medullaris thalami reaches the habenular nuclei. The habenular commissure may begin to develop. Half of the length of the cerebral hemispheres reaches further rostrally than the lamina terminalis, and half of the diencephalon is covered by them. The occipital pole of the hemisphere can be distinguished caudally and ventrolaterally. The internal capsule begins to develop.

Embryo of Stage 19 Already Described

Harvard No. 839, 17.8 mm G.L. Described and illustrated in monographic form by Thyng (1914).[2]

References

| Online Editor Note |

|---|

| O'Rahilly R. and Müller F. Developmental Stages in Human Embryos. Contrib. Embryol., Carnegie Inst. Wash. 637 (1987).

The original 1987 publication text, figures and tables have been altered in formatting, addition of internal online links, and links to PubMed. Original Document - Copyright © 1987 Carnegie Institution of Washington.

|

- ↑ <pubmed>5042780</pubmed>

- ↑ Thyng FW. The anatomy of a 17.8 mm human embryo. (1914) Amer. J Anat. 17: 31-112.

See also <pubmed>2268071</pubmed>

Search Pubmed

- 1987 Stages: Introduction | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | References | Appendix 1 | Appendix 2 | Historic Papers | Embryonic Development

| Historic Disclaimer - information about historic embryology pages |

|---|

| Pages where the terms "Historic" (textbooks, papers, people, recommendations) appear on this site, and sections within pages where this disclaimer appears, indicate that the content and scientific understanding are specific to the time of publication. This means that while some scientific descriptions are still accurate, the terminology and interpretation of the developmental mechanisms reflect the understanding at the time of original publication and those of the preceding periods, these terms, interpretations and recommendations may not reflect our current scientific understanding. (More? Embryology History | Historic Embryology Papers) |

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 25) Embryology 1987 Developmental Stages In Human Embryos - Stage 19. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/1987_Developmental_Stages_In_Human_Embryos_-_Stage_19

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G