File:Meyer1932history2 fig02.jpg

Original file (628 × 800 pixels, file size: 130 KB, MIME type: image/jpeg)

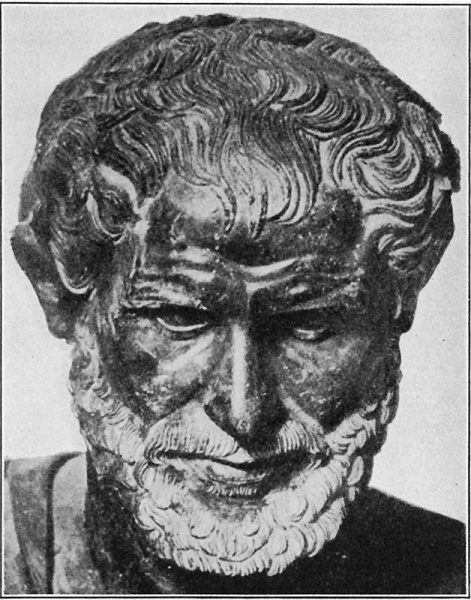

Fig. 2. Aristotle

From Herculaneum. Probably work of fourth century B. C.

The illustrations of Aristotle and Hippocrates are from Singer, Greek Biology and Greek Medicine. (British Museum, second or third century B. C.)

Some of the observations and reflections of Aristotle upon the procreation and development of animals which are a continuation of those in the Hippocratic writings exerted a great influence on embryology up to the seventeenth century because of the authority of his great name. Indeed, some of the misconceptions found in Aristotle are still current today in other than lay circles. Aristotle, the master of them that know, as Dante called him, himself examined incubating eggs and his idea of equivocal or spontaneous generation of eels, some species of fish. insects. and worms, remained current regarding some forms of life until overthrown by the convincing experiments of Pasteur. Aristotle suggested four methods of the origin of life and believed that the organic could arise from the inorganic and also from heat. Since the ancients believed that the inorganic also had a soul, such a conception of spontaneous generation should not surprise us. Nor should we marvel that Aristotle believed in the occurrence of parthenogenesis in higher forms of life. He could not detect the two sexes in all forms of animal life.

Aristotle regarded menstrual blood, in a sense, as the equivalent of ,semen, and held that menstruation in women is comparable to estrus or heat in mammals, an error still found in contemporary literature. He also held that the menstrual flow is comparable to the eggs of other animals, and that eggs form only through the influence of the male, the female supplying the substance and the male the energizing power. somewhat as we of today still use the word “fertilization” and incorrectly regard the spermatozoon as merely supplying a ferment to the ovum to inaugurate cell division. It is true that parthenogenetic development can be started artificially in some ova by chemical means as Loeb showed for the sea urchin, or by spermatic extract which presumably also is chemical. as Lillie discovered. This has not been possible in regard to the sperm but the two cells play an equivalent role in heredity.

To Aristotle the catamenia were imperfect semen which contained no soul because the male contributed the immaterial or controlling force. This idea was held also by Harvey, who believed, after Aristotle, that the cock contributes no substance but only an influence which makes the egg perfect and so initiates development. Aristotle carried this idea so far as to hold that the female partridge could be fertilized by the breath of the male, but it is not always easy to tell whether Aristotle is speaking upon the basis of observations or hearsay, as when he says that SCOI'pl0I1S are born alive after the union of male and female. Anyone interested in Aristotle and Hippocrates will enjoy the essay by Singer.

Since the mode of reproduction of eels was not described till 1896 it is no wonder that Aristotle thought they had no generative organs. He never could find milt or roe and so concluded that eels arose from the entrails of the earth like certain worms. Aristotle was familiar with hermaphroditism in bees and with the occurrence of viviparous fishes. He knew the vitelline and allantoic vessels and the accompanying sacs and studied a twelve-day chick. He also knew something about the fate of the allantois and the yolk sac.

Since the medical school at Alexandria was known throughout the world for its enterprise in dissection of the dead, it seems as though the great men active there, such as Herophilus and Erasistratos, must also have made observations on embryology. There is no record of this, however, and one is left to pure surmise regarding this matter as regarding other things. The Alexandrians were supposed to have dissected the bodies of living men, but it has never been established that they did so. It does not seem unlikely, however, that some criminal might have been willing to take a chance on surviving an inspection of some part of his body under the knife of anatomists rather than suffer a cruel death after torture, and we must remember that dissection in that day meant something wholly different than now.

Reference

Meyer AW. Essays on the History of Embryology: Part II. Cal West Med. 1932 Jan;36(1):40-4. PMID 18742009

Cite this page: Hill, M.A. (2024, April 19) Embryology Meyer1932history2 fig02.jpg. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/File:Meyer1932history2_fig02.jpg

- © Dr Mark Hill 2024, UNSW Embryology ISBN: 978 0 7334 2609 4 - UNSW CRICOS Provider Code No. 00098G

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 17:03, 2 November 2015 |  | 628 × 800 (130 KB) | Z8600021 (talk | contribs) | |

| 17:02, 2 November 2015 |  | 800 × 1,096 (222 KB) | Z8600021 (talk | contribs) |

You cannot overwrite this file.

File usage

The following 3 pages use this file: